- •Unit 5 Art Part 1 Evolution Lead-in

- •Impressionism

- •Reading

- •Paul Gauguin

- •1879-81: The First Exhibitions

- •1882-85: Rouen and Copenhagen

- •1887: The first trip to Martinique

- •1888: Pont-Aven

- •The Flowers of France

- •Mataïea

- •What! Are you Jealous?

- •Exercises

- •Talking and Writing

- •Role-play

- •Additional Vocabulary Exercises

- •Translation Practice

- •Unit 5 Art Part 2 Modern Art Lead-in

- •Reading

- •It's rude, witty, but is it art?

- •Exercises

- •Voluble, inscrutable, poised, baffle, sublime, lame, extravaganza, juxtapose, alter-ego, render

- •Role-play

- •Tate modern

- •Talks & Tours

- •Daily Guided Tours

- •Writing and Vocabulary Work

- •Translation Exercises

- •Unit 5 Art Part 3 Heritage Lead-in

- •Reading

- •Exercises

- •Talking and Writing

- •Role-play

- •Additional Language Exercises

- •Unit 5 Art Part 4 Ukrainian Art Lead-in

- •Reading

- •Modernization of Ukrainian Culture

- •Executive Summary

- •Exercises

- •Talking and Writing

- •Role-play

- •Additional Language Exercises

- •State museum of ukrainian decorative art

Reading

Below is a newspaper article from the Observer. Read it, study its language for further exercises and discussions.

It's rude, witty, but is it art?

Observer, November 26, 2000

They are in their twenties, probably lovers, certainly unmarried. He wears a thin grey jersey and leather trousers, with carefully maintained stubble and wraparound shades, despite the dim light. She is Japanese, dressed in a bright plastic jacket, child colours, unsmiling. They are standing among a scattering of domestic electric detritus on a polished floor. They exchange a look, impossible to interpret. The man mutters and they move on, glancing at a book he holds.

N ext

will be a large blurred image. It promises to be 'oddly troubling'.

After that, a sagging fabric thing, in muddy grey, described in the

booklet as 'profoundly disturbing'. What are they thinking? What need

has brought them here? Are they oddly troubled, profoundly disturbed?

Would they like to be?

ext

will be a large blurred image. It promises to be 'oddly troubling'.

After that, a sagging fabric thing, in muddy grey, described in the

booklet as 'profoundly disturbing'. What are they thinking? What need

has brought them here? Are they oddly troubled, profoundly disturbed?

Would they like to be?

A

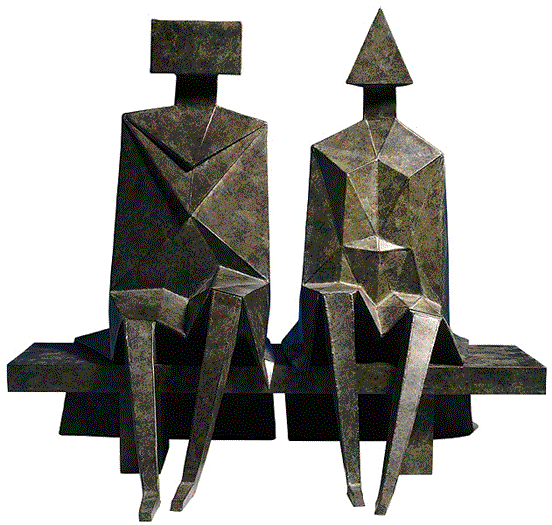

Lynn

Chadwick. "Sitting Couple"

Because contemporary art has been such a fashionable success, attracting huge numbers to the big shows, whose sense of élite art is fed by the tabloid papers, we have become stuck in an absurd 'modern art - for or against it?' debate. You are part of the tribe, or you are in the mocking crowd outside the temple.

It was not always this way. Religious art, obviously, told stories through images that had been drummed into its users by priests and parents from an early age. These images might be traditional or surprisingly new, but their story was common and well-known. Paintings of classical myth were for the select, though everyone educated knew their Dianas and Actaeons. Works of later secular art, showing the faces of rulers, or battles by land and sea, expensive clothes and flowers, houses and eventually landscapes, were immediately comprehensible renderings of the social context. If you had never seen a Vermeer or heard of Constable, and you stumbled into a gallery and saw one, you would not be baffled.

Meanwhile, because 'art' was the application of a limited number of motor skills inside a tradition – composition, line, muscle, tone, palette, balance - and the aesthetic arguments around them, it was relatively easy to place art in a hierarchy from sublime to awful. You can draw or you can't. You have colour sense or not. You follow lamely in composition or you have a new idea. You copy or reinterpret.

Then we have cubism and abstract art and the division begins. On the one side, the great all-pervasive sea of images produced by mass urban culture, the Hollywood films, postcards, advertising hoardings, glossy magazines, TV shows, rock extravaganzas, 'the stuff that surrounds you' and which we consume every day. On the other, trying desperately to dissociate oneself from that, 'modern art' - alternative images, paint without a story, deliberately complicated and confusing juxtapositions, the ironies and absences, the intellectual refuge.

As artists look for other materials, from lumps of graphite to film, old clothes to burned-out cars, stage props to firebricks, Polaroid snaps and rubbish heaps, - the difficulty of comparing, separating sheep from goats, grows ever harder. In the absence of commonly understood stories, religious or historical, art has to be explained with words. This, however, requires concentration and intellectual determination. So the tribe, the art élite, the culture caste proper, was born.

To understand, then enjoy contemporary art becomes a way of defining yourself as better than the rest. The harder the art, the greater the credit. This doesn't start with Whistler or even Picasso. It starts with Marcel Duchamp, the great granddaddy of conceptual art, user of found images, signed urinals, playful alter-egos, sexual shock, vastly complex mental systems. Duchamp is the high priest. Without him many following works like Damien Hirst's, are unthinkable.

Of course, there are the easily and immediately enjoyed, more traditional artists, but they are looked down on by the true tribe.

Does it matter? Should we care that there is an urban art caste while nine-tenths of the public are baffled and ignorant? Hasn't art always been exclusive? Isn't that why we used to talk of 'fine' art?

It matters, because most people are still missing out on it. The self-selected art élite are also part of the problem. A lot of what is on display does show the limitations of the art tribe. The fact that contemporary art is particularly popular among highly educated, relatively youthful urban strata, has tilted it towards coolness, chic, multiple ironies, towards glossy, machined objects that mirror the aesthetics of the city.

The reassuring point is that most of the contemporary art around in 2000 is not immediately difficult or chilly. The artists themselves are breaking down the barriers. Susan Hiller's work 'Witness', in which hundreds of earphones dangle from a darkened room, while recorded witness statements from people across the world who have claimed to see UFOs or aliens whisper in scores of languages around you, like fingers brushing your ears as you walk through - well, just amazing, simple and beautiful. That was in 'Intelligence' at Tate Britain. And there are literary hundreds of other examples.

The truth is that contemporary art is not haunted by Duchamp or any other twentieth century thinker, but by more romping, passionate ghosts and it would be a terrible thing if those kept people away. I mean that couple I started with - the cool ones. It is time to elbow them aside and fill up the galleries with the rest of us.