2132

.pdf10 July 2010 |

|

July 10, 2010 |

10th July 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

Accepted in Great Britain |

Accepted in the USA |

8. Read the following letter and say what variant this letter refers to (British or American):

Amazing Computers Enterprised

768 Capitol Drive, San Jose

Balanga city

April 3, 2009

Miss Andrea de Guzman Harris Corporation Headquarters 1025 West NASA Boulevard Melbourne, Florida 32919-0001

Dear Ms. Andrea de Guzman:

In reverence to your valuable time I would like to get straight to the point and express our deep apology for what happened last time.

The purchase order that we received from you on March 25th, 2009 clearly stated 10 cases and it is our error regarding the shipment of the product.

However, please be informed that to make up with the said mistake, there are two options available at this time. The first one is that, you can opt to keep the merchandise and we will just bill you thirty days from now. The second one is that, we will do our best to have it picked up at your loading dock and then issue a credit to you.

I will greatly appreciate it if you will let me know your preference between the two. We will ensure that this type of error will occur again.

Please let me know if you need assistance regarding this one. Feel free to call me and I will be glad to help you.

Thank you for your kind consideration.

Yours truly

E. Tinao

Eireen Tinao,

Assistant Manager

9. Read the letter which should be written according to the rules accepted in Great Britain. Find mistakes in this letter and correct them.

Zope Corporation

10300 Spotsylvania Ave. Suite 101

Fredericksburg, VA 22408

Tom Atkinson

Market Harborough Road

PERI Ltd

Clifton upon Dunsmore

Rugby,

England, CV23 0AN.

January 2, 2008

Dear Mr. Tom Atkinson,

Thank you for taking the time to fill out our questionnaire during your stay with us. We do appreciate hearing from our customers, as their comments are vital for us to continue improving our accommodations.

The problems that you mentioned have been brought to the attention of our management. While the lack of service you experienced is unusual and not the standard of our company, there is no excuse for a lackadaisical attitude on the part of any of our employees. We are sorry for the inconvenience and annoyance this incident caused.

Thank you again for your comments. We hope that you will give us another chance to serve you.

Yours faithfully

J. Coup

Jennifer Coup

Manager of shipping department

PART II

HISTORY

OF ROADS

READING

1. Read the following words and learn them by heart:

route – дорога, путь, шоссе, магистраль

We live on a rural route.

trail – след, тропа, временная дорога

Stay on the trail if we get separated.

track – 1) тропинка, проселочная дорога 2) ж.-д. колея, рельсовый путь

Follow the track into the forest.

causeway – мощеная дорога; гать, насыпная дорога

The island is linked by a causeway to the mainland. highway – большая дорога, большак; шоссе, магистраль

I had heard there was a traffic jam on the highway, so I took the side roads. to pave – мостить

Old roads used to be paved with round stones.

to maintain – поддерживать, сохранять, содержать

The authorities have done a poor job of maintaining district roads. bedding – 1) основание, фундамент; 2) постель (из раствора), подстил

Crushed stone is used in construction and in the bedding of roads. mortar – строительный раствор

The first mortars were made of mud and clay. lime – 1) известь; окись кальция (CaO)

Mortars are made from a mixture of sand, a binder such as lime, and water. tar – смола, деготь, гудрон

During the earlyand mid-20th century tar was a readily available product and extensively used as the binder for road aggregates.

timber – древесина, деревянный брус, бревно

This house is built of timber. concrete – бетон

Concrete has been used for construction in various ancient civilizations. coarse – крупнозернистый

Coarse, porous materials will suck up water during the mixing process, requiring the addition of more water to compensate.

fine – мелкозернистый

Sand is a common example of a fine aggregate.

to ascend – 1) подниматься; 2) всходить, взбираться, подниматься

Several paths ascend to the top of the mountain. steep – 1) крутой, резкий; 2) крутой подъём \ спуск

This hillside is very steep.

incline – 1) наклонная плоскость; наклон, скат (обычно о дороге или железнодорожном полотне)

What is the angle of the incline?

2.Guess the meaning of the following words:

a)basing on their phonetic and graphic similarity with the Russian words: extensive, indicator, fortunate, urban, terrace assist graded, gravel lava;

b)basing on the known English words:

impassable, well-maintained, accessible, midst, at height, to top, paved, maintenance, to crisscross, downfall .

3. Read and translate the following collocations:

the level of development, trade routes, royal highways, the Holy Land, network of roads, draft animals, a carpet of finer, soil foundation.

4. Read the text and find out what the main reasons for building roads in ancient times were:

FROM THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT ROADS

Most of us give very little thought to the roads we drive on every day, and tend to take them for granted at least until they are closed for repairs, washed out in a flood, or in some way rendered impassable. However, only during the past forty years or so have we enjoyed the luxury of a vast, extensive, and wellmaintained system of roads accessible to everyone. In the midst of our grumbling about potholes, traffic jams, and incompetent drivers, we forget how fortunate we truly are. Obviously, it was not always the case.

From the earliest times, one of the strongest indicators of a society’s level of development has been its road system or lack of one. Increasing populations and the advent of towns and cities brought with it the need for communication and commerce between those growing population centers. A road built in Egypt by the Pharaoh Cheops around 2500 BC is believed to be the earliest paved road on record a construction road 1,000 yards long and 60 feet wide that led to the site of the Great Pyramid. Since it was used only for this one job and was never used for travel, Cheops’s road was not truly a road in the same sense that the later trade routes, royal highways, and impressively paved Roman roads were.

The various trade routes, of course, developed where goods were transported from their source to a market outlet and were often named after the goods which traveled upon them. For example, the Amber Route traveled from Afghanistan through Persia and Arabia to Egypt, and the Silk Route stretched 8,000 miles from China, across Asia, and then through Spain to the Atlantic

Ocean. Some other ancient roads were established by rulers and their armies. The Old Testament contains references to ancient roads like the King’s Highway, dating back to 2000 BC. This was a major route from Damascus in Palestine, and ran south to the Gulf of Aqaba, through Syria to Mesopotamia, and finally on to Egypt. Later it was renamed Trajan’s Road by the Romans, and was used in the eleventh and twelfth centuries by the Crusaders when they attempted to “reclaim” the Holy Land. Around 1115 BC the Assyrian Empire in western Asia began what is believed to be the first organized road-building. Since they were trying to dominate that part of the world, they had to be able to move their armies effectively along with supplies and equipment. As the Assyrians gradually faded, another imperial road, the Royal Road, was being built by the Persians from the Persian Gulf to the Aegean Sea, a distance of 1,775 miles.

Without doubt, the champion road builders of them all were the ancient Romans, who, until modern times, built the world’s straightest, best engineered, and most complex network of roads in the world. At their height, the Roman Empire maintained 53,000 miles of roads, which covered all of England to the north, most of Western Europe and crisscrossed the entire Mediterranean area. Famous for their straightness, Roman roads were composed of a graded soil foundation topped by four courses: a bedding of sand or mortar; rows of large, flat stones; a thin layer of gravel mixed with lime; and a thin surface of flint-like lava. Typically they were 3 to 5 feet thick and varied in width from 8 to 35 feet, although the average width for the main roads was from 12 to 24 feet. Their design remained the most sophisticated until the advent of modern road-building technology in the very late 18th and 19th centuries. Many of their original roads are still in use today, although they have been resurfaced numerous times.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, several centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, the Inca Empire began to rise in South America during a period that corresponded with the Middle Ages in Europe. Interestingly enough, the Incas built their empire without inventing the wheel, without the use of draft animals, and without a written language. Because they had no wheeled vehicles to worry about, their roads could ascend steep inclines via terraces. They also built over swamps, and constructed a causeway 24 feet wide and 8 miles long, which had a paved surface and stone walls. Unfortunately, their well-constructed system of roads ultimately assisted in their downfall as the invading Spaniards used the Incas’ own roads to move Spanish armies, weapons, and supplies.

5.Answer the following questions using the information from the text:

1)Why was the road system the strongest indicator of a society’s level of development in ancient times?

2)What country had the best road network in the world?

3)What materials were used for road building in Ancient Rome?

4)What peculiarities did Inca’s roads have and why?

6. Correct this text replacing small letters with capital letters where it is necessary:

Rome was famous for was their system of roads Romans built over 53,000 miles (85,000 kilometers) of roads to connect every part of their empire the roads were mostly built by the army and were all done by hand the system of roads connected together every province in the empire the Romans had a saying “All roads lead to Rome” one could start traveling on a Roman road in northwest Africa, travel around the entire Mediterranean sea, end up in Rome and never have left a Roman road the Roman roads were roads built by the Roman empire, intended for quick transport of material from one location to another, for cattle, vehicles, or any similar traffic along the path they were essential for the growth of the Roman Empire roman roads enabled the Romans to move armies and trade goods and to communicate news when Rome reached the height of its power, no fewer than 29 great military highways radiated from the city hills were cut through and deep ravines filled in at one point, the Roman Empire was divided into 113 provinces traversed by 372 great road links the Romans became adept at constructing roads, which they called viae the viae differed from the many other smaller or rougher roads, bridle-paths and tracks by the laws of the Twelve Tables, the minimum width of a via was fixed at 2.4 m where it was straight, and 4.9 m where it turned the Roman road networks were important both in maintaining the stability of the empire and for its expansion the legions made good time on them, and some are still used millennia later in later antiquity, these roads played an important part in Roman military reverses by offering avenues of invasion to the barbarians.

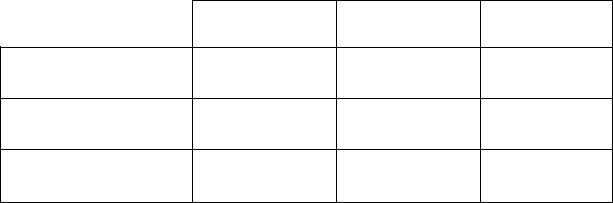

7. Read the text and fill in the following table:

Viae militares |

Viae vicinales Viae privatae |

Type of roads included by the via

Funds of construction and maintenance

Purpose of the via

MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF ROMAN ROADS

Roman roads varied from simple corduroy roads to paved roads using deep roadbeds of tamped rubble as an underlying layer to ensure that they

kept dry, as the water would flow out from between the stones and fragments of rubble, instead of becoming mud in clay soils. According to Ulpian, there were three types of roads: viae publicae, consulares, or militares; viae privatae, glareae or agrariae; viae vicinales.

Viae publicae, consulares, or militares included public high or main roads, constructed and maintained at the public expense, and with their soil vested in

the state. Such roads led either to the sea, or to a town, or to a |

public river, |

or to another public road. Siculus Flaccus (A.D. 98-117) |

describes their |

characteristics as follows: they are placed under curators (commissioners), and repaired by contractors at the public expense; a fixed contribution, however, being levied from the neighboring landowners. These roads bear the names of

their constructors (e.g. Via Appia, Cassia, Flaminia). |

|

If the road was of |

|

unknown origin, it took the name of its destination or of |

the region through |

||

which it mainly passed. A road was renamed if the |

|

curator ordered major |

|

work on it, such as paving, repaving, or rerouting. |

|

But there were many |

|

other persons, besides special officials, who from time |

|

to time, and for a |

|

variety of reasons, sought to connect their names with a |

great public service |

||

like that of the roads. For example, Gaius Gracchus, |

|

when Tribune of the |

|

People (123-122 BC), paved or gravelled many of |

|

the public roads, and |

|

provided them with milestones and mounting-blocks |

for riders. |

|

|

Viae privatae, rusticae, glareae and agrariae included private or |

country |

||

roads, originally constructed by private individuals, in whom their |

soil was |

||

vested, and who had the power to dedicate them to the public use. Such

roads benefited from a right of way, in favor either of the public or of |

the |

owner of a particular estate. Under the heading of viae privatae were |

also |

included roads leading from the public or high roads to particular estates |

or |

settlements. Both main or secondary roads might either be paved, or left unpaved, with a gravel surface, as they were in North Africa. These prepared but unpaved roads were viae glareae or sternendae (“to be strewn”). Beyond the secondary roads were the viae terrenae (“dirt roads”).

Viae vicinales comprised roads at or in villages, districts, or crossroads, leading through or towards a village. Such roads ran either into a high road, or into other viae vicinales, without any direct communication with a high road. They were considered public or private, according to the fact of their original construction out of public or private funds or materials. Such a road, though privately constructed, became a public road when the memory of its private constructors had perished. Siculus Flaccus describes viae vicinales as roads “which turn off the public roads into fields, and often reach to other public roads”. The repairing authorities, in this case, were magistrates of the cantons. They could require the neighboring landowners either to

furnish laborers for the general repair of the viae vicinales, or to keep in repair, at their own expense, a certain length of road passing through their respective properties.

8. Read the text and show Via Appia Antica on the map:

VIA APPIA ANTICA

The Appian Way or Via Appia Antica in Rome is one of the most famous ancient roads. It was built in 312 B.C. by Appius Claudius Caecus. In it’s entirety it spanned 350 miles (563kms).

The Appian Way is visible today and many significant tombs and architecture line its borders. It was this road that many events took place. It might be most famous for its role in the slave revolt lead by Spartacus in 73 B.C. After the Roman army subdued the insurrection they crucified more than 6000 slaves and lined the Appian Way for 130 miles with their bodies.

The Appian Way is also lined with tombs of ancient patrician families of Rome. Among the tombs one will find the Christian catacombs, San Sebastian, San Domitilla, San Callixtus, and the most impressive, the tomb of Cecilia Metella. The Appian Way is so rich in history and significance and is really is a valuable experience. It is said to be the road in which Peter had his vision from Christ and headed back to the city of Rome to be persecuted.

MAIN ROMAN ROADS

1

2 3

4

5

6

1.Via Aemilia

2.Via Cassia

3.Via Flaminia

4.Via Valeria

5.Via Latina

6.Via Appia

Find information about other Romans roads depicted on the map. Present the results of your survey using PowerPoint. (Project work)

9. Study the information about describing a sequence of the stages:

When we tell about a process, firstly we have to say about sequence of the stages. Using numbers is the simplest way to sequence the stages.

Look through the text and study an example:

ROAD MIX SURFACES

Road mixes, at the time often known as “retread”, “oil processed”, “surface mix” or “mixed-in-place” roads, refer to the mechanical mixing of asphalt and aggregate directly on the road bed to form a thin 25-100 mm (1-4 inch) wearing course. Typically, the construction process was as follows:

1)Place, grade and compact the aggregate road bed.

2)Place the asphalt binder.

3)Mix the asphalt binder and aggregate together using a tractor-pulled disk or harrow, windrow the mixed material in the center of the road, turn it, then redistributed across the road and smooth it.

4)Compact the resultant wearing course until no movement is discernible under the roller wheels.

5)After a few weeks to several months, spread a cover coat of fine aggregate over the surface and apply a seal coat.

These pavements were not true hot mix asphalt pavements because the asphalt was often applied as an emulsion and the mixing was done directly on the road.

But instead of numbers (as it is shown above) we can use sequence words. Compare:

Firstplace, grade and compact the aggregate road bed Then place the asphalt binder

Next mix the asphalt binder and aggregate together using a tractor-pulled disk or harrow, windrow the mixed material in the center of the road, turn it, then redistributed across the road and smooth it.

After that (finally), spread a cover coat of fine aggregate over the surface and apply a seal coat.

Try to continue this list of sequence words.

10.Give definitions to the following word combinations:

1)Asphalt binder is … .

2)Wearing course is… .

3)Fine aggregate is… .

4)A seal coat is… .

5)A “mixed-in-place” road is… .

11. Study the meanings of the following roman terms concerning type of roads and the process of road construction and try to keep them in mind:

Summa crusta (surfacing) – smooth, polygonal blocks embedded in the underlying layer.

Nucleus – a kind of base layer composed of gravel and sand with lime cement. Rudus – the third layer was composed of rubble masonry and smaller stones also set in lime mortar.

Statumen – two or three courses of flat stones set in lime mortar.

Groma (gruma) – the principal Roman surveying instrument which comprised a vertical staff with horizontal cross pieces mounted at right-angles on a bracket. Each cross piece had a plumb line hanging vertically at each end. It was used to survey straight lines and right-angles, thence squares or rectangles.

Read the text and according to the given information enumerate the stages of the process of road building in Ancient Rome. Usesequence words.

Via were distinguished not only according to their public or private character, but according to the materials employed and the methods followed in their construction. Ulpian divided them up in the following fashion: via terrene – a plain road of leveled earth; via glarea – an earthed road with a graveled surface; via munita – a regular built road, paved with rectangular blocks of the stone of the country, or with polygonal blocks of lava.

After the civil engineer looked over the site of the proposed road and determined roughly where it should go, the surveyors went to work exploring the road bed. They used two main devices, the rod and a device called a groma, which helped them obtain right angles. The gromatici, the Roman equivalent of rod men, placed rods and put down a line called the rigor. A civil engineering surveyor tried to achieve straightness by looking along the rods and commanding the gromatici to move them as required. Using the groma they then laid out a grid on the plan of the road.

The workmen then began their work using ploughs and, sometimes with the help of legionaries, with spades excavated the road bed down to bed rock or at least to the firmest ground they could.

The method varied according to geographic locality, materials available and terrain, but the plan, or ideal at which the architect aimed was always the same. The roadbed was layered. The road was constructed by filling the ditch. This was done by layering rock over other stones.

Into the fossa was dumped large amounts of rubble, gravel and stone, whatever fill was available. Sometimes a layer of sand was put down, if it could be found. When it came to within 1 yd (1 m) or so of the surface it was covered with gravel and tamped down, a process called pavimentare. The flat surface was then the pavimentum. It could be used as the road, or additional layers could be constructed. A statumen or foundation of flat stones set in cement might support the additional layers.

The final steps utilized concrete, which the Romans had exclusively rediscovered. They seem to have mixed the mortar and the stones in the fossa. First a small layer of coarse concrete, the rudus, then a little layer of fine concrete, the nucleus, went onto the pavement or statumen. Onto the nucleus went a layer of polygonal or square paving stones, called the summa crusta. The upper surface was designed to cast off rain or water like the shell of a tortoise. The lower surfaces of the separate stones, here shown as flat, were sometimes cut to a point or edge in order to grasp the nucleus, or next layer, more firmly.