- •От автора

- •Glimpses of British History

- •Early Britain

- •The House of Normandy

- •Medieval England

- •Tudor England

- •The Stuarts

- •Georgian Britain

- •Victorian Britain

- •Edwardian Britain

- •Britain and the two World Wars

- •Britain after World War II

- •Modern Britain

- •Modern British Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •The House of Lords

- •The House of Commons

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses and British Heritage

- •Glossary

- •British History

- •Modern Britain

- •The Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •Elections

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses

- •Architecture

- •Key to some phonetic symbols:

- •Bibliography

- •Dictionaries Used

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

British Parliament

Parliament, often referred to as Westminster, is the supreme law-making authority that can legislate for the United Kingdom as a whole or for any parts of it separately. The main functions of Parliament are to pass laws, to vote taxation and to scrutinize government policy.

British Parliament consists of two Houses: the unelected upper house, the House of Lords, and the elected lower house, the House of Commons. The House of Commons is the centre of parliamentary power. It is directly responsible to the electorate, and from the 20th century the House of Lords has recognised the supremacy of the elected chamber. Although the House of Commons is traditionally regarded as the lower house, it is the main parliamentary arena for political battle. A Government can only remain in office for as long as it has the support of a majority in the House of Commons. Like the House of Lords, the House of Commons debates new primary legislation as part of the process of making an Act of Parliament, but the Commons has primacy over the non-elected House of Lords. ‘Money bills’, concerned solely with taxation and public expenditure, are always introduced in the Commons and must be passed by the Lords promptly and without amendment. When the two houses disagree on a non-money bill, the Parliament Act can be invoked to ensure that the will of the elected chamber prevails. So far two Parliament Acts have been used: the first in 1911 and the second in 1949. Parliament Acts allow for a bill to become law without the agreement of the Lords when certain conditions have been met: the bill has been introduced and passed in the Commons in two consecutive sessions and the Lords have on both occasions actively prevented its passing.

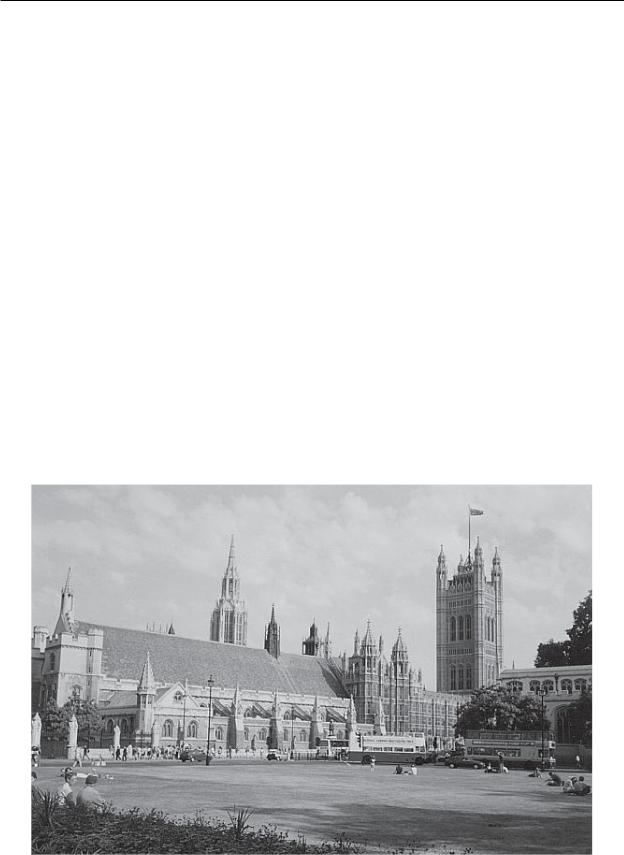

The Houses of Parliament

Parliamentary procedure is based on custom and precedent. The system of debate in the two Houses is similar. Each Parliament is divided into annual sessions with breaks for public holidays and a long summer ‘recess’.

160

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The House of Lords

The House of Lords is an institution with a long and illustrious past, but a rather more uncertain future. Until the reforms of 1999, it was the largest regularly sitting legislative body in the world: more than 1,200 people (most of them hereditary peers) were entitled to sit and vote there, though in practice many hereditary peers chose not to exercise their rights. In 1999 about 600 hereditary peers were evicted from the house, so that now its membership is different from what it was before 1999, and is likely to change further as the Labour government has repeatedly announced its intention to remove the last remaining hereditary peers from the upper house (as, for example, in its 2005 election manifesto).

Traditionally all the members are divided into Lords Temporal and Lords Spiritual. The Lords Spiritual include 2 Archbishops (the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York), the bishops of London, Winchester and Durham and 21 senior diocesan bishops of the Church of England. When the bishops retire from their sees at the age of seventy they cease to be members.

The Lords Temporal are hereditary peers, life peers and Law Lords. The majority of the remaining 92 hereditary peers were chosen among all the hereditary peers in a series of elections held by their party groups. If a remaining hereditary peer dies, the right to a seat is given to the next party candidate. Some of the remaining hereditary peers are office holders (chairmen of committees, for example) elected by the whole house, two of them are royal office holders who hold their offices for life: the Earl Marshal (Duke of Norfolk) and the Lord Great Chamberlain (Marquis of Cholmondeley).

Life peers are elevated to the peerage by the monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister. Opposition party leaders can also nominate their candidates via the Prime Minister. Besides, there is an Appointments Commission charged with making independent non-party nominations of socalled ‘people’s peers’. The People’s Peers idea put forward by Blair’s government was supposed to bring fresh talent to the Lords by inviting applications from members of the public and creating new independent non-party peers. After the Commission was the set up in 2000 there were more than 3,000 applications, but when the first set of 15 people’s peers was announced in April 2001, there was much disappointment as it consisted exclusively of establishment figures. Although after 2001 the Commission has occasionally passed names to the Prime Minister for nomination, there is now much less enthusiasm among the public and extensive criticism of the whole idea.

Now there are about 600 life peers in the Lords, new life peerages are announced each year in the honours’lists. More than one hundred and fifty new peers have been created since 1999, most of them Labour, so that now Labour peers have a majority over the other groups of life peers: Conservative, Liberal Democratic and independent ones (crossbenchers). However, this majority is not great enough to prevent Conservative, Liberal Democratic and crossbench peers combining to block government measures.

The Lords Temporal also include the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, a group of individuals appointed to the House of Lords so that they may exercise its judicial functions. Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, more commonly known as Law Lords, are selected by the Prime Minister, but are formally appointed by the Sovereign. A Lord of Appeal in Ordinary must retire at the age of 70, or, if his or her term is extended by the Government, at the age of 75; after reaching such an age, a Law Lord cannot hear any further legal cases. The number of Lords of Appeal in Ordinary (excluding those who are no longer able to hear cases due to age restrictions) is limited to twelve. Lords of Appeal in Ordinary traditionally do not participate in political debates, so as to maintain judicial independence. They hold seats in the House of Lords for life, remaining members even after reaching the retirement age of 70 or 75. When the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 comes

161

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

into force, the Lords of Appeal in Ordinary will become judges of the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and will be barred from sitting or voting until they retire as judges.

Unlike the House of Commons, the House of Lords does not elect its own Speaker; the presiding officer is the Lord Chancellor. The Lord Chancellor is not only the Speaker of the House of Lords, but also a member of the Cabinet; his or her department, formerly the Lord Chancellor’s Department, is now called the Department of Constitutional Affairs. In addition, the Lord Chancellor is the head of the judiciary of England and Wales, serving as the President of the Supreme Court of England and Wales. Thus, the Lord Chancellor is part of all three branches of Government: the legislative, the executive, and the judicial. In June 2003, the Blair Government announced its intention to abolish the post of Lord Chancellor, due to the office’s mixed executive and judicial functions; however, the abolition of the office was rejected by the House of Lords, and the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 preserves the office of Lord Chancellor.

When presiding over the House of Lords, the Lord Chancellor wears a ceremonial black and gold robe. The Lord Chancellor or Deputy Speaker sits on the Woolsack, a large red seat stuffed with wool, at the front of the Lords Chamber. The Lord Chancellor has little power compared to the Speaker of the House of Commons. He or she only acts as the mouthpiece of the House, performing duties such as announcing the results of votes. The Lord Chancellor cannot determine which members may speak, or keep order in the House; these measures may be taken only by the House itself. Unlike the politically neutral Speaker of the House of Commons, the Lord Chancellor and Deputy Speakers remain members of their respective parties, and may take part in debate.

Another major officer is the Leader of the House of Lords, a peer selected by the Prime Minister. The Leader of the House is responsible for steering Government bills through the House of Lords, and is a member of the Cabinet. The Leader also advises the House on proper procedure when necessary, but such advice is merely informal, rather than official and binding. The Clerk of the Parliaments is the chief clerk and officer of the House of Lords appointed by the Crown. The Clerk advises the Lord Chancellor on the rules of the House, signs orders and official communications, endorses bills, and is the keeper of the official records of both Houses of Parliament. Moreover, the Clerk of the Parliaments is responsible for arranging by-elections of hereditary peers when necessary. The Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod is also an officer of the House; he takes his title from the symbol of his office, a black rod. Black Rod (as the Gentleman Usher is normally known) is responsible for ceremonial arrangements, is in charge of the House’s doorkeepers, and may (upon the order of the House) take action to end disorder or disturbance in the Chamber. Black Rod is also Serjeant-at-Arms of the House of Lords, and in this capacity attends upon the Lord Chancellor.

The Lords Chamber is lavishly decorated, in contrast with the more modestly furnished Commons Chamber. Benches in the Lords Chamber are coloured red. The Woolsack is at the front of the Chamber; supporters of the Government sit on benches on the right of the Woolsack, while members of the Opposition sit on the left. Non-party members, known as cross-benchers, sit on the benches immediately opposite the Woolsack. The Lords Chamber also has the Throne from which the Sovereign delivers a speech outlining the Government’s agenda for the upcoming parliamentary session.

Speeches in the House of Lords are addressed to the House as a whole (“My Lords”) rather than to the presiding officer alone (as is the custom in the Commons). Members may not refer to each other in the second person (as “you”), but rather use third person forms such as “the noble Duke”, “the noble Earl”, “the noble Lord”, “my noble friend”, etc. Each member may make no more than one speech on a motion, except that the mover of the motion may make one speech at the beginning of the debate and another at the end. Speeches are not subject to any time limits in the House; however, the House may put an end to a speech by approving a motion “that the noble Lord be no longer heard”. It is also possible for the House to end the debate entirely, by

162

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

approving a motion “that the Question be now put”. Once all speeches on a motion have concluded the motion may be put to a vote. The House first votes by voice vote; the Lord Chancellor or Deputy Speaker puts the question, and the Lords respond either “Content” (in favour of the motion) or “Not-Content” (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote, but if his assessment is challenged by any Lord, a recorded vote known as a division follows. Members of the House enter one of two lobbies (the “Content” lobby or the “Not-Content” lobby) on either side of the Chamber, where their names are recorded by clerks. At each lobby are two Tellers (themselves members of the House) who count the votes of the Lords. The Lord Chancellor or Deputy Speaker may vote from the Woolsack. Once the division finishes, the Tellers provide the results to the presiding officer, who then announces them to the House.

The main functions of the House of Lords are:

•scrutinising bills that have already been debated in the Commons; the Lords makes about 2,000 amendmends to bills a year

•questioning government ministers at regular Question Times

•providing expertise through specialist select committees

•initiating legislation that is subsequently debated in the Commons

The legislative powers of the House of Lords have been greatly reduced by the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949: it has the power to delay public bills for a year from their first second reading in the Commons, to send a bill to a select committee for further scrutiny, or to amend a bill. Members of the Lords do not receive any salary, but are entitled to reimbursement of travelling expenses on parliamentary business within the UK and certain other expenses connected with attendance at sittings. Since the majority of hereditary peers were removed from the Lords in 1999 the reform has stalled. A Joint Committee was established in 2001 to resolve the issue, but it reached no conclusion and instead gave Parliament seven options to choose from (a fully appointed house, 20 % elected, 40 % elected, 50 % elected, 60 % elected, 80 %, and fully elected). In a confusing series of votes in February 2003 all of these options were defeated, although the 80 % elected option fell by just three votes. MPs favouring outright abolition voted against all the options. New peers, therefore, are only created by appointment to the house.The Labour Party now intends to proceed with the second stage of the reform early in the next Parliament, although they are yet to state exactly what system they will be proposing. The Conservative Party favour an eighty per cent elected Second Chamber, while the Liberal Democrats are calling for a fully elected Senate. In the run up to the 2005 general election a cross-party campaign initiative ‘Elect the Lords’ was set up to make the case for a predominantly elected Second Chamber. The post-election Queen’s speech saw an announcement that the government “will bring forward proposals to continue the reform of the House of Lords” in the 2005/2006 legislative session.

The House of Commons

The term “Member of Parliament” (MP) is normally used only to refer to Members of the House of Commons, even though the House of Lords is also part of Parliament. Each Member of Parliament represents a single constituency. The reforms of 1885 abolished most twomember constituencies; the few that remained were all abolished in 1948. The boundaries of the constituencies are determined by four permanent and independent Boundary Commissions, one each for England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. The number of constituencies assigned to the four parts of the United Kingdom is based roughly on population. Currently the United Kingdom is divided into 646 constituencies, with 529 in England, 40 in Wales, 59 in Scotland, and 18 in Northern Ireland.

163

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

General (parliamentary) elections occur whenever Parliament is dissolved by the Sovereign. The timing of the dissolution is normally chosen by the Prime Minister; normally, however, a parliamentary term may not last for more than five years. It happens only in exceptional circumstances (such as during the two world wars), and a special bill extending the life of Parliament is required to pass both Houses and receive the royal assent. The House of Lords, exceptionally, retains its power of veto over such a bill. In practice, elections are called before the end of the five-year term. The timing reflects political considerations, and is generally most convenient for the Prime Minister’s party. Voting usually takes place within 17 days of the dissolution, not including Saturdays and Sundays and public holidays: therefore, election campaigns last for three to four weeks.

All British citizens may vote provided they are aged 18 years or over and are not legally barred from voting. In order to vote, one must be a resident of the United Kingdom as well as a citizen of the United Kingdom, of a British overseas territory, of the Republic of Ireland, or of a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Also, British citizens living abroad are allowed to vote for fifteen years after moving from the United Kingdom. No voter may vote in more than one constituency.Voting in elections is voluntary.

Each candidate must submit nomination papers signed by ten registered voters from the constituency, and pay a deposit of Ј500, which is refunded only if the candidate wins at least five per cent of the vote. The deposit seeks to discourage irresponsible candidates. People under 21, members of the House of Lords and the clergy, prisoners, insane persons and a range of public servants and officials are not qualified to become Members. Candidates normaly belong to one of the main political parties. However, smaller political parties and groups also put forward candidates, and individuals without party support can also stand. Since WWII the great majority of MPs have belonged to either the Conservative or the Labour party, but now there is also an influential and increasingly popular Liberal Democratic party. The parties have their colours, which can be seen on the badges that party activists wear during election campaigns and on parliamentary maps showing the constituencies by party. The Conservative colour is blue, the Labour is red, and the Liberal Democrats are orange. There are also nationalist parties from Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

Each constituency returns one Member; the First-Past-the-Post electoral system, under which the candidate with a plurality of votes wins, is used. Once elected, the Member of Parliament normally continues to serve until the next dissolution of Parliament or until death. If a Member, however, ceases to be qualified, his or her seat falls vacant. It is possible for the House of Commons to expel a Member, but this power is only exercised when the Member has engaged in serious misconduct or criminal activity. In each case, a vacancy may be filled by a by-election in the appropriate constituency. The same electoral system is used as in general elections.

Following a general election the party that has won a majority in the Commons forms a government, and its leader is appointed Prime Minister by the Queen. If none of the parties has an overall majority the result will be a hung Parliament, which is a source of great political instability, for if the leader of the largest party faction fails to cut a deal with enough minority parties and receive a vote of confidence when he presents his party’s legislative programme to the House, Parliament will have to be dissolved and a new election called. The last election (May 2005) gave Labour a majority of 66 seats: it has 354 seats to 196 Conservative and 62 Liberal Democrats.

Like the House of Lords, the House of Commons meets in the Palace of Westminster in London. The Commons Chamber is small and modestly decorated in green. There are five rows of benches on two sides of the Chamber, divided by a centre aisle. The Speaker’s chair is at one end of the Chamber; in front of it is the Table of the House, on which the Mace rests. The Clerks sit at one end of the Table, close to the Speaker so that they may advise him or her on procedure when necessary. Members of the Government sit on the benches on the Speaker’s right, while members

164

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

of the Opposition occupy the benches on the Speaker’s left. In front of each set of benches, a red line is drawn on the carpet. The red lines in front of the two sets of benches are two-sword lengths apart; a Member is traditionally not allowed to cross the line during debates, for he or she is then supposed to be able to attack an individual on the opposite side. Government ministers and important Opposition leaders (the Shadow Cabinet of the largest Opposition party) sit on the front rows, and are known as “frontbenchers.” Other Members of Parliament, in contrast, are known as “backbenchers.” Like in the Lords, there are also independent crossbenchers. Oddly enough, all Members of Parliament cannot fit in the Chamber, which can only seat 437 of the 646 Members. Members who arrive late must stand near the entrance of the House if they wish to listen to debates. Sittings in the Chamber are held each day from Monday to Thursday, and also on some Fridays. During times of national emergency, the House may also sit on Saturdays.

Sittings of the House are open to the public (members of the general public and tourists may come and sit in the Strangers Gallery), but the House may at any time vote to sit in private. Traditionally, a Member who desired that the House sit privately could shout “I spy strangers,” and a vote would automatically follow. More often, however, this device was used to delay and disrupt debates; it was abolished in 1998. Now, Members seeking that the House sit in private must make a formal motion to that effect. Public debates are broadcast on the radio, and on television by BBC Parliament, and are recorded in Hansard (an official report of the proccedings of the British Parliament, named after L.Hansard and his descendants, who compiled the reports until 1889).

The House of Commons elects a presiding officer, known as the Speaker, at the beginning of each new parliamentary term, and also whenever a vacancy arises. If the incumbent Speaker seeks a new term, the House may re-elect him or her merely by passing a motion; otherwise, a secret ballot is held. A Speaker-elect cannot take office until he or she has been approved by the Sovereign. The Speaker is assisted by three Deputy Speakers. The Speaker and the Deputy Speakers are always Members of the House of Commons.When presiding, the Speaker or Deputy Speaker wears a ceremonial black and gold robe. The presiding officer may also wear a wig, but this tradition has been abandoned by the present Speaker Michael Martin. The Speaker oversees the day-to- day running of the House, controls debates by calling on Members to speak, and puts the question to vote. If a Member believes that a rule (or Standing Order) has been breached, he or she may raise a “point of order,” on which the Speaker makes a ruling that is not subject to any appeal. The Speaker may discipline Members who fail to observe the rules of the House. Customarily, the Speaker and the Deputy Speakers are non-partisan; they normally do not vote, do not speak in debates or participate in the affairs of any political party.

The Prime Minister selects the Leader of the House of Commons, who is responsible for steering Government bills through the House, and is a member of the Cabinet. On behalf of the Government, the Leader manages the schedule of the House of Commons, and makes announcements relating to the timing of recesses, bills, and important events.

The Clerk of the House is the chief clerk and officer of the House of Commons (but is not a member of the House itself). The Clerk advises the Speaker on the rules and procedure of the House, signs orders and official communications, and signs and endorses bills. The Clerk’s deputy is known as the Clerk Assistant. Another officer of the House is the Serjeant-at-Arms, whose duties include the maintenance of law, order, and security on the House’s premises. The Serjeant-at-Arms carries the ceremonial Mace, a symbol of the authority of the Crown and of the House of Commons, into the House each day in front of the Speaker. The Mace is laid upon the Table of the House of Commons during sittings.

Every party has its Whips, or party policemen, who discipline and press Members to vote in accordance with the party line. Whips also secure the attendance of Members of their party in Parliament, particularly on the occasion of an important vote. They normally hold the keys to promotion and favours: from knighthoods to jobs in the government.

165

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The annual salary of each MP is Ј57,485; MPs may receive additional salaries if they hold offices in the House (for instance, the Speakership). Most Members also claim between Ј100,000 and Ј150,000 for various office expenses (staff costs, postage, travelling, etc) and also for the costs of maintaining a home in London in the case of non-London Members.

During debates, Members may only speak if called upon by the Speaker. Traditionally, the presiding officer alternates between calling Members from the Government and Opposition. Speeches are addressed to the presiding officer, using the words “Mr Speaker,” “Madam Speaker,” “Mr Deputy Speaker,” or “Madam Deputy Speaker.” Only the presiding officer may be directly addressed in speeches; other Members must be referred to in the third person. Traditionally, Members do not refer to each other by name, but by constituency, using forms such as “the Honourable Member for [constituency]”. The Standing Orders of the House of Commons do not establish any formal time limits for debates. The Speaker may, however, order a Member who persists in making a tediously repetitive or irrelevant speech to stop speaking. The time set aside for debate on a particular motion is, however, often limited by informal agreements between the parties. Debate may, however, be restricted by the passage of “Allocation of Time Motions”, which are more commonly known as “Guillotine Motions.” Alternatively, the House may put an immediate end to debate by passing a motion to invoke the Closure. The Speaker is allowed to deny the motion if he or she believes that it infringes upon the rights of the minority.

Each parliamentary session begins with the State Opening of Parliament. The Queen’s speech is drafted by her government and read from the Throne in the Lords chamber to members of both Houses. During the next five or so days the government and opposition debate aspects of the Queen’s speech in the Commons, and vote on the amendments which the opposition proposes. Since the speech is a statement of policy, defeat on any such vote would oblige the government to resign.

Parliamentary procedure is based on custom and precedent, partly codified by each House in its Standing Orders. Each day begins with Question Time (one hour): MPs ask ministers and other MPs questions. These questions must be handed in 48 hours in advance for the ministers to prepare an answer. Once an answer has been given a supplementary question(s) may be asked. On Wednesdays the Prime Minister answers questions on general policy matters.

After Question Time the main debate takes place. Time is given on twenty-four days during a session for individual backbenchers to introduce Private Members’ Bills. However, most of the time available is devoted to scrutiny of government spending and debating public bills introduced by government ministers. The system of debate is similar in both Houses. Every subject starts off as a proposal or ‘motion’ made by a member. The Speaker then proposes the question as a subject of debate.When the debate concludes, or when the Closure is invoked, the motion in question is put to a vote. The House first votes by voice vote; the Speaker or Deputy Speaker puts the question, and MPs respond either “Aye” (in favour of the motion) or “No” (against the motion). The presiding officer then announces the result of the voice vote, but if his or her assessment is challenged by any Member, a division follows. If a division does occur, Members enter one of two lobbies (the “Aye” lobby or the “No” lobby) on either side of the Chamber, where their names are recorded by clerks. At each lobby are two Tellers (themselves Members of the House) who count the votes of the Members. Once the division concludes, the Tellers provide the results to the presiding officer, who then announces them to the House. If there is an equality of votes, the Speaker or Deputy Speaker has a casting vote. The quorum of the House of Commons is forty members for any vote; if fewer than forty members have participated, the division is invalid.

A bill is normally drafted after exhaustive consultation with professional agencies concerned. Proposals sometimes take the form of ‘white papers’ stating government policy, which can be debated before a bill is introduced. ‘Green papers’ are published when the government wants a full public discussion before it formulates its own proposals.

166

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The process of passing a public bill is similar in both Houses. Its publication in printed form is announced in the chamber, and this announcement is called ‘the first reading’. The second reading, usually a few weeks later, is the occasion for a full debate on the principles of the bill, unless there is general assent that a debate is not needed. If necessary the bill is passed to a committee. The committee stage involves a detailed examination of the bill, clause by clause. The committee also decides if amendments are needed. At the third reading the revised bill is considered in its final form, and a vote is taken if necessary. When the bill has been passed by the Commons it is submitted to the Lords. If passed by the Lords and given the Royal assent the bill becomes an Act of Parliament.

Committees are used for a variety of purposes; one common use is for the review of bills. Committees consider bills in detail, and may make amendments. Bills of great constitutional importance, as well as some important financial measures, are usually sent to the Committee of the Whole House, a body that, as its name suggests, includes all members of the House of Commons. Instead of the Speaker, the Chairman or a Deputy Chairman presides. The Committee meets in the House of Commons Chamber. Most bills are considered by Standing Committees, which consist of between sixteen and fifty members each. The membership of each Standing Committee roughly reflects the standing of the parties in the whole House. Though “standing” may imply permanence, the membership of Standing Committees changes constantly; new Members are assigned each time the Committee considers a new bill. There is no formal limit on the number of Standing Committees, but there are usually only ten. The House of Commons also has several Departmental Select Committees. The membership of these bodies, like that of the Standing Committees, reflects the strength of the parties in the House of Commons. Each committee elects its own Chairman. The primary function of a Departmental Select Committee is to scrutinise and investigate the activities of a particular Government Department; to fulfil these aims, it is permitted to hold hearings and collect evidence. Bills may be referred to Departmental Select Committees, but such a procedure is very seldom used.

167