- •Учебно-методический комплекс дисциплины

- •Астана 2011 Силлабус

- •6 Список основной и дополнительной литературы

- •6.1 Основная литература

- •7 Контроль и оценка результатов обучения

- •7.1 Виды контроля

- •7.2 Формы контроля

- •8 Политика учебной дисциплины

- •Глоссарий по учебной дисциплине

- •Kонспект лекций.

- •Block 1. The Writing Process

- •Looking for Subjects

- •Exploring for Topics

- •Block 1. The Writing Process

- •Making a Plan

- •Drafts and Revisions

- •Block 2. The essay Theme: “Beginning. Closin”

- •Beginning

- •Interesting the Reader

- •Closing

- •Block 2. The essay Theme: “Organizing the Middle. Point of View, Persona and Tone”

- •Organizing the Middle

- •Point of View

- •Block 3. The Expository Paragraph

- •Basic Structure

- •Paragraph Unity

- •Block 3. The Expository Paragraph

- •Paragraph Development: (1) Illustration and Restatement

- •Block 3. The Expository Paragraph

- •Paragraph Development: (3) Cause and Effect

- •The Sentence: a Definition

- •Sentence Styles

- •Concision

- •Emphasis

- •Variety

- •Meaning

- •Clarity and Simplicity

- •Concision

- •Figurative Language

- •Unusual Words and Collocations

- •Narration

- •The Other Marks

- •Основная и дополнительная литература

- •Задания для Cеминарских занятий

- •Материалы для рейтинга

- •Рекомендации по выполнению заданий:

- •Содержание

The Sentence: a Definition

Good sentences are the sinew of style. They give to prose its forward thrust, its flexibility, its strong and subtle rhythms. The cardinal virtues of such sentences are clarity, emphasis, concision, and variety. How to achieve these qualities will be our major concern in this part. First, however, we must understand, in a brief and rudimentary way, what a sentence is.

It is not easy to say. In fact, it is probably impossible to define a sentence to everyone's satisfaction. On the simplest level it may be described as a word or group of words standing by itself, that is, beginning with a capital letter and ending with a period, question mark, or exclamation point. (In speech the separateness of a sentence is marked by intonation and pauses.)

And yet an effective sentence involves more than starting with a capital and stopping with a period. The word or words must make sense, expressing an idea or perception or feeling clear enough to stand alone. For example, consider these two sentences:

The package arrived. Finally.

The first consists of a subject and verb. The second is only a single word, an adverb detached from a verb (arrived). The idea might have been expressed in one sentence:

The package finally arrived.

The package arrived, finally.

Finally, the package arrived.

But we can imagine a situation in which a speaker or writer, wanting to stress exasperation, feels that finally should be a sentence by itself.

As that example indicates, there are sentences which contain subjects and verbs and sentences which do not. The first kind (The package arrived) is "grammatically complete" and is the conventional form sentences take in composition. The second type of sentence (Finally in our example) does not contain a subject and verb and is called a fragment. Fragments are more common in speech than in writing, but even in formal composition they have their place, which we'll consider in a subsequent chapter.

The Grammatical Sentence

The grammatically complete sentence is independent, contains a subject and a predicate, and is properly constructed. That definition may sound a bit formidable, but it really isn't. Let's briefly consider each of those three criteria.

Grammatical Independence

Grammatical independence simply means that the words constituting the sentence are not acting as a noun or modifier or verb in connection with any other word or words. For example, Harry was late is independent. Became Harry was late is not. Because turns the words into an adverb (more exactly, an adverbial clause). The construction should modify another verb or clause as in The men were delayed in starting because Harry was late.

To take one more case. They failed to agree is a grammatical sentence. That they failed to agree is not. It is a noun clause and could function as the subject of a verb:

That they failed to agree was unfortunate.

Or as the object of one:

We know that they failed to agree.

Subject and Predicate

The heart of a grammatical sentence is the subject and predicate. In a narrow sense the subject is the word or words identifying who or what the sentence is about, and the predicate is the verb, expressing something about the subject. In a broader sense, the subject includes the subject word(s) plus all modifiers, and the predicate in cludes the verb together with its objects and modifiers. For instance in The man who lives next door decided last week to sell his house, the narrow, or grammatical, subject is man, and the narrow, or grammatical, verb is decided. The broad, or notional, subject is The man who lives next door, and the broad, or notional, predicate is decided last week to sell his house.

The verb in a grammatical sentence must be finite, that is, limited with reference to time or person or number. English has several nonfinite verb forms called participles and infinitives (being, for example, and to be). These can refer to any interval of time and can be used with any person or with either number. But by convention these nonfinite forms cannot by themselves make a sentence. Thus Harry was late is a grammatical sentence, but Harry being late isn't because it contains only the participle being instead of a finite form such as was.

Proper Construction

Even though a group of words is grammatically independent and contains a subject and a finite verb, it will not qualify as a grammatical sentence unless it is put together according to the rules. "Rules" here does not mean regulations arbitrarily laid down by experts. It means how we, all of us, use English. Thus Harry late was is not a good sentence. We simply do not arrange these words in that order.

Here's one other example of a non-sentence resulting from bad construction:

Harry was late, and although he was sorry.

And can only combine elements that are grammatically equal—two or more subjects of the same verb, for instance. In this case and joins two unequal constructions—the independent clause Harry was late and the dependent (adverbial) clause although he was sorry. The construction can be turned into a legitimate grammatical sentence in either of two ways:

Harry was late, although he was sorry.

Harry was late, and he was sorry.

The Building Blocks

The basic slots of a grammatical sentence—that is, the subject, verb, object, and modifier—may be filled by many kinds of words, phrases, and dependent clauses, the building blocks of sentences.

Phrases and dependent clauses are both functional word groups—two or more words acting collectively in a grammatical function, as a subject, for instance, or direct object or adverb, and so on. Functional word groups are enormously important. They enable us to treat ideas too complex to be expressed in single words as though they were, grammatically, only one word. Take these two sentences:

I know Susan.

I know that you won't like that movie.

Susan is the direct object of know. So is that you won't like that movie. For purposes of grammar the six-word clause functions like the one-word proper noun. Being able to use the full range of functional word groups available in English is essential to writing well. Here is a quick summary.

Phrases

A phrase is a functional word group that does not contain a subject-finite verb combination, although some phrases do use nonfinite verb forms. We can distinguish five kinds of phrases: verb, prepositional, participial, gerundive, and infinitive.

A verb phrase is a main verb plus any auxiliaries:

They have been calling all day.

A prepositional phrase consists of a preposition (in, of, to, and so on) plus an object, plus (often though not invariably) modifiers of the object:

Three people were sitting on the beautiful green lawn.

The chief function of prepositional phrases is to modify, either as adjectives or as adverbs. A participial phrase is constructed around a participle, usually in the present (running, for example) or past (run) participle form. It acts as an adjective:

The man running down the street seemed suspicious.

Here the participial phrase modifies man. A gerundive phrase also uses the present participle but in a construction that functions as a noun. In the following example the gerundive phrase is the subject of the verb phrase can be:

Running for political office can be very expensive.

An infinitive phrase, finally, is built around one of the infinitives (usually the active present—for example, to run). Infinitive phrases may act either as nouns or as modifiers. In this sentence the phrase is the direct object of the verb, a nounal function:

They want me to go to medical school.

Here it is an adjective modifying time:

We had plenty of time to get there and back.

Clauses

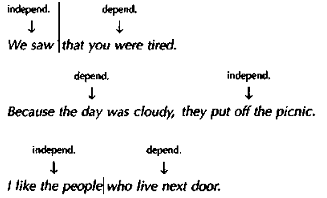

A clause is a functional word group that does contain a subject and a finite verb. There are two basic clauses—independent and dependent. An independent clause can stand alone as a sentence. In fact a simple sentence like We saw you coming is an independent clause. But usually the term is reserved for such a construction when it occurs as part of a larger sentence. The sentence below, for instance, consists of two independent clauses:

We saw you coming, and we were glad.

A dependent clause cannot stand alone as a grammatically complete sentence. It serves as part of a sentence—a subject, object, adjective, or adverb. If we were to place when before the opening clause in the example above, we would turn it into a dependent (adverbial) clause modifying the second clause (which remains independent):

When we saw you coming we were glad.

Dependent clauses may also act as nouns, either as subjects (as in the first of the following sentences) or as objects (as in the second):

Why he went at all is a mystery to me.

We knew that she would be pleased.

And as adjectives:

The point that you're trying to make just isn't very clear.

Absolutes

An absolute is something more than a functional word group but less than a sentence. It is connected by idea but not through grammar to the rest of the statement in which it occurs:

She flew down the stairs, her children tumbling after her.

This absolute tells us something about the circumstances attending the lady's rush downstairs, but it doesn't modify anything in the main clause, nor is it an object or a subject. It simply is not a grammatical part of that clause. (The term absolute derives from a Latin word meaning "free, unrestricted.")

The Basic Types of Grammatical Sentences

Depending on the number and type of clauses they contain, grammatical sentences fall into three patterns: the simple, the compound, and the complex. In addition, there are compound-complex sentences, though they are not truly basic.

The Simple Sentence

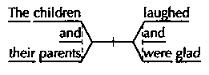

Simple sentences consist of one subject-verb nexus (Nexus means a grammatical connection between words, as in The children laughed.) Usually a simple sentence has only one subject and one verb, but it may have—and many do—several of each and remain simple, providing that the various subjects and verbs comprise a single connection, as in the sentence The children and their parents laughed and were glad, in which the single nexus may be indicated like this:

The Compound Sentence

A compound sentence consists of at least two independent subject-verb nexuses:

The children laughed, and their parents were glad.

Compound sentences often have three independent clauses or even four or five. In theory there is no limit. In practice, however, most compound sentences contain only two clauses. Stringing out a number is likely to make an awkward, rambling sentence.

The two (or more) independent clauses comprising a compound sentence may be united in two ways. One is coordination, connecting clauses by a coordinating conjunction—and, but, for, or, nor, either... or, neither... nor, not only ... but also, both .. . and:

The sea was dark and rough, and the wind was strong from the east.

The second method of joining clauses is parataxis, which is simply butting them together without a conjunction (conventionally they are punctuated by a semicolon):

The sea was dark and rough; the wind was strong from the east.

As we shall see later (Chapter 19) these two ways of connecting independent clauses are not necessarily interchangeable. In most cases one will be better than the other.

The Complex Sentence

A complex sentence contains one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. Here are several examples:

In a complex sentence the independent clause is called the main clause, and the dependent clause—which always functions as a noun or adverb or adjective—is called the subordinate. Of course a complex sentence may contain a number of subordinate clauses, but it can only have one main clause.This type of sentence is very important in composition, and we shall study it more closely in Chapter 19.

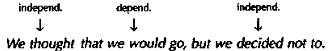

The Compound-Complex Sentence

A compound-complex sentence must have at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent:

Summary

1. A sentence is a group of words (and sometimes a single word) that makes sense standing alone.

2. Some sentences are grammatically complete; others—called fragments—are not.

3. Grammatical sentences must satisfy three criteria: they must (a) be grammatically independent, (b) have a subject and a finite verb, and (c) be properly constructed.

4. The parts of a sentence are subject, verb, object, and modifier.

5. These parts may be filled by single words or by functional word groups.

6. Functional word groups act grammatically as though they were one word. They include phrases and dependent clauses.

7. A phrase does not contain a subject-finite verb combination, though it may have a subject and a nonfinite verb form, either a participle or an infinitive.

8. There are several kinds of phrases—verb phrases, prepositional, participial, gerundive, and infinitive.

9. Clauses may be independent or dependent. Only dependent clauses act as functional word groups.

10. Dependent clauses are classified according to their grammatical role as noun, adverbial, or adjectival clauses.

11. An absolute is more than a functional word group but less than a sentence. It is related in idea but not in grammar to the rest of the sentence in which it occurs.

12. Grammatical sentences come in three basic types—simple, compound, and complex—plus a combination of the last two, the compound-complex sentence.