economics_of_money_banking__financial_markets

.pdf

|

C H A P T E R 2 3 The Keynesian Framework and the ISLM Model 551 |

|

Study Guide |

To test your understanding of the Keynesian analysis of how aggregate output changes |

|

|

||

|

in response to changes in the factors described, see if you can use Keynesian cross dia- |

|

|

grams to illustrate what happens to aggregate output when each variable decreases |

|

|

rather than increases. Also, be sure to do the problems at the end of the chapter that |

|

|

ask you to predict what will happen to aggregate output when certain economic vari- |

|

|

ables change. |

|

|

|

|

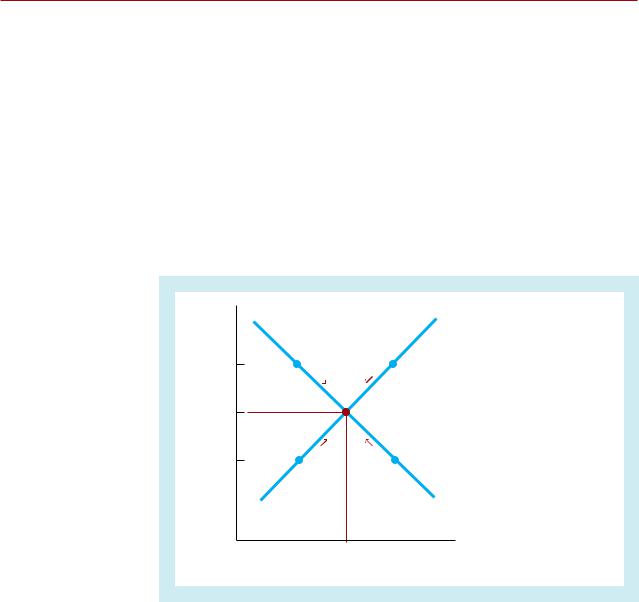

The ISLM Model

So far, our analysis has excluded monetary policy. We now include money and interest rates in the Keynesian framework in order to develop the more intricate ISL M model of how aggregate output is determined, in which monetary policy plays an important role. Why another complex model? The ISL M model is more versatile and allows us to understand economic phenomena that cannot be analyzed with the simpler Keynesian cross framework used earlier. The ISL M model will help you understand how monetary policy affects economic activity and interacts with fiscal policy (changes in government spending and taxes) to produce a certain level of aggregate output; how the level of interest rates is affected by changes in investment spending as well as by changes in monetary and fiscal policy; how best to conduct monetary policy; and how the ISL M model generates the aggregate demand curve, an essential building block for the aggregate supply and demand analysis used in Chapter 25 and thereafter.

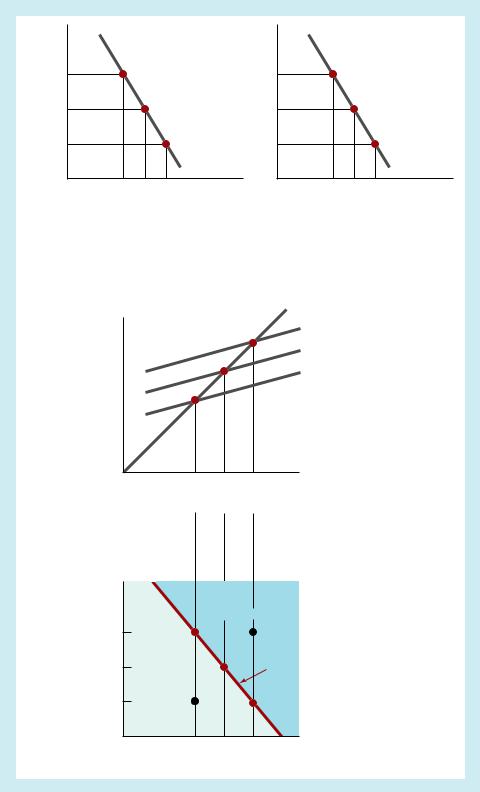

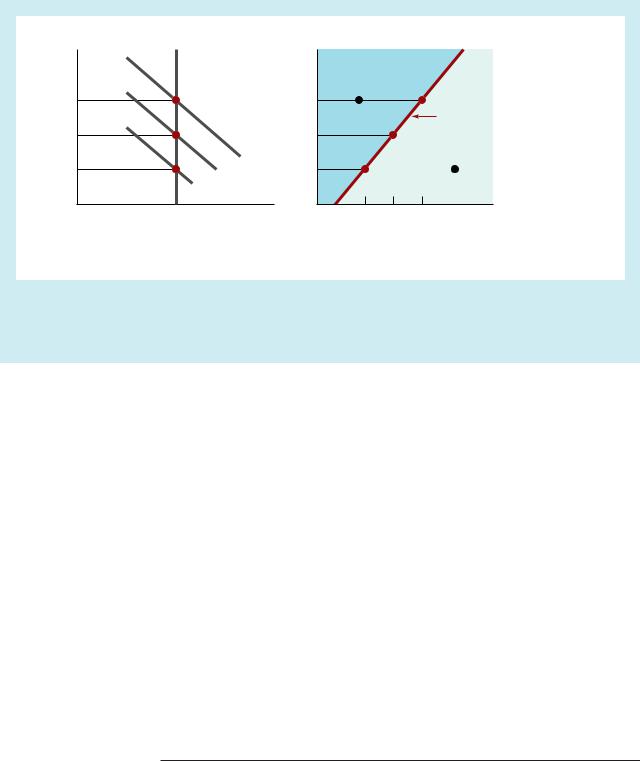

Like our simplified Keynesian model, the full Keynesian ISL M model examines an equilibrium in which aggregate output produced equals aggregate demand, and since it assumes a fixed price level, real and nominal quantities are the same. The first step in constructing the ISL M model is to examine the effect of interest rates on planned investment spending and hence on aggregate demand. Next we use a Keynesian cross diagram to see how the interest rate affects the equilibrium level of aggregate output. The resulting relationship between equilibrium aggregate output and the interest rate is known as the IS curve.

Just as a demand curve alone cannot tell us the quantity of goods sold in a market, the IS curve by itself cannot tell us what the level of aggregate output will be because the interest rate is still unknown. We need another relationship, called the LM curve, which describes the combinations of interest rates and aggregate output for which the quantity of money demanded equals the quantity of money supplied.

which can be solved for Y. The resulting equation:

1

Y A 1 mpc

is the same equation that links autonomous spending and aggregate output in the text (Equation 5), but it now allows for additional components of autonomous spending in A. We see that any increase in autonomous expenditure leads to a multiple increase in output. Thus any component of autonomous spending that enters A with a positive sign (a, I, G, and N X ) will have a positive relationship with output, and any component with a negative sign ( mpc T ) will have a negative relationship with output. This algebraic analysis also shows us that any rise in a component of A that is offset by a movement in another component of A, leaving A unchanged, will also leave output unchanged.