- •Overview

- •Preface

- •Translator’s Note

- •Contents

- •1. Fundamentals

- •Microscopic Anatomy of the Nervous System

- •Elements of Neurophysiology

- •Elements of Neurogenetics

- •General Genetics

- •Neurogenetics

- •Genetic Counseling

- •2. The Clinical Interview in Neurology

- •General Principles of History Taking

- •Special Aspects of History Taking

- •3. The Neurological Examination

- •Basic Principles of the Neurological Examination

- •Stance and Gait

- •Examination of the Head and Cranial Nerves

- •Head and Cervical Spine

- •Cranial Nerves

- •Examination of the Upper Limbs

- •Motor Function and Coordination

- •Muscle Tone and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Trunk

- •Examination of the Lower Limbs

- •Coordination and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

- •Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Examination

- •Psychopathological Findings

- •Neuropsychological Examination

- •Special Considerations in the Neurological Examination of Infants and Young Children

- •Reflexes

- •4. Ancillary Tests in Neurology

- •Fundamentals

- •Imaging Studies

- •Conventional Skeletal Radiographs

- •Computed Tomography (CT)

- •Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- •Angiography with Radiological Contrast Media

- •Myelography and Radiculography

- •Electrophysiological Studies

- •Fundamentals

- •Electroencephalography (EEG)

- •Evoked potentials

- •Electromyography

- •Electroneurography

- •Other Electrophysiological Studies

- •Ultrasonography

- •Other Ancillary Studies

- •Cerebrospinal Fluid Studies

- •Tissue Biopsies

- •Perimetry

- •5. Topical Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Muscle Weakness and Other Motor Disturbances

- •Sensory Disturbances

- •Anatomical Substrate of Sensation

- •Disturbances of Consciousness

- •Dysfunction of Specific Areas of the Brain

- •Thalamic Syndromes

- •Brainstem Syndromes

- •Cerebellar Syndromes

- •6. Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Congenital and Perinatally Acquired Diseases of the Brain

- •Fundamentals

- •Special Clinical Forms

- •Traumatic Brain injury

- •Fundamentals

- •Traumatic Hematomas

- •Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury

- •Intracranial Pressure and Brain Tumors

- •Intracranial Pressure

- •Brain Tumors

- •Cerebral Ischemia

- •Nontraumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

- •Infectious Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Brain

- •Intracranial Abscesses

- •Congenital Metabolic Disorders

- •Acquired Metabolic Disorders

- •Diseases of the Basal Ganglia

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases Causing Hyperkinesia

- •Other Types of Involuntary Movement

- •Cerebellar Diseases

- •Dementing Diseases

- •The Dementia Syndrome

- •Vascular Dementia

- •7. Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Anatomical Fundamentals

- •The Main Spinal Cord Syndromes and Their Anatomical Localization

- •Spinal Cord Trauma

- •Spinal Cord Compression

- •Spinal Cord Tumors

- •Myelopathy Due to Cervical Spondylosis

- •Circulatory Disorders of the Spinal Cord

- •Blood Supply of the Spinal Cord

- •Arterial Hypoperfusion

- •Impaired Venous Drainage

- •Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia

- •Diseases Mainly Affecting the Long Tracts of the Spinal Cord

- •Diseases of the Anterior Horns

- •8. Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

- •Fundamentals

- •Myelin

- •Multiple Sclerosis

- •Other Demyelinating Diseases of Unknown Pathogenesis

- •9. Epilepsy and Its Differential Diagnosis

- •Types of Epilepsy

- •Classification of the Epilepsies

- •Generalized Seizures

- •Partial (Focal) Seizures

- •Status Epilepticus

- •Episodic Neurological Disturbances of Nonepileptic Origin

- •Episodic Disturbances with Transient Loss of Consciousness and Falling

- •Episodic Loss of Consciousness without Falling

- •Episodic Movement Disorders without Loss of Consciousness

- •10. Polyradiculopathy and Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •Polyradiculitis

- •Cranial Polyradiculitis

- •Polyradiculitis of the Cauda Equina

- •Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •11. Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve)

- •Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

- •Visual Field Defects

- •Impairment of Visual Acuity

- •Pathological Findings of the Optic Disc

- •Disturbances of Ocular and Pupillary Motility

- •Fundamentals of Eye Movements

- •Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Supranuclear Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Nerves to the Eye Muscles and Their Brainstem Nuclei

- •Ptosis

- •Pupillary Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve

- •Lesions of the Facial Nerve

- •Disturbances of Hearing and Balance; Vertigo

- •Neurological Disturbances of Hearing

- •Disequilibrium and Vertigo

- •The Lower Cranial Nerves

- •Accessory Nerve Palsy

- •Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy

- •Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits

- •12. Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Spinal Radicular Syndromes

- •Peripheral Nerve Lesions

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases of the Brachial Plexus

- •Diseases of the Nerves of the Trunk

- •13. Painful Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Painful Syndromes of the Head And Neck

- •IHS Classification of Headache

- •Approach to the Patient with Headache

- •Migraine

- •Cluster Headache

- •Tension-type Headache

- •Rare Varieties of Primary headache

- •Symptomatic Headache

- •Painful Syndromes of the Face

- •Dangerous Types of Headache

- •“Genuine” Neuralgias in the Face

- •Painful Shoulder−Arm Syndromes (SAS)

- •Neurogenic Arm Pain

- •Vasogenic Arm Pain

- •“Arm Pain of Overuse”

- •Other Types of Arm Pain

- •Pain in the Trunk and Back

- •Thoracic and Abdominal Wall Pain

- •Back Pain

- •Groin Pain

- •Leg Pain

- •Pseudoradicular Pain

- •14. Diseases of Muscle (Myopathies)

- •Structure and Function of Muscle

- •General Symptomatology, Evaluation, and Classification of Muscle Diseases

- •Muscular Dystrophies

- •Autosomal Muscular Dystrophies

- •Myotonic Syndromes and Periodic Paralysis Syndromes

- •Rarer Types of Muscular Dystrophy

- •Diseases Mainly Causing Myotonia

- •Metabolic Myopathies

- •Acute Rhabdomyolysis

- •Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

- •Myositis

- •Other Diseases Affecting Muscle

- •Myopathies Due to Systemic Disease

- •Congenital Myopathies

- •Disturbances of Neuromuscular Transmission−Myasthenic Syndromes

- •15. Diseases of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Anatomy

- •Normal and Pathological Function of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Sweating

- •Bladder, Bowel, and Sexual Function

- •Generalized Autonomic Dysfunction

- •Index

207

12Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

Fundamentals . . . 207

Spinal Radicular Syndromes . . . 207

Peripheral Nerve Lesions . . . 216

Fundamentals

Lesions of the peripheral nervous system cause flaccid weakness, sensory deficits, and autonomic disturbances in variable distributions and combinations depending on their localization and extent. They can be classified as lesions of the spinal nerve roots (radicular lesions), plexus lesions, or lesions of individual peripheral nerve trunks or branches.

Spinal Radicular Syndromes

Radicular lesions are usually due to mechanical compression; less commonly, they may be infectious/inflammatory or traumatic. Their main clinical manifestation is pain, usually accompanied by a sensory deficit in the dermatome of the affected nerve root. Depending on the severity of the lesion, there may also be flaccid weakness and areflexia in the muscle(s) innervated by the nerve root.

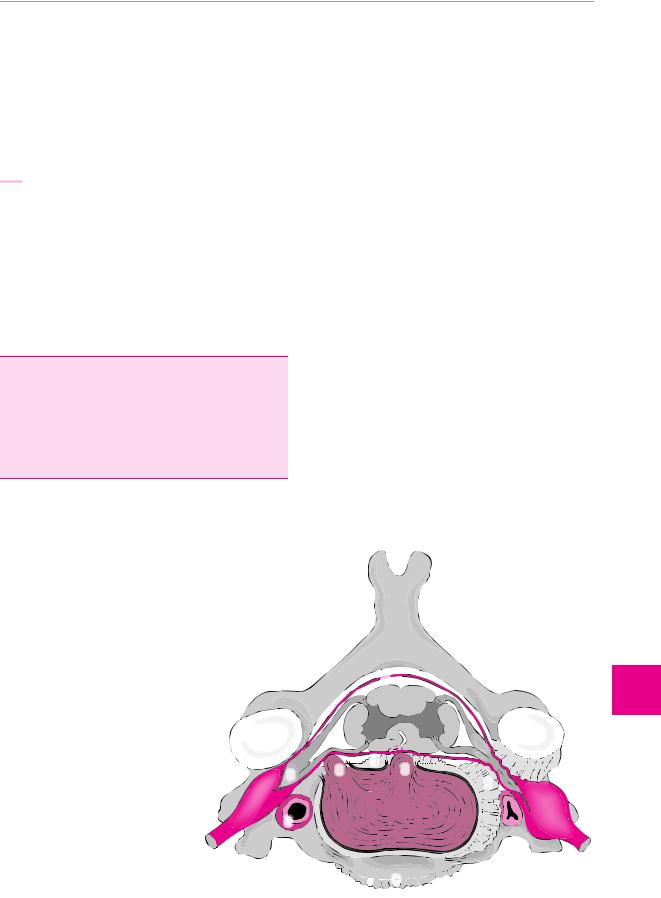

Fig. 12.1 View of a cervical vertebra and intervertebral disk. The normal anatomy of the intervertebral (neural) foramen is shown on the left side of the figure; narrowing of the foramen by uncarthrosis is shown on the right. 1 Facets of the intervertebral joint; 2 root with spinal ganglion; 3 lateral/medial intervertebral disk herniation; 4 vertebral arteries; 5 uncarthrosis; 6 dorsal spondylosis; 7 ventral spondylosis; 8 spinal dura mater. (Modified from Mumenthaler M.: Der Schulter−Arm−Schmerz, 2nd edn, Huber, Bern 1982.)

Preliminary anatomical remarks. The spinal nerve roots constitute the initial segment of the peripheral nervous system. The anterior (ventral) nerve roots contain efferent fibers, while the posterior (dorsal) nerve roots contain afferent fibers. The motor roots from T2 to L2 or L3 also contain the efferent fibers of the sympathetic nervous system. The anterior and posterior roots at a single level of the spinal cord on one side join to form the spinal nerve at that level, which then passes out of the spinal canal through the corresponding intervertebral foramen. At this point, the nerve roots are in close proximity to the intervertebral disk and the intervertebral (facet) joint (Fig. 12.1).

In their further course, the fibers of the spinal nerve roots of multiple segments form plexuses, from which they are then distributed to the peripheral nerves. The areas innervated by the nerve roots thus differ from those innervated by the peripheral nerves.

The sensory component of a spinal nerve root innervates a characteristic segmental area of skin, which is called a dermatome. The efferent fibers of a spinal nerve root, after redistribution into various peripheral nerves, innervate multiple muscles (the “myotome” of the nerve root at that level). Each muscle, therefore, obtains motor impulses from more than one nerve root, even if it is only innervated by a single peripheral nerve.

8

8

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

12

|

3 |

6 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

4 |

7

7

ThiemeArgoOneBoldthiemeArgoOne

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

208 12 Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

Table 12.1 Synopsis of radicular syndromes

Segment |

Sensory deficit |

Motor deficit |

Reflex deficit |

Remarks |

|

|

|

|

|

C3/4 |

pain and hypalgesia in |

diaphragmatic paresis |

none detectable |

partial diaphragmatic |

|

shoulder region |

or plegia |

|

paresis is more ventral |

|

|

|

|

in C3 lesions, more |

|

|

|

|

dorsal in C4 lesions |

C5 |

pain and hypalgesia on |

|

lateral aspect of shoul- |

|

der over deltoid m. |

C6 |

radial side of arm and |

|

forearm down to |

|

thumb |

C7 |

dorsolateral to C6 der- |

|

matome down to 2nd, |

|

3rd, and 4th fingers |

C8 |

dorsal to C7 derma- |

|

tome, down to little |

|

finger |

L3 |

from greater trochan- |

|

ter crossing over the |

|

anterior aspect to the |

|

medial aspect of the |

|

thigh and knee |

L4 |

from lateral thigh |

|

across patella to upper |

|

inner quadrant of calf |

|

and down to medial |

|

edge of foot |

L5 |

from lateral condyle |

|

above knee across the |

|

upper outer quadrant |

|

of the calf to the great |

|

toe |

S1 |

from posterior thigh |

|

over posterior upper |

|

quadrant of calf and |

|

lateral malleolus to |

|

little toe |

Combined |

combination of L4 and |

L4, L5 |

L5 dermatomes |

Combined |

combination of L5 and |

L5, S1 |

S1 dermatomes |

deltoid and biceps paresis

biceps and brachioradialis paresis

triceps, pronator teres, and (occas.) finger flexor paresis; thenar eminence often visibly atrophic

intrinsic hand muscles visibly atrophic, particularly on hypothenar eminence

quadriceps paresis

quadriceps and tibialis anterior paresis

paresis and atrophy of extensor hallucis longus m., often also of extensor digitorum brevis m.; paresis of tibialis posterior m. and of hip abduction

paresis of the peronei, often also of the gastrocnemius and soleus mm.

paresis of all foot and toe extensors and of quadriceps m.

paresis of toe extensors, peronei, occasional also gastrocnemius and soleus mm.

diminished biceps reflex

diminished or absent biceps reflex

diminished or absent triceps reflex

diminished triceps reflex

weakness of quadriceps (knee-jerk) reflex

weakness of quadriceps reflex

absent tibialis posterior reflex (of diagnostic value only when clearly elicitable on opposite, unaffected side)

absent gastrocnemius reflex (ankle-jerk or Achilles reflex)

triceps reflex key to differential diagnosis vs. carpal tunnel syndrome

triceps reflex key to differential diagnosis vs. ulnar nerve palsy

differential diagnosis vs. femoral nerve palsy: sensation intact in distribution of saphenous n.

differential diagnosis vs. femoral nerve palsy: involvement of tibialis anterior m.

differential diagnosis vs. peroneal nerve palsy: in the latter, tibialis posterior and hip abduction are preserved

diminished quadriceps |

differential diagnosis |

reflex, absent tibialis |

vs. peroneal nerve |

posterior reflex |

palsy: peronei spared. |

|

Note reflex findings |

absent tibialis poste- |

differential diagnosis |

rior and gastrocnemius |

vs. peroneal nerve |

reflexes |

palsy: tibialis anterior |

|

spared. Note reflex fin- |

|

dings |

Table 12.1 lists the muscles that are often affected by radicular lesions in a way that is easily revealed by clinical neurological examination. The muscles that derive most of their innervation from a single nerve root are known as “root-indicating muscles.”

Causes of radicular syndromes. In most patients, the cause is compression of the nerve root by a space-oc- cupying lesion, most often a herniated intervertebral disk, but sometimes a tumor, abscess, or other mass. In the cervical segments, spondylotic narrowing of the in-

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Fundamentals 209

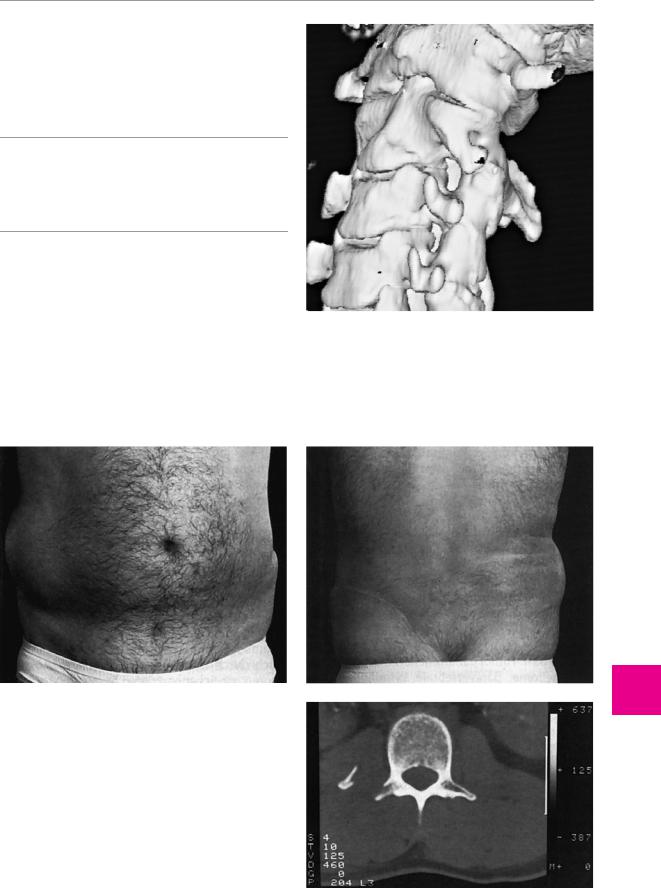

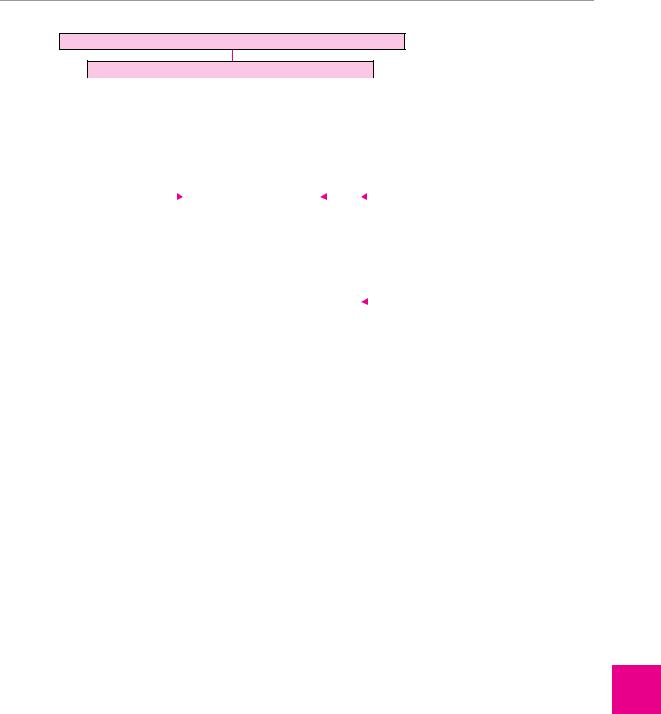

tervertebral foramina, is a further common cause of radicular pain and brachialgia (Fig. 12.2). Infectious and inflammatory processes can cause monoradicular deficits, e. g., herpes zoster and borreliosis (Lyme disease, p. 117). Diabetes mellitus, too, can cause monoradiculopathy with pain and weakness. Finally, traumatic lesions, e. g., bony fractures, can affect individual nerve roots (Fig. 12.3).

!Radiculopathy is often due to a mechanical injury or irritation of a nerve root by degenerative disease of the spine, particularly intervertebral disk herniation. A radicular deficit, however, should never simply be assumed to be due to disk herniation. Other etiologies (see above) must always be considered.

General clinical manifestations of radicular lesions.

Regardless of the etiology, the following symptoms and neurological findings are characteristic:

pain in the distribution of the affected nerve root;

a sensory deficit and irritative sensory phenomena (paresthesia, dysesthesia) in the dermatome of the affected nerve root; in monoradicular lesions, these are easier to bring out by testing with noxious (painful) stimuli, rather than with ordinary somatosensory stimuli;

a

Fig. 12.3 Weakness of the abdominal wall musculature on the right in a 33-year-old man, 7 months after spinal and pelvic trauma. The muscle weakness is evident both from the front (a) and from the back (b). The CT scan (c) reveals a fracture of the right transverse process of a vertebra, which is the cause of the lesion of the motor spinal nerve roots.

ThiemeArgoOneBoldthiemeArgoOne

Fig. 12.2 Stenosis of the left C3/4 intervertebral foramen (3D CT reconstruction).

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

b

12

c

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

210 12 |

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

paresis of the muscle(s) supplied by the affected |

pain on extension (in the lower limb, a positive |

|

|

nerve root, generally less marked than the paresis |

Lasègue sign). |

|

|

caused by a peripheral nerve lesion (no plegia!) be- |

exacerbation of pain by coughing, abdominal |

|

|

cause of the polyradicular innervation of most |

pressing (Valsalva maneuvers), and sneezing. |

|

|

muscles, but possibly severe in the root-indicating |

objectifiable neurological deficits (hyporeflexia or |

|

|

muscles; |

areflexia, paresis, sensory deficit, atrophy in the late |

|

muscle atrophy is common, but usually less severe |

stage; see above) depending on the severity of the |

|

|

|

than in peripheral nerve lesions, while chronic radic- |

root lesion. |

|

|

ular lesions can, rarely, cause fasciculations; |

|

|

impaired reflexes in the segment corresponding to |

Cervical Disk Herniation |

|

|

|

the affected nerve root. |

|

|

|

Cervical disk herniation is a common cause of acute tor- |

|

|

The characteristic syndromes of the individual nerve |

||

|

ticollis and of acute (cervico) brachialgia. |

||

roots supplying the upper and lower limbs are sum- |

|

||

marized in Table 12.1. |

Etiology. Cervical disk herniation may occur as the re- |

||

Differential diagnosis. Radicular syndromes must be |

sult of nuchal trauma, a twisting injury of the cervical |

||

spine, an excessively rapid movement, or mechanical |

|||

|

differentiated from lesions in more distal components of |

overload. |

|

|

the peripheral nervous system (plexuses, peripheral |

|

|

nerves). This can usually be done by careful clinical ex- |

Clinical manifestations. The most commonly affected |

||

|

amination alone, but electromyography may be required |

segments are C6, C7, and C8. Subjectively, patients usu- |

|

for unambiguous confirmation. The lack of an autonomic |

ally complain of pain in the neck and upper limb, and |

||

|

deficit may be a useful clinical criterion in the differential |

sometimes of a sensory deficit, which does not neces- |

|

|

diagnosis of radicular lesions that affect the limbs, be- |

sarily cover the entire zone of innervation of the af- |

|

|

cause sympathetic fibers travel in the spinal nerve roots |

fected root. |

|

|

only at levels T12 through L2 (see above); therefore, an |

|

|

|

autonomic deficit in a limb always indicates a lesion dis- |

Diagnostic evaluation. The clinical history and physical |

|

|

tal to the nerve root. Some of the conditions that enter |

examination should already enable identification of the |

|

into the differential diagnosis of various radicular and |

affected nerve root. The objectively observable neuro- |

||

|

peripheral nerve syndromes are listed in Table 12.1. |

logical deficits are listed in Table 12.1. The Spurling test |

|

|

|

When there is a purely motor deficit, unaccompanied |

can provide further evidence of irritation of a cervical |

|

by a sensory deficit or pain, a lesion of the spinal motor |

nerve root: the head is leaned backward and the face is |

|

neurons (e. g., spinal muscular atrophy or amyotrophic |

turned to the side of the lesion. Carefully titrated axial |

||

lateral sclerosis) should be suspected, rather than a |

compression by the examiner’s hand may induce pain |

||

radicular lesion. If the patient complains only of pain |

radiating in a radicular distribution (Fig. 12.4). Imaging |

||

radiating into the periphery, in the absence of any de- |

studies (CT and/or MRI) are indispensable for the de- |

||

monstrable sensory deficit or weakness, the clinician |

monstration of nerve root compression by a herniated |

||

should think of pseudoradicular pain (p. 261) due to me- |

intervertebral disk. These are sometimes supplemented |

||

|

chanical overuse or other pathology of the |

by neurography (i. e., measurement of nerve conduction |

|

|

musculoskeletal apparatus. |

velocities) and electromyography. One should not forget, |

|

|

however, that a mere disk protrusion without any de- |

|

Radicular Syndromes Due to |

tectable nerve root compression is a common radiologi- |

|

cal finding in asymptomatic persons. |

||

Intervertebral Disk Herniation |

||

|

The proximity of the spinal nerve root to the intervertebral disk at the level of the intervertebral foramen carries with it the danger of root compression by disk herniation. The nerve root can be compressed either by a merely bulging disk or by a disk herniation in the truest sense, i. e., a prolapse of nucleus pulposus material (which is usually soft) through a hole in the annulus fibrosus.

General clinical manifestations. The typical manifestations of acute radiculopathy due to intervertebral disk herniation are the following:

local pain in the corresponding area of the spine, with painful restriction of movement and, sometimes, a compensatory, abnormal posture of the spine (scoliosis, flattening of lordosis).

usually, after a few hours or days, radiation of pain into the cutaneous area of distribution (dermatome) of the affected nerve root.

Treatment. Temporary rest and physical therapy, with the addition of appropriate exercises as soon as the patient can tolerate them, usually suffice as treatment. Sufficient analgesic medication must also be provided, to prevent the chronification of the pain syndrome through the maintenance of an abnormal, antalgic posture (persistent fixation of the affected spinal segments by muscle spasm) and through nonphysiological stress on other muscle groups. If operative treatment is necessary (e. g., because of intractable pain, persistent, severe or progressive paresis, or signs of compression of the spinal cord), then the appropriate treatment is fenestration of the intervertebral space at the appropriate level for exposure of the nerve root and disk, widening of the bony intervertebral foramen (foraminotomy), then diskectomy, and, under some circumstances, spondylodesis (fusion) if there is thought to be a risk of spinal instability afterward. Fusion should be performed in such a way as to distract the vertebrae above and below and thereby maintain the patency of the intervertebral foramen.

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Fundamentals

Lumbar Disk Herniation

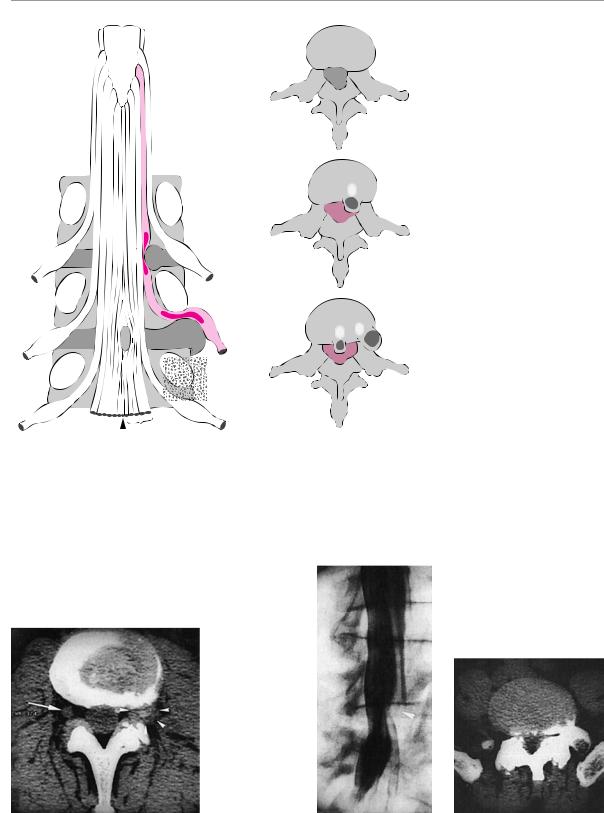

Lumbar disk herniation is one of the more common causes of acute low back pain and sciatica. The anatomical relationship of the lumbar roots to the intervertebral disks (both normal and herniated) is shown schematically in Fig. 12.5.

Clinical manifestations. A first bout of lumbar disk herniation (and often the first or second recurrence as well) may present with no more than acute low back pain (lumbago). The event may be precipitated by a relatively banal movement in the wrong direction; in particular, the lumbar spine may suddenly freeze in a twisted position as the unfortunate individual attempts to lift a heavy load while the upper body is turned to one side. Any further movement of the lumbar spine is blocked by muscle spasm, a reflex response to the pain. Even the smallest movement is painful, as are coughing and abdominal pressing (Valsalva maneuvers). The pain usually resolves after a few days of bed rest. It is usually only when the herniation recurs later that the patient experiences pain radiating into the leg, i. e., sciatica, and possibly in combination with typical radicular neurological deficits.

In our experience, motor deficits generally arise only later in the course of this syndrome. The patient must be examined carefully to determine whether a deficit is present. The L5 root is most commonly affected, usually by an L4−5 disk herniation, and the S1 root is the next most commonly affected after that, usually by an L5−S1 disk herniation. The corresponding clinical findings are listed in Table 12.1.

Diagnostic evaluation. As in cervical disk herniation, the level of the nerve root that is affected can generally be determined from the pattern of referred pain and any motor, sensory, and reflex deficits that may be present. The peripheral nerve trunk containing the axons whose more proximal portions are located in the affected root is often sensitive to pressure (at the Valleix pressure points) and stretching of the nerve is often painful. The latter can be tested by passive raising of the supine patient’s leg, extended at the knee (the Lasègue test). Pain caused by elevation of the leg on the side opposite the sciatica (the crossed Lasègue sign) usually indicates a large, prolapsed disk herniation. If a higher lumbar root (L3 or L4) is affected, one should look for the reverse Lasègue sign, i. e., test for pain on extension of the leg in the prone patient, which stretches the femoral n. rather than the sciatic n. (reverse Lasègue test). If the herniation is lateral or extraforaminal, pain will also be inducible by lateral bending of the trunk.

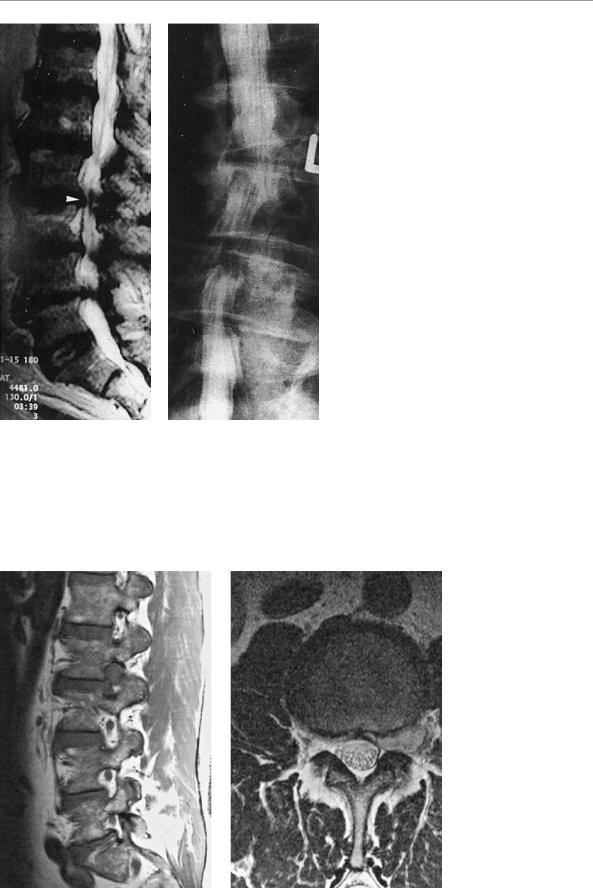

Imaging studies are not absolutely essential if the clinical picture is sufficiently characteristic, but they should be performed if there is any doubt as to the etiology of nerve root compression, or if the situation requires operative intervention. CT is the method of choice if the segmental level of the suspected disk herniation is clinically unambiguous; the main advantage of CT is that it can clearly demonstrate a far lateral disk herniation, if this turns out to be present (Fig. 12.6). It can also reveal bony deformities of the spinal canal and nerve root impingement by spondylotic changes, if present

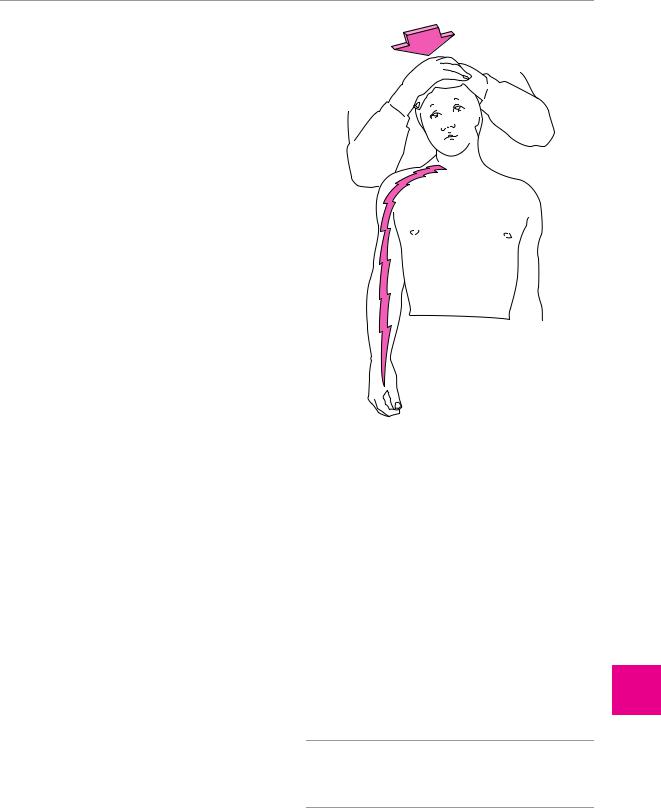

Fig. 12.4 Spurling cervical compression test for the provocation of radicular pain in cervical disk herniation (after Mumenthaler M.: Der Schulter−Arm−Schmerz, 2nd edn, Huber, Bern 1982.) Pain can often be elicited by reclination and rotation of the head toward the affected side even without compression.

(Fig. 12.7). MRI is to be preferred over CT, however, if the level of the lesion is not fully clear on clinical grounds. The images should always be interpreted critically and in consideration of the associated clinical findings.

Neurography and electromyography are sometimes worth performing as supplementary tests.

Treatment. The initial treatment is conservative in practically all patients and is along the same lines as described above for cervical disk herniation. Operative treatment should be considered only if conservative treatment fails.

An incipient cauda equina syndrome (bladder and bowel dysfunction, saddle hypesthesia, bilateral pareses, and impairment of the anal reflex, cf. p. 144) is an absolute indication for urgent surgery.

!When the clinical signs of cauda equina syndrome are present because of lumbar intervertebral disk herniation, an emergency neurosurgical procedure must be performed immediately.

Further indications for operative treatment are set forth in Fig. 12.8. At operation, the herniated disk tissue is removed, and, if there is a danger of postoperative instability at the level being operated on, a fusion (spondylodesis) is performed as well. This is more likely to be the

ThiemeArgoOneBoldthiemeArgoOne

211

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

12

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

212 12 Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

|

Fig. 12.5 Anatomical relationships of |

|

lateral |

the lumbar intervertebral disks to |

|

the exiting nerve roots. |

||

recess |

||

|

||

stenosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

L3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

vertebra |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L3 |

|

|

L4 |

|

|

|

root |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

vertebra |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

||

|

|

|

|

3 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

L4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

L5 |

|

|

|

root |

|

|

vertebra |

|

|

|

|

|

|

coccygeal root |

|

S1–S5 |

|

L5 |

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

roots |

|

|

||

|

|

|

root |

|

||

1 mediolateral prolapse |

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 lateral prolapse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 medial prolapse |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12.6 Lateral L3/4 disk herniation (arrowheads), CT image. The normal spinal ganglion on the right side is visible in the intervertebral foramen (arrow).

a |

b |

Fig. 12.7 Left S1 radicular compression in a 40-year-old man. Myelography (a) reveals a broadened and shortened left S1 nerve root (arrowhead) and an indentation of the dural sack from the right at this level. CT (b) reveals high-grade spondyloarthrosis and bilateral stenosis of the lateral recesses.

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Fundamentals

typical or highly suggestive symptoms of lumbar disk herniation

does the neurological examination reveal a radicular deficit?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

conservative treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

bladder dysfunction? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

improvement |

|

|

no improvement |

|

|

|

|

yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

in 3 weeks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

imaging study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

motor deficit? |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

pathological |

|

|

|

normal |

|

|

|

|

yes, severe |

|

|

|

|

none or mild |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

correlation of radiological |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

conservative treatment |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

and clinical findings? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no improvement |

|

|

improvement |

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

yes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

no |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

in 2 weeks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surgery |

|

|

|

reconsideration of the diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

herniated disk still |

|

|

new diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

considered most likely |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

additional |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

imaging study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12.8 Diagnostic and therapeutic flowchart in lumbar disk herniation.

case in older patients and when the intervertebral disk degeneration is very advanced. As in cervical disk procedures, spondylodesis must be performed in such a way as to keep the vertebral bodies above and below the disk a sufficient distance apart (in distraction), so that the intervertebral foramina are held open.

Radicular Syndromes Due to

Spinal Stenosis

Slowly progressive mechanical compression of the intraspinal neural structures is usually seen in older patients in whom congenital narrowness of spinal canal has been accentuated by further, progressive, degenerative osteochondrotic and reactive-spondylogenic changes.

Cervical Spinal Stenosis

A narrow cervical spinal canal can compress not only the cervical nerve roots, but also the spinal cord itself, producing a myelopathy. Cervical spondylogenic myelopathy is discussed in detail above on p. 147.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

For anatomical reasons, a narrow lumbar spinal canal causes an entirely different clinical syndrome than cervical spinal stenosis:

Clinical manifestations. In addition to low back pain, which is usually chronic, neurogenic intermittent claudication is the most characteristic symptom: as the patient walks, sciatica-like pain arises on the posterior aspect of one or, usually, both lower limbs and then becomes progressively severe. The pain appears earlier if the patient is walking downhill, because of the additional lumbar lordosis that downhill walking induces. This historical feature differentiates neurogenic from vasogenic intermittent claudication, in which the pain tends to be more severe when the patient walks uphill. A further differentiating feature of neurogenic, as opposed to vasogenic, intermittent claudication is that standing still will not, by itself, cause the pain to go away. The patient must additionally bend forward, sit down, or crouch—these maneuvers induce kyphosis of the lumbar spine and thereby decompress its neural contents.

Diagnostic evaluation. Nowadays, the definitive diagnostic study is MRI, though radiculography and myelographic CT are still sometimes needed (Fig. 12.9).

213

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

12

ThiemeArgoOneBoldthiemeArgoOne

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

214 12 Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

a

Treatment. If the symptoms are very severe, and the neurological deficits are progressive, then a treatment option to be considered is operative decompression of the affected segments by opening of the narrowed lateral recesses, possibly in combination with a stabilizing spondylodesis (fusion).

Fig. 12.9 Lumbar disk herniation in a 70-year-old man with neurogenic intermittent claudication due to degenerative lumbar spinal canal stenosis. The MRI (a) and myelogram (b) reveal compression of the dural sac and the nerve roots at the L2−3 (arrow) and L3−4 disk levels, as well as at L4−5 (less severe).

b

Radicular Syndromes Due to

Space-Occupying Lesions

The term “space-occupying lesion,” in its narrowest sense, refers to a tumor. Neurinoma (Fig. 12.10) and meningioma are the most common types of intraspinal

Fig. 12.10 Nerve root neurinoma filling the left L3/4 intervertebral foramen (MR images). Normal nerve roots, free of compression, are seen in the intervertebral foramina above and below the level of the lesion (a). The axial section (b) reveals an hourglassshaped neurinoma, lying partly within and partly outside the spinal canal.

a |

b |

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Fundamentals 215

primary tumor, while ependymoma (Fig. 12.11), glioma (usually astrocytoma), and vascular tumors are rarer. Nerve root lesions can also be caused by a primary destructive process affecting a spinal vertebra (Fig. 12.12), particularly metastatic carcinoma. Finally, infectious and inflammatory processes of the vertebrae and intervertebral disks (e. g., spondylodiscitis), as well as spinal abscesses and empyema, can cause radicular or spinal cord compression.

Clinical manifestations. The patient usually complains of pain radiating into the periphery; if the lesion is at a thoracic level, the pain tends to be in a bandlike distribution around the chest. Motor or sensory deficits may also be clinically detectable, depending on the level of the lesion. A space-occupying lesion within the lower lumbar canal can produce cauda equina syndrome, which may be of greater or lesser severity.

Diagnostic evaluation. Imaging studies are indispensable for diagnosis. If the underlying lesion is a nerve root neurinoma, plain films may already reveal the characteristic, widened intervertebral foramen, e. g., in the cervical region (Fig. 12.13). Nonetheless, CT or MRI (Fig. 12.14) is always necessary to demonstrate the full extent of the tumor.

Treatment. Operative treatment (resection of the lesion) is needed in most patients. Depending on the underlying illness, further treatment may be required (radiotherapy, antineoplastic chemotherapy, or antibiotics after the removal of an abscess or empyema).

Fig. 12.11 Sausage-shaped cystic ependymoma filling the spinal canal from L1 to L3 and compressing the cauda equina (MR image).

a

Fig. 12.12 Metastatic melanoma in the lumbosacral spinal canal, 8 years after resection of the primary tumor: sagittal (a) and axial (b) MR images. The patient presented with cauda equina syndrome.

ThiemeArgoOneBoldthiemeArgoOne

b

The nerve roots of the cauda equina are displaced dorsally and to the left by the compressive lesion.

Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

12

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.