- •Overview

- •Preface

- •Translator’s Note

- •Contents

- •1. Fundamentals

- •Microscopic Anatomy of the Nervous System

- •Elements of Neurophysiology

- •Elements of Neurogenetics

- •General Genetics

- •Neurogenetics

- •Genetic Counseling

- •2. The Clinical Interview in Neurology

- •General Principles of History Taking

- •Special Aspects of History Taking

- •3. The Neurological Examination

- •Basic Principles of the Neurological Examination

- •Stance and Gait

- •Examination of the Head and Cranial Nerves

- •Head and Cervical Spine

- •Cranial Nerves

- •Examination of the Upper Limbs

- •Motor Function and Coordination

- •Muscle Tone and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Trunk

- •Examination of the Lower Limbs

- •Coordination and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

- •Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Examination

- •Psychopathological Findings

- •Neuropsychological Examination

- •Special Considerations in the Neurological Examination of Infants and Young Children

- •Reflexes

- •4. Ancillary Tests in Neurology

- •Fundamentals

- •Imaging Studies

- •Conventional Skeletal Radiographs

- •Computed Tomography (CT)

- •Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- •Angiography with Radiological Contrast Media

- •Myelography and Radiculography

- •Electrophysiological Studies

- •Fundamentals

- •Electroencephalography (EEG)

- •Evoked potentials

- •Electromyography

- •Electroneurography

- •Other Electrophysiological Studies

- •Ultrasonography

- •Other Ancillary Studies

- •Cerebrospinal Fluid Studies

- •Tissue Biopsies

- •Perimetry

- •5. Topical Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Muscle Weakness and Other Motor Disturbances

- •Sensory Disturbances

- •Anatomical Substrate of Sensation

- •Disturbances of Consciousness

- •Dysfunction of Specific Areas of the Brain

- •Thalamic Syndromes

- •Brainstem Syndromes

- •Cerebellar Syndromes

- •6. Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Congenital and Perinatally Acquired Diseases of the Brain

- •Fundamentals

- •Special Clinical Forms

- •Traumatic Brain injury

- •Fundamentals

- •Traumatic Hematomas

- •Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury

- •Intracranial Pressure and Brain Tumors

- •Intracranial Pressure

- •Brain Tumors

- •Cerebral Ischemia

- •Nontraumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

- •Infectious Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Brain

- •Intracranial Abscesses

- •Congenital Metabolic Disorders

- •Acquired Metabolic Disorders

- •Diseases of the Basal Ganglia

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases Causing Hyperkinesia

- •Other Types of Involuntary Movement

- •Cerebellar Diseases

- •Dementing Diseases

- •The Dementia Syndrome

- •Vascular Dementia

- •7. Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Anatomical Fundamentals

- •The Main Spinal Cord Syndromes and Their Anatomical Localization

- •Spinal Cord Trauma

- •Spinal Cord Compression

- •Spinal Cord Tumors

- •Myelopathy Due to Cervical Spondylosis

- •Circulatory Disorders of the Spinal Cord

- •Blood Supply of the Spinal Cord

- •Arterial Hypoperfusion

- •Impaired Venous Drainage

- •Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia

- •Diseases Mainly Affecting the Long Tracts of the Spinal Cord

- •Diseases of the Anterior Horns

- •8. Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

- •Fundamentals

- •Myelin

- •Multiple Sclerosis

- •Other Demyelinating Diseases of Unknown Pathogenesis

- •9. Epilepsy and Its Differential Diagnosis

- •Types of Epilepsy

- •Classification of the Epilepsies

- •Generalized Seizures

- •Partial (Focal) Seizures

- •Status Epilepticus

- •Episodic Neurological Disturbances of Nonepileptic Origin

- •Episodic Disturbances with Transient Loss of Consciousness and Falling

- •Episodic Loss of Consciousness without Falling

- •Episodic Movement Disorders without Loss of Consciousness

- •10. Polyradiculopathy and Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •Polyradiculitis

- •Cranial Polyradiculitis

- •Polyradiculitis of the Cauda Equina

- •Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •11. Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve)

- •Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

- •Visual Field Defects

- •Impairment of Visual Acuity

- •Pathological Findings of the Optic Disc

- •Disturbances of Ocular and Pupillary Motility

- •Fundamentals of Eye Movements

- •Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Supranuclear Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Nerves to the Eye Muscles and Their Brainstem Nuclei

- •Ptosis

- •Pupillary Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve

- •Lesions of the Facial Nerve

- •Disturbances of Hearing and Balance; Vertigo

- •Neurological Disturbances of Hearing

- •Disequilibrium and Vertigo

- •The Lower Cranial Nerves

- •Accessory Nerve Palsy

- •Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy

- •Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits

- •12. Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Spinal Radicular Syndromes

- •Peripheral Nerve Lesions

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases of the Brachial Plexus

- •Diseases of the Nerves of the Trunk

- •13. Painful Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Painful Syndromes of the Head And Neck

- •IHS Classification of Headache

- •Approach to the Patient with Headache

- •Migraine

- •Cluster Headache

- •Tension-type Headache

- •Rare Varieties of Primary headache

- •Symptomatic Headache

- •Painful Syndromes of the Face

- •Dangerous Types of Headache

- •“Genuine” Neuralgias in the Face

- •Painful Shoulder−Arm Syndromes (SAS)

- •Neurogenic Arm Pain

- •Vasogenic Arm Pain

- •“Arm Pain of Overuse”

- •Other Types of Arm Pain

- •Pain in the Trunk and Back

- •Thoracic and Abdominal Wall Pain

- •Back Pain

- •Groin Pain

- •Leg Pain

- •Pseudoradicular Pain

- •14. Diseases of Muscle (Myopathies)

- •Structure and Function of Muscle

- •General Symptomatology, Evaluation, and Classification of Muscle Diseases

- •Muscular Dystrophies

- •Autosomal Muscular Dystrophies

- •Myotonic Syndromes and Periodic Paralysis Syndromes

- •Rarer Types of Muscular Dystrophy

- •Diseases Mainly Causing Myotonia

- •Metabolic Myopathies

- •Acute Rhabdomyolysis

- •Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

- •Myositis

- •Other Diseases Affecting Muscle

- •Myopathies Due to Systemic Disease

- •Congenital Myopathies

- •Disturbances of Neuromuscular Transmission−Myasthenic Syndromes

- •15. Diseases of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Anatomy

- •Normal and Pathological Function of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Sweating

- •Bladder, Bowel, and Sexual Function

- •Generalized Autonomic Dysfunction

- •Index

156

8Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

Fundamentals . . . |

156 |

Other Demyelinating Diseases |

|

Multiple Sclerosis |

. . . 156 |

of Unknown Pathogenesis . . . |

160 |

Fundamentals

The common feature of all diseases affecting myelin is a pathological abnormality or total destruction of myelin sheaths, primarily in the central nervous system. Deficient myelin formation is caused by congenital enzyme defects in a small subgroup of these diseases (the leukodystrophies, p. 121), but, in most of them, myelin is lost later in life, for reasons that are currently not well understood. Immunological (autoimmune) processes and metabolic disturbances appear to play important roles. The most common demyelinating disease is multiple sclerosis.

Myelin

Most axons are surrounded by a myelin sheath. The myelin sheaths of the central nervous system are composed of the cell membrane of oligodendroglia, which is wrapped around the axon to form a multilaminar structure, as seen in the illustration on p. 2.

The myelin sheath enables the axon to conduct impulses more rapidly (see p. 4); thus, loss of myelin lowers conduction velocity, producing clinical manifestations of neuronal dysfunction. The myelination of the central nervous system reaches its final extent in the first few years of postnatal life. Each layer of a myelin sheath is 7.5 microns thick and is composed of two lipoid and two proteinaceous monomolecular layers. In the genetic myelinopathies, the primary development of myelin is deficient; in the metabolic and autoimmune demyelinating diseases, originally intact myelin is attacked and destroyed. The most common demyelinating disease, multiple sclerosis, is described in further detail below.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic disease of the central nervous system. It usually presents with episodic neurological deficits, which, later on in the course of the disease, tend not to reverse fully, leaving increasingly severe residual deficits whose summation causes progressively severe disability.

The clinical manifestations are very diverse because widely separated areas of the CNS are affected and the temporal course of the disease is variable.

“Disseminated encephalomyelitis” is a synonym for multiple sclerosis. In French, the disease is called “sclérose en plaques,” as it was named by Charcot; related terms are used in the other Romance languages.

Epidemiology. The incidence in temperate zones is four to six new cases per 100 000 persons per year and the prevalence is greater than 100 per 100 000. MS is particularly common in northern Europe, Switzerland, Russia, the northern U.S.A., southern Canada, New Zealand, and southwest Australia. Women are affected about four times as commonly as men. The initial attack usually oc-

curs in the second or third decade, only rarely in a child or older adult.

!After ischemic stroke, multiple sclerosis ranks second among all neurological diseases as a cause of chronic disability.

Pathological anatomy. There are disseminated foci of demyelination in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), sometimes with destruction of axons as well. Local, reactive gliosis is found at the sites of older foci. Thus, “sclerosis” develops at “multiple” locations, giving the disease its English name.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenetic mechanisms underlying MS are still poorly understood. The most promising hypothesis at present is that an infection of neurons and glia occurs in childhood, after which the genome of the pathogenic organism remains in the nervous system. The pathogenic genome is then reactivated on multiple occasions through influences of various kinds; this reactivation, in turn, impairs the functioning of the oligodendroglia, producing episodes of demyelination. Ac-

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Multiple Sclerosis

cording to this hypothesis, CNS demyelination and the generation of antibodies against myelin are merely secondary consequences of the disease process, rather than the cause of MS. An effect of the primary infection outside the central nervous system might explain the lymphocyte abnormalities that are also observed in MS.

Another hypothesis is that an infection induces a (cellmediated) autoimmune reaction against normal or virally infected components of the nervous system.

In any case, multiple sclerosis clearly involves a reactive process that can be set in motion by more than one precipitating factor. This explains why foci can arise in such diverse locations in the central nervous system and why the temporal course of the disease is so variable.

Many different exogenous factors have been proposed as putative causes of MS, but no clear causal relationship has yet been demonstrated for any of them.

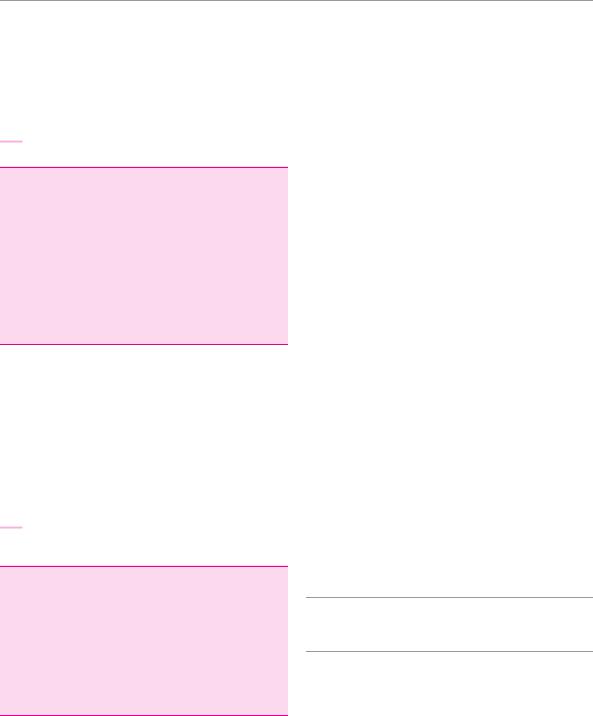

Course. The temporal course of multiple sclerosis (Fig. 8.1) can be characterized:

by the episodic appearance of new neurological deficits (relapsing type), which can then:

remit completely or almost completely,

leave residual deficits of greater or lesser severity, or

(rarely) fail to regress at all;

by episodic worsening at first, followed by steady progression (secondary progressive type);

by steady progression from the beginning (primary progressive type), as is most commonly seen in older patients with paraparesis; or

by steady progression with interspersed episodes of acute worsening (progressive relapsing type).

Clinical manifestations and neurological findings.

The general clinical features of MS are summarized in Table 8.1. The neurological deficits present in each individual patient depend on the number and location of the demyelinating foci. The following are among the more characteristic disease manifestations and physical findings:

Retrobulbar neuritis is usually unilateral. Over the course of a few days, the patient develops an impairment of color vision, followed by a marked impairment of visual acuity (finger counting is barely possible). Orbital pain is often present and the patient may see flashes of light on movement of the globe. These problems begin to improve in one or two weeks and usually resolve completely. The temporal side of the optic disc becomes pale three or four weeks after the onset of symptoms. Retrobulbar neuritis rarely affects both eyes, either at the same time or in rapid succession. Recurrences are rare. If retrobulbar neuritis is an isolated event in a patient otherwise free of neurological disease, the probability that other clinical signs of multiple sclerosis will appear in the future is roughly 50 %. This probability is greater if pathological changes are seen in the CSF (see below) or on an MRI scan (cf. Fig. 8.3, p. 159).

relapsing– remitting

secondary progressive

primary progressive

progressive relapsing

Fig. 8.1 The temporal course of multiple sclerosis: four major types.

Table 8.1 Clinical features of multiple sclerosis

Symptoms and |

Remarks |

signs |

|

|

|

Repeated attacks |

— separated in time after each attack |

|

— either complete recovery or residual |

|

deficit |

Diverse sites in |

— multiple, distinct sites may be involved |

CNS affected |

in a single attack |

|

— different sites are usually involved in |

|

different attacks |

|

— rarely, successive attacks may have simi- |

|

lar clinical manifestations (particularly |

|

when the lesions are in the spinal cord) |

Progressive neu- |

— cumulative progression, with worse re- |

rological impair- |

sidual deficits after each attack |

ment |

— steady progression independent of at- |

|

tacks (particularly in late-onset disease) |

|

|

clear ophthalmoplegia (p. 188), often without any subjective correlate. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia in a young patient is relatively specific for multiple sclerosis.

Lhermitte sign (positive neck-flexion sign). Active or passive forward flexion of the neck induces an “electric” paresthesia running down the spine and/or into the limbs.

!Retrobulbar neuritis, disturbances of ocular motility, sensory deficits, and Lhermitte sign are common early

findings in multiple sclerosis.

Pyramidal tract signs and exaggerated intrinsic muscle

Disturbances of ocular motility. Diplopia, particularly |

reflexes may be present early in the course of the dis- |

due to abducens palsy, is a common early symptom but |

ease. The abdominal cutaneous reflexes are absent. Later |

nearly always resolves spontaneously. Later, typical |

on, in almost all patients, spastic paraparesis or quadri- |

findings are nystagmus (often dissociated) and internu- |

paresis develops. |

ThiemeARgoOne ArgoOnebold

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

157

Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

8

158 8 Multiple Sclerosis and other Myelinopathies

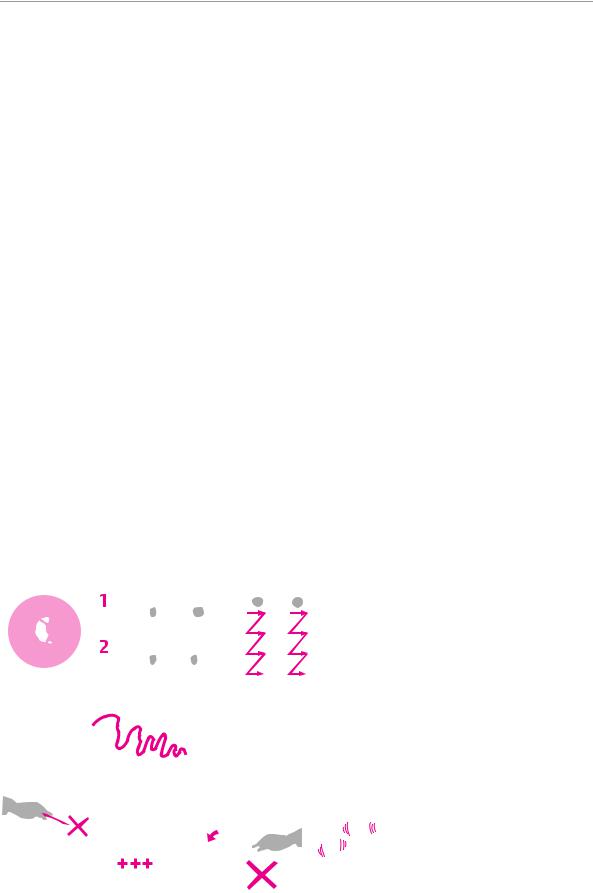

Cerebellar signs are practically always present in advanced MS, including impaired coordination, ataxia, and, frequently, a very characteristic intention tremor (Fig. 3.20 [p. 28], Fig. 8.2).

Gait impairment often becomes severe early in the course of the disease. Typically, the combination of spastic paraparesis and ataxia results in a spastic−ataxic, uneven, uncoordinated, and stiff gait (p. 14, Fig. 3.2).

Sensory deficits are found early in the course of the disease in about half of all patients. Vibration sense in the lower limbs is nearly always impaired. Pain is not uncommon; sometimes there is even a dissociated sensory deficit.

Bladder dysfunction is present in about three-quarters of all patients (generally in association with spasticity); disturbances of defecation are much rarer. Bladder dysfunction is sometimes an early manifestation of the disease. Urge incontinence is highly characteristic, i. e., a sudden, almost uncontrollable need to urinate, perhaps leading to “accidents” and bedwetting. Patients often do not mention bladder dysfunction until they are directly asked about it.

Ictal phenomena of various types are not uncommon. It is still debated whether MS causes epileptic seizures. About 1.5 % of persons with MS suffer from trigeminal neuralgia, which may alternate from one side to the other. Acute dizzy spells can occur, as can paroxysmal dystonia, dysarthria, or ataxia. The characteristic socalled tonic brainstem seizures consist of paroxysmal, often painful, tonic stiffness of the muscles on one side of the body. The lower limb is hyperextended, the upper limb flexed (Wernicke−Mann posture). The patient re-

mains fully conscious. Tonic brainstem seizures are often provoked by a change of position; they last less than one minute and are followed by a refractory period of a half hour or more in which no further seizures can occur. Tonic brainstem seizures and most other MS-as- sociated ictal phenomena respond to treatment with carbamazepine or other antiepileptic drugs.

Mental disturbances are not severe early in the course of the disease. Later on, however, many patients develop psycho-organic changes and psychoreactive and depressive disturbances. Psychosis is very rare.

The typical clinical findings in multiple sclerosis are shown schematically in Fig. 8.2.

Diagnostic evaluation. The typical physical findings

(see above) reveal the involvement of multiple areas of the nervous system by lesions separated in space and time. The following ancillary tests are also useful:

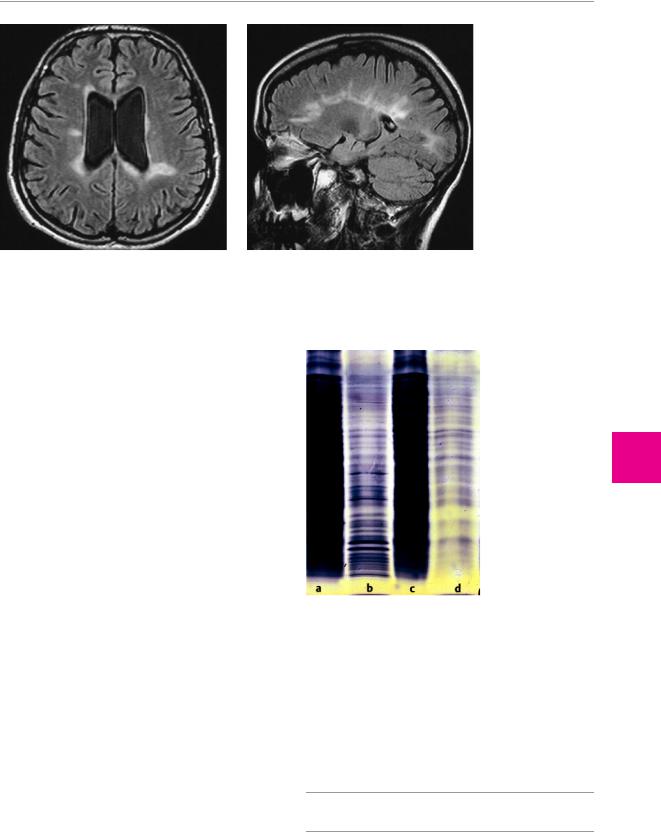

Neuroimaging studies, particularly MRI, typically reveal abnormal white matter signal in the periventricular regions and the corpus callosum. Active MS plaques take up contrast medium (Fig. 8.3).

Cerebrospinal fluid examination reveals a mild elevation of the total protein concentration, mild lymphocytic and plasma cell pleocytosis, and, in 90 % of patients, oligoclonal banding (demonstrable by isoelectric focusing, Fig. 8.4).

Electrophysiological testing: delayed latency of the visual evoked potentials is typical.

Treatment. Individual acute episodes (relapses) are treated with high-dose steroids, e. g., methylprednisolone 500 mg i. v. per day for five days, followed by oral prednisone, initially 100 mg per day and then in tapering doses, for two weeks. Patients with frequent re-

Fig. 8.2 Common physical findings in multiple sclerosis (diagram).

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Multiple Sclerosis

a |

b |

Fig. 8.3 MRI of the brain in multiple sclerosis. a Asymmetrically scattered foci of abnormal signal, affecting only the white matter, are seen in the periventricular regions and at the anterior and post-

lapses are treated over the long term with the immune modulator -interferon, at a dose of (for example) 8 × 106 IU s.c. q.i.d. for three or four days every week. This lowers the number of relapses per year by about 30 %. Copolymer-1, a synthetic mixture of amino acids, has a comparable effect when injected subcutaneously every day. -Interferon is also thought to be an effective treatment for the secondary progressive forms of MS. In general, these drugs can slow the progression of the disease, but they cannot stop it. Thus, general treatment measures remain very important: patient education, symptomatic treatments (antispasmodic drugs, treatment of bladder infections, etc.), psychological and rehabilitative treatment (especially physical therapy).

Differential diagnosis. Generally speaking, when a patient presents with an isolated neurological deficit that would be typical of MS, the differential diagnosis must include all other conditions that could produce that deficit. Even recurrent and relapsing neurological deficits referable to more than one part of the nervous system (the typical clinical picture of MS) do not by themselves establish the diagnosis. The most important elements of the differential diagnosis are listed in Table 8.2.

Prognosis. Patient survival 10 years after the onset of MS is nearly the same as that of a normal control population, and the total life span is reduced by no more than a few years. Advanced age at the onset of disease confers a worse prognosis, but only the disease takes a primary or secondary progressive course. Further unfavorable prognostic factors include cerebellar and brainstem signs, rapid initial progression, and a brief interval be-

erior ends of the lateral ventricles. There is mild internal hydrocephalus. b There are typical signal abnormalities in the corpus callosum, extending into the white matter of the hemispheres.

Fig. 8.4 Oligoclonal bands in the serum (a) and CSF (b) of a patient with multiple sclerosis; compare with the serum (c) and CSF (d) of a normal control subject.

tween the onset of disease and the first relapse. The patient’s condition five years after onset is closely correlated with their condition 10 and 15 years after onset, particularly with respect to cerebellar and pyramidal tract signs. About one-third of patients have no major disability 10 years after onset and a few percent still have none 25 years later.

! Multiple sclerosis sometimes takes a “benign” course.

159

Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

8

ThiemeARgoOne ArgoOnebold

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.