Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

Because pain is subjective and is exacerbated by anxiety, patients who are highly emotional may complain more readily of pleuritic pain than those who are habitually stoic about symptoms of illness.

Ask the patient about a history of rheumatoid arthritis, a respiratory or cardiovascular disorder, recent trauma, asbestos exposure, or radiation therapy. If he smokes, obtain a history in pack-years.

Characterize the pleural friction rub by auscultating the lungs with the patient sitting upright and breathing deeply and slowly through his mouth. Is the friction rub unilateral or bilateral? Also, listen for absent or diminished breath sounds, noting their location and timing in the respiratory cycle. Do abnormal breath sounds clear with coughing? Observe the patient for clubbing and pedal edema, which may indicate a chronic disorder. Then, palpate for decreased chest motion, and percuss for flatness or dullness.

Medical Causes

Asbestosis. Besides a pleural friction rub, asbestosis may cause exertional dyspnea, cough, chest pain, and crackles. Clubbing is a late sign.

Lung cancer. A pleural friction rub may be heard in the affected area of the lung. Other effects include a cough (with possible hemoptysis), dyspnea, chest pain, weight loss, anorexia, fatigue, clubbing, a fever, and wheezing.

Pleurisy. A pleural friction rub occurs early in pleurisy. However, the cardinal symptom is sudden, intense chest pain that’s usually unilateral and located in the lower and lateral parts of the chest. Deep breathing, coughing, or thoracic movement aggravates the pain. Decreased breath sounds and inspiratory crackles may be heard over the painful area. Other findings include dyspnea, tachypnea, tachycardia, cyanosis, a fever, and fatigue.

Pneumonia (bacterial). A pleural friction rub occurs with bacterial pneumonia, which usually starts with a dry, painful, hacking cough that rapidly becomes productive. Related effects develop suddenly; these include shaking chills, a high fever, a headache, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia, grunting respirations, nasal flaring, dullness to percussion, and cyanosis. Auscultation reveals decreased breath sounds and fine crackles.

Pulmonary embolism. An embolism can cause a pleural friction rub over the affected area of the lung. Usually, the first symptom is sudden dyspnea, which may be accompanied by angina or unilateral pleuritic chest pain. Other clinical features include a nonproductive cough or a cough that produces blood-tinged sputum, tachycardia, tachypnea, a low-grade fever, restlessness, and diaphoresis. Less common findings include massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema and, with a large embolus, cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention. Crackles, diffuse wheezing, decreased breath sounds, and signs of circulatory collapse may also occur.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Pulmonary involvement can cause a pleural friction rub, hemoptysis, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and crackles. More characteristic effects of SLE include a butterfly rash, nondeforming joint pain and stiffness, and photosensitivity. A fever, anorexia, weight loss, and lymphadenopathy may also occur.

Tuberculosis (pulmonary). With pulmonary TB, a pleural friction rub may occur over the affected part of the lung. Early signs and symptoms include weight loss, night sweats, a lowgrade fever in the afternoon, malaise, dyspnea, anorexia, and easy fatigability. Progression of the disorder usually produces pleuritic pain, fine crackles over the upper lobes, and a productive

cough with blood-streaked sputum. Advanced TB can cause chest retraction, tracheal deviation, and dullness to percussion.

Other Causes

Treatments. Thoracic surgery and radiation therapy can cause a pleural friction rub.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s respiratory status and vital signs. If the patient’s persistent dry, hacking cough tires him, administer an antitussive. (Avoid giving an opioid, which can further depress respirations.) Administer oxygen and an antibiotic. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests such as chest X-rays.

Patient Counseling

Discuss pain relief measures, and explain which signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

Auscultate for a pleural friction rub in a child who has grunting respirations, reports chest pain, or protects his chest by holding it or lying on one side. A pleural friction rub in a child is usually an early sign of pleurisy.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, the intensity of pleuritic chest pain may mimic that of cardiac chest pain.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Polydipsia

Polydipsia refers to excessive thirst, a common symptom associated with endocrine disorders and certain drugs. It may reflect decreased fluid intake, increased urine output, or excessive loss of water and salt.

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a history. Find out how much fluid the patient drinks each day. How often and how much does he typically urinate? Does the need to urinate awaken him at night? Determine if he or anyone in his family has diabetes or kidney disease. What medications does he use? Has his lifestyle changed recently? If so, have these changes upset him?

If the patient has polydipsia, take his blood pressure and pulse when he’s in supine and standing positions. A decrease of 10 mm Hg in systolic pressure and a pulse rate increase of 10 beats/minute from the supine to the sitting or standing position may indicate hypovolemia. If you detect these changes, ask the patient about recent weight loss. Check for signs of dehydration, such as dry mucous membranes and decreased skin turgor. Infuse I.V. replacement fluids, as needed.

Medical Causes

Diabetes insipidus. Diabetes insipidus characteristically produces polydipsia and may also cause excessive voiding of dilute urine and mild to moderate nocturia. Fatigue and signs of dehydration occur in severe cases.

Diabetes mellitus. Polydipsia is a classic finding with diabetes mellitus — a consequence of the hyperosmolar state. Other characteristic findings include polyuria, polyphagia, nocturia, weakness, fatigue, and weight loss. Signs of dehydration may occur.

Hypercalcemia. As hypercalcemia progresses, the patient develops polydipsia, polyuria, nocturia, constipation, paresthesia and, occasionally, hematuria and pyuria. Severe hypercalcemia can progress quickly to vomiting, a decreased level of consciousness, and renal failure. Depression, mental lassitude, and increased sleep requirements are common.

Hypokalemia. Hypokalemia is an electrolyte imbalance that can cause nephropathy, resulting in polydipsia, polyuria, and nocturia. Related hypokalemic signs and symptoms include muscle weakness or paralysis, fatigue, decreased bowel sounds, hypoactive deep tendon reflexes, and arrhythmias.

Psychogenic polydipsia. Psychogenic polydipsia is an uncommon disorder that causes polydipsia and polyuria. It may occur with any psychiatric disorder, but is more common with schizophrenia. Signs of psychiatric disturbances, such as anxiety or depression, are typical. Other findings include a headache, blurred vision, weight gain, edema, elevated blood pressure and, occasionally, stupor and coma. Signs of heart failure may develop with overhydration.

Renal disorders (chronic). Chronic renal disorders, such as glomerulonephritis and pyelonephritis, damage the kidneys, causing polydipsia and polyuria. Associated signs and symptoms include nocturia, weakness, elevated blood pressure, pallor and, in later stages, oliguria.

Sheehan’s syndrome. Polydipsia, polyuria, and nocturia occur with Sheehan’s syndrome, a disorder of postpartum pituitary necrosis. Other features include fatigue, failure to lactate, amenorrhea, decreased pubic and axillary hair growth, and a reduced libido.

Sickle cell anemia. As nephropathy develops, polydipsia and polyuria occur. They may be accompanied by abdominal pain and cramps, arthralgia and, occasionally, lower extremity skin ulcers and bone deformities, such as kyphosis and scoliosis.

Other Causes

Drugs. Diuretics and demeclocycline may produce polydipsia. Phenothiazines and anticholinergics can cause dry mouth, making the patient so thirsty that he drinks compulsively.

Special Considerations

Carefully monitor the patient’s fluid balance by recording his total intake and output. Weigh the patient at the same time each day, in the same clothing, and using the same scale. Regularly check blood pressure and pulse in the supine and standing positions to detect orthostatic hypotension, which may indicate hypovolemia. Because thirst is usually the body’s way of compensating for water loss, give the patient ample liquids.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying disorder and treatment. Teach the patient about diet, exercise, and home blood glucose monitoring. Stress the importance of reporting weight gain or loss.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, polydipsia usually stems from diabetes insipidus or diabetes mellitus. Rare causes include pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma, and Prader-Willi syndrome. However, some children develop habitual polydipsia that’s unrelated to any disease.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Polyphagia

[Hyperphagia]

Polyphagia refers to voracious or excessive eating. This common symptom can be persistent or intermittent, resulting primarily from endocrine and psychological disorders as well as the use of certain drugs. Depending on the underlying cause, polyphagia may cause weight gain.

History and Physical Examination

Begin your evaluation by asking the patient what he has eaten and drunk within the past 24 hours. (If he easily recalls this information, ask about his intake for the 2 previous days, for a broader view of his dietary habits.) Note the frequency of meals and the amount and types of food eaten. Find out if the patient’s eating habits have changed recently. Has he always had a large appetite? Does his overeating alternate with periods of anorexia? Ask about conditions that may trigger overeating, such as stress, depression, or menstruation. Does the patient actually feel hungry, or does he eat simply because food is available? Does he ever vomit or have a headache after overeating?

Explore related signs and symptoms. Has the patient recently gained or lost weight? Does he feel tired, nervous, or excitable? Has he experienced heat intolerance, dizziness, palpitations, diarrhea, or increased thirst or urination? Obtain a complete drug history, including the use of laxatives or

enemas.

During the physical examination, weigh the patient. Tell him his current weight, and watch for an expression of disbelief or anger. Inspect the skin to detect dryness or poor turgor. Palpate the thyroid for enlargement.

Medical Causes

Anxiety. Polyphagia may result from mild to moderate anxiety or emotional stress. Mild anxiety typically produces restlessness, sleeplessness, irritability, repetitive questioning, and constant seeking of attention and reassurance. With moderate anxiety, selective inattention and difficulty concentrating may also occur. Other effects of anxiety may include muscle tension, diaphoresis, GI distress, palpitations, tachycardia, and urinary and sexual dysfunction.

Bulimia. Most common in women ages 18 to 29, bulimia causes polyphagia that alternates with self-induced vomiting, fasting, or diarrhea. The patient typically weighs less than normal, but has a morbid fear of obesity. She appears depressed, has low self-esteem, and conceals her overeating.

Diabetes mellitus. With diabetes mellitus, polyphagia occurs with weight loss, polydipsia, and polyuria. It’s accompanied by nocturia, weakness, fatigue, and signs of dehydration, such as dry mucous membranes and poor skin turgor.

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Appetite changes, typified by food cravings and binges, are common with PMS. Abdominal bloating, the most common associated finding, may occur with behavioral changes, such as depression and insomnia. A headache, paresthesia, and other neurologic symptoms may also occur. Related findings include diarrhea or constipation, edema and temporary weight gain, palpitations, back pain, breast swelling and tenderness, oliguria, and easy bruising.

Other Causes

Drugs. Corticosteroids, cyproheptadine, and some hormone supplements may increase appetite, causing weight gain.

Special Considerations

Offer the patient with polyphagia emotional support, and help him understand its underlying cause. As needed, refer him and his family for psychological counseling.

Patient Counseling

Refer the patient for nutritional counseling as well as for personal and family counseling. Provide emotional support, and help the patient to understand the disease process.

Pediatric Pointers

In a child, polyphagia commonly results from juvenile diabetes. In an infant ages 6 to 18 months, it can result from a malabsorptive disorder such as celiac disease. However, polyphagia may occur normally in a child who’s experiencing a sudden growth spurt.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

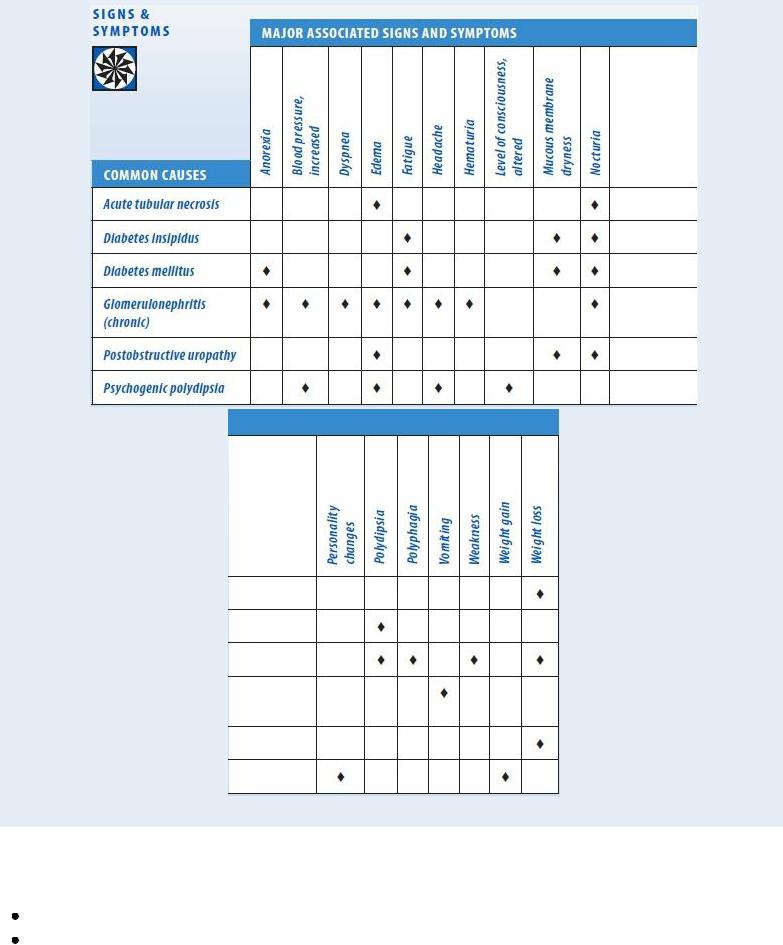

Polyuria

A relatively common sign, polyuria is the daily production and excretion of more than 3 L of urine. It’s usually reported by the patient as increased urination, especially when it occurs at night. Polyuria is aggravated by overhydration, consumption of caffeine or alcohol, and excessive ingestion of salt, glucose, or other hyperosmolar substances. (See Polyuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 578 and 579.)

Polyuria usually results from the use of certain drugs, such as a diuretic, or from a psychological, neurologic, or renal disorder. It can reflect central nervous system dysfunction that diminishes or suppresses antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion, which regulates fluid balance. Or, when ADH levels are normal, it can reflect renal impairment. In both of these pathophysiologic mechanisms, the renal tubules fail to reabsorb sufficient water, causing polyuria.

History and Physical Examination

Because the patient with polyuria is at risk for developing hypovolemia, evaluate his fluid status first. Take his vital signs, noting an increased body temperature, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension (a ≥10 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure upon standing and a ≥10 beats/minute increase in heart rate upon standing). Inspect for dry skin and mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor and elasticity, and reduced perspiration. Is the patient unusually tired or thirsty? Has he recently lost more than 5% of his body weight? If you detect these effects of hypovolemia, you’ll need to infuse replacement fluids.

If the patient doesn’t display signs of hypovolemia, explore the frequency and pattern of the polyuria. When did it begin? How long has it lasted? Was it precipitated by a certain event? Ask the patient to describe the pattern and amount of his daily fluid intake. Check for a history of visual deficits, headaches, or head trauma, which may precede diabetes insipidus. Also, check for a history of urinary tract obstruction, diabetes mellitus, renal disorders, chronic hypokalemia or hypercalcemia, or psychiatric disorders (past and present). Find out the schedule and dosage of any drugs the patient is taking.

Perform a neurologic examination, noting especially any change in the patient’s level of consciousness. Then, palpate the bladder, and inspect the urethral meatus. Obtain a urine specimen, and check its specific gravity.

Medical Causes

Acute tubular necrosis. During the diuretic phase of acute tubular necrosis, polyuria of less

than 8 L/day gradually subsides after 8 to 10 days. Urine specific gravity (1.010 or less) increases as polyuria subsides. Related findings include weight loss, decreasing edema, and nocturia.

Diabetes insipidus. Polyuria of about 5 L/day with a specific gravity of 1.005 or less is common, although extreme polyuria — up to 30 L/day — occasionally occurs. Polyuria is commonly accompanied by polydipsia, nocturia, fatigue, and signs of dehydration, such as poor skin turgor and dry mucous membranes.

Diabetes mellitus. With diabetes mellitus, polyuria seldom exceeds 5 L/day, and urine specific gravity typically exceeds 1.020. The patient usually reports polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss, weakness, frequent urinary tract infections and yeast vaginitis, fatigue, and nocturia. The patient may also display signs of dehydration and anorexia.

Glomerulonephritis (chronic). Polyuria gradually progresses to oliguria with chronic glomerulonephritis. Urine output is usually less than 4 L/day; specific gravity is about 1.010. Related GI findings include anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. The patient may experience drowsiness, fatigue, edema, a headache, elevated blood pressure, and dyspnea. Nocturia, hematuria, frothy or malodorous urine, and mild to severe proteinuria may occur.

Postobstructive uropathy. After resolution of a urinary tract obstruction, polyuria — usually more than 5 L/day with a specific gravity of less than 1.010 — occurs for up to several days before gradually subsiding. Bladder distention and edema may occur with nocturia and weight loss. Occasionally, signs of dehydration appear.

Psychogenic polydipsia. Most common in people older than age 30, psychogenic polydipsia usually produces dilute polyuria of 3 to 15 L/day, depending on fluid intake. The patient may appear depressed and have a headache and blurred vision. Weight gain, edema, elevated blood pressure and, occasionally, stupor or coma may develop. With severe overhydration, signs of heart failure may be present.

Polyuria: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Transient polyuria can result from radiographic tests that use contrast media. Drugs. Diuretics characteristically produce polyuria. Cardiotonics, vitamin D, demeclocycline, phenytoin, lithium, and propoxyphene can also produce polyuria.

Special Considerations

Maintaining adequate fluid balance is your primary concern when the patient has polyuria. Record his intake and output accurately, and weigh him daily. Closely monitor the patient’s vital signs to detect fluid imbalance, and encourage him to drink adequate fluids. Review his medications, and recommend modification where possible to help control symptoms.

Prepare the patient for serum electrolyte, osmolality, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine studies to monitor fluid and electrolyte status and for a fluid deprivation test to determine the cause of polyuria.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient about the underlying disorder and which signs and symptoms of dehydration he should report. Explain the importance of fluid replacement, and instruct the patient on weight monitoring.

Pediatric Pointers

The major causes of polyuria in children are congenital nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, medullary cystic disease, polycystic renal disease, and distal renal tubular acidosis.

Because a child’s fluid balance is more delicate than an adult’s, check his urine specific gravity at each voiding, and be alert for signs of dehydration. These include a decrease in body weight; decreased skin turgor; pale, mottled, or gray skin; dry mucous membranes; decreased urine output; and an absence of tears when crying.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, chronic polyuria is commonly associated with an underlying disorder. The possibility of associated malignant disease must be investigated.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Priapism

A urologic emergency, priapism is a persistent, painful erection that’s unrelated to sexual excitation. This relatively rare sign may begin during sleep and appear to be a normal erection, but it may last for several hours or days. It’s usually accompanied by a severe, constant, dull aching in the penis. Despite the pain, the patient may be too embarrassed to seek medical help and may try to achieve detumescence through continued sexual activity.

Priapism occurs when the veins of the corpora cavernosa fail to drain correctly, resulting in persistent engorgement of the tissues. Without prompt treatment, penile ischemia and thrombosis

occur. In about half of all cases, priapism is idiopathic and develops without apparent predisposing factors. Secondary priapism can result from a blood disorder, neoplasm, trauma, or the use of certain drugs.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has priapism, apply an ice pack to the penis, administer an analgesic, and insert an indwelling urinary catheter to relieve urine retention. Procedures to remove blood from the corpora cavernosa, such as irrigation and surgery, may be required.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him when the priapism began. Is it continuous or intermittent? Has he had a prolonged erection before? If so, what did he do to relieve it? How long did he remain detumescent? Does he have pain or tenderness when he urinates? Has he noticed changes in sexual function?

Explore the patient’s medical history. If he reports sickle cell anemia, find out about factors that could precipitate a crisis, such as dehydration and infection. Ask if he has recently suffered genital trauma, and obtain a thorough drug history. Ask if he has had drugs injected or objects inserted into his penis.

Examine the patient’s penis, noting its color and temperature. Check for loss of sensation and signs of infection, such as redness or drainage. Finally, take his vital signs, particularly noting a fever.

Medical Causes

Penile cancer. Cancer that exerts pressure on the corpora cavernosa can cause priapism. Usually, the first sign is a painless ulcerative lesion or an enlarging warty growth on the glans or foreskin, which may be accompanied by localized pain, a foul-smelling discharge from the prepuce, a firm lump near the glans, and lymphadenopathy. Later findings include bleeding, dysuria, urine retention, and bladder distention. Phimosis and poor hygiene have been linked to the development of penile cancer.

Sickle cell anemia. With sickle cell anemia, painful priapism can occur without warning, usually on awakening. The patient may have a history of priapism, impaired growth and development, and an increased susceptibility to infection. Related findings include tachycardia, pallor, weakness, hepatomegaly, dyspnea, joint swelling, joint or bone aching, chest pain, fatigue, murmurs, leg ulcers and, possibly, jaundice and gross hematuria.

With sickle cell crisis, signs and symptoms of sickle cell anemia may worsen and others, such as abdominal pain and a low-grade fever, may appear.

Spinal cord injury. With spinal cord injury, the patient may be unaware of the onset of priapism. Related effects depend on the extent and level of injury and may include autonomic signs such as bradycardia.

Stroke. A stroke may cause priapism, but sensory loss and aphasia may prevent the patient from noticing or describing it. Other findings depend on the stroke’s location and extent, but may