- •2.2. Содержание курса по теоретической фонетике. Введение.

- •I. Методы исследования звукового строя английского языка.

- •П. Английское литературное произношение.

- •III. Устная и письменная формы речи.

- •IV. Фонетическая база английского языка.

- •V. Теория фонемы.

- •VI. Фонемный состав английского языка.

- •VII. Позиционно-комбинаторные изменения фонем английского языка.

- •VIII. Фонологические и нефонологические чередования в английском языке.

- •IX. Слогообразование и слогоделение в английском языке.

- •X. Словесное ударение в английском языке.

- •XI. Интонация английского языка.

- •XII. Фоностилистика современного английского языка.

- •2.3.2. Тематический план лекционного курса.

- •2.3.3. Тематический план практических (семинарских) занятий.

- •Перечень теоретических вопросов к экзамену.

- •Лекции The subject-matter of phonetics. Its’s connection with linguistic and non-linguistic sciences. Significance and subdivision of phonetics.

- •Aspects of phonetics.

- •Components of the phonetic system of lanquage.

- •Methods of phonetic analysis

- •Articulatory and physiological aspect of speech sounds.

- •Articulatory and physiological cassification of English consonants.

- •Modification of consonants in connected speech.

- •Articulatory and physiological classification of English vowels.

- •Modification of vowels in connected speech

- •Differences in the articulation bases of English and Russian consonants and vowels.

- •The functional aspect of speech sounds. The phoneme.

- •Syllabic structure of English words.

- •Accentual structure of English words.

- •Intonation.

- •2. Components of intonation and the structure of English intonation group.

- •3. Graphical representation of intonation

- •4. Rhythm.

- •5. Emphasis

- •Territorial, social and stylistic varieties of English pronunciation.

5. Emphasis

To make the utterances more lively, emotional or exclamatory – emphatic – pitch is used. Or different sections of pitch-and-stress patterns.

For example, if the Low Falling nuclear tone is changed for the High Fall, the intonation group sounds more emphatic – more chategoric, firm, finel, concerned:

Do you want to stay here? - \No, | I \don’t.

Do you want to stay here? – ٰNo, | I ٰdon’t.

Another way of adding emphasis is by modifying the shape of the head. For instance, the Falling Head can be modified for emphasis by pronouncing the unstressed syllables on the same level as the stressed ones:

\, Ask him to ′ring me ٰup \again.

Often the emphasis is achieved by modifying one section of the pitch-and-stress pattern, but also by combining the modifications in pre-heads, heads and nuclear tones. The pitch-and-stress sections of intonation can be roughly divided into non-emphatic and emphatic:

|

Pitch-and-stress sections |

Non-emphatic |

Emphatic |

|

|

Pre-heads |

Low Pre-Head |

High Pre-Head |

|

|

Heads |

Descending |

Falling Head |

Stepping, Sliding, Scandent, Several High Falles, Broken Descending Heads |

|

Ascending |

Rising Head |

Climbing Head |

|

|

Level |

Medium Level Head |

Low Level Head, High Level Head |

|

|

Nuclear and Terminal Tones |

Low (Medium) Fall, Low Rise, Mid-Level |

High Fall, High Rise, Rise-Fall, Fall-Rise, Rise-Fall-Rise |

|

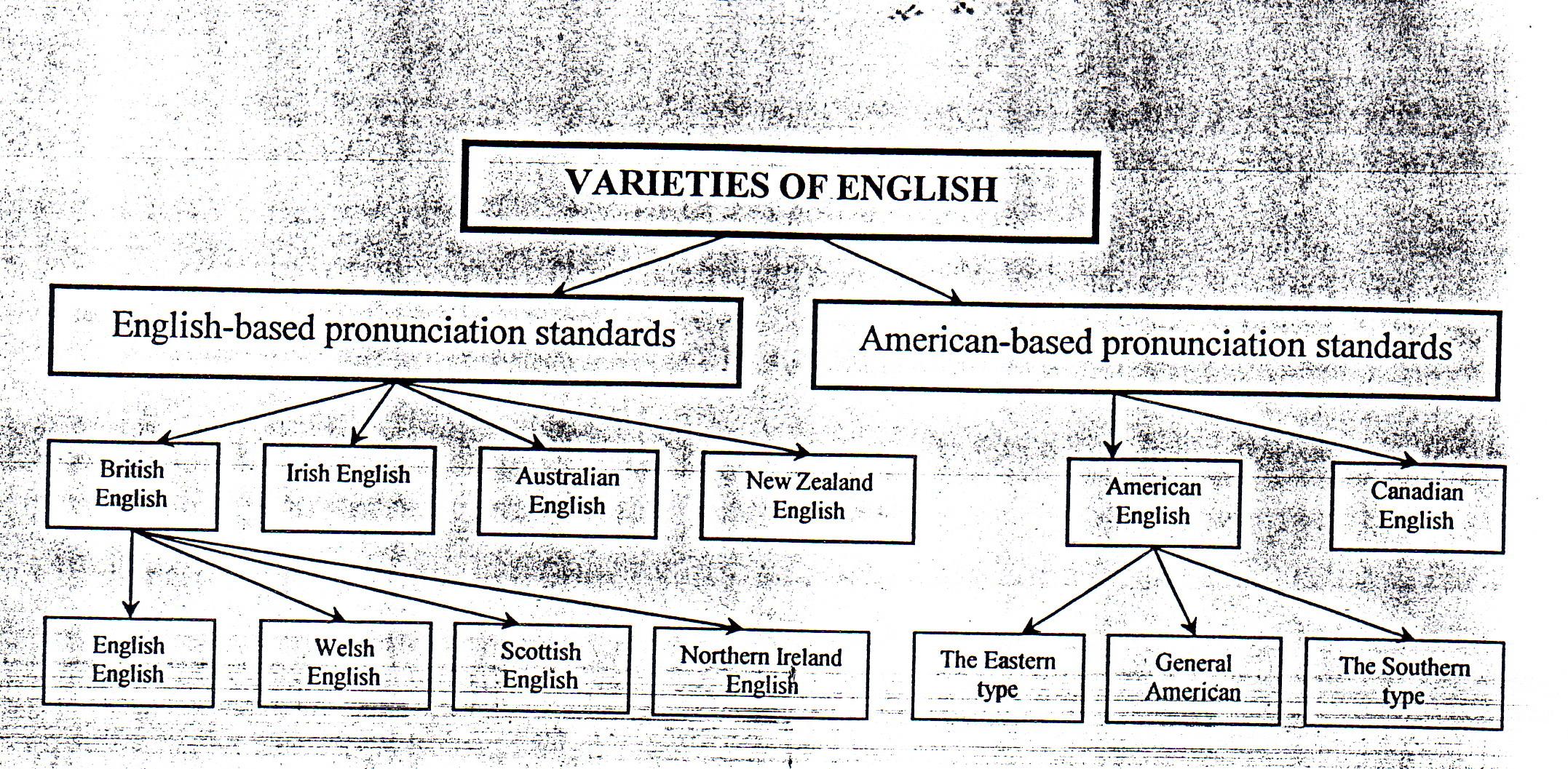

Territorial, social and stylistic varieties of English pronunciation.

The written form of language is usually a generally accepted standard and is the same throughout the country. The varieties of the language are conditioned by language communities ranging from small groups to nations. It’s clear that dialectology is inseparably connected with sociolinguistics, which deals with language variations caused by social difference and different social needs. Sociolinguistics is a branch of linguistics which studies differen aspects of the language – phonetics, lexics and grammar with reference to their functions in the society.

But spoken language may also vary from place to place. Such territorial distinct forms of language are called dialects.

Speaking about the nations we refer to the national variants of the language. According to A.D. Schweitzer national language is a historical category evolving from conditions of economic and political concentration which characterizes the formation of nation. In the case of English there exists a great diversity in the realization of the language and particularly in terms of pronunciation. Though every national variant of English has considerable differences in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar; they all have much in common which gives us ground to speak of one and the same language — the English language.

Every national variety of language falls into territorial or regional dialects. Dialects are distinguished from each other by differences in pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. But pronunciation, above all, is subject to all kinds of changes. Therefore the national variants of English differ primaraly in sound, stress and intonation. When we refer to varieties in pronunciation only, we use the term accent. So local accents may have many features of pronunciation in common and are grouped into territorial or area accents. For certain reasons one of the dialects becomes the standard language of the nation and its pronunciation or accent - the standard pronunciation.

The literary spoken form has its national pronunciation standard. A standard may be defined as "a socially accepted variety of language established by a codified norm of correctness" (K. Macanalay). Standard national pronunciation is sometimes called "an orthoepic norm''. Some phoneticians however prefer the term "literary pronunciation". It’s generally accepted that for the English English It’s called “Received Pronunciation” or RP, for the American English it’s called “General American Pronunciation”, for The Australian English it’s “Educated Australian”. It’s due to certain geografical, economic, political and cultural reasons, that one of the dialects in a country becomes the standart language of the nation.

We have mentioned the vertical – social – diferentiarions of the language. are observed in relation to territorial criterion plus according to the individuelity of the speaker, his cultural values, sex and age differences. Individual speech of members of the society is thus called idiolects. The horisontal differentiations of the language are also occuring because of the situational variability. Hence situational varieties of the language are called functional dialects or functional styles.

Types and styles of pronunciation.

Styles of speech or pronunciation are those special forms of speech suited to the aim and the contents of the utterance, the circumstances of communication, the character of the audience, etc. As D. Jones points out, a person may pronounce the same word or sequence of words quite differently under different circumstances.

In other words, all speakers use more than one style of pronunciation, and variations in the pronunciation of speech sounds, words and sentences peculiar to different styles of speech may be called stylistic variations.

Several different styles of pronunciation may be distinguished, although no generally accepted classification of styles of pronunciation has been worked out and the peculiarities of different styles have not yet been sufficiently investigated.

D. Jones distinguishes among different styles of pronunciation the rapid familiar style, the slower colloquial style, the natural style used in addressing a fair-sized audience, the acquired style of the stage, and the acquired style used in singing.

L.V. Shcherba wrote of the need to distinguish a great variety of styles of speech, in accordance with the great variety of different social occasions and situations, but for the sake of simplicity he suggested that only two styles of pronunciation should be distinguished: (1) colloquial style characteristic of people's quiet talk, and (2) full style, which we use when we want to make our speech especially distinct and, for this purpose, clearly articulate all the syllables of each word.

The kind of style used in pronunciation has a definite effect on the phonemic and allophonic composition of words. More deliberate and distinct utterance results in the use of full vowel sounds in some of the unstressed syllables. Consonants, too, uttered in formal style, will sometimes disappear in colloquial. It is clear that the chief phonetic characteristics of the colloquial style are various forms of the reduction of speech sounds and various kinds of assimilation. The degree of reduction and assimilation depends on the tempo of speech.

S.M. Gaiduchic distinguishes five phonetic styles: solemn (торжественный), "scientific business (научно-деловой), official business (официально-деловой), everyday (бытовой), and familiar (непринужденный). As we may see the above-mentioned phonetic styles on the whole correlate with functional styles of the language. They are differentiated on the basis of spheres of discourse.

The division is usually based on different degrees of formality or rather familiarity between the speaker and the listener. Within each style subdivisions are observed.

There are five intonational styles singled out mainly according to the purpose of communication and to which we could refer all the main varieties of the texts. They are as follows:

-

Informational style.

-

Academic style (Scientific).

-

Publicistic style.

-

Declamatory style (Artistic).

-

Conversational style (Familiar).

But differentiation of intonation according to the purpose of communication is not enough; there are other factors that affect intonation in various situations. Besides any style is seldom realized in its pure form.

Classification of pronunciation variants of British English.

It is common knowledge that over 300 million people now speak English as a first language. It is the national language of Great Britain, the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.

Nowadays two main types of English are spoken in the English-speaking world: British English and American English.

According to British dialectologists (P. Trudgill, J. Hannah, A. Hughes and others), the following variants of English are referred to the English-based group: English English, Welsh English, Australian English, New Zealand English; to the American-based group: United States English, Canadian English. Scottish English and Ireland English fall somewhere between the two, being somewhat by themselves. With Scottish and Irish Somewhere between the two groups by themselves.

According to M. Sokolova and others, English English, Welsh English, Scottish English and Northern Irish English should be better combined into the British English subgroup, on the ground of political, geographical, cultural unity which brought more similarities - then differences for those variants of pronunciation.

So, BEPS (British English Pronunciation Standarts and Accents) comprise four variations plus each of them has its own deviating accents – dialects.

|

English English |

Welsh English |

Scottish English |

Northern Ireland English |

||

|

Southern |

Northern |

|

Educated Sc. Eng. |

Regional Varieties |

|

|

Southern East Anglia South-West |

Northern Yorkshire North-West West Midland |

|

|

|

|

In the nineteenth century Received Pronunciation (RP) was a social marker, a prestige accent of an Englishman. "Received" was understood in the sense of "accepted in the best society". The speech of aristocracy and the court phonetically was that of the London area. Then it lost its local characteristics and was finally fixed as a ruling-class accent, often referred to as "King's English". It was also the accent taught at public schools. With the spread of education cultured people not belonging to upper classes were eager to modify their accent in the direction of social standards. RP is widely regarded as a model for correct pronunciation, particularly for educated formal speech.

It’s stated that RP is regionless – if speakers have it you cannot tell which regions they come from. But only 3-5% of the Population of England speak it. It is also not homogenious and there are three main types within it:

-

Conservative RP – is used by the older generation and by certain profession or social groups.

-

General RP – most commonly in used and typified by the pronunciation adopted by the BBC.

-

Advanced RP – mainly used by young people of exlusive social groups (upper classes) and also in certain professional circles. It reflects the tendencies typical of changes in pronunciation, some of which are results of temporary fashion, some become adopted as a norm.

-

Near-RP southern – the pronunciation of teachers of English and professors of colleges and universities particulary from the South and South-East of England.

English English (Southern and Northern) – 220-223

The division into Southern and Northern

Welsh Englisg – 227

Scottish English – 228-229

Northern Ireland English – 230-232

The term Cockney has both geographical and linguistic associations. Geographically and culturally, it often refers to working class Londoners, particularly those in the East End. Linguistically, it refers to the form of English spoken by this group.

The earliest recorded use of the term is 1362 in and it is used to mean a small, misshapen egg, from Middle English coken (of cocks) and ey (egg) so literally 'a cock's egg'. In the Reeve's Tale by Geoffrey Chaucer (circa 1386) it appears as "cokenay", and the meaning is "a child tenderly brought up, an effeminate fellow, a milksop". By 1521 it was in use by country people as a derogatory reference for the effeminate town-dwellers.

-

As with many accents of England, Cockney is non-rhotic. A final -er is pronounced [ə] or lowered [ɐ] in broad Cockney. As with all or nearly all non-rhotic accents, the paired lexical sets commA and lettER, PALM/BATH and START, THOUGHT and NORTH/FORCE, are merged.

-

Broad /ɑː/ is used in words such as bath, path, demand. This originated in London in the 16h-17th centuries and is also part of Received Pronunciation.

-

T-glottalisation: Use of the glottal stop as an allophone of /t/ in various positions, including after a stressed syllable. Glottal stops also occur, albeit less frequently for /k/ and /p/, and occasionally for mid-word consonants. For example, spelt "Hyde Park" as Hy' Par' . Like and light can be homophones. "Clapham" can be said as Cla'am. /t/ may also be flapped intervocalically. London /p, t, k/ are often aspirated in intervocalic and final environments, e.g., upper, utter, rocker, up, out, rock, where RP is traditionally described as having the unaspirated variants. Also, in broad Cockney at least, the degree of aspiration is typically greater than in RP, and may often also involve some degree of affrication. Affrication may be encountered in initial, intervocalic, and final position.

-

Th-fronting:

-

/θ/ can become [f] in any environment. [fɪn] "thin", [mɛfs] "maths".

-

/ð/ can become [v] in any environment except word-initially when it can be [ð, ð̞, d, l, ʔ, ∅]. [dæɪ] "they", [bɒvə] "bother".

-

-

H-dropping. Sivertsen considers that [h] is to some extent a stylistic marker of emphasis in Cockney.

-

Diphthong alterations:

-

/iː/ → [əi~ɐi]: [bəiʔ] "beet"

-

/eɪ/ → [æɪ~aɪ]: [bæɪʔ] "bait"

-

/aɪ/ → [ɑɪ] or even [ɒɪ] in "vigorous, dialectal" Cockney. The second element may be reduced or absent (with compensatory lengthening of the first element), so that there are variants like [ɑ̟ə~ɑ̟ː]. This means that pairs such as laugh-life, Barton-biting may become homophones: [lɑːf], [bɑːʔn̩]. But this neutralisation is an optional, recoverable one.: [bɑɪʔ] "bite"

-

/ɔɪ/ → [ɔ̝ɪ~oɪ]: [tʃoɪs] "choice"

-

/uː/ → [əʉ] or a monophthongal [ʉː], perhaps with little lip rounding, [ɨː] or [ʊː]: [bʉːʔ] "boot"

-

/əʊ/ → this diphthong typically starts in the area of the London /ʌ/, [æ ̠~ɐ]. The endpoint may be [ʊ], but more commonly it is rather opener and/or lacking any lip rounding, thus being a kind of centralized [ɤ̈]. The broadest Cockney variant approaches [aʊ].: [kʰɐɤ̈ʔ] "coat"

-

/aʊ/ may be [æə] or a monophthongal [æː~aː]: [tʰæən] "town"

-

-

Other vowel differences include

-

/æ/ may be [ɛ] or [ɛɪ], with the latter occurring before voiced consonants, particularly before /d/: [bɛk] "back", [bɛːɪd] "bad"

-

/ɛ/ may be [eə], [eɪ], or [ɛɪ] before certain voiced consonants, particularly before /d/: [beɪd] "bed"

-

/ɜː/ is on occasion somewhat fronted and/or lightly rounded, giving Cockney variants such as [ɜ̟ː], [œ̈ː].

-

/ʌ/ → [ɐ̟] or a quality like that of cardinal 4, [a]: [dʒamʔˈtˢapʰ] "jumped up"

-

/ɔː/ → [oː] or a closing diphthong of the type [oʊ~ɔo] when in non-final position, with the latter variants being more common in broad Cockney: [soʊs] "sauce"-"source", [loʊd] "lord", [ˈwoʊʔə] "water"

-

/ɔː/ → [ɔː] or a centring diphthong of the type [ɔə~ɔwə] when in final position, with the latter variants being more common in broad Cockney; thus [sɔə] "saw"-"sore"-"soar", [lɔə] "law"-"lore", [wɔə] "war"-"wore". The diphthong is retained before inflectional endings, so that board and pause can contrast with bored [bɔəd] and paws [pɔəz]

-

In broad Cockney, and to some extent in general popular London speech, a vocalised /l/ is entirely absorbed by a preceding /ɔː/: i.e., salt and sort become homophones (although the contemporary pronunciation of salt /sɒlt/ would prevent this from happening), and likewise fault-fought-fort, pause-Paul's, Morden-Malden, water-Walter.

-

A preceding /ə/ is also fully absorbed into vocalised /l/. The reflexes of earlier /əl/ and earlier /ɔː(l)/ are thus phonetically similar or identical; speakers are usually ready to treat them as the same phoneme. Thus awful can best be regarded as containing two occurrences of the same vowel, /ˈɔːfɔː/. The difference between musical and music-hall, in an H-dropping broad Cockney, is thus nothing more than a matter of stress and perhaps syllable boundaries.

-

According to Siversten, /ɑː/ and /aɪ/ can also join in this neutralisation. They may on the one hand neutralise with respect to one another, so that snarl and smile rhyme, both ending [-ɑɤ], and Child's Hill is in danger of being mistaken for Charles Hill; or they may go further into a fivefold neutralisation with the one just mentioned, so that pal, pale, foul, snarl and pile all end in [-æɤ]. But these developments are evidently restricted to broad Cockney, not being found in London speech in general.

-

A neutralisation discussed by Beaken (1971) and Bowyer (1973), but ignored by Siversten (1960), is that of /ɒ~əʊ~ʌ/. It leads to the possibility of doll, dole and dull becoming homophonous as [dɒʊ] or [da̠ɤ]. Wells' impression is that the doll-dole neutralisation is rather widespread in London, but that involving dull less so.

-

One further possible neutralisation in the environment of a following non-prevocalic /l/ is that of /ɛ/ and /ɜː/, so that well and whirl become homophonous as [wɛʊ].

-

-

Cockney has been occasionally described as replacing /r/ with /w/. For example, thwee instead of three, fwasty instead of frosty.

Most of the features mentioned above have, in recent years, partly spread into more general south-eastern speech, giving the accent called Estuary English; an Estuary speaker will use some but not all of the Cockney sounds. Some of the features may derive from the upper-class pronunciation of late 18th century London, such as the use of "ain't" for "isn't" and the now lost reversal of "v" and "w".

The Cockney accent has long been looked down upon and thought of as inferior. On the other hand, the Cockney accent has been more accepted as an alternative form of the English Language rather than an 'inferior' one.

Estuary English is a dialect of English widely spoken in South East England, especially along the River Thames and its estuary. The name comes from the area around the Thames, particularly London, Kent, north Surrey and south Essex.

The variety consists of some (but not all) phonetic features of working-class London speech spreading at various rates socially into middle-class speech.

Estuary English is characterised by the following features:

-

Non-rhoticity.

-

Use of intrusive R.

-

A broad A (ɑː) in words such as bath, grass, laugh, etc.

-

/t/ as a glottal stop instead of an alveolar stop, e.g. water (pronounced /wɔːʔə/).

-

Yod-coalescence, i.e., the use of the affricates [dʒ] and [tʃ] instead of the clusters [dj] and [tj] in words like dune and Tuesday. Thus, these words sound like June and choose day, respectively.

Despite the similarity between the two dialects, the following characteristics of Cockney pronunciation are generally not considered to be present in Estuary English:

-

H-dropping, i.e., Dropping [h] in stressed words (e.g. [æʔ] for hat)

-

Replacement of [ɹ] with [ʋ] is not found in Estuary, and is also very much in decline amongst Cockney speakers.

/r/ phoneme is realized as a labiodental approximant [ʋ] in contrast to an alveolar approximant [ɹ]. To speakers who are not used to [ʋ], this can sound like a /w/. Despite being stigmatized, use of labiodental /r/ is increasing in many accents of British English.

R-labialization leads to pronunciations such as the following:

red - [ʋɛd] ring - [ʋɪŋ] rabbit - [ʋæbɪt] merry Christmas - [mɛʋi kʋɪsmɪs]

However, the boundary between Estuary English and Cockney is far from clear-cut.

Estuary English is widely encountered throughout the south and south-east of England, particularly among the young. Many consider it to be a working-class accent, though it is by no means limited to the working class.

Some people adopt the accent as a means of "blending in", appearing to be more working class, or in an attempt to appear to be "a common man" – sometimes this affectation of the accent is derisively referred to as "Mockney". A move away from traditional RP is almost universal among middle class young people.

The term "Estuary English" is a euphemism for a milder variety of the "London Accent".

American English is a set of dialects of the English language used mostly in the United States. The use of English in the United States was a result of British colonization. The first wave of English-speaking settlers arrived in North America in the 17th century. Since then, American English has been influenced by the languages of the Native American population, the languages of European and non-European colonists, immigrants and neighbors, and the languages of slaves from West Africa.

While written AmE is standardized across the country, there are several recognizable variations in the spoken language, both in pronunciation and in vernacular vocabulary. General American is the name given to any American accent that is relatively free of noticeable regional influences. It is known to be the pronunciation standart.

So, Americal English shows lesser degree of diealect than British English. There are onlu three types of educated American speech: The Eastern type, the Southern type and the Western or General American or Northen American.

Most North American speech is rhotic, as English was in most places in the 17th century. In most varieties of North American English, the sound corresponding to the letter r is a retroflex [ɻ] or alveolar approximant [ɹ] rather than a trill or a tap. The loss of syllable-final r in North America is confined mostly to the accents of eastern New England, New York City. In rural tidewater Virginia and eastern New England, 'r' is non-rhotic in accented (such as "bird", "work", "first", "birthday") as well as unaccented syllables, although this is declining among the younger generation of speakers. Furthermore, the er sound of fur or butter, is realized in AmE as a monophthongal r-colored vowel (stressed [ɝ] or unstressed [ɚ]). This does not happen in the non-rhotic varieties of North American speech.

Some other English changes in which most North American dialects do not participate:

-

The shift of /æ/ to /ɑ/ (the so-called "broad A") before /f/, /s/, /θ/, /ð/, /z/, /v/ alone or preceded by a homorganic nasal. This is the difference between the British Received Pronunciation and American pronunciation of bath and dance. In the United States, only eastern New England speakers took up this modification, although even there it is becoming increasingly rare.

-

The realization of intervocalic /t/ as a glottal stop [ʔ] (as in [bɒʔəl] for bottle). This change is not universal for British English and is not considered a feature of Received Pronunciation. This is not a property of most North American dialects.

On the other hand, North American English has undergone some sound changes not found in other varieties of English speech:

Like, there is no strict division of vowels into long and short. Another general and very peculiar feature of pronunciation of vowels is their nasalisation when thei are preceded or followed by a nasal consonant: small, name.

-

The merger of /ɑ/ and /ɒ/, making father and bother rhyme. This change is nearly universal in North American English, occurring almost everywhere except for parts of eastern New England, hence the Boston accent.

-

The merger of /ɑ/ and /ɔ/. This is the so-called cot–caught merger, where cot and caught are homophones.

-

Dropping of /j/ is more extensive than in RP. In most North American accents, /j/ is dropped after all alveolar and interdental consonant, so that new, duke, Tuesday, resume are pronounced /nu/, /duk/, /tuzdeɪ/, /ɹɪzum/.

-

æ-tensing in environments that vary widely from accent to accent; for example, for many speakers, /æ/ is approximately realized as [eə] before nasal consonants. In some accents [æ] and [eə] contrast sometimes, as in Yes, I can [kæn] vs. tin can [keən].

-

The flapping of intervocalic /t/ and /d/ to alveolar tap [ɾ] before unstressed vowels (as in butter, party) and syllabic /l/ (bottle), as well as at the end of a word or morpheme before any vowel (what else, whatever). Thus, for most speakers, pairs such as ladder/latter, metal/medal, and coating/coding are pronounced the same.

-

Both intervocalic /nt/ and /n/ may be realized as [n] or [ɾ̃], making winter and winner homophones. Most areas in which /nt/ is reduced to /n/.

-

The pin-pen merger, by which [ɛ] is raised to [ɪ] before nasal consonants, making pairs like pen/pin homophonous. This merger originated in Southern American English.

-

[r] is articulated with greater retroflaction than the British one (the tip of the tongue is curled futher)

Also, there are differencies in pronunciation of individual words: either [i:], schedule [sk],tomato [ei].

There are many stress differencies: in words of French origine the stress is on the last syllable while in RP it’s on the first one (ballet RP[′bæleı] GA[bæ′leı]). Then: ‘address, ‘cigarette, ‘magasine, ‘adult, ‘inquiry,’research, ‘weekend, ‘ice-cream.

The intonation is slightly different, too. The differencies mostly concern the direction of the voice pitch and the realization of the terminal tones. In GA the voice doesn’t fall to the bottom. This is why the English speech for Americans sounds “affected” or “pretentious” or “sophisticated”. And for the English, Americans sound “dull”, “monotonous” and “indifferent”.

Theoretical Phonetics.

Seminars.

1. Modification of consonants and vowels in connected speech

The three stages in the articulation of a sound.

The ways of joining sounds (merging of stages, interpenetration of stages).

The junctions of consonants (loss of plosion, incomplete plosion, nasal plosion, lateral plosion). Progressive, regressive and double (reciprocal) assimilation.

Assimilation affecting the work of the vocal folds; the active organ of speech; the manner of noise production; both: the place of articulation and the manner of noise production. Accommodation.

Historical and contemporary elision.

Essential weak and contracted forms in English.

Degrees of reduction of the unstressed vowels in English (qualitative, quantitative, zero).

The role of the neutral vowel in the system of the unstressed vocalism in English.

The peculiar features of the unstressed vocalism in English and in Russian.

2. Differences in the articulation bases of English and Russian consonants and vowels.

3. British types of pronunciation.

RP, Estuary English, Cockney and their phonetic peculiarities.

Social and situational variation in British pronunciation.

The main tendencies in modern British pronunciation.

English dialects.

4. The main phonetic peculiarities of American English

General American (GA).

American dialects.