Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Medical Causes

Aortic insufficiency. With acute aortic insufficiency, pulse pressure widens progressively as the valve deteriorates, and a bounding pulse and an atrial or a ventricular gallop develop. These signs may be accompanied by chest pain; palpitations; pallor; strong, abrupt carotid pulsations; pulsus bisferiens; and signs of heart failure, such as crackles, dyspnea, and jugular vein distention. Auscultation may reveal several murmurs, such as an early diastolic murmur (common) and an apical diastolic rumble (Austin Flint murmur).

Arteriosclerosis. With arteriosclerosis, reduced arterial compliance causes progressive widening of pulse pressure, which becomes permanent without treatment of the underlying disorder. This sign is preceded by moderate hypertension and accompanied by signs of vascular insufficiency, such as claudication, angina, and speech and vision disturbances.

Febrile disorder. A fever can cause widened pulse pressure. Accompanying symptoms vary depending on the specific disorder.

Increased ICP. Widening pulse pressure is an intermediate to late sign of increased ICP. Although a decreased LOC is the earliest and most sensitive indicator of this life-threatening condition, the onset and progression of widening pulse pressure also parallel rising ICP. (A gap of 50 mm Hg can signal a rapid deterioration in the patient’s condition.) Assessment reveals Cushing’s triad: bradycardia, hypertension, and respiratory pattern changes. Other findings include a headache, vomiting, and impaired or unequal motor movement. The patient may also exhibit vision disturbances, such as blurring or photophobia, and pupillary changes.

Special Considerations

If the patient displays increased ICP, continually reevaluate his neurologic status and compare your findings carefully with those of previous evaluations. Be alert for restlessness, confusion, unresponsiveness, or a decreased LOC. Keep in mind, however, that increasing ICP is commonly signaled by subtle changes in the patient’s condition rather than the abrupt development of any one sign or symptom.

Patient Counseling

Explain needed dietary modifications, such as restricting sodium and saturated fats. Stress the importance of planning rest periods. If the patient has a decreased LOC, discuss specific safety measures to implement.

Pediatric Pointers

Increased ICP causes widened pulse pressure in a child. Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) can also cause it, but this sign may not be evident at birth. The older child with PDA experiences exertional dyspnea, with pulse pressure that widens even further on exertion.

Geriatric Pointers

Recently, widened pulse pressure has been found to be a more powerful predictor of cardiovascular events in elderly patients than either increased systolic or diastolic blood pressure.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pulse Rhythm Abnormality

An abnormal pulse rhythm is an irregular expansion and contraction of the peripheral arterial walls. It may be persistent or sporadic and rhythmic or arrhythmic. Detected by palpating the radial or carotid pulse, an abnormal rhythm is typically reported first by the patient, who complains of palpitations. This important finding reflects an underlying cardiac arrhythmia, which may range from benign to life threatening. Arrhythmias are commonly associated with cardiovascular, renal, respiratory, metabolic, and neurologic disorders as well as the effects of drugs, diagnostic tests, and treatments. (See

Abnormal Pulse Rhythm: A Clue to Cardiac Arrhythmias, pages 604 to 607.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Quickly look for signs of reduced cardiac output, such as a decreased level of consciousness (LOC), hypotension, or dizziness. Promptly obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG) and possibly a chest X-ray, and begin cardiac monitoring. Insert an I.V. line for administration of emergency cardiac drugs, and give oxygen by nasal cannula or mask. Closely monitor the patient’s vital signs, pulse quality, and cardiac rhythm because accompanying bradycardia or tachycardia may result in poor tolerance of the abnormal rhythm and cause further deterioration of cardiac output. Keep emergency intubation, cardioversion, defibrillation, and suction equipment handy.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask if he’s experiencing pain. If so, find out about its onset and location. Does the pain radiate? Ask about a history of heart disease and treatment for arrhythmias. Obtain a drug history, and check the patient’s compliance. Also, ask about caffeine or alcohol intake. Digoxin toxicity, cessation of an antiarrhythmic, and the use of quinidine, a sympathomimetic (such as epinephrine), caffeine, or alcohol may cause arrhythmias.

Next, check the patient’s apical and peripheral arterial pulses. An apical rate exceeding a peripheral arterial rate indicates a pulse deficit, which may also cause associated signs and symptoms of low cardiac output. Evaluate heart sounds: A long pause between S 1 (lub) and S2 (dub) may indicate a conduction defect. A faint or absent S 1 and an easily audible S2 may indicate atrial fibrillation or flutter. You may hear the two heart sounds close together on certain beats — possibly indicating premature atrial contractions — or other variations in heart rate or rhythm. Take the patient’s apical and radial pulses while you listen for heart sounds. With some arrhythmias, such as premature ventricular contractions, you may hear the beat with your stethoscope but not feel it over the radial artery. This indicates an ineffective contraction that failed to produce a peripheral pulse. Next, count the apical pulse for 60 seconds, noting the frequency of skipped peripheral beats. Report your findings to the physician.

Medical Causes

Arrhythmias. An abnormal pulse rhythm may be the only sign of a cardiac arrhythmia. The patient may complain of palpitations, a fluttering heartbeat, or weak and skipped beats. Pulses may be weak and rapid or slow. Depending on the specific arrhythmia, dull chest pain or discomfort and hypotension may occur. Associated findings, if any, reflect decreased cardiac output. Neurologic findings, for example, include confusion, dizziness, light-headedness, a decreased LOC and, sometimes, seizures. Other findings include decreased urine output, dyspnea, tachypnea, pallor, and diaphoresis.

Special Considerations

The patient may require cardioversion therapy, before which, he may need to be sedated. Prepare the patient for transfer to a cardiac or intensive care unit. If the patient remains in your care, he may require bed rest or help with ambulation, depending on his condition. To prevent falls and injury, raise the side rails of his bed and don’t leave him unattended while he’s sitting or walking. Check his vital signs frequently to detect bradycardia, tachycardia, hypertension or hypotension, tachypnea, and dyspnea. Also, monitor intake, output, and daily weight.

Collect blood samples for serum electrolyte, cardiac enzyme, and drug level studies. Prepare the patient for a chest X-ray and 12-lead ECG. If possible, obtain a previous ECG with which to compare current findings. Prepare the patient for 24-hour Holter monitoring. Explain to the patient the importance of keeping a diary of his activities and any symptoms that develop to correlate with the incidence of arrhythmias.

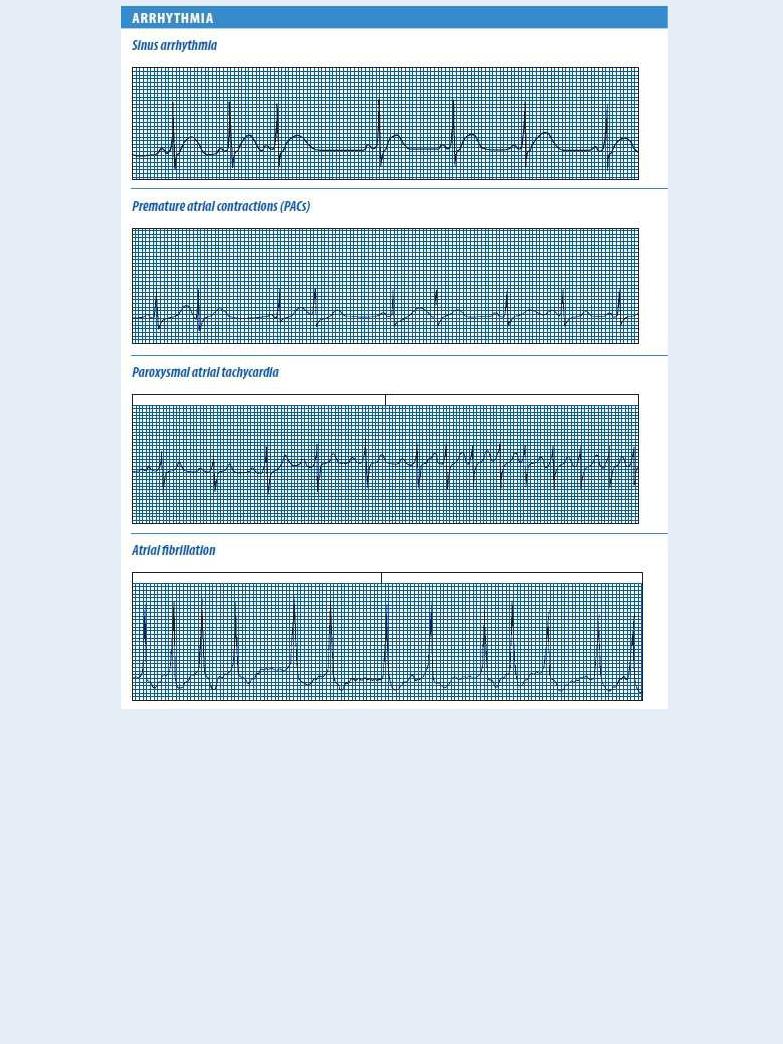

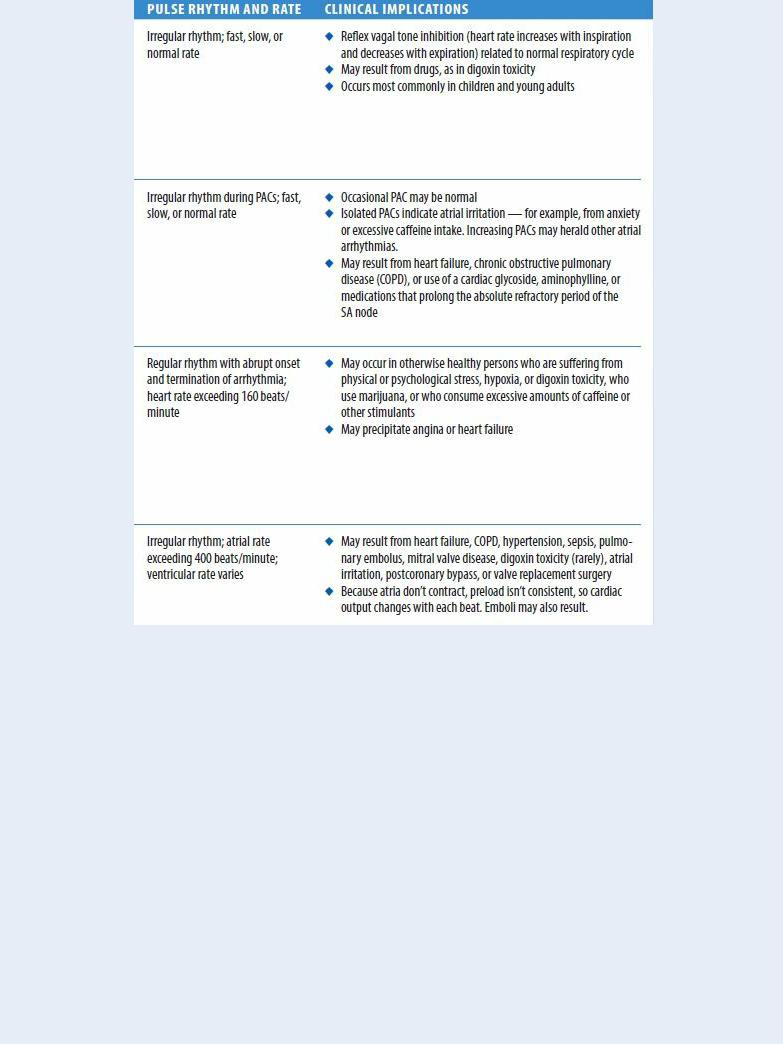

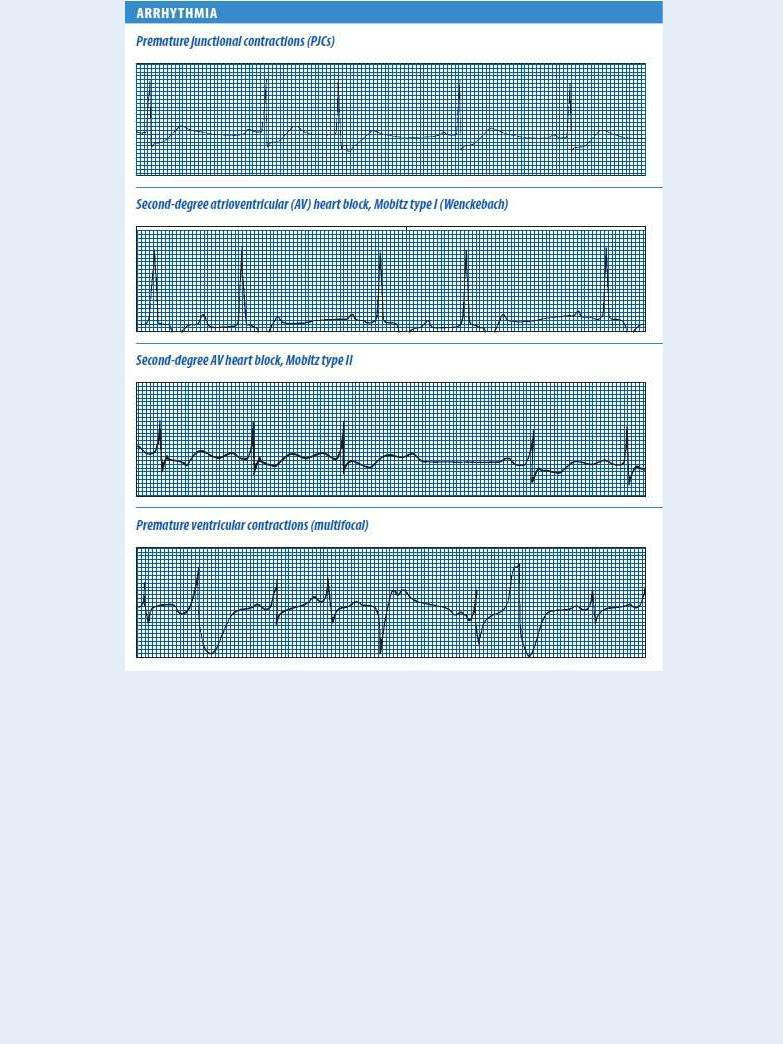

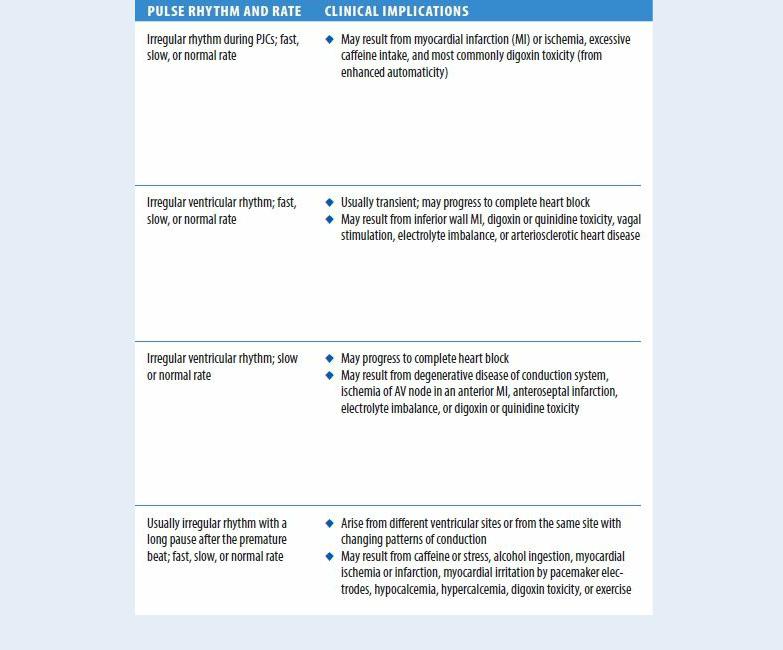

Abnormal Pulse Rhythm: A Clue to Cardiac Arrhythmias

An abnormal pulse rhythm may be your only clue that the patient has a cardiac arrhythmia, but this sign doesn’t help you pinpoint the specific type of arrhythmia. For that, you need a cardiac monitor or an electrocardiogram (ECG) machine. These devices record the electrical current generated by the heart’s conduction system and display this information on an oscilloscope screen or a strip-chart recorder. Besides rhythm disturbances, they can identify conduction defects and electrolyte imbalances.

The ECG strips below show some common cardiac arrhythmias that can cause abnormal pulse rhythms.

Instruct the patient to avoid tobacco and caffeine, both of which increase arrhythmias. If he has a history of failing to comply with prescribed antiarrhythmic therapy, help him develop strategies to overcome this.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms the patient should report. Instruct the patient about taking his pulse, keeping a diary of activities and symptoms, and avoiding tobacco and caffeine.

Pediatric Pointers

Arrhythmias also produce pulse rhythm abnormalities in children.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pulsus Alternans

A sign of severe left-sided heart failure, pulsus alternans (alternating pulse) is a beat-to-beat change in the size and intensity of a peripheral pulse. Although pulse rhythm remains regular, strong and weak contractions alternate. (See Comparing Arterial Pressure Waves , page 608.) An alteration in the intensity of heart sounds and of existing heart murmurs may accompany this sign.

Pulsus alternans is thought to result from the change in stroke volume that occurs with beat-to-beat alteration in the left ventricle’s contractility. Recumbency or exercise increases venous return and reduces the abnormal pulse, which typically disappears with treatment for heart failure. Rarely, a patient with normal left ventricular function has pulsus alternans, but the abnormal pulse seldom persists for more than 10 to 12 beats.

Although most easily detected by sphygmomanometry, pulsus alternans can be detected by palpating the brachial, radial, or femoral artery when systolic pressure varies from beat to beat by more than 20 mm Hg. Because the small changes in arterial pressure that occur during normal respirations may obscure this abnormal pulse, you’ll need to have the patient hold his breath during palpation. Apply light pressure to avoid obliterating the weaker pulse.

When using a sphygmomanometer to detect pulsus alternans, inflate the cuff 10 to 20 mm Hg above the systolic pressure as determined by palpation, and then slowly deflate it. At first, you’ll hear only the strong beats. With further deflation, all beats will become audible and palpable and then equally intense. (The difference between this point and the peak systolic level is commonly used to determine the degree of pulsus alternans.) When the cuff is removed, pulsus alternans returns.

Occasionally, the weak beat is so small that no palpable pulse is detected at the periphery. This produces total pulsus alternans, an apparent halving of the pulse rate.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Pulsus alternans indicates a critical change in the patient’s status. When you detect it, make sure to quickly check his other vital signs. Closely evaluate the patient’s heart rate, respiratory pattern, and blood pressure. Also, auscultate for a ventricular gallop and increased crackles.

Medical Causes

Left-sided heart failure. With left-sided heart failure, pulsus alternans is commonly initiated by a premature beat and is almost always associated with a ventricular gallop. Other findings include hypotension and cyanosis. Possible respiratory findings include exertional and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, orthopnea, tachypnea, Cheyne-Stokes respirations, hemoptysis, and crackles. Fatigue and weakness are common.

Special Considerations

If left-sided heart failure develops suddenly, prepare the patient for pulmonary artery catheter

insertion and transfer to an intensive or cardiac care unit. Meanwhile, elevate the head of his bed to promote respiratory excursion and increase oxygenation. Adjust the patient’s current treatment plan to improve cardiac output, reduce the heart’s workload, and promote diuresis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about left-sided heart failure, his prescribed medications and their possible adverse effects, and recommended lifestyle changes. Stress the importance of follow-up care with a practitioner.

Pediatric Pointers

Pulsus alternans, which also occurs in a child with heart failure, may be difficult to assess if the child is crying or restless. Try to quiet the child by holding him, if his condition permits.

Pulsus Bisferiens

A biferious pulse is a hyperdynamic, double-beating pulse characterized by two systolic peaks separated by a midsystolic dip. Both peaks may be equal or either may be larger; usually, however, the first peak is taller or more forceful than the second. The first peak (percussion wave) is believed to be the pulse pressure and the second (tidal wave), reverberation from the periphery. Pulsus bisferiens occurs in conditions in which a large blood volume is rapidly ejected from the left ventricle, as in aortic insufficiency. The pulse can be palpated in peripheral arteries or observed on an arterial pressure wave recording.

To detect pulsus bisferiens, lightly palpate the carotid, brachial, radial, or femoral artery. (The pulse is easiest to palpate in the carotid artery.) At the same time, listen to the patient’s heart sounds to determine if the two palpable peaks occur during systole. If they do, you’ll feel the double pulse between S1 and S2. (See Comparing Arterial Pressure Waves, page 608.)

History and Physical Examination

After you detect a biferious pulse, review the patient’s history for cardiac disorders. Next, find out what medication he’s taking, if any, and ask if he has other illnesses. Also, ask about the development of associated signs and symptoms, such as dyspnea, chest pain, or fatigue. Find out how long he has had these symptoms and if they change with activity or rest. Then, take his vital signs, and auscultate for abnormal heart or breath sounds.

Medical Causes

Aortic insufficiency. Aortic insufficiency is a heart use of a biferious pulse. Most patients with chronicdefect that’s the most common organic ca aortic insufficiency are asymptomatic until ages 40 to 50. However, exertional dyspnea, worsening fatigue, orthopnea and, eventually, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea may develop.

Acute aortic insufficiency may produce signs and symptoms of left-sided heart failure and cardiovascular collapse, such as weakness, severe dyspnea, hypotension, a ventricular gallop, and tachycardia. Additional findings include chest pain, palpitations, pallor, and strong, abrupt

carotid pulsations. The patient may also exhibit widened pulse pressure and one or more murmurs, especially an apical diastolic rumble (Austin Flint murmur).

High cardiac output states. Pulsus bisferiens commonly occurs with high output states, such as anemia, thyrotoxicosis, a fever, and exercise. Associated findings vary with the underlying cause and may include moderate tachycardia, a cervical venous hum, and widened pulse pressure.

Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. About 40% of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy have pulsus bisferiens because of a pressure gradient in the left ventricular outflow tract. Recorded more often than it’s palpated, the pulse rises rapidly, and the first wave is the more forceful one. Associated findings include a systolic murmur, dyspnea, angina, fatigue, and syncope.

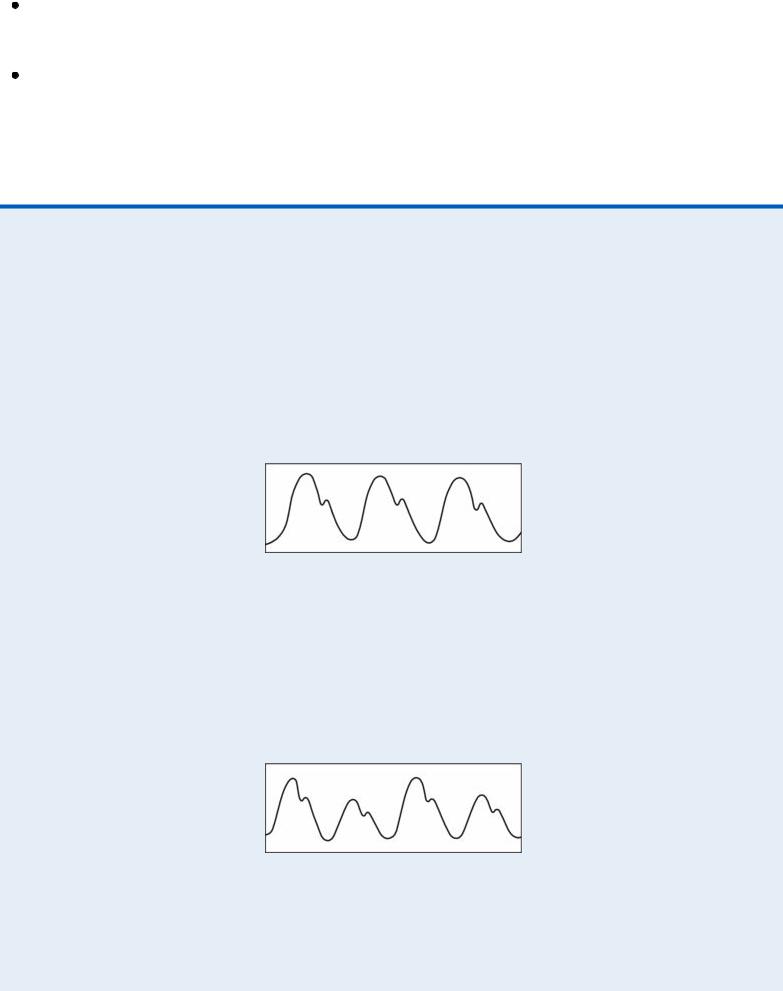

Comparing Arterial Pressure Waves

The waveforms shown here help differentiate a normal arterial pulse from pulsus alternans and pulsus paradoxus.

NORMAL ARTERIAL PULSE

The percussion wave in a normal arterial pulse reflects ejection of blood into the aorta (early systole). The tidal wave is the peak of the pulse wave (later systole), and the dicrotic notch marks the beginning of diastole.

PULSUS ALTERNANS

Pulsus alternans is a beat-to-beat alteration in pulse size and intensity. Although the rhythm of pulsus alternans is regular, the volume varies. If you take the blood pressure of a patient with this abnormality, you’ll first hear a loud Korotkoff sound and then a soft sound, continually alternating. Pulsus alternans commonly accompanies states of poor contractility that occur with left-sided heart failure.

PULSUS BISFERIENS

Pulsus bisferiens is a double-beating pulse with two systolic peaks. The first beat reflects pulse pressure and the second reverberation from the periphery. Pulsus bisferiens commonly occurs with aortic insufficiency (aortic stenosis, aortic regurgitation), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or