- •Overview

- •Preface

- •Translator’s Note

- •Contents

- •1. Fundamentals

- •Microscopic Anatomy of the Nervous System

- •Elements of Neurophysiology

- •Elements of Neurogenetics

- •General Genetics

- •Neurogenetics

- •Genetic Counseling

- •2. The Clinical Interview in Neurology

- •General Principles of History Taking

- •Special Aspects of History Taking

- •3. The Neurological Examination

- •Basic Principles of the Neurological Examination

- •Stance and Gait

- •Examination of the Head and Cranial Nerves

- •Head and Cervical Spine

- •Cranial Nerves

- •Examination of the Upper Limbs

- •Motor Function and Coordination

- •Muscle Tone and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Trunk

- •Examination of the Lower Limbs

- •Coordination and Strength

- •Reflexes

- •Sensation

- •Examination of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Neurologically Relevant Aspects of the General Physical Examination

- •Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Examination

- •Psychopathological Findings

- •Neuropsychological Examination

- •Special Considerations in the Neurological Examination of Infants and Young Children

- •Reflexes

- •4. Ancillary Tests in Neurology

- •Fundamentals

- •Imaging Studies

- •Conventional Skeletal Radiographs

- •Computed Tomography (CT)

- •Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- •Angiography with Radiological Contrast Media

- •Myelography and Radiculography

- •Electrophysiological Studies

- •Fundamentals

- •Electroencephalography (EEG)

- •Evoked potentials

- •Electromyography

- •Electroneurography

- •Other Electrophysiological Studies

- •Ultrasonography

- •Other Ancillary Studies

- •Cerebrospinal Fluid Studies

- •Tissue Biopsies

- •Perimetry

- •5. Topical Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Neurological Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Muscle Weakness and Other Motor Disturbances

- •Sensory Disturbances

- •Anatomical Substrate of Sensation

- •Disturbances of Consciousness

- •Dysfunction of Specific Areas of the Brain

- •Thalamic Syndromes

- •Brainstem Syndromes

- •Cerebellar Syndromes

- •6. Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Congenital and Perinatally Acquired Diseases of the Brain

- •Fundamentals

- •Special Clinical Forms

- •Traumatic Brain injury

- •Fundamentals

- •Traumatic Hematomas

- •Complications of Traumatic Brain Injury

- •Intracranial Pressure and Brain Tumors

- •Intracranial Pressure

- •Brain Tumors

- •Cerebral Ischemia

- •Nontraumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage

- •Infectious Diseases of the Brain and Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Meninges

- •Infections Mainly Involving the Brain

- •Intracranial Abscesses

- •Congenital Metabolic Disorders

- •Acquired Metabolic Disorders

- •Diseases of the Basal Ganglia

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases Causing Hyperkinesia

- •Other Types of Involuntary Movement

- •Cerebellar Diseases

- •Dementing Diseases

- •The Dementia Syndrome

- •Vascular Dementia

- •7. Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Anatomical Fundamentals

- •The Main Spinal Cord Syndromes and Their Anatomical Localization

- •Spinal Cord Trauma

- •Spinal Cord Compression

- •Spinal Cord Tumors

- •Myelopathy Due to Cervical Spondylosis

- •Circulatory Disorders of the Spinal Cord

- •Blood Supply of the Spinal Cord

- •Arterial Hypoperfusion

- •Impaired Venous Drainage

- •Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases of the Spinal Cord

- •Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia

- •Diseases Mainly Affecting the Long Tracts of the Spinal Cord

- •Diseases of the Anterior Horns

- •8. Multiple Sclerosis and Other Myelinopathies

- •Fundamentals

- •Myelin

- •Multiple Sclerosis

- •Other Demyelinating Diseases of Unknown Pathogenesis

- •9. Epilepsy and Its Differential Diagnosis

- •Types of Epilepsy

- •Classification of the Epilepsies

- •Generalized Seizures

- •Partial (Focal) Seizures

- •Status Epilepticus

- •Episodic Neurological Disturbances of Nonepileptic Origin

- •Episodic Disturbances with Transient Loss of Consciousness and Falling

- •Episodic Loss of Consciousness without Falling

- •Episodic Movement Disorders without Loss of Consciousness

- •10. Polyradiculopathy and Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •Polyradiculitis

- •Cranial Polyradiculitis

- •Polyradiculitis of the Cauda Equina

- •Polyneuropathy

- •Fundamentals

- •11. Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Disturbances of Smell (Olfactory Nerve)

- •Neurological Disturbances of Vision (Optic Nerve)

- •Visual Field Defects

- •Impairment of Visual Acuity

- •Pathological Findings of the Optic Disc

- •Disturbances of Ocular and Pupillary Motility

- •Fundamentals of Eye Movements

- •Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Supranuclear Oculomotor Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Nerves to the Eye Muscles and Their Brainstem Nuclei

- •Ptosis

- •Pupillary Disturbances

- •Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve

- •Lesions of the Facial Nerve

- •Disturbances of Hearing and Balance; Vertigo

- •Neurological Disturbances of Hearing

- •Disequilibrium and Vertigo

- •The Lower Cranial Nerves

- •Accessory Nerve Palsy

- •Hypoglossal Nerve Palsy

- •Multiple Cranial Nerve Deficits

- •12. Diseases of the Spinal Nerve Roots and Peripheral Nerves

- •Fundamentals

- •Spinal Radicular Syndromes

- •Peripheral Nerve Lesions

- •Fundamentals

- •Diseases of the Brachial Plexus

- •Diseases of the Nerves of the Trunk

- •13. Painful Syndromes

- •Fundamentals

- •Painful Syndromes of the Head And Neck

- •IHS Classification of Headache

- •Approach to the Patient with Headache

- •Migraine

- •Cluster Headache

- •Tension-type Headache

- •Rare Varieties of Primary headache

- •Symptomatic Headache

- •Painful Syndromes of the Face

- •Dangerous Types of Headache

- •“Genuine” Neuralgias in the Face

- •Painful Shoulder−Arm Syndromes (SAS)

- •Neurogenic Arm Pain

- •Vasogenic Arm Pain

- •“Arm Pain of Overuse”

- •Other Types of Arm Pain

- •Pain in the Trunk and Back

- •Thoracic and Abdominal Wall Pain

- •Back Pain

- •Groin Pain

- •Leg Pain

- •Pseudoradicular Pain

- •14. Diseases of Muscle (Myopathies)

- •Structure and Function of Muscle

- •General Symptomatology, Evaluation, and Classification of Muscle Diseases

- •Muscular Dystrophies

- •Autosomal Muscular Dystrophies

- •Myotonic Syndromes and Periodic Paralysis Syndromes

- •Rarer Types of Muscular Dystrophy

- •Diseases Mainly Causing Myotonia

- •Metabolic Myopathies

- •Acute Rhabdomyolysis

- •Mitochondrial Encephalomyopathies

- •Myositis

- •Other Diseases Affecting Muscle

- •Myopathies Due to Systemic Disease

- •Congenital Myopathies

- •Disturbances of Neuromuscular Transmission−Myasthenic Syndromes

- •15. Diseases of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Anatomy

- •Normal and Pathological Function of the Autonomic Nervous System

- •Sweating

- •Bladder, Bowel, and Sexual Function

- •Generalized Autonomic Dysfunction

- •Index

Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve 195

Lesions of the Trigeminal Nerve

The trigeminal n. is responsible for the somatosensory innervation of the skin of the face and forehead and of many of the mucous membranes of the face and head. It also carries motor fibers innervating the muscles of mastication. Lesions of this nerve thus produce sensory deficits and paralysis of the muscles of mastication.

The anatomical course and distribution of the trigeminal n. are shown in Fig. 3.10, p. 23 and the technique of clinical examination is presented on p. 22.

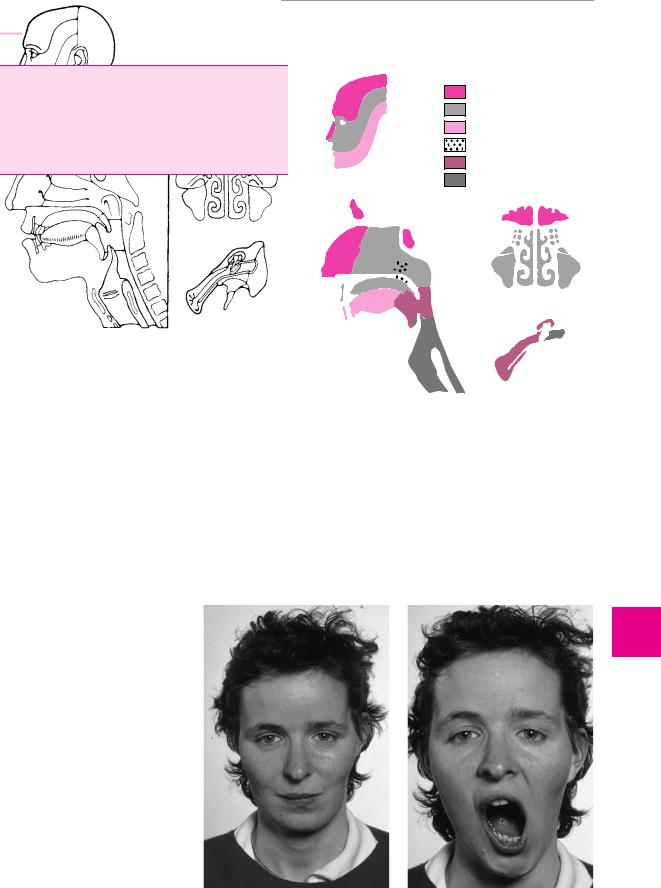

Clinical manifestations. Trigeminal lesions produce sensory deficits in the face and head. The somatosensory distribution of the three branches of the trigeminal n. are shown in Fig. 11.13. A lesion of the motor portion of the third branch causes paralysis of the muscles of mastication. The examiner can usually easily feel the diminished contraction of the masseter m. on one side. When the mouth is opened, the jaw deviates toward the paralyzed side because of weakness of the pterygoid mm. (Fig. 11.14).

Causes. Nuclear lesions of the trigeminal n. are located in the pons or medulla and are usually due to vascular processes, encephalitis, a focus of multiple sclerosis, or a space-occupying lesion (glioma, syringobulbia). The nerve can also be affected in its peripheral course by mass lesions, toxic influences, or mechanical (iatrogenic) factors. The trigeminal n. can also be affected as a component of cranial polyradiculitis. Occasionally, no clear cause can be found (idiopathic trigeminal neuropathy, which is usually unilateral). Trigeminal neuralgia is discussed below on p. 253.

ophthalmic n. (V1) maxillary n. (V2) mandibular n. (V3) nervus intermedius (VII)

glossopharyngeal n. (IX)

vagus n. (X)

Fig. 11.13 Sensory innervation of the face and the mucous membranes of the head.

Fig. 11.14 Lesion of the motor portion of the left trigeminal nerve. a

Atrophy of the left temporalis and masseter muscles. b Deviation of the jaw to the left on opening.

a |

b |

Thieme Argo OneArgo bold

ArgoOneBold

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme

All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

11

196 11 Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

Lesions of the Facial Nerve

This mainly motor cranial nerve innervates the muscles of facial expression. It also provides taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and innervates the lacrimal and salivatory glands. Lesions of the facial n. usually lie in the peripheral nerve trunk and are clinically evident mainly as facial palsy. Peripheral facial nerve palsy often arises without any apparent cause (i. e., it is often cryptogenic). It must always be carefully differentiated from symptomatic weakness of the facial musculature of central or peripheral origin.

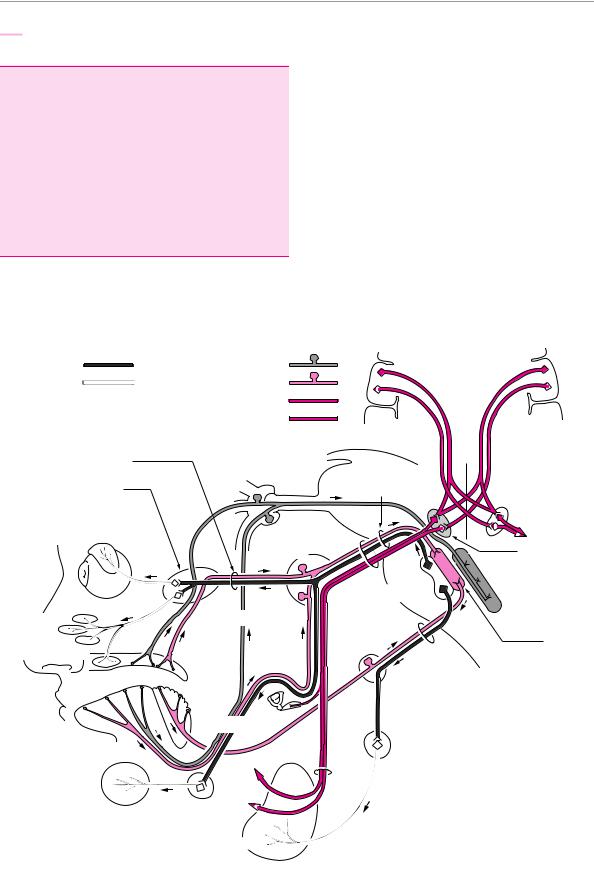

The anatomical course of the seventh cranial nerve is depicted in Fig. 11.15.

Topical classification. The clinical picture of a (complete) facial nerve palsy depends on the site of the lesion:

Lesions distal to the sternomastoid foramen typically cause a purely motor paralysis of all of the muscles of facial expression on one half of the face. The eye cannot be closed (lagophthalmos) and the forehead cannot be wrinkled. No other deficit is present.

Lesions of the facial n. in the petrous portion of the temporal bone or in the facial (Fallopian) canal (the most common site) cause disturbances of lacrimation and salivation, impairment of taste, and/or hyperacusis in addition to the motor weakness of the face. All of these manifestations occur to varying extents depending on the precise location of the lesion.

Neural pathways of: lacrimation and salivation

preganglionic |

mucosal sensation |

|

|

postganglionic |

taste |

|

|

* chorda tympani |

cranial part |

|

|

motor |

|

|

|

** stapedius m. |

caudal part |

|

|

|

|

|

|

greater petrosal n. |

semilunar |

|

|

|

ganglion |

nervus |

|

pterygopalatine |

V |

intermedius |

|

ganglion |

|

|

|

lacrimal |

|

|

|

gland |

geniculate |

VII |

|

|

facial nucleus |

||

|

ganglion |

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

salivatory |

nucleus of |

|

|

the spinal |

|

|

|

nucleus |

tract of the |

|

mandibular n. |

|

trigeminal n. |

|

|

|

|

nasal and |

|

IX |

solitary |

palatal glands |

|

|

|

palate |

|

nucleus |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

* |

superior/ |

|

tongue |

|

|

|

|

inferior |

|

|

|

|

ganglion |

|

lingual n. |

** |

|

|

|

otic |

|

ganglion |

sublingual and

submandibular

glands

submandibular gland

parotid gland

Fig. 11.15 Anatomy of the facial n. Note the bilateral central innervation of the cranial portion of the facial nerve nucleus. The caudal portion is only innervated by the contralateral hemisphere.

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

Lesions of the Facial Nerve

Lesions of the facial nerve nucleus or of its nerve fascicle within the brainstem are rarer and are mainly evident as a motor deficit including lagophthalmos and an inability to wrinkle the forehead. Lacrimation, salivation, and taste are normal, because the parasympathetic and gustatory fibers of the facial n. are derived from other cranial nerve nuclei in the brainstem.

Lesions above the facial nerve nucleus (= central facial palsy). The typical predominant finding in such cases is perioral weakness. The eye can still be closed on the affected side and the forehead can be symmetrically wrinkled.

Etiological classification. Cryptogenic facial palsy is the most common type and must be distinguished from other, symptomatic varieties. Its cause is unknown and is currently thought to be either a viral infection (e. g., by a herpesvirus) or a parainfectious process (see below). In symptomatic forms, a concrete cause for the facial palsy can be found: a basilar skull fracture, for example, can damage the facial n. Transverse fractures of the petrous bone cause immediate and often irreversible facial palsy. Longitudinal fractures frequently give rise to facial palsy only after a delay, usually because of a slowly expanding hematoma in the wall of the facial canal; the prognosis in such patients is better than in transverse fractures. Middle ear processes (cholesteatoma) can cause facial nerve palsy, as can skull base tumors and viral infections, particularly herpes zoster oticus. Borreliosis (Lyme disease) can affect the facial n. and produce a facial palsy. Bilateral facial palsy can be seen in (cranial) polyradiculitis. A nuclear facial nerve palsy results from infarction affecting the facial nerve nucleus in the pons, or from a brainstem glioma.

The most common type of peripheral facial palsy—the cryptogenic type—will now be described in detail.

Cryptogenic Peripheral Facial Nerve Palsy

Epidemiology. This condition (“Bell palsy”) accounts for three-quarters of all cases of facial palsy and has an annual incidence of ca. 25 per 100 000 individuals.

Etiology. The cause is unknown, but it is probably a viral infection. Swelling of the facial nerve trunk in the narrow confines of the facial canal leads to local compressive ischemia, which, in turn, leads to further swelling (a vicious circle). The result is a local interruption of the blood supply to the facial n. through the vasa nervorum and thus an extension of the ischemic injury, often leading to total axonotmesis.

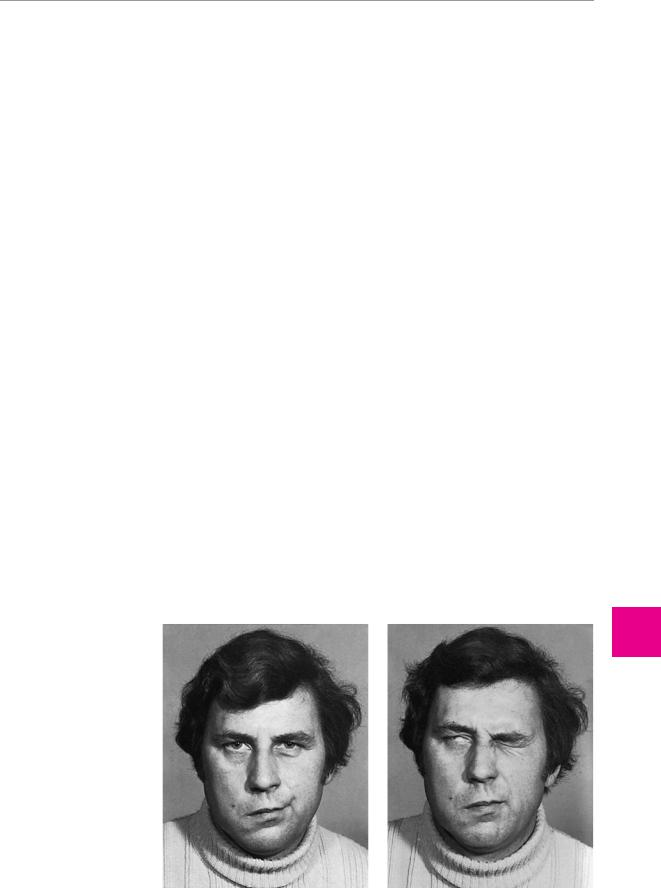

Clinical manifestations. The most prominent finding is weakness of the muscles of facial expression, which can be of variable extent but is often complete, as depicted in Fig. 11.16. There is also an impairment of taste on the anterior two-thirds of the tongue on the affected side (for the technique of examination, cf. p. 22). “Bitter” tastes can usually still be perceived, because the receptors for this modality lie in the mucosa of the posterior third of the tongue, which is innervated by the glossopharyngeal n. Lacrimation and salivation are also ipsilaterally impaired. Dysacusis or hyperacusis, due to denervation of the stapedius m., is hardly ever clinically evident.

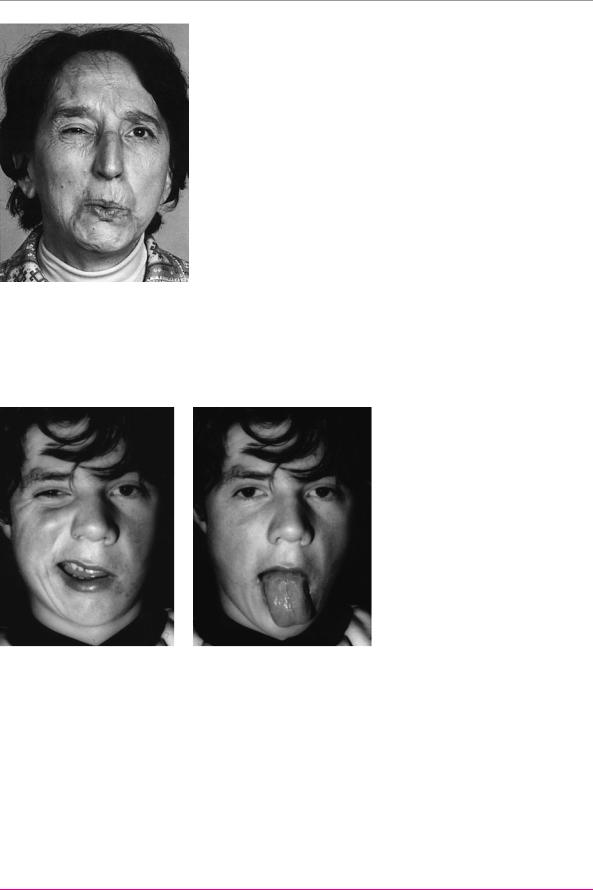

Prognosis. The prognosis is generally favorable: in 80 % of patients, the facial weakness resolves completely in four to six weeks. The remaining patients are those whose facial musculature has been completely denervated. For them, the recovery can take much longer (up to six months). Residual manifestations often include partial facial weakness or pathological accessory movements due to misdirection of regenerating axons. In cases of the latter type, active contraction of one part of the face is accompanied by simultaneous, involuntary contraction of another: thus, the patient’s ipsilateral eye may close involuntarily when he or she whistles (synkinesia, Fig. 11.17).

Fig. 11.16 Complete right peripheral facial nerve palsy

(cryptogenic type). a At rest, the right corner of the mouth and the right cheek hang limply downward. b The patient cannot close the eye on the side of the weakness (right side). This is called lagophthalmos. The eye turns upward, and part of it remains visible (Bell phenomenon).

a

Thieme Argo OneArgo bold

ArgoOneBold

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.

197

Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

11

b

198 11 Diseases of the Cranial Nerves

Fig. 11.17 Mass innervation of the face after right peripheral facial nerve palsy. Because of faulty redirection of regenerating motor axons to their muscular targets, the active contraction of a muscle group in the face can be accompanied by involuntary contraction of other muscle groups. In the patient shown, whistling is accompanied by involuntary eye closure. (From: Mumenthaler, M.:

Didaktischer Atlas der klinischen Neurologie. 2nd edn, Springer, Heidelberg 1986)

Differential diagnosis. Facial weakness of central origin must be distinguished from peripheral facial nerve palsy. In central weakness, the lesion lies above the level of the facial nerve nucleus, i. e., in the portion of the motor cortex subserving facial movements, or along the course of the corticobulbar efferent fibers. With meticulous clinical examination, one can always distinguish central from peripheral facial weakness; the criteria for making the distinction are summarized in Table 11.7. The most important one is the lesser involvement of the forehead and periocular musculature, compared with the remainder of the facial muscles, in central facial palsy.

The explanation is that the neurons in the superior portion of the facial nerve nucleus in the pons receive impulses from both cerebral hemispheres; therefore, a unilateral lesion of the motor cortex or corticobulbar tract can usually be compensated for by the corresponding, intact pathway on the opposite side (cf. Fig. 11.15). The caudal portion of the facial nerve nucleus, on the other hand, is “controlled” only by the contralateral hemisphere.

In addition, central facial palsy is often accompanied by weakness elsewhere in the body in areas not inner-

Fig. 11.18 Left central facial palsy. a Impaired innervation of the lower portion of the face is evident when the patient tries to show his teeth. b As part of the central hemiparesis, the motor innervation of the left side of the tongue is also impaired, and the tongue therefore deviates to the left on protrusion.

a |

b |

|

Table 11.7 Differentiation of central and peripheral facial palsy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Central facial palsy |

Peripheral facial palsy |

|

|

|

History |

Usually seen in elderly persons as a sudden, acute |

|

event; usually accompanied by hemiparesis mainly |

|

affecting the upper limb |

Facial appear- |

Usually normal |

ance at rest |

|

May occur at any age; often accompanied by retroauricular pain; weakness develops over the course of one or two days, rather than suddenly

Often normal; blinking may be less frequent; the affected side of the face is flaccid in longstanding, complete peripheral facial palsy

Examination of |

The globe is always completely covered when the |

facial muscula- |

patient closes the eyes; the frontal branch is always |

ture |

much less affected |

If the palsy is complete, the patient can never completely close the affected eye (though this is still possible in partial lesions of CN VII); the frontal branch is affected to the same extent as the rest of the nerve (Fig. 11.16)

Additional |

There may be accompanying, ipsilateral weakness |

findings |

of the tongue, or central hemiparesis of the ipsila- |

|

teral limbs |

In the cryptogenic form, the sense of taste is lost on the ipsilateral side of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue; diminished lacrimation and salivation; electromyography reveals denervation

Mumenthaler / Mattle, Fundamentals of Neurology © 2006 Thieme All rights reserved. Usage subject to terms and conditions of license.