- •Preface

- •Imaging Microscopic Features

- •Measuring the Crystal Structure

- •References

- •Contents

- •1.4 Simulating the Effects of Elastic Scattering: Monte Carlo Calculations

- •What Are the Main Features of the Beam Electron Interaction Volume?

- •How Does the Interaction Volume Change with Composition?

- •How Does the Interaction Volume Change with Incident Beam Energy?

- •How Does the Interaction Volume Change with Specimen Tilt?

- •1.5 A Range Equation To Estimate the Size of the Interaction Volume

- •References

- •2: Backscattered Electrons

- •2.1 Origin

- •2.2.1 BSE Response to Specimen Composition (η vs. Atomic Number, Z)

- •SEM Image Contrast with BSE: “Atomic Number Contrast”

- •SEM Image Contrast: “BSE Topographic Contrast—Number Effects”

- •2.2.3 Angular Distribution of Backscattering

- •Beam Incident at an Acute Angle to the Specimen Surface (Specimen Tilt > 0°)

- •SEM Image Contrast: “BSE Topographic Contrast—Trajectory Effects”

- •2.2.4 Spatial Distribution of Backscattering

- •Depth Distribution of Backscattering

- •Radial Distribution of Backscattered Electrons

- •2.3 Summary

- •References

- •3: Secondary Electrons

- •3.1 Origin

- •3.2 Energy Distribution

- •3.3 Escape Depth of Secondary Electrons

- •3.8 Spatial Characteristics of Secondary Electrons

- •References

- •4: X-Rays

- •4.1 Overview

- •4.2 Characteristic X-Rays

- •4.2.1 Origin

- •4.2.2 Fluorescence Yield

- •4.2.3 X-Ray Families

- •4.2.4 X-Ray Nomenclature

- •4.2.6 Characteristic X-Ray Intensity

- •Isolated Atoms

- •X-Ray Production in Thin Foils

- •X-Ray Intensity Emitted from Thick, Solid Specimens

- •4.3 X-Ray Continuum (bremsstrahlung)

- •4.3.1 X-Ray Continuum Intensity

- •4.3.3 Range of X-ray Production

- •4.4 X-Ray Absorption

- •4.5 X-Ray Fluorescence

- •References

- •5.1 Electron Beam Parameters

- •5.2 Electron Optical Parameters

- •5.2.1 Beam Energy

- •Landing Energy

- •5.2.2 Beam Diameter

- •5.2.3 Beam Current

- •5.2.4 Beam Current Density

- •5.2.5 Beam Convergence Angle, α

- •5.2.6 Beam Solid Angle

- •5.2.7 Electron Optical Brightness, β

- •Brightness Equation

- •5.2.8 Focus

- •Astigmatism

- •5.3 SEM Imaging Modes

- •5.3.1 High Depth-of-Field Mode

- •5.3.2 High-Current Mode

- •5.3.3 Resolution Mode

- •5.3.4 Low-Voltage Mode

- •5.4 Electron Detectors

- •5.4.1 Important Properties of BSE and SE for Detector Design and Operation

- •Abundance

- •Angular Distribution

- •Kinetic Energy Response

- •5.4.2 Detector Characteristics

- •Angular Measures for Electron Detectors

- •Elevation (Take-Off) Angle, ψ, and Azimuthal Angle, ζ

- •Solid Angle, Ω

- •Energy Response

- •Bandwidth

- •5.4.3 Common Types of Electron Detectors

- •Backscattered Electrons

- •Passive Detectors

- •Scintillation Detectors

- •Semiconductor BSE Detectors

- •5.4.4 Secondary Electron Detectors

- •Everhart–Thornley Detector

- •Through-the-Lens (TTL) Electron Detectors

- •TTL SE Detector

- •TTL BSE Detector

- •Measuring the DQE: BSE Semiconductor Detector

- •References

- •6: Image Formation

- •6.1 Image Construction by Scanning Action

- •6.2 Magnification

- •6.3 Making Dimensional Measurements With the SEM: How Big Is That Feature?

- •Using a Calibrated Structure in ImageJ-Fiji

- •6.4 Image Defects

- •6.4.1 Projection Distortion (Foreshortening)

- •6.4.2 Image Defocusing (Blurring)

- •6.5 Making Measurements on Surfaces With Arbitrary Topography: Stereomicroscopy

- •6.5.1 Qualitative Stereomicroscopy

- •Fixed beam, Specimen Position Altered

- •Fixed Specimen, Beam Incidence Angle Changed

- •6.5.2 Quantitative Stereomicroscopy

- •Measuring a Simple Vertical Displacement

- •References

- •7: SEM Image Interpretation

- •7.1 Information in SEM Images

- •7.2.2 Calculating Atomic Number Contrast

- •Establishing a Robust Light-Optical Analogy

- •Getting It Wrong: Breaking the Light-Optical Analogy of the Everhart–Thornley (Positive Bias) Detector

- •Deconstructing the SEM/E–T Image of Topography

- •SUM Mode (A + B)

- •DIFFERENCE Mode (A−B)

- •References

- •References

- •9: Image Defects

- •9.1 Charging

- •9.1.1 What Is Specimen Charging?

- •9.1.3 Techniques to Control Charging Artifacts (High Vacuum Instruments)

- •Observing Uncoated Specimens

- •Coating an Insulating Specimen for Charge Dissipation

- •Choosing the Coating for Imaging Morphology

- •9.2 Radiation Damage

- •9.3 Contamination

- •References

- •10: High Resolution Imaging

- •10.2 Instrumentation Considerations

- •10.4.1 SE Range Effects Produce Bright Edges (Isolated Edges)

- •10.4.4 Too Much of a Good Thing: The Bright Edge Effect Hinders Locating the True Position of an Edge for Critical Dimension Metrology

- •10.5.1 Beam Energy Strategies

- •Low Beam Energy Strategy

- •High Beam Energy Strategy

- •Making More SE1: Apply a Thin High-δ Metal Coating

- •Making Fewer BSEs, SE2, and SE3 by Eliminating Bulk Scattering From the Substrate

- •10.6 Factors That Hinder Achieving High Resolution

- •10.6.2 Pathological Specimen Behavior

- •Contamination

- •Instabilities

- •References

- •11: Low Beam Energy SEM

- •11.3 Selecting the Beam Energy to Control the Spatial Sampling of Imaging Signals

- •11.3.1 Low Beam Energy for High Lateral Resolution SEM

- •11.3.2 Low Beam Energy for High Depth Resolution SEM

- •11.3.3 Extremely Low Beam Energy Imaging

- •References

- •12.1.1 Stable Electron Source Operation

- •12.1.2 Maintaining Beam Integrity

- •12.1.4 Minimizing Contamination

- •12.3.1 Control of Specimen Charging

- •12.5 VPSEM Image Resolution

- •References

- •13: ImageJ and Fiji

- •13.1 The ImageJ Universe

- •13.2 Fiji

- •13.3 Plugins

- •13.4 Where to Learn More

- •References

- •14: SEM Imaging Checklist

- •14.1.1 Conducting or Semiconducting Specimens

- •14.1.2 Insulating Specimens

- •14.2 Electron Signals Available

- •14.2.1 Beam Electron Range

- •14.2.2 Backscattered Electrons

- •14.2.3 Secondary Electrons

- •14.3 Selecting the Electron Detector

- •14.3.2 Backscattered Electron Detectors

- •14.3.3 “Through-the-Lens” Detectors

- •14.4 Selecting the Beam Energy for SEM Imaging

- •14.4.4 High Resolution SEM Imaging

- •Strategy 1

- •Strategy 2

- •14.5 Selecting the Beam Current

- •14.5.1 High Resolution Imaging

- •14.5.2 Low Contrast Features Require High Beam Current and/or Long Frame Time to Establish Visibility

- •14.6 Image Presentation

- •14.6.1 “Live” Display Adjustments

- •14.6.2 Post-Collection Processing

- •14.7 Image Interpretation

- •14.7.1 Observer’s Point of View

- •14.7.3 Contrast Encoding

- •14.8.1 VPSEM Advantages

- •14.8.2 VPSEM Disadvantages

- •15: SEM Case Studies

- •15.1 Case Study: How High Is That Feature Relative to Another?

- •15.2 Revealing Shallow Surface Relief

- •16.1.2 Minor Artifacts: The Si-Escape Peak

- •16.1.3 Minor Artifacts: Coincidence Peaks

- •16.1.4 Minor Artifacts: Si Absorption Edge and Si Internal Fluorescence Peak

- •16.2 “Best Practices” for Electron-Excited EDS Operation

- •16.2.1 Operation of the EDS System

- •Choosing the EDS Time Constant (Resolution and Throughput)

- •Choosing the Solid Angle of the EDS

- •Selecting a Beam Current for an Acceptable Level of System Dead-Time

- •16.3.1 Detector Geometry

- •16.3.2 Process Time

- •16.3.3 Optimal Working Distance

- •16.3.4 Detector Orientation

- •16.3.5 Count Rate Linearity

- •16.3.6 Energy Calibration Linearity

- •16.3.7 Other Items

- •16.3.8 Setting Up a Quality Control Program

- •Using the QC Tools Within DTSA-II

- •Creating a QC Project

- •Linearity of Output Count Rate with Live-Time Dose

- •Resolution and Peak Position Stability with Count Rate

- •Solid Angle for Low X-ray Flux

- •Maximizing Throughput at Moderate Resolution

- •References

- •17: DTSA-II EDS Software

- •17.1 Getting Started With NIST DTSA-II

- •17.1.1 Motivation

- •17.1.2 Platform

- •17.1.3 Overview

- •17.1.4 Design

- •Simulation

- •Quantification

- •Experiment Design

- •Modeled Detectors (. Fig. 17.1)

- •Window Type (. Fig. 17.2)

- •The Optimal Working Distance (. Figs. 17.3 and 17.4)

- •Elevation Angle

- •Sample-to-Detector Distance

- •Detector Area

- •Crystal Thickness

- •Number of Channels, Energy Scale, and Zero Offset

- •Resolution at Mn Kα (Approximate)

- •Azimuthal Angle

- •Gold Layer, Aluminum Layer, Nickel Layer

- •Dead Layer

- •Zero Strobe Discriminator (. Figs. 17.7 and 17.8)

- •Material Editor Dialog (. Figs. 17.9, 17.10, 17.11, 17.12, 17.13, and 17.14)

- •17.2.1 Introduction

- •17.2.2 Monte Carlo Simulation

- •17.2.4 Optional Tables

- •References

- •18: Qualitative Elemental Analysis by Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectrometry

- •18.1 Quality Assurance Issues for Qualitative Analysis: EDS Calibration

- •18.2 Principles of Qualitative EDS Analysis

- •Exciting Characteristic X-Rays

- •Fluorescence Yield

- •X-ray Absorption

- •Si Escape Peak

- •Coincidence Peaks

- •18.3 Performing Manual Qualitative Analysis

- •Beam Energy

- •Choosing the EDS Resolution (Detector Time Constant)

- •Obtaining Adequate Counts

- •18.4.1 Employ the Available Software Tools

- •18.4.3 Lower Photon Energy Region

- •18.4.5 Checking Your Work

- •18.5 A Worked Example of Manual Peak Identification

- •References

- •19.1 What Is a k-ratio?

- •19.3 Sets of k-ratios

- •19.5 The Analytical Total

- •19.6 Normalization

- •19.7.1 Oxygen by Assumed Stoichiometry

- •19.7.3 Element by Difference

- •19.8 Ways of Reporting Composition

- •19.8.1 Mass Fraction

- •19.8.2 Atomic Fraction

- •19.8.3 Stoichiometry

- •19.8.4 Oxide Fractions

- •Example Calculations

- •19.9 The Accuracy of Quantitative Electron-Excited X-ray Microanalysis

- •19.9.1 Standards-Based k-ratio Protocol

- •19.9.2 “Standardless Analysis”

- •19.10 Appendix

- •19.10.1 The Need for Matrix Corrections To Achieve Quantitative Analysis

- •19.10.2 The Physical Origin of Matrix Effects

- •19.10.3 ZAF Factors in Microanalysis

- •X-ray Generation With Depth, φ(ρz)

- •X-ray Absorption Effect, A

- •X-ray Fluorescence, F

- •References

- •20.2 Instrumentation Requirements

- •20.2.1 Choosing the EDS Parameters

- •EDS Spectrum Channel Energy Width and Spectrum Energy Span

- •EDS Time Constant (Resolution and Throughput)

- •EDS Calibration

- •EDS Solid Angle

- •20.2.2 Choosing the Beam Energy, E0

- •20.2.3 Measuring the Beam Current

- •20.2.4 Choosing the Beam Current

- •Optimizing Analysis Strategy

- •20.3.4 Ba-Ti Interference in BaTiSi3O9

- •20.4 The Need for an Iterative Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis Strategy

- •20.4.2 Analysis of a Stainless Steel

- •20.5 Is the Specimen Homogeneous?

- •20.6 Beam-Sensitive Specimens

- •20.6.1 Alkali Element Migration

- •20.6.2 Materials Subject to Mass Loss During Electron Bombardment—the Marshall-Hall Method

- •Thin Section Analysis

- •Bulk Biological and Organic Specimens

- •References

- •21: Trace Analysis by SEM/EDS

- •21.1 Limits of Detection for SEM/EDS Microanalysis

- •21.2.1 Estimating CDL from a Trace or Minor Constituent from Measuring a Known Standard

- •21.2.2 Estimating CDL After Determination of a Minor or Trace Constituent with Severe Peak Interference from a Major Constituent

- •21.3 Measurements of Trace Constituents by Electron-Excited Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry

- •The Inevitable Physics of Remote Excitation Within the Specimen: Secondary Fluorescence Beyond the Electron Interaction Volume

- •Simulation of Long-Range Secondary X-ray Fluorescence

- •NIST DTSA II Simulation: Vertical Interface Between Two Regions of Different Composition in a Flat Bulk Target

- •NIST DTSA II Simulation: Cubic Particle Embedded in a Bulk Matrix

- •21.5 Summary

- •References

- •22.1.2 Low Beam Energy Analysis Range

- •22.2 Advantage of Low Beam Energy X-Ray Microanalysis

- •22.2.1 Improved Spatial Resolution

- •22.3 Challenges and Limitations of Low Beam Energy X-Ray Microanalysis

- •22.3.1 Reduced Access to Elements

- •22.3.3 At Low Beam Energy, Almost Everything Is Found To Be Layered

- •Analysis of Surface Contamination

- •References

- •23: Analysis of Specimens with Special Geometry: Irregular Bulk Objects and Particles

- •23.2.1 No Chemical Etching

- •23.3 Consequences of Attempting Analysis of Bulk Materials With Rough Surfaces

- •23.4.1 The Raw Analytical Total

- •23.4.2 The Shape of the EDS Spectrum

- •23.5 Best Practices for Analysis of Rough Bulk Samples

- •23.6 Particle Analysis

- •Particle Sample Preparation: Bulk Substrate

- •The Importance of Beam Placement

- •Overscanning

- •“Particle Mass Effect”

- •“Particle Absorption Effect”

- •The Analytical Total Reveals the Impact of Particle Effects

- •Does Overscanning Help?

- •23.6.6 Peak-to-Background (P/B) Method

- •Specimen Geometry Severely Affects the k-ratio, but Not the P/B

- •Using the P/B Correspondence

- •23.7 Summary

- •References

- •24: Compositional Mapping

- •24.2 X-Ray Spectrum Imaging

- •24.2.1 Utilizing XSI Datacubes

- •24.2.2 Derived Spectra

- •SUM Spectrum

- •MAXIMUM PIXEL Spectrum

- •24.3 Quantitative Compositional Mapping

- •24.4 Strategy for XSI Elemental Mapping Data Collection

- •24.4.1 Choosing the EDS Dead-Time

- •24.4.2 Choosing the Pixel Density

- •24.4.3 Choosing the Pixel Dwell Time

- •“Flash Mapping”

- •High Count Mapping

- •References

- •25.1 Gas Scattering Effects in the VPSEM

- •25.1.1 Why Doesn’t the EDS Collimator Exclude the Remote Skirt X-Rays?

- •25.2 What Can Be Done To Minimize gas Scattering in VPSEM?

- •25.2.2 Favorable Sample Characteristics

- •Particle Analysis

- •25.2.3 Unfavorable Sample Characteristics

- •References

- •26.1 Instrumentation

- •26.1.2 EDS Detector

- •26.1.3 Probe Current Measurement Device

- •Direct Measurement: Using a Faraday Cup and Picoammeter

- •A Faraday Cup

- •Electrically Isolated Stage

- •Indirect Measurement: Using a Calibration Spectrum

- •26.1.4 Conductive Coating

- •26.2 Sample Preparation

- •26.2.1 Standard Materials

- •26.2.2 Peak Reference Materials

- •26.3 Initial Set-Up

- •26.3.1 Calibrating the EDS Detector

- •Selecting a Pulse Process Time Constant

- •Energy Calibration

- •Quality Control

- •Sample Orientation

- •Detector Position

- •Probe Current

- •26.4 Collecting Data

- •26.4.1 Exploratory Spectrum

- •26.4.2 Experiment Optimization

- •26.4.3 Selecting Standards

- •26.4.4 Reference Spectra

- •26.4.5 Collecting Standards

- •26.4.6 Collecting Peak-Fitting References

- •26.5 Data Analysis

- •26.5.2 Quantification

- •26.6 Quality Check

- •Reference

- •27.2 Case Study: Aluminum Wire Failures in Residential Wiring

- •References

- •28: Cathodoluminescence

- •28.1 Origin

- •28.2 Measuring Cathodoluminescence

- •28.3 Applications of CL

- •28.3.1 Geology

- •Carbonado Diamond

- •Ancient Impact Zircons

- •28.3.2 Materials Science

- •Semiconductors

- •Lead-Acid Battery Plate Reactions

- •28.3.3 Organic Compounds

- •References

- •29.1.1 Single Crystals

- •29.1.2 Polycrystalline Materials

- •29.1.3 Conditions for Detecting Electron Channeling Contrast

- •Specimen Preparation

- •Instrument Conditions

- •29.2.1 Origin of EBSD Patterns

- •29.2.2 Cameras for EBSD Pattern Detection

- •29.2.3 EBSD Spatial Resolution

- •29.2.5 Steps in Typical EBSD Measurements

- •Sample Preparation for EBSD

- •Align Sample in the SEM

- •Check for EBSD Patterns

- •Adjust SEM and Select EBSD Map Parameters

- •Run the Automated Map

- •29.2.6 Display of the Acquired Data

- •29.2.7 Other Map Components

- •29.2.10 Application Example

- •Application of EBSD To Understand Meteorite Formation

- •29.2.11 Summary

- •Specimen Considerations

- •EBSD Detector

- •Selection of Candidate Crystallographic Phases

- •Microscope Operating Conditions and Pattern Optimization

- •Selection of EBSD Acquisition Parameters

- •Collect the Orientation Map

- •References

- •30.1 Introduction

- •30.2 Ion–Solid Interactions

- •30.3 Focused Ion Beam Systems

- •30.5 Preparation of Samples for SEM

- •30.5.1 Cross-Section Preparation

- •30.5.2 FIB Sample Preparation for 3D Techniques and Imaging

- •30.6 Summary

- •References

- •31: Ion Beam Microscopy

- •31.1 What Is So Useful About Ions?

- •31.2 Generating Ion Beams

- •31.3 Signal Generation in the HIM

- •31.5 Patterning with Ion Beams

- •31.7 Chemical Microanalysis with Ion Beams

- •References

- •Appendix

- •A Database of Electron–Solid Interactions

- •A Database of Electron–Solid Interactions

- •Introduction

- •Backscattered Electrons

- •Secondary Yields

- •Stopping Powers

- •X-ray Ionization Cross Sections

- •Conclusions

- •References

- •Index

- •Reference List

- •Index

169 |

11 |

11.3 · Selecting the Beam Energy to Control the Spatial Sampling of Imaging Signals

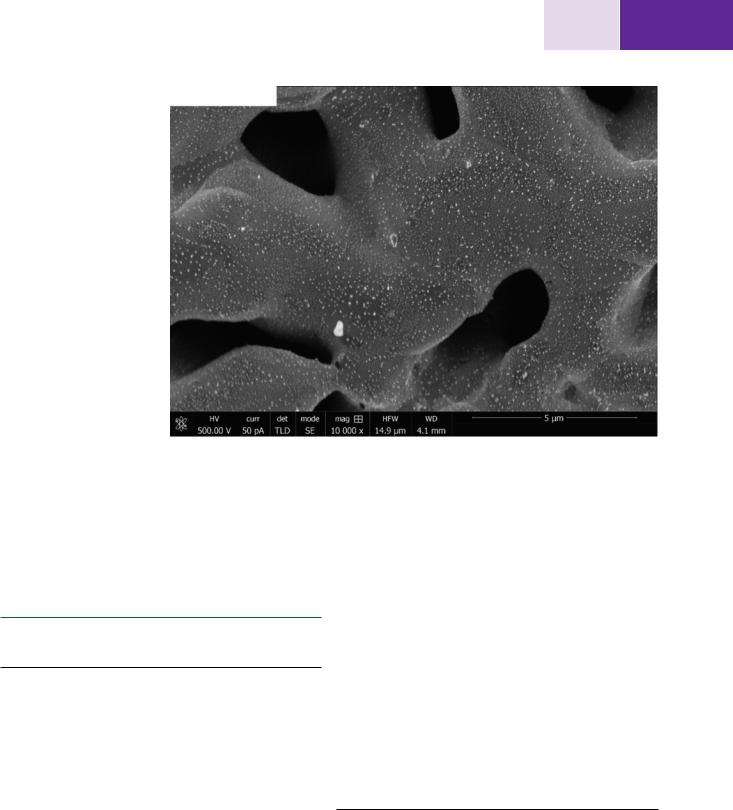

. Fig. 11.5 SEM image of a

silver filter obtained at E0 = 0.5 keV Ag filter, E0 = 500 eV with a through-the-lens

secondary electron detector; Bar = 5 µm (Image courtesy of Keana Scott, NIST)

unless an ultrahigh vacuum instrument is used, where the chamber pressure is <10−8 Pa (10−10 torr).

11.3\ Selecting the Beam Energy to Control the Spatial Sampling of Imaging Signals

11.3.1\ Low Beam Energy for High Lateral Resolution SEM

The electron range controls the lateral spatial distribution of the backscattered electrons: 90 % of BSEs escape radially from approximately 30 % RK-O (high Z) to 60 % RK-O (low Z). The lateral spatial distribution of the SE2, which is created as the BSE escape through the surface, and the SE3, which is the BSE-to-SE conversion signal that results when BSE strike the objective lens pole piece, the stage components, and the chamber walls, effectively sample the same spatial range as the BSE. As the incident beam energy is lowered, the BSE (SE3) and SE2 signal lateral distributions collapse onto the SE1 distribution, which is restricted to the beam footprint, so that at sufficiently low beam energy all of these signals carry high spatial resolution information similar to the SE1. With a modern high performance SEM equipped with a high brightness source, for example, a cold field emission gun or a Schottky thermally assisted field emission gun, capable of delivering a useful beam current into a nanometer or sub-nanometer diameter beam, low beam energy SEM operation has become the

most frequent choice to achieve high lateral spatial resolution imaging of bulk specimens, as discussed in detail in the “High Resolution SEM” module. An example of high spatial resolution achieved at low beam energy is shown in

. Fig. 11.5 for a silver filter material imaged at E0 = 0.5 keV with a “through-the-lens” secondary electron detector. Unfortunately, there is no simple rule like η vs. Z at high beam energy for interpreting the contrast seen in this image. For example, why does the population of nanoscale particles appear extremely bright against the general midlevel gray of the bulk background of the silver structure. These features may appear bright because of local compositional differences such as thicker oxides or there may be a physical change such as increased surface area for SE emission due to nanoscale roughening.

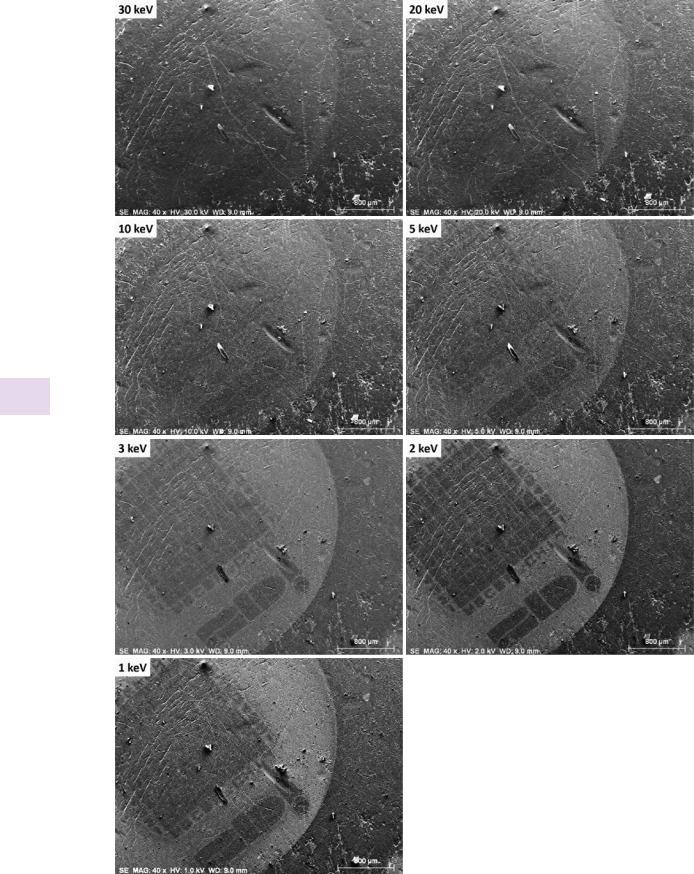

11.3.2\ Low Beam Energy for High Depth Resolution SEM

The strong exponential dependence of the beam penetration on the incident energy controls the sampling of sub-surface specimen properties by the BSEs and SEs, which can provide insight on the depth dimension. Observing a specimen as the beam energy is progressively lowered to record systematic changes can reveal lateral heterogeneities in surface composition. . Fig. 11.6 shows such a sequence of images from high beam energy (30 keV) to low beam energy (1 keV) prepared with an E–T(positive bias) detector where the specimen is an aluminum stub upon which was deposited approximately

\170 Chapter 11 · Low Beam Energy SEM

30 keV |

a |

20 keV |

b |

10 keV |

c |

5 keV |

d |

11

3 keV |

e |

2 keV |

f |

1 keV |

g |

. Fig. 11.6 Beam energy series of images of a carbon film, nominally 7 nm thick, deposited on an aluminum SEM stub in the as-received condition prepared with an E–T(positive bias) detector: a 30 keV; b 20 keV; c 10 keV; d 5 keV; e 3 keV; f 2 keV; g 1 keV; Bar = 800 μm

171 |

11 |

11.3 · Selecting the Beam Energy to Control the Spatial Sampling of Imaging Signals

7 nm of carbon shadowed through a grid. The contrast between the carbon and the aluminum behaves in a complex fashion. The C-Al contrast is only weakly visible above E0 = 5 keV despite a high electron dose, long image integration, and post-acquisition image processing for contrast enhancement. The C-Al contrast increases sharply as the beam energy decreases below 5 keV, reaching a maximum at E0 = 2 keV and then decreasing below this energy. The increase in contrast below 5 keV is consistent with the increasing separation between the values of δ for C and Al seen in . Fig. 11.2. The eventual decrease in the C-Al contrast below E0 = 2 keV is not consistent with the measurements plotted in . Fig. 11.2, where the difference between δ for C and Al actually increases below E0 = 2 keV, which should increase the contrast. Despite the difficulty in interpreting these trends in contrast, this example demonstrates that lateral differences in the surface can be detected, provided care is taken to fully explore the image response to changing the beam energy parameter.

11.3.3\ Extremely Low Beam Energy Imaging

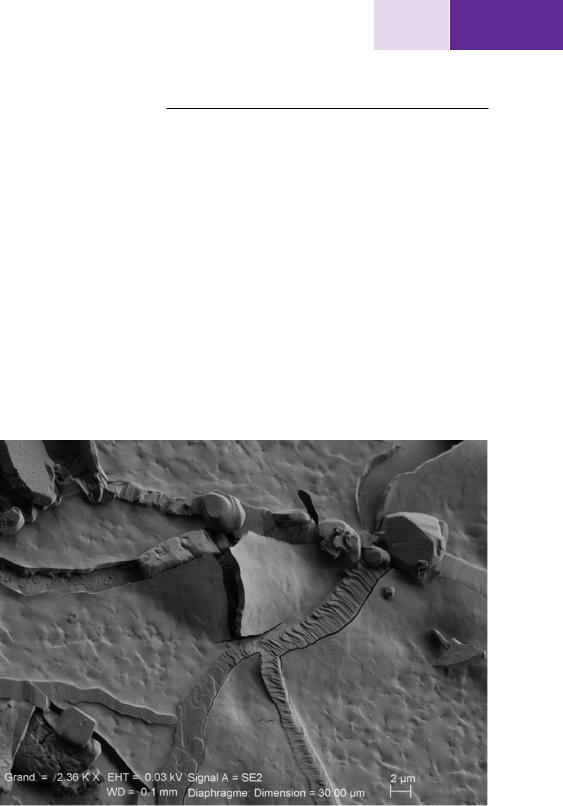

High performance SEMs typically operate down to beam energies below 0.5 keV, with the lower limit depending on the vendor and the particular model. Ultralow beam energies below 0.1 keV can be achieved through different electron- optical techniques, including biasing the specimen to –V. Specimen biasing acts to decelerate the beam electrons emitted at energy E0 from the column so that the landing energy, that is, the kinetic energy remaining when the beam electrons reach the specimen surface, is E0 –eV, where e represents the electronic charge. Ultralow beam energy imaging is illustrated in . Fig. 11.7, where the surface of a silica (SiO2) specimen is imaged at a landing energy of 0.030 keV (30 eV).

. Figure 11.8 shows gold islands on carbon imaged with a landing energy of 0.01 keV (10 eV). At such low incident energy, only the outermost atomic/molecular layers are probed by the beam.

. Fig. 11.7 Extremely low landing energy (E0 = 0.030 keV) SEM image of silica (SiO2) prepared with an Everhart-Thorn- ley E–T(positive bias) detector and a beam current of 250 pA revealing fine-scale texture and surface topography; Bar = 2 µm (Image courtesy of Carl Zeiss)