Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

include contralateral hemiplegia, seizures, a headache, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, apraxia, and agnosia. Visual deficits include homonymous hemianopsia, blurring, decreased acuity, and diplopia. Urine retention or incontinence, fecal incontinence, constipation, and vomiting may also occur.

Other Causes

Drugs. Priapism can result from the use of a phenothiazine, thioridazine, trazodone, an androgenic steroid, an anticoagulant, or an antihypertensive. It may also occur after an intracorporeal injection of papaverine, a common treatment for impotence.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for blood tests to help determine the cause of priapism. If he requires surgery, keep his penis flaccid postoperatively by applying a pressure dressing. At least once every 30 minutes, inspect the glans for signs of vascular compromise, such as coolness or pallor.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying condition and treatment. Make sure the patient with sickle cell anemia knows to report episodes of priapism.

Pediatric Pointers

In neonates, priapism can result from hypoxia, but is usually resolved with oxygen therapy. Priapism is more likely to develop in children with sickle cell disease than in adults with the disease.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Pruritus

Commonly provoking scratching to gain relief, this unpleasant itching sensation affects the skin, certain mucous membranes, and the eyes. Most severe at night, pruritus may be exacerbated by increased skin temperature, poor skin turgor, local vasodilation, dermatoses, and stress.

The most common symptom of dermatologic disorders, pruritus may also result from a local or systemic disorder or from drug use. Physiologic pruritus, such as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, may occur in primigravidas late in the third trimester. Pruritus can also stem from emotional upset or contact with skin irritants.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports pruritus, have him describe its onset, frequency, and intensity. If pruritus occurs at night, ask whether it prevents him from falling asleep or awakens him after he falls asleep.

(Generally, pruritus related to dermatoses prevents — but doesn’t disturb — sleep.) Is the itching localized or generalized? When is it most severe? How long does it last? Is there a relationship to activities (physical exertion, bathing, applying makeup, or the use of perfumes)?

Ask the patient how he cleans his skin. In particular, look for excessive bathing, harsh soaps, contact allergy, and excessively hot water. Does he have occupational exposure to known skin irritants, such as glass fiber insulation or chemicals? Ask about the patient’s general health and the medications he takes (new medications are suspect). Has he recently traveled abroad? Does he have pets? Does anyone else in the house report itching? Does exercise, stress, fear, depression, or illness seem to aggravate the itching? Ask about contact with skin irritants, previous skin disorders, and related symptoms. Then, obtain a complete drug history.

Examine the patient for signs of scratching, such as excoriation, purpura, scabs, scars, or lichenification. Look for primary lesions to help confirm dermatoses.

Medical Causes

Anemia (iron deficiency). Iron deficiency anemia occasionally produces pruritus. Initially asymptomatic, anemia can later cause exertional dyspnea, fatigue, listlessness, pallor, irritability, a headache, tachycardia, poor muscle tone and, possibly, murmurs. Chronic anemia causes spoon-shaped (koilonychia) and brittle nails (cheilosis), cracked mouth corners, a smooth tongue (glossitis), and dysphagia.

Anthrax (cutaneous). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. It can occur in humans who are exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Cutaneous anthrax occurs when the bacterium enters a cut or an abrasion on the skin. The infection begins as a small, painless or pruritic macular or papular lesion resembling an insect bite. Within 1 to 2 days, it develops into a vesicle and then a painless ulcer with a characteristic black, necrotic center. Lymphadenopathy, malaise, a headache, or a fever may develop.

Conjunctivitis. All forms of conjunctivitis cause eye itching, burning, and pain along with photophobia, conjunctival injection, a foreign body sensation, excessive tearing, and a feeling of fullness around the eye. Allergic conjunctivitis may also cause milky redness and a stringy eye discharge. Bacterial conjunctivitis typically causes brilliant redness and a mucopurulent discharge that may make the eyelids stick together. Fungal conjunctivitis produces a thick, purulent discharge and crusting and sticking of the eyelid. Viral conjunctivitis may cause copious tearing — but little discharge — and preauricular lymph node enlargement.

Dermatitis. Several types of dermatitis can cause pruritus accompanied by a skin lesion. Atopic dermatitis begins with intense, severe pruritus and an erythematous rash on dry skin at flexion points (antecubital fossa, popliteal area, and neck). During a flareup, scratching may produce edema, scaling, and pustules. With chronic atopic dermatitis, lesions may progress to dry, scaly skin with white dermatographia, blanching, and lichenification.

Mild irritants and allergies can cause contact dermatitis, with itchy small vesicles that may ooze and scale and are surrounded by redness. A severe reaction can produce marked localized edema.

Dermatitis herpetiformis, most common in men between ages 20 and 50, initially causes intense pruritus and stinging. Between 8 and 12 hours later, symmetrically distributed lesions form on the buttocks, shoulders, elbows, and knees. Sometimes, they also form on the neck, face, and

scalp. These lesions are erythematous and papular, bullous, or pustular.

Hepatobiliary disease. An important diagnostic clue to liver and gallbladder disease, pruritus is commonly accompanied by jaundice and may be generalized or localized to the palms and soles. Other characteristics include right upper quadrant pain, clay-colored stools, chills and a fever, flatus, belching and a bloated feeling, epigastric burning, and bitter fluid regurgitation. Later, liver disease may produce mental changes, ascites, bleeding tendencies, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, dry skin, fetor hepaticus, enlarged superficial abdominal veins, bilateral gynecomastia, testicular atrophy or menstrual irregularities, and hepatomegaly.

Herpes zoster. Within 2 to 4 days of a fever and malaise, pruritus, paresthesia or hyperesthesia, and severe, deep pain from cutaneous nerve involvement develop on the trunk or the arms and legs in a dermatome distribution. Up to 2 weeks after initial symptoms, red, nodular skin eruptions appear on the painful areas and become vesicular. About 10 days later, the vesicles rupture and form scabs.

Leukemia (chronic lymphocytic). Pruritus is an uncommon finding in leukemia. More characteristic signs and symptoms include fatigue, malaise, generalized lymphadenopathy, a fever, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, weight loss, pallor, bleeding, and palpitations.

Lichen simplex chronicus. Persistent rubbing and scratching cause localized pruritus and a circumscribed scaling patch with sharp margins. Later, the skin thickens and papules form. Myringitis (chronic). Myringitis produces pruritus in the affected ear, along with a purulent discharge and gradual hearing loss.

Pediculosis. A prominent symptom, pruritus occurs in the area of infestation. Pediculosis capitis (head lice) may also cause scalp excoriation from scratching, along with matted, foul-smelling, lusterless hair; occipital and cervical lymphadenopathy; and oval, gray-white nits on hair shafts. Pediculosis corporis (body lice) initially causes small red papules (usually on the shoulders, trunk, or buttocks), which become urticarial from scratching. Later, rashes or wheals may develop. Untreated, pediculosis corporis produces dry, discolored, thickly encrusted, scaly skin with bacterial infection and scarring. In severe cases, it produces a headache, a fever, and malaise.

With pediculosis pubis (pubic lice), scratching commonly produces skin irritation. Nits or adult lice and erythematous, itching papules may appear in pubic hair or in hair around the anus, abdomen, or thighs.

Pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea occasionally produces mild pruritus that’s aggravated by a hot bath or shower. It usually begins with an erythematous herald patch — a slightly raised, oval lesion about 2 to 6 cm in diameter. After a few days or weeks, scaly yellow-tan or erythematous patches erupt on the trunk and extremities and persist for 2 to 6 weeks. Occasionally, these patches are macular, vesicular, or urticarial.

Psoriasis. Pruritus and pain are common in psoriasis. This skin disorder typically begins with small erythematous papules that enlarge or coalesce to form red elevated plaques with silver scales on the scalp, chest, elbows, knees, back, buttocks, and genitals. Nail pitting may occur.

Scabies. Typically, scabies causes localized pruritus that awakens the patient. It may become generalized and persist for up to 2 weeks after treatment. Threadlike lesions several millimeters long appear with a swollen nodule or red papule.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

In males, crusty lesions may form on the glans penis, penile shaft, and scrotum. In females, lesions may also be found on or around the nipples. In both sexes, the lesions have a predilection for skin folds. Crusty excoriated lesions form on the wrists, elbows, axillae, waistline, behind the knees, and ankles. Excoriation from scratching is common.

Tinea pedis. Tinea pedis is a fungal infection that causes severe foot pruritus, pain with walking, scales and blisters between the toes, and a dry, scaly squamous inflammation on the entire sole.

Urticaria. Extreme pruritus and stinging occur as transient, erythematous or whitish wheals form on the skin or mucous membranes. Prickly sensations typically precede the wheals, which may affect any part of the body and may range from pinpoint to palm sized or larger.

Vaginitis. Vaginitis commonly causes localized pruritus and a foul-smelling vaginal discharge that may be purulent, white or gray, and curdlike. Perineal pain and urinary dysfunction may also occur.

Other Causes

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Ingestion of fruit pulp from the ginkgo tree can cause rapid formation of vesicles, resulting in severe itching.

Bedbug bites. Typically, bedbug bites produce itching and burning over the ankles and lower legs, along with clusters of purpuric spots.

Drug hypersensitivity. When mild and localized, an allergic reaction to such drugs as penicillin and sulfonamides can cause pruritus, erythema, an urticarial rash, and edema. However, with a severe drug reaction, anaphylaxis may occur.

Special Considerations

Administer a topical or oral corticosteroid, an antihistamine, or a tranquilizer, as ordered. If the patient doesn’t have a localized infection or skin lesions, suspect a systemic disease and prepare him for a complete blood count and differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, protein electrophoresis, and radiologic studies.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient ways to control pruritus. Reinforce the importance of not scratching.

Pediatric Pointers

Many adult disorders also cause pruritus in children, but they may affect different parts of the body. For instance, scabies may affect the head in infants, but not in adults. Pityriasis rosea may affect the

face, hands, and feet of adolescents.

Some childhood diseases, such as measles and chickenpox, can cause pruritus.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Psoas Sign

A positive psoas sign — increased abdominal pain when the patient moves his leg against resistance

— indicates direct or reflexive irritation of the psoas muscles. This sign, which can be elicited on the right or left side, usually indicates appendicitis, but may also occur with localized abscesses. It’s elicited in a patient with abdominal or lower back pain after completion of an abdominal examination to prevent spurious assessment findings. (See Eliciting a Psoas Sign.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you elicit a positive psoas sign in a patient with abdominal pain, suspect appendicitis. Quickly check the patient’s vital signs, and prepare him for surgery: Explain the procedure, restrict food and fluids, and withhold analgesics, which can mask symptoms. Administer I.V. fluids to prevent dehydration, but don’t give a cathartic or an enema, because it can cause a ruptured appendix and lead to peritonitis.

Check for Rovsing’s sign by deeply palpating the patient’s left lower quadrant. If he reports pain in the right lower quadrant, the sign is positive, indicating peritoneal irritation.

Medical Causes

Appendicitis. An inflamed retrocecal appendix can cause a positive right psoas sign. Early epigastric and periumbilical pain disappears, only to worsen and localize in the right lower quadrant. This pain also worsens with walking or coughing. Related findings include nausea and vomiting, abdominal rigidity and rebound tenderness, and constipation or diarrhea. A fever, tachycardia, retractive respirations, anorexia, and malaise may also occur. If the appendix ruptures, additional findings may include sudden, severe pain, followed by signs of peritonitis, such as hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, a high fever, and boardlike abdominal rigidity. A positive obturator sign may also be evident.

Retroperitoneal abscess. After a lower retroperitoneal infection, an iliac or lumbar abscess can produce a positive right or left psoas sign and a fever. An iliac abscess causes iliac or inguinal

pain that may radiate to the hip, thigh, flank, or knee; a tender mass in the lower abdomen or groin may be palpable. A lumbar abscess usually produces back tenderness and spasms on the affected side with a palpable lumbar mass; a tender abdominal mass without back pain may occur instead.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s vital signs to detect complications, such as pain extension along fascial planes in the abdomen, thigh, hip, subphrenic spaces, mediastinum, and pleural cavities, and peritonitis. Promote patient comfort by helping with position changes. For example, have the patient lie down and flex his right leg. Then, have him sit upright.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as electrolyte studies and abdominal X-rays.

Pediatric Pointers

Elicit a psoas sign by asking the child to raise his head while you exert pressure on his forehead. Resulting right lower quadrant pain usually indicates appendicitis.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about the underlying cause of his condition and its treatments. Discuss signs and symptoms that require immediate attention, and teach the patient how to report pain using a pain rating scale.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, the psoas sign and other peritoneal signs may be decreased or absent. Make sure to differentiate pain elicited through psoas maneuvers from musculoskeletal or degenerative joint pain.

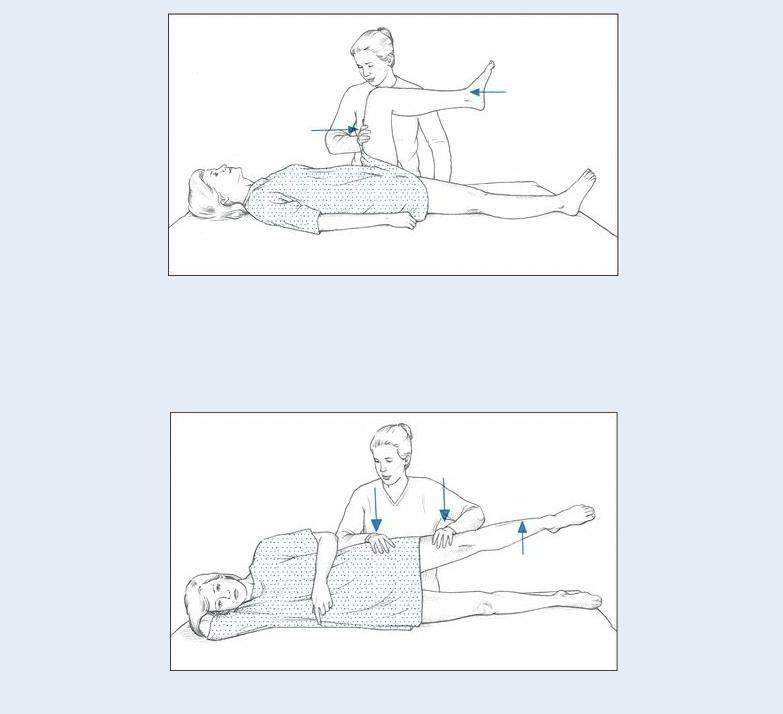

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting a Psoas Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting a Psoas Sign

You can use two techniques to elicit a psoas sign in an adult with abdominal pain. With either technique, increased abdominal pain is a positive result, indicating psoas muscle irritation from an inflamed appendix or a localized abscess.

With the patient in a supine position, instruct her to move her flexed left leg against your hand to test for a left psoas sign. Then, perform this maneuver on the right leg to test for a right psoas sign.

To test for a left psoas sign, turn the patient onto her right side. Then, instruct her to push her left leg upward from the hip against your hand. Next, turn the patient onto her left side, and repeat this maneuver to test for a right psoas sign.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, MO: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Psychotic Behavior

Psychotic behavior reflects an inability or unwillingness to recognize and acknowledge reality and to relate with others. It may begin suddenly or insidiously, progressing from vague complaints of fatigue, insomnia, or headaches to withdrawal, social isolation, and preoccupation with certain issues,

resulting in gross impairment in functioning.

Various behaviors together or separately can constitute psychotic behavior. These include delusions, illusions, hallucinations, bizarre language, and perseveration. Delusions are persistent beliefs that have no basis in reality or in the patient’s knowledge or experience such as delusions of grandeur. Illusions are misinterpretations of external sensory stimuli such as a mirage in the desert. In contrast, hallucinations are sensory perceptions that don’t result from external stimuli. Bizarre language reflects a communication disruption. It can range from echolalia (purposeless repetition of a word or phrase) and clang association (repetition of words or phrases that sound similar) to neologisms (creation and use of words whose meaning only the patient knows). Perseveration, a persistent verbal or motor response, may indicate organic brain disease. Motor changes include inactivity, excessive activity, and repetitive movements.

History and Physical Examination

Because the patient’s behavior can make it difficult — or potentially dangerous — to obtain pertinent information, conduct the interview in a calm, safe, and well-lit room. Provide enough personal space to avoid threatening or agitating the patient. Ask him to describe his problem and circumstances that may have precipitated it. Obtain a drug history, noting especially the use of an antipsychotic, and explore his use of alcohol and other drugs, such as cocaine, indicating duration of use and amount. Ask about recent illnesses or accidents.

As the patient talks, watch for cognitive, linguistic, or perceptual abnormalities such as delusions. Do thoughts and actions seem to match? Look for unusual gestures, posture, gait, tone of voice, and mannerisms. Does the patient appear to be responding to stimuli? For example, is he looking around the room?

Interview the patient’s family. Which family members does he seem closest to? How does the family describe the patient’s relationships, communication patterns, and role? Has a family member ever been hospitalized for psychiatric or emotional illness? Ask about the patient’s compliance with his drug regimen.

Finally, evaluate the patient’s environment, educational and employment history, and socioeconomic status. Are community services available? How does the patient spend his leisure time? Does he have friends? Has he ever had a close emotional relationship?

Medical Causes

Organic disorders. Various organic disorders, such as alcohol withdrawal syndrome, cocaine or amphetamine intoxication, cerebral hypoxia, and nutritional disorders, can produce psychotic behavior. Endocrine disorders, such as adrenal dysfunction, and severe infections, such as encephalitis, can also cause psychotic behavior. Neurologic causes include Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Psychiatric disorders. Psychotic behavior usually occurs with bipolar disorder, personality disorder, schizophrenia, and some pervasive developmental disorders.

Psychotic Behavior: An Adverse Drug Effect

Certain drugs can cause psychotic behavior and other psychiatric signs and symptoms, ranging

from depression to violent behavior. Usually, these effects occur during therapy and resolve when the drug is discontinued. If the patient is receiving one of these common drugs and exhibits the behavior described, the dosage may have to be changed or another drug may have to be substituted.

Controlling Psychotic Behavior

A patient who displays psychotic behavior may be terrified and unable to differentiate between

himself and his environment. To control his behavior and to prevent injury to the patient, staff, and others, follow these guidelines.

Remove potentially dangerous objects, such as belts or metal utensils, from the patient’s environment.

Help the patient discern what’s real and unreal in an honest and genuine way.

Be straightforward, concise, and nonthreatening when speaking to the patient. Discuss simple, concrete subjects and avoid theories or philosophical issues.

Positively reinforce the patient’s perceptions of reality, and correct his misperceptions in a matter-of-fact way.

Never argue with the patient, but also don’t support his misperceptions. If the patient is frightened, stay with him.

Touch the patient to provide reassurance only if you’ve done this before and know that it’s safe.

Move the patient to a safer, less stimulating environment.

Provide one-on-one care if the patient’s behavior is extremely bizarre, disturbing to other patients, or dangerous to himself.

Medicate the patient appropriately.

Other Causes

Drugs. Certain drugs can cause psychotic behavior. (See Psychotic Behavior: An Adverse Drug Effect.) However, almost any drug can provoke psychotic behavior as a rare, severe adverse or idiosyncratic reaction.

Surgery. Postoperative delirium and depression may produce psychotic behavior.

Special Considerations

Continuously evaluate the patient’s orientation to reality. Help him develop a conception of reality by calling him by his preferred name, telling him your name, describing where he is, and using clocks and calendars. (See Controlling Psychotic Behavior, page 590.)

Encourage the patient to become involved in structured activities. However, if he’s nonverbal or incoherent, make sure to spend time with him. For example, sit or walk with him or talk about the day, the season, the weather, or other concrete topics. Avoid making time commitments that you can’t keep: This will only upset the patient and cause him to withdraw more.

Refer the patient for psychiatric evaluation. Administer an antipsychotic or other drugs, as needed, and prepare him for transfer to a mental health center, if necessary.

Don’t overlook the patient’s physiologic needs. Check his eating habits to avoid dehydration and malnutrition, and monitor his elimination patterns, especially if he’s receiving an antipsychotic, which can cause constipation.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of structured activities, and discuss the patient’s medications and how to take