Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

them correctly.

Pediatric Pointers

In a child, psychotic behavior may result from early infantile autism, symbiotic infantile psychosis, or childhood schizophrenia — any of which can retard language development, abstract thinking, and socialization. An adolescent patient who exhibits psychotic behavior may have a history of several days’ drug use or lack of sleep or food, which must be evaluated and corrected before therapy can begin.

Reference

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Ptosis

Ptosis is the excessive drooping of one or both upper eyelids. This sign can be constant, progressive, or intermittent and unilateral or bilateral. When it’s unilateral, it’s easy to detect by comparing the eyelids’ relative positions. When it’s bilateral or mild, it’s difficult to detect — the eyelids may be abnormally low, covering the upper part of the iris or even part of the pupil instead of overlapping the iris slightly. Other clues include a furrowed forehead or a tipped-back head — both of these help the patient see under his drooping lids. With severe ptosis, the patient may not be able to raise his eyelids voluntarily. Because ptosis can resemble enophthalmos, exophthalmometry may be required.

Ptosis can be classified as congenital or acquired. Classification is important for proper treatment. Congenital ptosis results from levator muscle underdevelopment or disorders of the third cranial (oculomotor) nerve. Acquired ptosis may result from trauma to or inflammation of these muscles and nerves or from certain drugs, a systemic disease, an intracranial lesion, or a lifethreatening aneurysm. However, the most common cause is advanced age, which reduces muscle elasticity and produces senile ptosis.

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when he first noticed his drooping eyelid. Also, ask him if it has worsened or improved since he first noticed it. Find out if he has recently suffered a traumatic eye injury. (If he has, avoid manipulating the eye to prevent further damage.) Ask about eye pain or headaches, and determine its location and severity. Has the patient experienced vision changes? If so, have him describe them. Obtain a drug history, noting especially the use of a chemotherapeutic drug.

Assess the degree of ptosis, and check for eyelid edema, exophthalmos, deviation, and conjunctival injection. Evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze. Carefully examine the pupils’ size, color, shape, and reaction to light, and test visual acuity.

Keep in mind that ptosis occasionally indicates a life-threatening condition. For example, sudden unilateral ptosis can herald a cerebral aneurysm.

Medical Causes

Botulism. Acute cranial nerve dysfunction as a result of botulism infection causes hallmark

signs of ptosis, dysarthria, dysphagia, and diplopia. Other findings include a dry mouth, a sore throat, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, hyporeflexia, and dyspnea.

Cerebral aneurysm. An aneurysm that compresses the oculomotor nerve can cause sudden ptosis, along with diplopia, a dilated pupil, and an inability to rotate the eye. These may be the first signs of this life-threatening disorder. A ruptured aneurysm typically produces a sudden severe headache, nausea, vomiting, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC). Other findings include nuchal rigidity, back and leg pain, a fever, restlessness, irritability, occasional seizures, blurred vision, hemiparesis, sensory deficits, dysphagia, and visual defects.

Lacrimal gland tumor. A lacrimal gland tumor commonly produces mild to severe ptosis, depending on the tumor’s size and location. It may also cause brow elevation, exophthalmos, eye deviation and, possibly, eye pain.

Myasthenia gravis. Commonly the first sign of myasthenia gravis, gradual bilateral ptosis may be mild to severe and is accompanied by weak eye closure and diplopia. Other characteristics include muscle weakness and fatigue, which eventually may lead to paralysis. Depending on the muscles affected, other findings may include masklike facies, difficulty chewing or swallowing, dyspnea, and cyanosis.

Ocular muscle dystrophy. With ocular muscle dystrophy, bilateral ptosis progresses slowly to complete eyelid closure. Related signs and symptoms include progressive external ophthalmoplegia and muscle weakness and atrophy of the upper face, neck, trunk, and limbs.

Ocular trauma. Trauma to the nerve or muscles that control the eyelids can cause mild to severe ptosis. Depending on the damage, eye pain, lid swelling, ecchymosis, and decreased visual acuity may also occur.

Parry-Romberg syndrome. Unilateral ptosis and facial hemiatrophy occur with Parry-Romberg syndrome. Other signs include miosis, sluggish pupil reaction to light, enophthalmos, differentcolored irises, ocular muscle paralysis, nystagmus, and neck, shoulder, trunk, and extremity atrophy.

Other Causes

Drugs. Vinca alkaloids can produce ptosis.

Lead poisoning. With lead poisoning, ptosis usually develops over 3 to 6 months. Other findings include anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, colicky abdominal pain, a lead line in the gums, a decreased LOC, tachycardia, hypotension and, possibly, irritability and peripheral nerve weakness.

Special Considerations

If the patient has decreased visual acuity, orient him to his surroundings. Provide special spectacle frames that suspend the eyelid by traction with a wire crutch. These frames are usually used to help the patient with temporary paresis or one who isn’t a good candidate for surgery.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic studies, such as the Tensilon test and slit-lamp examination. If he needs surgery to correct levator muscle dysfunction, explain the procedure to him.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the disorder, any required diagnostic tests, and the patient’s treatment

options. Also, discuss self-esteem issues.

Pediatric Pointers

Astigmatism and myopia may be associated with childhood ptosis. Parents typically discover congenital ptosis when their child is an infant. Usually, the ptosis is unilateral, constant, and accompanied by lagophthalmos, which causes the infant to sleep with his eyes open. If this occurs, teach proper eye care to prevent drying.

REFERENCES

Biswas, J. , Krishnakumar, S., & Ahuja, S. (2010) . Manual of ocular pathology. New Delhi, India: Jaypee—Highlights Medical Publishers.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Levin, L. A., & Albert, D. M. (2010). Ocular disease: Mechanisms and management. London, UK: Saunders, Elsevier. Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee—Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

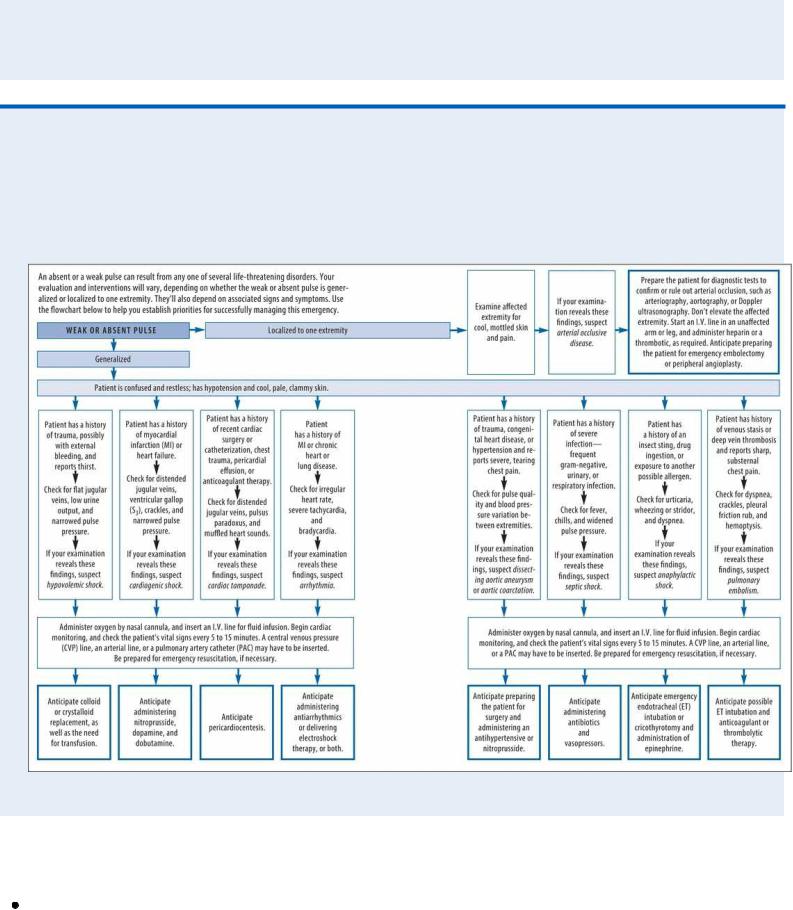

Pulse, Absent or Weak

An absent or a weak pulse may be generalized or affect only one extremity. When generalized, this sign is an important indicator of such life-threatening conditions as shock and arrhythmia. Localized loss or weakness of a pulse that’s normally present and strong may indicate acute arterial occlusion, which could require emergency surgery. However, the pressure of palpation may temporarily diminish or obliterate superficial pulses, such as the posterior tibial or the dorsal pedal. Thus, bilateral weakness or absence of these pulses doesn’t necessarily indicate underlying pathology. (See

Evaluating Peripheral Pulses.)

History and Physical Examination

If you detect an absent or a weak pulse, quickly palpate the remaining arterial pulses to distinguish between localized or generalized loss or weakness. Then, quickly check the patient’s other vital signs, evaluate his cardiopulmonary status, and obtain a brief history. Based on your findings, proceed with emergency interventions. (See Managing an Absent or a Weak Pulse , pages 594 and 595.)

Medical Causes

Aortic aneurysm (dissecting). When a dissecting aneurysm affects circulation to the innominate, left common carotid, subclavian, or femoral artery, it causes weak or absent arterial pulses distal to the affected area. Absent or diminished pulses occur in 50% of patients with proximal dissection and usually involve the brachiocephalic vessels. Pulse deficits are much less common in patients with distal dissection and tend to involve the left subclavian and femoral arteries. Tearing pain usually develops suddenly in the chest and neck and may radiate to the upper and lower back and abdomen. Other findings include syncope, loss of consciousness, weakness or transient paralysis of the legs or arms, the diastolic murmur of aortic insufficiency, systemic hypotension, and mottled skin below the waist.

Aortic arch syndrome (Takayasu’s arteritis). Aortic arch syndrome produces weak or abruptly

absent carotid pulses and unequal or absent radial pulses. These signs are usually preceded by malaise, night sweats, pallor, nausea, anorexia, weight loss, arthralgia, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Other findings include neck, shoulder, and chest pain, paresthesia, intermittent claudication, bruits, vision disturbances, dizziness, and syncope. If the carotid artery is involved, diplopia and transient blindness may occur.

Aortic bifurcation occlusion (acute). Aortic bifurcation occlusion is a rare disorder that produces abrupt absence of all leg pulses. The patient reports moderate to severe pain in the legs and, less commonly, in the abdomen, lumbosacral area, or perineum. Also, his legs are cold, pale, numb, and flaccid.

Aortic stenosis. With aortic stenosis, the carotid pulse is sustained but weak. Dyspnea (especially on exertion or paroxysmal nocturnal), chest pain, and syncope dominate the clinical picture. The patient commonly has an atrial gallop. Other findings include a harsh systolic ejection murmur, crackles, palpitations, fatigue, and narrowed pulse pressure.

Arrhythmias. Cardiac arrhythmias may produce generalized weak pulses accompanied by cool, clammy skin. Other findings reflect the arrhythmia’s severity and may include hypotension, chest pain, dyspnea, dizziness, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC).

Arterial occlusion. With acute occlusion, arterial pulses distal to the obstruction are unilaterally weak and then absent. The affected limb is cool, pale, and cyanotic, with an increased capillary refill time, and the patient complains of moderate to severe pain and paresthesia. A line of color and temperature demarcation develops at the level of obstruction. Varying degrees of limb paralysis may also occur, along with intense intermittent claudication. With chronic occlusion, occurring with disorders such as arteriosclerosis and Buerger’s disease, pulses in the affected limb weaken gradually.

Cardiac tamponade. Life-threatening cardiac tamponade causes a weak, rapid pulse accompanied by these classic findings: paradoxical pulse, jugular vein distention, hypotension, and muffled heart sounds. Narrowed pulse pressure, pericardial friction rub, and hepatomegaly may also occur. The patient may appear anxious, restless, and cyanotic and may have chest pain, clammy skin, dyspnea, and tachypnea.

Coarctation of the aorta. Findings of coarctation of the aorta include bounding pulses in the arms and neck, with decreased pulsations and systolic pulse pressure in the lower extremities. Peripheral vascular disease. Peripheral vascular disease causes a weakening and loss of peripheral pulses. The patient complains of aching pain distal to the occlusion that worsens with exercise and abates with rest. The skin feels cool and shows decreased hair growth. Impotence may occur in male patients with occlusion in the descending aorta or femoral areas.

Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism causes a generalized weak, rapid pulse. It may also cause an abrupt onset of chest pain, tachycardia, dyspnea, apprehension, syncope, diaphoresis, and cyanosis. Acute respiratory findings include tachypnea, dyspnea, decreased breath sounds, crackles, a pleural friction rub, and a cough — possibly with blood-tinged sputum.

Shock. With anaphylactic shock, pulses become rapid and weak and then uniformly absent within seconds or minutes after exposure to an allergen. This is preceded by hypotension, anxiety, restlessness, feelings of doom, intense itching, a pounding headache and, possibly, urticaria.

With cardiogenic shock, peripheral pulses are absent and central pulses are weak, depending on the degree of vascular collapse. Pulse pressure is narrow. A drop in systolic blood pressure to 30 mm Hg below baseline, or a sustained reading below 80 mm Hg, produces poor tissue

perfusion. Resulting signs include cold, pale, clammy skin; tachycardia; rapid, shallow respirations; oliguria; restlessness; confusion; and obtundation.

With hypovolemic shock, all pulses in the extremities become weak and then uniformly absent, depending on the severity of hypovolemia. As shock progresses, remaining pulses become thready and more rapid. Early signs of cardiogenic shock include restlessness, thirst, tachypnea, and cool, pale skin. Late signs include hypotension with narrowing pulse pressure, clammy skin, a drop in urine output to less than 25 mL/hour, confusion, a decreased LOC and, possibly, hypothermia.

With septic shock, all pulses in the extremities first become weak. Depending on the degree of vascular collapse, pulses may then become uniformly absent. Shock is heralded by chills, a sudden fever and, possibly, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Typically, the patient experiences tachycardia, tachypnea, and flushed, warm, and dry skin. As shock progresses, he develops thirst, hypotension, anxiety, restlessness, and confusion. Then, pulse pressure narrows and the skin becomes cold, clammy, and cyanotic. The patient experiences severe hypotension, oliguria or anuria, respiratory failure, and coma.

Thoracic outlet syndrome. A patient with thoracic outlet syndrome may develop gradual or abrupt weakness or loss of the pulses in the arms, depending on how quickly vessels in the neck compress. These pulse changes commonly occur after the patient works with his hands above his shoulders, lifts a weight, or abducts his arm. Paresthesia and pain occur along the ulnar distribution of the arm and disappear as soon as the patient returns his arm to a neutral position. The patient may also have asymmetrical blood pressure and cool, pale skin.

Evaluating Peripheral Pulses

The rate, amplitude, and symmetry of peripheral pulses provide important clues to cardiac function and the quality of peripheral perfusion. To gather these clues, palpate peripheral pulses lightly with the pads of your index, middle, and ring fingers, as space permits.

RATE

Count all pulses for at least 30 seconds (60 seconds when recording vital signs). The normal rate is between 60 and 100 beats/minute.

AMPLITUDE

Palpate the blood vessel during ventricular systole. Describe pulse amplitude by using a scale such as the one below:

4+ = bounding

3+ = increased

2+ = normal

1+ = weak, thready

0 = absent

Use a stick figure to easily document the location and amplitude of all pulses.

SYMMETRY

Simultaneously palpate pulses (except for the carotid pulse) on both sides of the patient’s body, and note inequality. Always assess peripheral pulses methodically, moving from the arms to the legs.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Managing an Absent or a Weak Pulse

Other Causes

Treatments. Localized absent pulse may occur distal to arteriovenous shunts for dialysis.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs to detect untoward changes in his condition. Monitor hemodynamic status by measuring daily weight and hourly or daily intake and output and by assessing central venous pressure.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient techniques for checking his pulse, and explain which signs and symptoms to report. Discuss food and fluid restrictions and the need to avoid activities that reduce circulation.

Pediatric Pointers

Radial, dorsal pedal, and posterior tibial pulses aren’t easily palpable in infants and small children, so be careful not to mistake these normally hard-to-find pulses for weak or absent pulses. Instead, palpate the brachial, popliteal, or femoral pulses to evaluate arterial circulation to the extremities. In children and young adults, weak or absent femoral and more distal pulses may indicate coarctation of the aorta.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pulse, Bounding

Produced by large waves of pressure as blood ejects from the left ventricle with each contraction, a bounding pulse is strong and easily palpable and may be visible over superficial peripheral arteries. It’s characterized by regular, recurrent expansion and contraction of the arterial walls and isn’t obliterated by the pressure of palpation. A healthy person develops a bounding pulse during exercise, pregnancy, and periods of anxiety. However, this sign also results from a fever and certain endocrine, hematologic, and cardiovascular disorders that increase the basal metabolic rate.

History and Physical Examination

After you detect a bounding pulse, check the patient’s other vital signs, and then, auscultate the heart and lungs for abnormal sounds, rates, or rhythms. Ask the patient if he has noticed weakness, fatigue, shortness of breath, or other health changes. Review his medical history for hyperthyroidism, anemia, or a cardiovascular disorder, and ask about his use of alcohol.

Medical Causes

Alcoholism (acute). Vasodilation produces a rapid, bounding pulse and flushed face. An odor of alcohol on the breath and an ataxic gait are common. Other findings include hypothermia, bradypnea, labored and loud respirations, nausea, vomiting, diuresis, a decreased level of consciousness, and seizures.

Aortic insufficiency. Sometimes called a water-hammer pulse, the bounding pulse associated with aortic insufficiency is characterized by rapid, forceful expansion of the arterial pulse followed by rapid contraction. Widened pulse pressure also occurs. This disorder may produce findings associated with left-sided heart failure and cardiovascular collapse, such as weakness,

severe dyspnea, hypotension, an S3, and tachycardia. Additional findings include pallor, chest pain, palpitations, or strong, abrupt carotid pulsations. The patient may also experience pulsus bisferiens, an early systolic murmur, a murmur heard over the femoral artery during systole and diastole, and a high-pitched diastolic murmur that starts with the second heart sound. An apical diastolic rumble (Austin Flint murmur) may also occur, especially with heart failure. Most patients with chronic aortic insufficiency remain asymptomatic until their 40s or 50s, when exertional dyspnea, increased fatigue, orthopnea and, eventually, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, angina, and syncope may develop.

Febrile disorder. A fever can cause a bounding pulse. Accompanying findings reflect the specific disorder.

Thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis produces a rapid, full, bounding pulse. Associated findings include tachycardia, palpitations, an S3 or S4 gallop, weight loss despite increased appetite, and heat intolerance. The patient may also develop diarrhea, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, tremors, nervousness, chest pain, exophthalmos, and signs of cardiovascular collapse. His skin will be warm, moist, and diaphoretic, and he may be hypersensitive to heat.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic laboratory and radiographic studies. If a bounding pulse is accompanied by a rapid or an irregular heartbeat, you may need to connect the patient to a cardiac monitor for further evaluation.

Patient Counseling

Discuss dietary modifications and fluid restrictions the patient needs. Emphasize the importance of avoiding alcohol, and refer the patient to Alcoholics Anonymous, as needed. Stress the importance of rest periods, and explain which signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

A bounding pulse can be normal in infants or children because arteries lie close to the skin surface. It can also result from patent ductus arteriosus if the left-to-right shunt is large.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pulse Pressure, Narrowed

Pulse pressure, the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressures, is measured by sphygmomanometry or intra-arterial monitoring. Normally, systolic pressure exceeds diastolic by about 40 mm Hg. Narrowed pressure — a difference of less than 30 mm Hg — occurs when peripheral vascular resistance increases, cardiac output declines, or intravascular volume markedly decreases.

With conditions that cause mechanical obstruction, such as aortic stenosis, pulse pressure is directly related to the severity of the underlying condition. Usually a late sign, narrowed pulse pressure alone doesn’t signal an emergency, even though it commonly occurs with shock and other life-threatening disorders.

History and Physical Examination

After you detect a narrowed pulse pressure, check for other signs of heart failure, such as hypotension, tachycardia, dyspnea, jugular vein distention, pulmonary crackles, and decreased urine output. Also, check for changes in skin temperature or color, the strength of peripheral pulses, and the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Auscultate the heart for murmurs. Ask about a history of chest pain, dizziness, or syncope.

Medical Causes

Cardiac tamponade. With cardiac tamponade, a life-threatening disorder, pulse pressure narrows by 10 to 20 mm Hg. Paradoxical pulse, jugular vein distention, hypotension, and muffled heart sounds are classic. The patient may be anxious, restless, and cyanotic, with clammy skin and chest pain. He may exhibit dyspnea, tachypnea, a decreased LOC, and a weak, rapid pulse. A pericardial friction rub and hepatomegaly may also occur.

Heart failure. Narrowed pulse pressure occurs relatively late and may accompany tachypnea, palpitations, dependent edema, steady weight gain despite nausea and anorexia, chest tightness, slowed mental response, hypotension, diaphoresis, pallor, and oliguria. Assessment reveals a ventricular gallop, inspiratory crackles and, possibly, a tender, palpable liver. Later, dullness develops over the lung bases, and hemoptysis, cyanosis, marked hepatomegaly, and marked pitting edema may occur.

Shock. With anaphylactic shock, narrowed pulse pressure occurs late, preceded by a rapid, weak pulse that soon becomes uniformly absent. Within seconds or minutes after exposure to an allergen, the patient experiences hypotension, anxiety, restlessness, and feelings of doom, along with intense itching, a pounding headache and, possibly, urticaria. Other findings include dyspnea, stridor, and hoarseness; chest or throat tightness; skin flushing; nausea, abdominal cramps, and urinary incontinence; and seizures.

With cardiogenic shock, narrowed pulse pressure occurs relatively late. Typically, peripheral pulses are absent and central pulses are weak. A drop in systolic pressure to 30 mm Hg below baseline, or a sustained reading below 80 mm Hg not attributable to medication, produces poor tissue perfusion. Poor perfusion produces tachycardia; tachypnea; cold, pale, clammy skin; cyanosis; oliguria; restlessness; confusion; and obtundation.

With hypovolemic shock, narrowed pulse pressure occurs as a late sign. All peripheral pulses become first weak and then uniformly absent. Deepening shock leads to hypotension, urine output of less than 25 mL/hour, confusion, a decreased LOC and, possibly, hypothermia.

With septic shock, narrowed pulse pressure is a relatively late sign. All peripheral pulses become first weak and then uniformly absent. As shock progresses, the patient exhibits oliguria, thirst, anxiety, restlessness, confusion, and hypotension. Extremities become cool and cyanotic; the skin becomes cold and clammy. In time, he develops severe hypotension, persistent oliguria or anuria, respiratory failure, and coma.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient closely for changes in the pulse rate or quality and for hypotension or a diminished LOC. Prepare him for diagnostic studies, such as echocardiography, to detect valvular heart disease or cardiac tamponade secondary to a pericardial effusion.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disorder and treatments and which foods and fluids the patient should avoid. Stress the importance of rest periods to reduce fatigue.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, narrowed pulse pressure can result from congenital aortic stenosis as well as from disorders that affect adults.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pulse Pressure, Widened

Pulse pressure is the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressures. Normally, systolic pressure is about 40 mm Hg higher than diastolic pressure. Widened pulse pressure — a difference of more than 50 mm Hg — commonly occurs as a physiologic response to a fever, hot weather, exercise, anxiety, anemia, or pregnancy. However, it can also result from certain neurologic disorders — especially life-threatening increased intracranial pressure (ICP) — or from cardiovascular disorders that cause blood backflow into the heart with each contraction such as aortic insufficiency. Widened pulse pressure can easily be identified by monitoring arterial blood pressure and is commonly detected during routine sphygmomanometric recordings.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) is decreased, and you suspect that his widened pulse pressure results from increased ICP, check his vital signs. Maintain a patent airway, and prepare to hyperventilate the patient with a handheld resuscitation bag to help reduce partial pressure of carbon dioxide levels and, thus, ICP. Perform a thorough neurologic examination to serve as a baseline for assessing subsequent changes. Use the Glasgow Coma Scale to evaluate the patient’s LOC. (See Glasgow Coma Scale, page 439.) Also, check cranial nerve function — especially in cranial nerves III, IV, and VI — and assess pupillary reactions, reflexes, and muscle tone. Insertion of an ICP monitor may be necessary. If you don’t suspect increased ICP, ask about associated symptoms, such as chest pain, shortness of breath, weakness, fatigue, or syncope. Check for edema, and auscultate for murmurs.