Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

In a well-lit examining room, observe the patient’s breasts. Estimate the extent of the peau d’orange, and check for erythema. Assess the nipples for discharge, deviation, retraction, dimpling, and cracking. Gently palpate the area of peau d’orange, noting warmth or induration. Then, palpate the entire breast, noting fixed or mobile lumps, and the axillary lymph nodes, noting enlargement. Finally, take the patient’s temperature.

Medical Causes

Breast abscess. Usually affecting lactating women with milk stasis, breast abscess causes peau d’orange, malaise, breast tenderness and erythema, and a sudden fever that may be accompanied by shaking chills. A cracked nipple may produce a purulent discharge, and an indurated or palpable soft mass may be present.

Breast cancer. Advanced breast cancer is the most likely cause of peau d’orange, which usually begins in the dependent part of the breast or the areola. Palpation typically reveals a firm, immobile mass that adheres to the skin above the area of peau d’orange. Inspection of the breasts may reveal changes in contour, size, or symmetry. Inspection of the nipples may reveal deviation, erosion, retraction, and a thin and watery, bloody, or purulent discharge. The patient may report a burning and itching sensation in the nipples as well as a sensation of warmth or heat in the breast. Breast pain may occur, but it isn’t a reliable indicator of cancer.

Special Considerations

Because peau d’orange usually signals advanced breast cancer, provide emotional support for the patient. Encourage her to express her fears and concerns. Clearly explain expected diagnostic tests, such as mammography and breast biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Explain diagnostic tests the patient needs, and teach her how to do monthly breast self-examinations. Discuss signs and symptoms she needs to report.

REFERENCES

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Pericardial Friction Rub

Commonly transient, a pericardial friction rub is a scratching, grating, or crunching sound that occurs when two inflamed layers of the pericardium slide over one another. Ranging from faint to loud, this abnormal sound is best heard along the lower left sternal border during deep inspiration. It indicates pericarditis, which can result from an acute infection, a cardiac or renal disorder, postpericardiotomy syndrome, or the use of certain drugs.

Occasionally, a pericardial friction rub can resemble a murmur (See Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?) or a pleural friction rub. However, the classic pericardial friction rub has three components. (See Understanding Pericardial Friction Rubs.)

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a complete medical history, noting especially cardiac dysfunction. Has the patient recently had a myocardial infarction or cardiac surgery? Has he ever had pericarditis or a rheumatic disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus? Does he have chronic renal failure or an infection? If the patient complains of chest pain, ask him to describe its character and location. What relieves the pain? What worsens it?

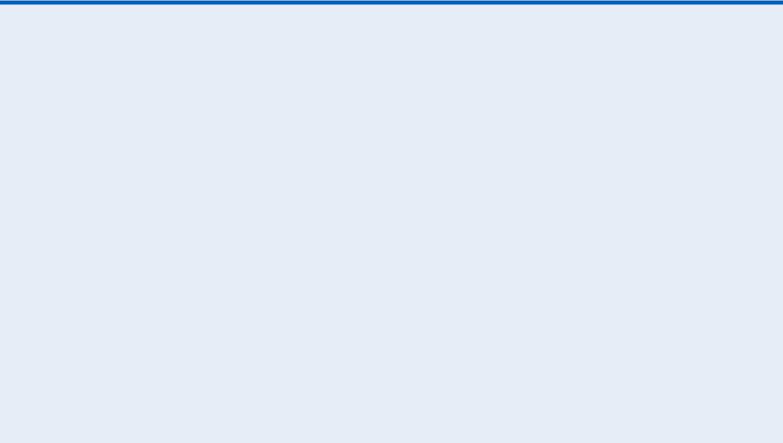

Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially hypotension, tachycardia, an irregular pulse, tachypnea, and a fever. Inspect for jugular vein distention, edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly. Auscultate the lungs for crackles. (See Comparing Auscultation Findings, pages 564 and 565.)

EXAMINATION TIP Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?

EXAMINATION TIP Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?

Is the sound you hear a pericardial friction rub or a murmur? Here’s how to tell. The classic pericardial friction rub has three sound components, which are related to the phases of the cardiac cycle. In some patients, however, the rub’s presystolic and early diastolic sounds may be inaudible, causing the rub to resemble the murmur of mitral insufficiency or aortic stenosis and insufficiency.

If you don’t detect the classic three-component sound, you can distinguish a pericardial friction rub from a murmur by auscultating again and asking yourself these questions:

HOW DEEP IS THE SOUND?

A pericardial friction rub usually sounds superficial; a murmur sounds deeper in the chest.

DOES THE SOUND RADIATE?

A pericardial friction rub usually doesn’t radiate; a murmur may radiate widely.

DOES THE SOUND VARY WITH INSPIRATION OR CHANGES IN

PATIENT POSITION?

A pericardial friction rub is usually loudest during inspiration and is best heard when the patient leans forward. A murmur varies in timing and duration with both factors.

Medical Causes

Pericarditis. A pericardial friction rub is the hallmark of acute pericarditis. This disorder also causes sharp precordial or retrosternal pain that usually radiates to the left shoulder, neck, and back. The pain worsens when the patient breathes deeply, coughs, or lies flat and, possibly, when he swallows. It abates when he sits up and leans forward. The patient may also develop a fever, dyspnea, tachycardia, and arrhythmias.

Comparing Auscultation Findings

During auscultation, you may detect a pleural friction rub, a pericardial friction rub, or crackles

— three abnormal sounds that are commonly confused. Use these illustrations to help clarify auscultation findings.

EXAMINATION TIP Understanding Pericardial Friction

EXAMINATION TIP Understanding Pericardial Friction

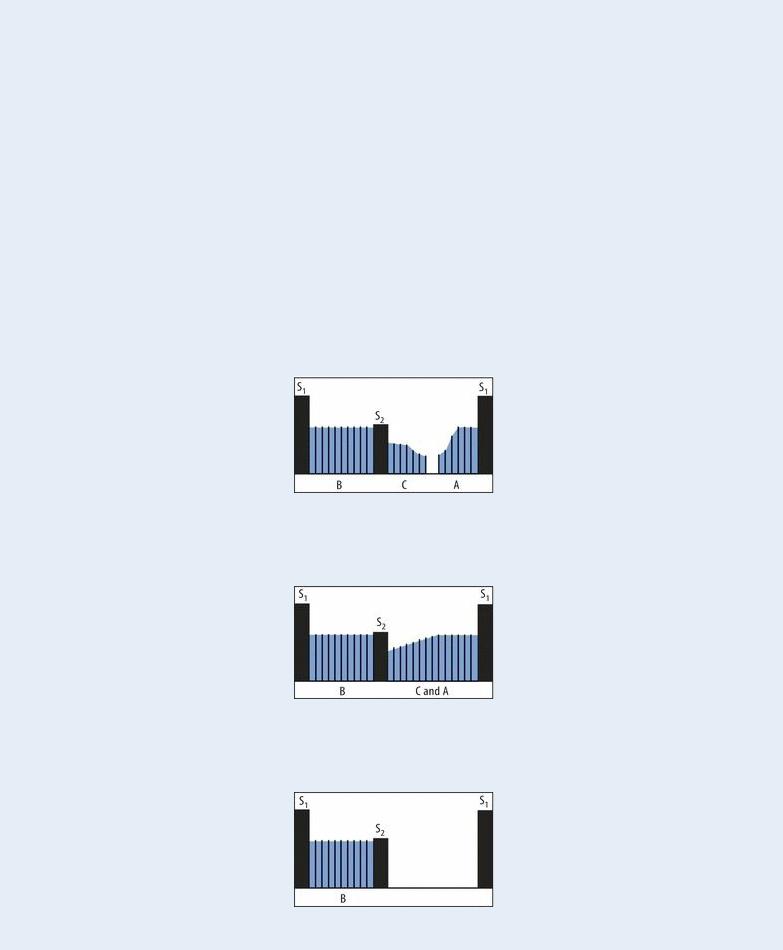

Rubs

The complete, or classic, pericardial friction rub is triphasic. Its three sound components are linked to phases of the cardiac cycle. The presystolic component (A) reflects atrial systole and precedes the first heart sound (S1). The systolic component (B) — usually the loudest — reflects ventricular systole and occurs between the S1 and second heart sound (S2). The early diastolic component (C) reflects ventricular diastole and follows S2.

Sometimes, the early diastolic component merges with the presystolic component, producing a diphasic to-and-fro sound on auscultation. In other patients, auscultation may detect only one component — a monophasic rub, typically during ventricular systole.

TRIPHASIC RUB

DIPHASIC RUB

MONOPHASIC RUB

With chronic constrictive pericarditis, a pericardial friction rub develops gradually and is accompanied by signs of decreased cardiac filling and output, such as peripheral edema, ascites, jugular vein distention on inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign), and hepatomegaly. Dyspnea, orthopnea,

paradoxical pulse, and chest pain may also occur.

Other Causes

Drugs. Procainamide and chemotherapeutic drugs can cause pericarditis.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s cardiovascular status. If the pericardial friction rub disappears, be alert for signs of cardiac tamponade: pallor; cool, clammy skin; hypotension; tachycardia; tachypnea; paradoxical pulse; and increased jugular vein distention. If these signs occur, prepare the patient for pericardiocentesis to prevent cardiovascular collapse.

Ensure that the patient gets adequate rest. Give an anti-inflammatory, antiarrhythmic, diuretic, or antimicrobial to treat the underlying cause. If necessary, prepare him for a pericardiectomy to promote adequate cardiac filling and contraction.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying disorder, its treatments, and what the patient can do to minimize his symptoms.

Pediatric Pointers

Bacterial pericarditis may develop during the first two decades of life, usually before age 6. Although a pericardial friction rub may occur, other signs and symptoms — such as a fever, tachycardia, dyspnea, chest pain, jugular vein distention, and hepatomegaly — more reliably indicate this lifethreatening disorder. A pericardial friction rub may also occur after surgery to correct congenital cardiac anomalies. However, it usually vanishes without the development of pericarditis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Peristaltic Waves, Visible

With intestinal obstruction, peristalsis temporarily increases in strength and frequency as the intestine contracts to force its contents past the obstruction. As a result, visible peristaltic waves may roll across the abdomen. Typically, these waves appear suddenly and vanish quickly because increased peristalsis overcomes the obstruction or the GI tract becomes atonic. Peristaltic waves are best detected by stooping at the patient’s side and inspecting his abdominal contour while he’s in a supine position.

Visible peristaltic waves may also reflect normal stomach and intestinal contractions in thin patients or in malnourished patients with abdominal muscle atrophy.

History and Physical Examination

After observing peristaltic waves, collect pertinent history data. Ask about a history of a pyloric ulcer, stomach cancer, or chronic gastritis, which can lead to pyloric obstruction. Also, ask about conditions leading to intestinal obstruction, such as intestinal tumors or polyps, gallstones, chronic constipation, and a hernia. Has the patient had recent abdominal surgery? Make sure to obtain a drug history.

Determine if the patient has related symptoms. Spasmodic abdominal pain, for example, accompanies small-bowel obstruction, whereas colicky pain accompanies pyloric obstruction. Is the patient experiencing nausea and vomiting? If he has vomited, ask about the consistency, amount, and color of the vomitus. Lumpy vomitus may contain undigested food particles; green or brown vomitus may contain bile or fecal matter.

Next, with the patient in a supine position, inspect the abdomen for distention, surgical scars and adhesions, or visible loops of bowel. Auscultate for bowel sounds, noting high-pitched, tinkling sounds. Then, jar the patient’s bed (or roll the patient from side to side) and auscultate for a succussion splash — a splashing sound in the stomach from retained secretions due to pyloric obstruction. Palpate the abdomen for rigidity and tenderness, and percuss for tympany. Check the skin and mucous membranes for dryness and poor skin turgor, indicating dehydration. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially tachycardia and hypotension, which indicate hypovolemia.

Medical Causes

Large-bowel obstruction. Visible peristaltic waves in the upper abdomen are an early sign of large-bowel obstruction. Obstipation, however, may be the earliest finding. Other characteristic signs and symptoms develop more slowly than in small-bowel obstruction. These include nausea, colicky abdominal pain (milder than in small-bowel obstruction), gradual and eventually marked abdominal distention, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

Pyloric obstruction. Peristaltic waves may be detected in a swollen epigastrium or in the left upper quadrant, usually beginning near the left rib margin and rolling from left to right. Related findings include vague epigastric discomfort or colicky pain after eating, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Auscultation reveals a loud succussion splash.

Small-bowel obstruction. Early signs of mechanical obstruction of the small bowel include peristaltic waves rolling across the upper abdomen and intermittent, cramping periumbilical pain. Associated signs and symptoms include nausea, vomiting of bilious or, later, fecal material, and constipation; in partial obstruction, diarrhea may occur. Hyperactive bowel sounds and slight abdominal distention also occur early.

Special Considerations

Because visible peristaltic waves are an early sign of intestinal obstruction, monitor the patient’s status and prepare him for diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Withhold food and fluids, and explain the purpose and procedure of abdominal X-rays and barium studies, which can confirm obstruction.

If tests confirm obstruction, nasogastric suctioning may be performed to decompress the stomach and small bowel. Provide frequent oral hygiene, and watch for a thick, swollen tongue and dry mucous membranes, indicating dehydration. Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs and intake and output.

Patient Counseling

Discuss dietary and fluid requirements. Encourage the use of stool softeners and increased intake of high-fiber foods for patients with chronic constipation.

Pediatric Pointers

In infants, visible peristaltic waves may indicate pyloric stenosis. In small children, peristaltic waves may be visible normally because of the protuberant abdomen, or visible waves may indicate bowel obstruction stemming from congenital anomalies, volvulus, or swallowing a foreign body.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients who present with visible peristaltic waves, always check for fecal impaction, which is a common problem among those of this age group. Also, obtain a detailed drug history; antidepressants and antipsychotics can predispose patients to constipation and bowel obstruction.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Photophobia

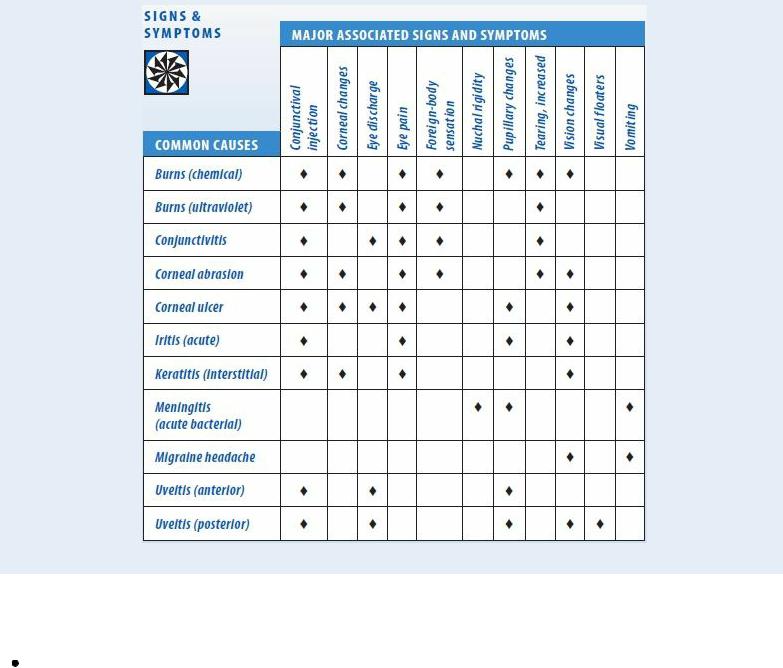

A common symptom, photophobia is an abnormal sensitivity to light. In many patients, photophobia simply indicates increased eye sensitivity without underlying pathology. For example, it can stem from wearing contact lenses excessively or using poorly fitted lenses. However, in others, this symptom can result from a systemic disorder, an ocular disorder or trauma, or the use of certain drugs. (See Photophobia: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports photophobia, find out when it began and how severe it is. Did it follow eye trauma, a chemical splash, or exposure to the rays of a sun lamp? If photophobia results from trauma, avoid manipulating the eyes. Ask the patient about eye pain and have him describe its location, duration, and intensity. Does he have a sensation of a foreign body in his eye? Does he have other signs and symptoms, such as increased tearing and vision changes?

Next, take the patient’s vital signs, and assess his neurologic status. Assess visual activity, unless the cause is a chemical burn. Follow this with a careful eye examination, inspecting the eyes’ external structures for abnormalities. Examine the conjunctiva and sclera, noting their color. Characterize the amount and consistency of any discharge. Then, check pupillary reaction to light. Evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze, and test visual acuity in both eyes.

During your assessment, keep in mind that although photophobia can accompany life-threatening meningitis, it isn’t a cardinal sign of meningeal irritation.

Medical Causes

Burns. With a chemical burn, photophobia and eye pain may be accompanied by erythema and blistering on the face and lids, miosis, diffuse conjunctival injection, and corneal changes. The patient experiences blurred vision and may be unable to keep his eyes open. With an ultraviolet radiation burn, photophobia occurs with moderate to severe eye pain. These symptoms develop about 12 hours after exposure to the rays of a welding arc or sun lamp.

Conjunctivitis. Moderate to severe conjunctivitis can cause photophobia. Other common findings of conjunctivitis include conjunctival injection, increased tearing, a foreign body sensation, a feeling of fullness around the eyes, and eye pain, burning, and itching. Allergic conjunctivitis is distinguished by a stringy white eye discharge and milky red injection. Bacterial conjunctivitis tends to cause a copious, mucopurulent, flaky eye discharge that may make the eyelids stick together as well as brilliant red conjunctiva. Fungal conjunctivitis produces a thick, purulent discharge, extreme redness, and crusting, sticky eyelids. Viral conjunctivitis causes copious tearing with little discharge as well as enlargement of the preauricular lymph nodes.

Corneal abrasion. A common finding with corneal abrasion, photophobia is usually accompanied by excessive tearing, conjunctival injection, visible corneal damage, and a foreign body sensation in the eye. Blurred vision and eye pain may also occur.

Corneal ulcer. A corneal ulcer is a vision-threatening disorder that causes severe photophobia and eye pain aggravated by blinking. Impaired visual acuity may accompany blurring, eye discharge, and sticky eyelids. Conjunctival injection may occur even though an area of the cornea may appear white and opaque. A bacterial ulcer may be irregularly shaped. A fungal ulcer may be surrounded by progressively clearer rings.

Iritis (acute). Severe photophobia may result from acute iritis, along with marked conjunctival injection, moderate to severe eye pain, and blurred vision. The pupil may be constricted and may respond poorly to light.

Keratitis (interstitial). Keratitis is a corneal inflammation that causes photophobia, eye pain, blurred vision, dramatic conjunctival injection, and cloudy corneas.

Meningitis (acute bacterial). A common symptom of meningitis, photophobia may occur with other signs of meningeal irritation, such as nuchal rigidity, hyperreflexia, and opisthotonos. Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs can be elicited. A fever, an early finding, may be accompanied by chills. Related signs and symptoms may include a headache, vomiting, ocular palsies, facial weakness, pupillary abnormalities, and hearing loss. With severe meningitis, seizures may occur along with stupor progressing to coma.

Migraine headache. Photophobia and noise sensitivity are prominent features of a common migraine. Typically severe, this aching or throbbing headache may also cause fatigue, blurred vision, nausea, and vomiting.

Uveitis. Anterior and posterior uveitis can cause photophobia. Typically, anterior uveitis also produces moderate to severe eye pain, severe conjunctival injection, and a small, nonreactive pupil. Posterior uveitis develops slowly, causing visual floaters, eye pain, pupil distortion, conjunctival injection, and blurred vision.

Photophobia: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Other Causes

Drugs. Mydriatics — such as phenylephrine, atropine, scopolamine, cyclopentolate, and tropicamide — can cause photophobia due to pupillary dilation. Amphetamines, cocaine, and ophthalmic antifungals — such as trifluridine and idoxuridine — can also cause photophobia.

Special Considerations

Promote the patient’s comfort by darkening the room and telling him to close the eyes. If photophobia persists at home, suggest that he wear dark glasses. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as corneal scraping and slit-lamp examination.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disorder and treatment plan, and discuss ways to relieve discomfort. Teach the patient how to instill eye drops and ointments as ordered.

Pediatric Pointers

Suspect photophobia in any child who squints, rubs his eyes frequently, or wears sunglasses indoors

and outside. Congenital disorders, such as albinism, and childhood diseases, such as measles and rubella, can cause photophobia.

REFERENCES

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Holland, E. J., Mannis, M. J., & Lee, W. B. (2013) . Ocular surface disease: Cornea, conjunctiva, and tear film. London, UK: Elsevier Saunders.

Huang, J. J., & Gaudio, P. A. (2010). Ocular inflammatory disease and uveitis manual: Diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia, PA : Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Levin, L. A., & Albert, D. M. (2010). Ocular disease: Mechanisms and management. London, UK: Saunders, Elsevier. Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee—Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

Pleural Friction Rub

Commonly resulting from a pulmonary disorder or trauma, this loud, coarse, grating, creaking, or squeaking sound may be auscultated over one or both lungs during late inspiration or early expiration. It’s heard best over the low axilla or the anterior, lateral, or posterior bases of the lung fields with the patient upright. Sometimes intermittent, it may resemble crackles or a pericardial friction rub. (See

Comparing Auscultation Findings, pages 564 and 565.)

A pleural friction rub indicates inflammation of the visceral and parietal pleural lining, which causes congestion and edema. The resultant fibrinous exudate covers both pleural surfaces, displacing the fluid that’s normally between them and causing the surfaces to rub together.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

When you detect a pleural friction rub, quickly look for signs of respiratory distress: shallow or decreased respirations; crowing, wheezing, or stridor; dyspnea; increased accessory muscle use; intercostal or suprasternal retractions; cyanosis; and nasal flaring. Check for hypotension, tachycardia, and a decreased level of consciousness.

If you detect signs of distress, open and maintain an airway. Endotracheal intubation and supplemental oxygen may be necessary. Insert a large-bore I.V. line to deliver drugs and fluids. Elevate the patient’s head 30 degrees. Monitor his cardiac status constantly, and check his vital signs frequently.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe distress, explore related symptoms. Find out if he has had chest pain. If so, ask him to describe its location and severity. How long does his chest pain last? Does the pain radiate to his shoulder, neck, or upper abdomen? Does the pain worsen with breathing, movement, coughing, or sneezing? Does the pain abate if he splints his chest, holds his breath, or exerts pressure or lies on the affected side?

CULTURAL CUE

CULTURAL CUE