- •От автора

- •Glimpses of British History

- •Early Britain

- •The House of Normandy

- •Medieval England

- •Tudor England

- •The Stuarts

- •Georgian Britain

- •Victorian Britain

- •Edwardian Britain

- •Britain and the two World Wars

- •Britain after World War II

- •Modern Britain

- •Modern British Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •The House of Lords

- •The House of Commons

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses and British Heritage

- •Glossary

- •British History

- •Modern Britain

- •The Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •Elections

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses

- •Architecture

- •Key to some phonetic symbols:

- •Bibliography

- •Dictionaries Used

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Victorian Britain

On 20 June 1837 at about two o’clock in the morning William IV died. Four hours later his eighteen-year-old niece Victoria was woken up in Kensington Palace and, still in her dressinggown and slippers, learnt that she had become queen. Thus began a reign that was to be the longest in British history, spanning the greater part of the 19th century and ending in the 20th (1901); and Victoria was to give her name to a glorious age which still makes an indelible impression upon the imagination.

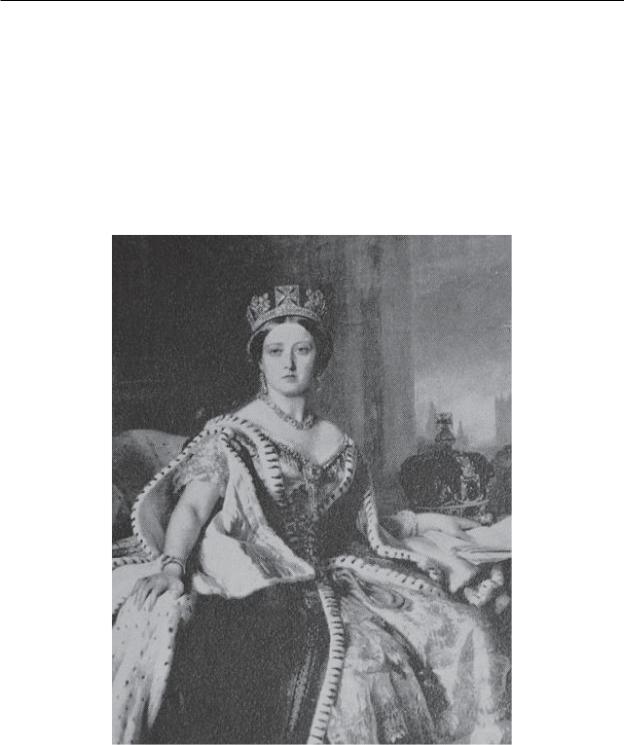

Victoria

Victoria started her reign as a wilful and passionate young woman, who was also ill-educated and inexperienced. Very soon she was to discover that the political role of the Crown had been further reduced in the years preceding her accession. Although all acts of government continued to be carried out in the name of the sovereign and the monarch still chose the Prime Minister and asked him to form a ministry, the choice was narrowed to someone who had the general confidence of Parliament and especially the House of Commons. Prime Ministers, even if supported by the monarch, could no longer be sustained in office if they failed to win a Commons majority. In 1834 William IV had granted the Prime Minister’s request for dissolution. Henceforth such a request by a Prime Minister was never again to be refused.

68

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

At the beginning of Victoria’s reign her headstrong temperament, her susceptibility to the undemocratic ideas of Continental royalty and open preference for Lord Melbourne and the Whigs became a real danger to the monarchy. Fortunately, she also had a sense of duty, earnestness, a determination ‘to be good’ (at the age of 11 she made her famous promise ‘I will be good’ which became, as it were, the guiding thread in her life) and the will to improve.

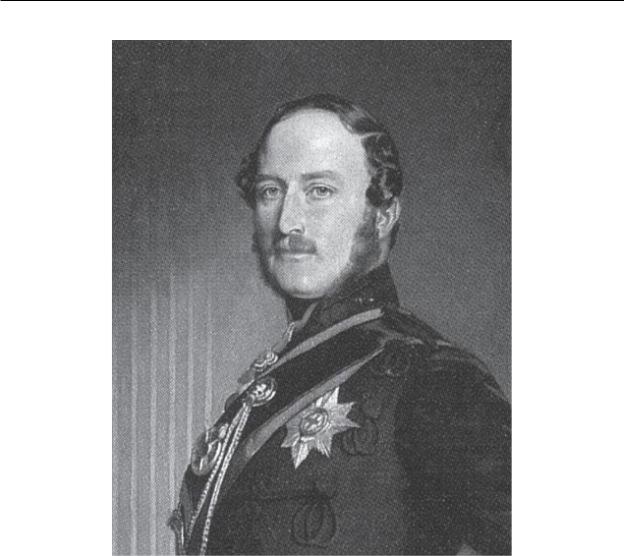

When Victoria came to the throne Melbourne had been Prime Minister for two years and his majority in the Commons, though fragile, was confirmed by the election required by the death of William IV. Melbourne gave a great deal of time and attention to the political education and advising of the young queen, becoming for her a sort of father figure, and she came to rely heavily on him. In 1839 Melbourne was defeated in the Commons, which led to the resignation of the whole Cabinet. Yet, when the Tory leader Robert Peel sought to put together a new ministry and told the queen to dismiss her Whig Ladies of the Bedchamber, who, he feared, might have undue influence on her, Victoria bluntly refused, unwilling to lose both Melbourne and her social companions at court. Melbourne was asked to remain in office; he accepted and was able to maintain a tenuous majority until 1841. In 1840 he helped arrange the marriage of Victoria to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg- Gotha. Albert became a knowledgeable and hard-working Prince Consort to whom Victoria was deeply devoted, but whom the nation never understood or appreciated during his lifetime. He developed a new role for the Crown as a unifying force rising above political parties. The monarch’s role in home affairs was to be limited to advice and warning, however strong personal preferences might be. The slow recovery of respect for the Crown dated from the queen’s marriage. The Court changed greatly compared with the previous two reigns. The royal family, guided by a punctilious ideal of personal duty, became a model for private morality, decency, economy and domestic virtues. Interest in the arts and sciences, in learning and educating both the general masses and their own children, in national achievements and good works was now the focus of the royal attention. Belief in and striving after improvement were to become the essence of the whole Victorian age. Soon the Court found its perfect servant in Sir Robert Peel.

69

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Prince Albert

The mid-Victorian years (1841–1865) were a time of remarkable prosperity. Thriving on free trade and not yet encountering any foreign competition, Britain had reason to enjoy its industrial leadership. The achievements of industry and the country’s unchallenged supremacy in world leadership gave rise to a spirit of confidence in the present and faith in the idea of progress.

The election of 1841 gave the Tories a clear majority, and by this time both the queen and Parliament had recognized that the monarch must choose a Prime Minister who could command a majority in the House of Commons. Reluctant as Victoria was to lose Melbourne, she had to ask Robert Peel to form a government. In 1841 Peel was already an experienced politician, who had previously reformed criminal law and established the metropolitan police force in his capacity as Home Secretary. Now he and his party accepted the idea of gradual reform, free trade, and an industrial, rather than an agrarian society as the basis of Britain’s prospering economy. However, as soon as Peel took office he faced the agitation of the Chartists and the Anti-Corn Law League.

Chartism had originated in the late 1830s. This political movement called for universal male suffrage, the abolition of the property qualification for MPs, annual general elections, electoral districts of equal size, the payment of MPs and a secret ballot. Actually, five out of the six demands were granted later, by 1918. But in the late 1830s and early 1840s they were revolutionary. The main form of protest was a charter, or petition presented to Parliament. Altogether there were three major petitions. The campaign, demonstrations and strikes achieved nothing in the end, though the movement lingered until 1848, and was finally made redundant by Victorian prosperity.

70

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

A more serious challenge to Peel came in the form of the Anti-Corn League. The League had been organized in 1839 in Manchester with the financial backing and political support of the manufacturers. It wished to rouse public opinion against the Corn Law which protected agricultural interests by keeping high the price of food and forbidding the import of lower-priced corn. The propaganda of the League, economic depression and bad weather conditions combined to convert the public and Peel to free trade. In the budget of 1842 he introduced an income tax of seven pence in the pound sterling on all annual incomes over Ј150. Never before had such a form of taxation been levied in time of peace. Peel then proceeded to reduce the tariffs on imported and exported goods. By 1846 duties on almost all raw materials had been removed, and the tariffs on other imports radically cut. In this situation ending agricultural protection by repealing the Corn Law made economic sense and was a step forward, but when Peel finally brought himself to do it, the decision ruined him politically and divided the Tory party. It brought forward Benjamin Disraeli as the leader of the country squires and permitted two decades of Whig-Liberal dominance. Free trade soon became a basic principle of Victorian England.

After Peel’s resignation in 1846 there was a shifting kaleidoscope of ministries for over a decade, in which party labels didn’t mean much. The Tory party was split into a protectionist wing headed by Disraeli and a smaller, but influential, faction known as the Peelites. Though the Whigs were a dominant party, they were by no means united. The more conservative ones headed by Russell and Palmerston saw little need for further reform, while the Radicals led by Cobden and Bright pushed for it. Since party loyalties were loose, members of Parliament frequently changed sides without discredit. Cabinets usually included more than one faction and often changed their members to obtain a majority. As a result little controversial legislation was passed in these years as compared to the preceding or the succeeding decades. In general, foreign affairs dominated British politics throughout these years more than any single domestic issue. A major event was the Crimean War (1854–1856) fought by Britain and France against Russia. It had huge public support, and Lord Palmerston was immensely popular as the Foreign Minister. However, the people were unaware that the country’s army and navy were in a state of decay. The two years brought practically nothing but disaster. By the Treaty of Paris (1856) Britain only succeeded in halting the further expansion of Russia. The government was seen to be made up of incompetent aristocrats and the war brought about its downfall. Palmerston, who had succeeded Lord Aberdeen as Prime Minister in 1855, was forced to accept an inquiry into the conduct of the war. Thus, one of the results of the war was the reform of the British army. Another was the founding of the Red Cross, an outcome of Florence Nightingale’s heroic nursing efforts in the field hospitals during the war. Incidentally, owing to Florence Nightingale the perception of the role of women in society began to change.

In the late 18th and the early 19th century the classical norm began to give way to become just one possibility in a repertory of styles which ranged from Greek revival (the British Museum) to Chinese, from Tudor to exotic Indian style. This meant that style was chosen according to the purpose and site of a building, as well as the aesthetic preferences of the person who commissioned it. The Picturesque, as the new aesthetic direction is often called, was never a precise style, for its aim was rather to create a building and a landscape drawing on the whole catalogue of historical styles. The Picturesque was a stage-set for romantic action. Among the finest examples are the Royal Pavilion in Brighton built for the Prince Regent in the Indian style [83] and Harlaxton Manor [86] designed by Anthony Salvin in the 1830s to replace the original Elizabethan manor house. Harlaxton is an exuberant merging of Gothic, Jacobean and Baroque styles.

In the late 18th and the early 19th century the classical norm began to give way to become just one possibility in a repertory of styles which ranged from Greek revival (the British Museum) to Chinese, from Tudor to exotic Indian style. This meant that style was chosen according to the purpose and site of a building, as well as the aesthetic preferences of the person who commissioned it. The Picturesque, as the new aesthetic direction is often called, was never a precise style, for its aim was rather to create a building and a landscape drawing on the whole catalogue of historical styles. The Picturesque was a stage-set for romantic action. Among the finest examples are the Royal Pavilion in Brighton built for the Prince Regent in the Indian style [83] and Harlaxton Manor [86] designed by Anthony Salvin in the 1830s to replace the original Elizabethan manor house. Harlaxton is an exuberant merging of Gothic, Jacobean and Baroque styles.

71

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The building of Strawberry Hill for Horace Walpole in the second half of the 18th century pioneered the Gothic Revival style. James Wyatt was the first architect to focus on the Gothic Revival – as early as the 1780s, when he designed Lee Priory in Kent. The style was to become popular as Gothic castles arose all over the country. In 1801–1813 Wyatt remodeled Belvoir Castle [84] for the Duke of Rutland, while his nephew did the remodeling of Windsor Castle for George IV in the 1820s. By 1830 the Gothic Revival style had become dominant. A whole generation of architects abandoned the centuries-old classical repertory and started rebuilding the Middle Ages. When in 1834 the Palace of Westminster burnt down, the 1835 competition, won by Sir Charles Barry, stipulated from the outset that the new Houses of Parliament must be Gothic. In 1843 Pugin narrowed the taste still further, opting for the 14th century Decorated Gothic, a decision which was to result in the building of literally hundreds of churches in the style. At the same time Gothic blossomed in the industrial cities which vied with each other in the erection of magnificent town halls, art galleries, museums and public offices. This was an architecture that was proudly insular, patriotic and romantic.

The mid-Victorian period, when political allegiances were confused and fluid, and reform was secondary to foreign affairs, drew to a close around 1865. Britain moved into a new age of transition and reform, an age of High Victorianism. The first change concerned the monarchy and started in 1861, when Victoria’s husband died of typhoid fever. The sudden and unexpected death of the Prince Consort led his widow to seclude herself for twenty years from public life. However, though she didn’t afterwards take as prominent a part in public life as before, she never neglected any of her essential duties as queen, tenaciously holding on to power, playing an important, if hidden, role in the political life of the country and eventually emerging as the most constitutional monarch Britain had seen, a symbol of the whole Victorian era. Ironically, the revival of the fortunes of the monarchy was made possible precisely because of the queen’s apparent withdrawal from her political role. By the 1870s she was beginning to be viewed in a different light due to the longevity of her reign, her domestic virtues, her role through the marriages of her many children as the matriarch of Europe, as well as being the focus of the greatest empire in the world. In 1876 Victoria was made Empress of India. The monarchy became the symbol of stability, tradition and Empire. The Crown was now destined to display pageantry and splendour for all classes, and that was to be deliberately built up and inflated. The process began with the celebration first of Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, and then her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. People could now travel to see the spectacles, read about them in newspapers, see photographs. Victoria was in fact the first media queen.

The second major change is connected with the two main parties that reinvented themselves in response to the new political and social conditions. Both were fortunate in being able to enter the new age with two political giants as their leaders, men whose different personalities were so powerful that that they divided people into one camp or the other. In 1859 the Peelites came together with the Whigs, Liberals and Radicals to form the future Liberal party, with Palmerston as the Prime Minister and Gladstone as a major force in the party. Palmerston died in 1865, and for nearly thirty years Gladstone was to be the leader of the Liberals and the ‘conscience of England’. He was a man of high principle, deeply religious, and his appeal to morality fit the spirit of the times. Gladstone’s political and moral creed defined the philosophy of British Liberalism. The Liberals believed in economic freedom, evolutionary reform, free market and merit as against birth as the true basis of society. Gladstone was to serve as Prime Minister for four terms (1868–1874; 1880– 1885; 1886; 1892–1894); his last ministry came about when he was eighty-three.

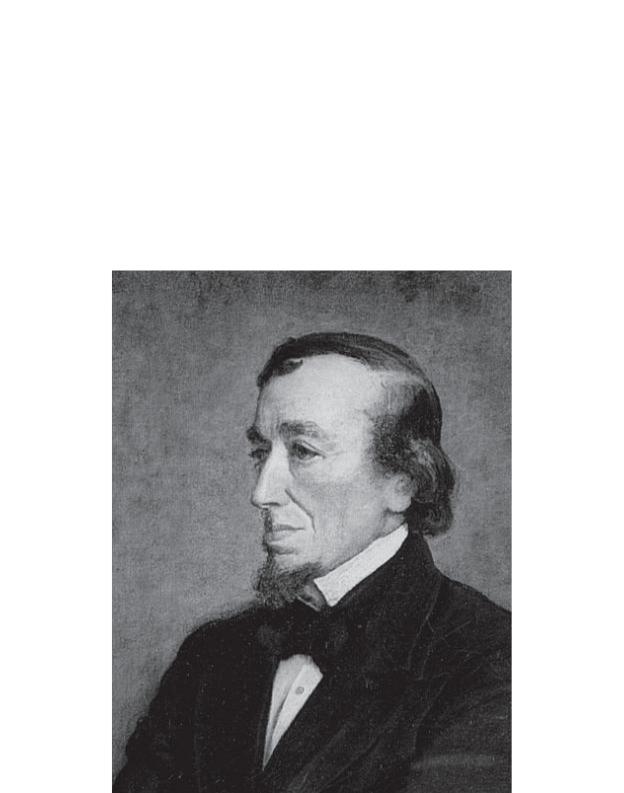

Benjamin Disraeli, the man who rescued the Conservative party from the political wilderness and Gladstone’s rival, had a very different personality. He was ambitious and amoral, and a great

72

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

showman. His pride in England’s national institutions and unabashed imperialism caught the admiration of his colleagues and of Queen Victoria. Disraeli took a vital interest in social legislation and renovated the party’s aristocratic traditions to changing times. His reverence for things past was to become an essential element of a Conservatism that saw its role as the preserver of the existing order of things centred around throne, altar and empire. The Conservative party was the party of the establishment and of property. It was Disraeli who had Parliament confer the title of Empress of India upon Queen Victoria. In turn, Victoria confided in Disraeli as she had done with no other Prime Minister since Melbourne. Her open dislike for Palmerston and Gladstone was now contrasted to her unconcealed partiality for Disraeli and the Conservatives. It was he who was able to persuade the queen to abandon her seclusion and return to public life. In 1876 Victoria elevated Disraeli to the peerage as Earl of Beaconsfield.

Benjamin Disraeli

The Victorian compromise of the Palmerstonian era which was based on the alliance of the aristocracy with the middle class was now gradually expanded to permit the extension of political democracy. By the 1860s British society was very different, and the leaders of both parties developed an understanding that a new extension of franchise was called for. It was felt that it would be wiser to extend the voting rights (still regarded not as a birthright but as a privilege) at a time of general prosperity and an absence of pressure from below rather than wait for social unrest. However, the bill introduced by Gladstone was defeated in 1866, and the Liberal ministry

73

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

headed by Lord Russell fell, to be replaced by a Conservative one with the Earl of Derby as Prime Minister. Disraeli, the driving force in his party, understood that it would never win popularity so long as it was regarded as the party only of landowners. He thus decided to preempt the Liberals’ role as reformers. Disraeli persuaded his party to back reform, thereby robbing the Liberals of their programme and winning the gratitude of workers. Gladstone was enraged over Disraeli’s tactic, but the Second Reform Bill passed with the assistance of the radical wing of the Liberal party in 1867. The franchise was given to town workers (every male householder in a borough who paid rates (taxes)); the electorate was doubled: now two people in five had the right to vote. A huge electorate running into millions called for the development of party machines on a large scale, with a central office and local party associations. A new type of politician was also required, men with powers of public oratory and charismatic personality. Election campaigns developed, with posters, leaflets and meetings to attract the voters. In 1867 the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations was formed, followed three years later by the establishment of a Central Office. Within the Commons a new post appeared, that of Chief Whip, whose task was to see that all Tory MPs adhered to the party line. The Liberal party formed the National Liberal foundation in 1877.

In 1872 the secret ballot was introduced. In 1884–1885 Gladstone introduced and Parliament passed the Third Reform Bill. It extended the franchise to all householders in the county (agricultural workers). With this act, two out of every three males became eligible to vote (nationwide, 8 million people out of 45 million). The second part of the act redistributed parliamentary seats and made Britain a parliamentary democracy. It abandoned the ancient principle of representation by counties and boroughs, where the aristocracy and landowners could often determine the representation. Instead, it established single-member constituencies with representation based on population. The membership in the House of Commons was increased to 670. Thus party organization and the extension of the vote largely ended the historic influence of the aristocracy and landed interests.

By 1875 the earlier liberal philosophy, with its accent on competitive individualism, self improvement through private initiative, and minimal government regulation of trade and industry, had given way to a majority viewpoint favouring regulative legislation that could improve society where private initiative was inadequate or indifferent. The idea that the state had any role at all to play in solving social problems was in itself new. But once state intervention had begun it tended to grow, until in the next century virtually every aspect of daily life came under control. Both the Liberals and the Conservatives now channelled their energies into social legislation. There were to be three main areas of intervention – the poor relief, public health and the education of the lower classes. As for the poor relief, the country was divided into areas, each of which had a Board of Guardians elected by the ratepayers under whose supervision workhouses were to be built and other forms of relief provided.

By passing the Local Government and Public Health Acts of 1871 and 1872 the state accepted that it had a role to play in the prevention of disease. In the field of education Forster’s Education Act (1870) laid down that the state had a duty to provide schools so that no child should be denied an education. In 1880 school attendance was made compulsory, in 1891 elementary education was to be free, and eight years later the school-leaving age was set down at twelve.

In 1888 a Local Government Act set up sixty-two elected county councils which took over from justices of the peace the management of roads, asylums and the local police. The following year the London County Council was created. In 1896 powers were given to local councils to build council houses.

A distinctive feature of Victorian society in this period was that there was no group confrontation of classes. The idea of hierarchy was universally accepted. What held society together was deference, by which was meant the acceptance by each rank of its place within a ladder which

74

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

had its summit in the monarchy, a symbol of national unity. There was a prevalent belief that a government couldn’t pursue any moral policies which were not firmly based on Christian dogma. The basic teaching of Christianity was accepted at all levels of society, even by those who never went near a church.

Another common ground was respectability. It embodied financial independence achieved through one’s own efforts and self-discipline. Respectability brought with it a cult of work and deep respect for home and family. The concept of a good respectable man cut across all social boundaries. Those who were not respectable were the extravagant, the unreliable, the drunkard, the passive, and those who lived off the state.

If the queen, deference, religion and respectability drew classes together, so too did philanthropy and good works. There was a universal horror of state provision, and charity was an obligation laid by convention on every class that was wealthy enough. The philanthropy of Victorian Britain by far exceeded that of any other European country.

Disraeli was shrewd enough to sense that, apart from social reform, another powerful and popular force of the future would be imperialism. He thus actively supported colonial expansion and believed in Britain’s imperial destiny. Up until the 1870s the Empire had been an administrative mechanism in the interests of commerce. Colonies were looked upon as expensive and burdensome necessities best dealt with by allowing them self-government, which was cheaper. However, after that date the atmosphere began to change as the age of the superpower arrived, when virtually every European nation attempted to build up a colonial empire. In the case of Britain renewed expansion began with Disraeli’s purchase in 1875 of the controlling shares in the Suez Canal, a strategic route to India. This was to have the effect of involving Britain first in the fate of Egypt, and gradually more and more in that of the whole of Africa, which had begun to be opened up to Europeans during the 1850s and 60s through the work of explorers like David Livingstone. The temporary occupation of Egypt by the British became permanent in 1882. In order to protect Egypt, neighbouring Sudan had to be conquered. During the 1890s came Zanzibar, Nigeria, Gold Coast (Ghana), Gambia and Sierra Leone. Between 1870 and 1900 sixty million people and fortyfive million square miles were added to the British Empire. In 1890 Queen Victoria reigned over four hundred million people inhabiting a fifth of the surface of the globe. The Empire was firmly linked to the economy, offering new markets and a source for raw materials to the most highly industrialized country in the world.

Gladstone’s wish to retreat gracefully from Disraeli’s expansionist policies proved impossible to fulfill. In the scramble for colonies in the 1880s no major European power could remain unaffected. Gladstone, on principle, hesitated to use force on a lesser power and, therefore, usually used force too late and even more fully, because his initial hesitation had frequently increased the disorder. The ambivalence of Gladstone’s approach caused serious problems in the south of Africa. There were two British colonies there, Cape Colony and Natal, that were adjacent to two Boer states, Orange Free State and Transvaal, settled long before (in the 17th century) by the Boers, descendants of Dutch and French Calvinists. The Boer states were annexed by Britain in 1877, and this annexation was fervently denounced by Gladstone when out of power. Thus, when he took office in 1880, the Boers expected him to repudiate the annexation. Gladstone, however, claimed that British sovereignty was essential to law and order and to the protection of the native tribes. The result was a rebellion and a defeat of a British detachment in 1881. Although the British public opinion demanded retaliation, Gladstone concluded peace negotiations, which granted the Boers independence, storing up problems for the future, as it happened just a few years before gold and diamonds were discovered in the Transvaal.

Meanwhile the Liberals faced the Irish Home Rule challenge. Under the Act of Union of 1801 Ireland was formally joined to Britain and represented in the British Parliament. Supporters of Home Rule for Ireland wanted the undoing of the Act and the restoration of an Irish Parliament

75

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

within the British Empire. Gradually Gladstone came to believe that Home Rule was a moral necessity. The effect on the Liberal party was catastrophic. It was divided right down the middle, and those who regarded Gladstone’s conversion as an act of betrayal allied with the rapidly emerging opponents to such a move in Ulster (where Protestants formed a majority), known as Unionists. To Unionists, Home Rule meant domination by the Catholic agricultural south of Ireland, infected, as they believed, with popery. When Gladstone introduced the first Home Rule Bill for Ireland in June 1886 he was deserted by Liberal Unionists, who joined the Conservatives and defeated the bill. Gladstone lost the next election and the new Conservative Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, appointed his nephew A.J.Balfour as Secretary for Ireland. Thus the Conservatives began two decades of power by keeping their rural constituencies and by gradually winning from the Liberals the urban middle class and the manufacturers. In their opposition to Gladstone’s Irish programme almost the entire Whig aristocracy in the Lords deserted the Liberal party and gave the Conservatives a permanent and irremovable majority in the House of Lords. The English middle class was largely opposed to Irish Home Rule and supported the Tories on this matter. For most of the two decades (1886–1905) Lord Salisbury and then his nephew Balfour (Prime Minister 1902– 1905) gave the country what it seemed to want: efficient government at home, imperialism abroad, and opposition to the Irish Home Rule. The Liberals remained divided and dispirited until 1905, and Gladstone’s attempt during his fourth and last term in office (1892–1894) to pass a second Home Rule Bill failed.

In the last decades of the 19th century relations between Boers and Britons worsened. The discovery of gold and diamonds in Transvaal had brought there a lot of foreigners, many of whom where Britons. War erupted over the Boer treatment of the ‘uitlanders’, as the foreigners were called. The Boer War was to last three years (1899–1902). It began disastrously for Britain and only gradually moved towards victory with the taking of Pretoria in June 1900. However, two more years of guerilla warfare followed until peace was finally made at Vereeniging. The Boers were subjugated and their two states annexed to form the Union of South Africa. Yet, the Boer war isolated the country diplomatically, cost Ј300 million and claimed the lives of 30,000 men.

76