- •От автора

- •Glimpses of British History

- •Early Britain

- •The House of Normandy

- •Medieval England

- •Tudor England

- •The Stuarts

- •Georgian Britain

- •Victorian Britain

- •Edwardian Britain

- •Britain and the two World Wars

- •Britain after World War II

- •Modern Britain

- •Modern British Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •The House of Lords

- •The House of Commons

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses and British Heritage

- •Glossary

- •British History

- •Modern Britain

- •The Monarchy

- •British Parliament

- •Elections

- •Government

- •Local Government

- •The Legal System

- •Historic Country Houses

- •Architecture

- •Key to some phonetic symbols:

- •Bibliography

- •Dictionaries Used

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

Georgian Britain

When Queen Anne died in 1714 the divisions between the two parties were as bitter as ever and yet the succession went smoothly. In accordance with the terms of the Act of Settlement George, elector of Hanover succeeded to the throne. His mother Sophia had died four months earlier.

The only major threat to the Hanoverian dynasty came from the Jacobites, so when the supporters of James II’s son, the Old Pretender were defeated in Scotland in 1715 the rule of the House of Hanover truly began.

The arrival of George I (1714–1727) brought more stability. Unlike both his predecessors who felt that their power would be eroded if they favoured only one party, the new king didn’t hesitate to make an alliance with the Whigs, who had brought him to power and whose loyalty he didn’t doubt. Since the Jacobite uprising had compromised the Tory party the last remaining Tories were dismissed from the Cabinet and in 1716 the Septennial Act was passed extending the life of Parliaments from 3 to 7 years. This contributed to the Whigs’ ability to establish themselves firmly in power.

The new dynasty wasn’t popular in Britain. George I was honest, dull and diffident. He became king at the age of 54, never learned English, lacked either personal charm or regal bearing and lived only for his German mistresses and for Hanover. His subjects never learned to love or admire him. If they were attached to him, it was largely because he interfered so little with the national institutions and because they didn’t want the return of the Stuarts.

His son, George II (1727–1760) was no improvement on his father, although he at least could speak English. George II was stiff and formal, a man obsessed by regularity and detail, but given to sudden bouts of ill-temper and uncontrolled passion. Both kings, however, were sharply aware of their prerogatives and exercised them to the full. Both George I and II remained at the center of the political stage as the founts of honour and justice, as chief executives and makers of war and peace. They controlled all the major appointments – in the civil service, Church of England, Army and Navy, and retained the right to appoint and dismiss ministers.

58

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

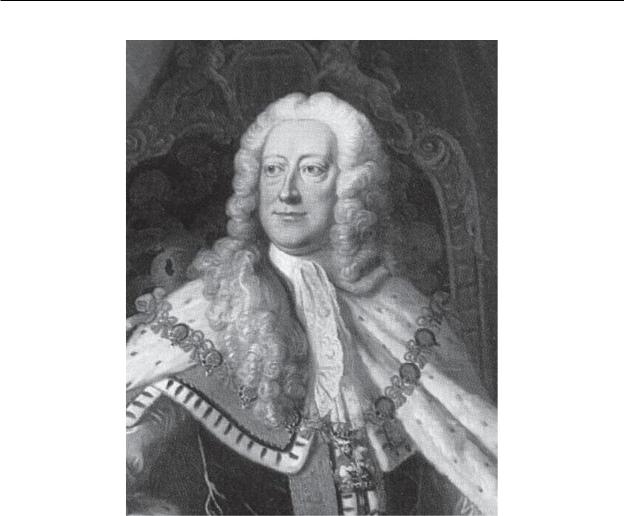

George II

The greatest political figure of the era was Sir Robert Walpole. He became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1721 when he was 44 and was only forced from office in 1742. No other person in his position has ever held power for so long. Walpole worked hard to gain the king’s respect and soon became indispensable. As George I was unable to speak to his ministers in English and didn’t attend Cabinet meetings Walpole effectively ran the Cabinet for him, setting an important precedent. He and the king worked to closely that when George I died in 1727, Walpole wasn’t dismissed.

Walpole realized that the seat of political power for any chief minister was in the Commons. He therefore refused to go to the Lords and remained in the Commons, thus creating a new office, the ancestor of the Prime Minister, the minister for the king in the Commons. Walpole was the first man to play this role, succeeded in the 1740s by Henry Pelham. The term ‘Prime Minister’ came into use initially as a criticism of Walpole for being more prominent in the Cabinet than his colleagues. Walpole and his successors developed an arrangement whereby the Prime Minister and his cabinet colleagues could command sufficient support in the Commons to make sure of a majority. In general it always happened, for the Commons was filled with those who enjoyed royal patronage. Government was stable because enough members of Parliament were, for various reasons, part of the network which brought them benefits if they voted along with the ministry of the day. Parliament was, in effect, one interconnected family with the aristocrats sitting in the Lords and their son, brothers and cousins – in the Commons.

The running of the country increasingly came to depend on the ability to manipulate a few hundred largely interconnected people, the йlite; real power was concentrated in only a few hands, those of the king and a handful of landed aristocratic families who in the main were either Whigs

59

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

or converts. The function of government in the hands of this interconnected circle was confined to maintaining law and order, conducting foreign policy and exerting minimum economic control. The power of the Commons grew steadily during the century without any serious efforts by the Lords to stop the trend, because the political and family interests of the two houses were similar

– they represented the same class.

In 1745 there was another attempt by the Jacobites to regain power. Charles Edward Stuart (nicknamed Bonnie Prince Charlie), the Young Pretender, landed in Scotland to press his father’s claim. His army seized Edinburgh and moved as far south as Derby. Yet he and his Scottish supporters were eventually defeated by the Duke of Cumberland at Culloden Moor in April 1746.

In 1756 Britain got involved in the Seven Years’ War over its colonial and commercial rivalry with France. When the war broke out Britain already had significant colonial possessions, but by the time that peace was made in 1763 she was to emerge with the greatest empire that the world had seen since Rome. The basis of this was the territory inherited from the previous century, the old colonies along the eastern coast of Northern America, 13 states in all; then there were the West Indian Islands: Bermuda, Barbados, Jamaica, etc. Collectively these were fast-growing markets for British products. In 1760 Montreal was taken and French Canada passed into British hands. Although peace came in 3 years, the first British Empire had been created. By the Treaty of Paris (1763) Britain acquired the whole of Canada, Louisiana east of the Mississippi, Cape Breton, Tobago, Senegal and Florida. This mighty triumph owed much to the war minister William Pitt the Elder. Pitt was a new political phenomenon, for he built up popular opinion outside the House. His ability to attract outside support was such that he was called the first minister given by the people to the king, although in reality the king reserved his right to choose and dismiss, so that Pitt had to work in a coalition with the Duke of Newcastle, who as a man more acceptable to the king was officially the Prime Minister (1757–1762).

Georgian architecture is the name given in English-speaking countries to the classical architectural styles current between 1720 and 1840. The Georgian style succeeded the English Baroque of Christopher Wren and John Vanbrugh. The Baroque style, popular in Europe, was never truly to the English taste; considered Tory and Jacobite, it was quickly superseded when, in the first quarter of the 18th century, four books were published in Britain, which highlighted the simplicity and purity of classical architecture. The most popular of these was Vitruvius Britannicus (1715) by Colen Campbell. The arrival of George I and the long decades of Whig rule ensured the victory of the Palladian movement. Sir Christopher Wren was curtly dismissed as Surveyor of the Royal Works to be replaced by Campbell.

Georgian architecture is the name given in English-speaking countries to the classical architectural styles current between 1720 and 1840. The Georgian style succeeded the English Baroque of Christopher Wren and John Vanbrugh. The Baroque style, popular in Europe, was never truly to the English taste; considered Tory and Jacobite, it was quickly superseded when, in the first quarter of the 18th century, four books were published in Britain, which highlighted the simplicity and purity of classical architecture. The most popular of these was Vitruvius Britannicus (1715) by Colen Campbell. The arrival of George I and the long decades of Whig rule ensured the victory of the Palladian movement. Sir Christopher Wren was curtly dismissed as Surveyor of the Royal Works to be replaced by Campbell.

Campbell argued for a national architectural style, fundamentally different from the Baroque, a style that had already been created once, in the simple, noble architecture of Inigo Jones – the British Vitruvius. The return to the works of Jones and Palladio hinges on a fundamental reinterpretation of their style. It is no longer viewed as a symbol of Stuart pretensions. Instead, Palladio is esteemed for adapting the buildings of Roman antiquity to suit a governing class closely linked to the land. The movement, articulate by the time that George I arrived, needed only a rich and powerful patron. It found one in Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington.

After traveling in Italy, Burlington returned to England to devote his life and his fortune to the perfection of the national taste, assisted by his close friend, the painter and architect William Kent. Between them, they dominated domestic architecture in England for the rest of the century. Burlington’s campaign for a

60

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

reformed architectural style was at its height between 1720 and 1750. The earl’s earliest work was at his villa in Chiswick, an elegant classical pavilion [76] Together Kent and Burlington designed Holkham Hall, the Norfolk home of the Whig magnate the Earl of Leicester. In 1730–1736 the extraordinary Assembly Rooms at York were built. As a result the style was to spread, and evidence of it can be seen everywhere in the use of Palladian Venetian windows, coffered vaults, semi-domes, vaulted spaces and niches. Eventually Palladianism was to become a national style.

The main development of Palladianism in Britain came through the work of Sir William Chambers and the Scottish architect Robert Adam. Both were exponents of the emerging neo-classical style which had been originally pioneered by French and Italian architects. Throughout the 1760s and 1770s Chambers was responsible for a whole series of town and country houses; it was he who designed the only major public building of the century, the new Somerset House in the Strand in London. [78] Robert Adam used the style of imperial Rome as a starting point for his own one, often called the ‘Adam style’. A unique synthesis uniting columns and carpets, pedestals and porticos, the Adam style is famous for its variety and its sense of movement. It is especially innovative in the design of interiors. While Palladianism in general had opted for straightforward room-shapes, Adam often uses circular rooms, curved lines, oblong shapes and abundant surface decoration. Adam’s designs are seen at their best at Syon House and Harewood House. [79]

Adam was the first architect to devise an overall integrated look to a house. Following his example houses began to be designed as a single architectural composition. All over Britain squares, crescents and terraces arose in the new neoclassical style, designed by far less important architects or just put up by building companies from pattern books which spread the style across the country and down the social scale. One of the finest examples is the Royal Crescent in Bath. [81] With its monumental curve it became the model for every major housing project for over half a century.

Meanwhile the unexpected death of George II in 1760 was to usher in a very different era. The new king, George III (1760–1820), regarded himself foremost as King of Great Britain,

rather than Elector of Hanover, he had been educated in England and spoke English as his first language. George was a pious Anglican and a devoted husband. He began his reign with an idealism which made him ill-equipped to cope with the tough realities of political life. His two predecessors had been shrewd enough to get on well with ministers who enjoyed long periods of office and who, with the aid of the old duke of Newcastle, could use the Whig connections and sustain a majority in the Commons. George III had been brought up to believe that both Georges before him had been mere puppets in the hands of the Whig oligarchy, which had dominated the political scene for 4 decades. Having exalted ideas of the royal prerogatives he sought to play a more active role by exercising his powers to the full and establishing a system of personal government. Pitt was the first to resign. Then the king lost from the government the old Duke of Newcastle, the key figure in the long period of Whig rule. Newcastle had been the focus of the vast network of Whig families and their connections had been crucial to the working of any administration. For the first time since George I they found themselves fallen from power.

Thus as the old system broke politics entered a period of remarkable instability, much of which was the fault of the new king although the Whig legend of George III as a tyrant seeking to dominate Parliament is clearly exaggerated. The system of personal government proved unsatisfactory because it was unsuccessful and failed to reconcile political factions. George III was

61

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

to spend a decade trying to find a minister of his own liking with whom he could work and who could command a majority in the Commons. None of the constantly changing politicians (there were 7 Prime Ministers from 1760 to 1770) made for firm policy at the top, precisely what was needed as the country slowly drifted towards a major catastrophe, which resulted in the loss of its North American colonies.

There were 13 colonies that were composed of British people, most of them stoutly Protestant. In practice they were answerable to Parliament. Each colony had its own locally elected assembly and a Crown appointed governor, who was paid by the colonists but was answerable to the British government that, in turn, was answerable to Parliament. Crisis came when Parliament began to feel that the colonists should pay taxes to contribute towards the cost of defending them. The colonists thought that since they weren’t represented in Parliament it had no right to impose taxes on them. Thus when in 1765 Parliament decided to impose the first direct tax, the colonial assemblies complained bitterly and there were riots in Boston. The assemblies met in New York and declared that the British Parliament had no right to impose taxes on them. The colonists pressed for the right to govern themselves and began to reject parliamentary legislation. Parliament decided to introduce customs tariffs on paper, paint, tea and other goods. The colonies boycotted the British goods. In 1769 the British Cabinet was forced to yield and suspended all the tariffs, except that on tea.

At this point the king finally found an equivalent of Walpole, Lord North, who was to be Prime Minister for twelve years (1770–1782). Very soon North attracted enough support from various groups and was able to command a sufficient parliamentary majority. But he was to preside over catastrophic events. In December 1773 the Massachusetts patriots dumped 340 chests of English tea into the Boston harbour – an event known as ‘The Boston Tea Party’. The effect was dramatic. Parliament closed the port until the company was compensated for its loss. The colony assembly was dissolved. The colony saw this as an infringement of its freedom. In 1775 the first shots were fired. The British response was slow and disorganized, while the rebels swiftly turned their militias into a citizen army. On 4 July 1776 the colonies issued their Declaration of Independence, establishing themselves as a state independent of Great Britain. The main retaliatory campaign of 1777 ended in disaster. In 1781 the British troops were again defeated. A year later the king had to accept North’s resignation. In 1783 peace was finally made with what had become the United States.

62

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

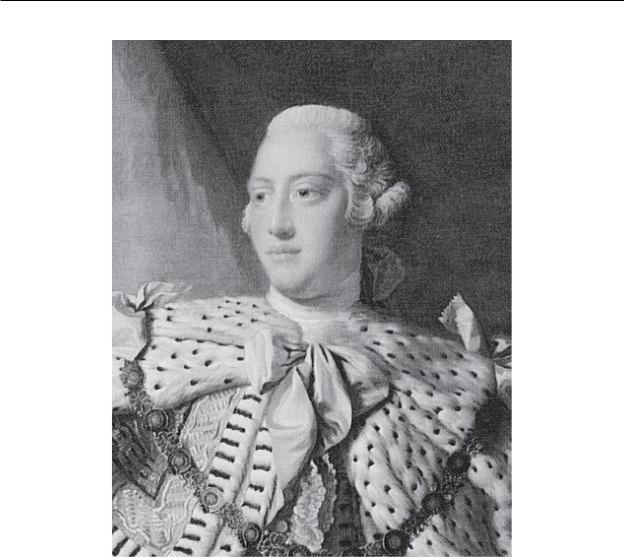

George III

This loss of war and the colonies was a shock for the governing classes. At one blow the First British Empire had been lost. The British also found themselves without allies. Defeat abroad forced the downfall of the personal rule of George III. There were demands for reform of the corrupt parliamentary system.

The fall of Lord North brought a reversion to the political chaos like the one in the 1760s when one ministry succeeded another. There were two rival groups of Whigs: one led by Charles James Fox, the other by William Pitt the Younger. Both had a new political vision to take the country forward after the disaster of the American war, but they were bitter rivals. George III was by that time a highly skilled politician, he favoured Pitt and when Fox won over the majority in the Commons, he plotted his downfall. In the spring of 1784 a general election was held, which gave Pitt a large majority at the expense of Fox and his followers. Thus Pitt entered office and, except for one brief period, was to remain Prime Minister for twenty years until his death in 1806. Pitt was a pragmatist by nature, a brilliant organizer and administrator, who moved with the times and became a symbol of British traditions and virtues. George III came to rely on Pitt much as he had relied on North, the difference being that this time the Prime Minister actually deserved his fullest confidence. Enjoying the support of the king and Parliament, Pitt stabilized the country in 3 years. He carried through reforms of the civil service and government finance, beginning to abolish, for example, the old system of fees in favour of properly salaried posts. Under Pitt the powers of the Prime Minister expanded. A threat to his premiership came in 1787-88 when the

63

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

temporary insanity of George III made a regency appear necessary. Pitt, who knew that the Prince of Wales favoured Fox, delayed the transfer of power as long as he could, until the king finally regained his sanity and the threat was removed.

At first William Pitt stood for progressive reform of the British political system, but the movement to reform was diverted by a more immediate crisis, the menace of revolutionary France, which turned the Prime Minister into a war leader and a conservative eager to preserve the existing system. In July 1789 the Parisian mob stormed the Bastille that embodied the ancien rйgime in France. This event was to be the opening scene of the French revolution, a cataclysm whose consequences were to engulf the whole of Western Europe. It was to divide the Whig party. Pitt drew into his government Whigs who defended the tradition of aristocratic government which they saw under threat, thus forming a conservative alliance (Tory in principle and personnel). Fox and his supporters at first welcomed the revolution, opposed any war against France and supported reform. Later, however, this early enthusiasm was dampened by the revolutionary excesses. The general reaction in England to the revolution was one of utter horror. The aristocratic and propertied classes saw everything they embodied under attack. In 1793 France declared war on Britain and Holland. As the war progressed, the full meaning of this challenge to the British ruling йlite was realized and the war took on the character of a crusade for self-preservation. There was a sharp move in a conservative direction. By 1795 all the radical movements that had sprung up in response to the revolution had been easily suppressed and driven underground.

The war lasted long, embracing Europe, Asia, Africa and North and South America. England was seriously threatened with invasion several times. The British gradually changed their military structure, evolving from an army made up of paid professionals and mercenaries to one which drew into its ranks men of all classes, from all parts of the country. In 1789 the British army numbered just 40,000 men, by 1814 – 250,000. Britain had two main heroes in this war. The first was Horatio Nelson, who commanded the British fleet and defeated Napoleon several times, his last and most victorious battle being the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805), where he was fatally wounded, but the main body of the French and Spanish fleet was destroyed, so that Napoleon could no longer invade Britain. The second one was Arthur Wellesley, made the Duke of Wellington for his victory over the French in 1809. On 18 June 1815 the final battle of the war was fought at Waterloo in present-day Belgium. Napoleon was routed by Wellington. The diplomacy carried out at Vienna was to settle the map of Europe for forty years. Britain played the dominant part through Lord Castlereagh. His aim was a Europe in which France would in no way be humiliated, but the territorial integrity of all the nations would be respected and stability achieved through a careful balance of forces. The British acquisitions were seemingly small, but important for her trade: Malta, Guiana, Tobago, the Cape of Good Hope, Singapore and Malaya. Thus the Second British Empire began in 1815, which now included a new continent – Australia. Britain was the only country to emerge from the war with all her institutions intact. Elsewhere thrones had fallen and a centuriesold order of things had been done away with. Not for nothing was a national anthem ‘God Save the King’ officially adopted in1800. Yet, the country and the ruling classes were different in 1815 from what they had been in 1793.

64

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

George IV

The war with France was a great watershed into the 19th century; it started changes that finally altered the nature of the monarchy and the ruling йlite. They were transformed in response first to the trauma of the American defeat, and then even more to the fear of revolution in their own country. As far as the monarchy was concerned the scene had already been set by George III and his family, who were models of domestic propriety. The king’s relapses into madness (permanent after 1810) only increased the nation’s respect for the man called ‘Farmer George’ and regarded as the father of his people. His popularity was further increased by the decadence of his son, later (from 1810 till 1820) to be Prince Regent and George IV. Victories in the war were celebrated with festivities which focused on the Crown as a symbol of national unity. These were no longer confined to the court but were organized throughout the country. George’s 50th anniversary of accession in 1810 was celebrated throughout the Empire. If the king played the role of the country’s first citizen, his queen, Charlotte, was presented as a pattern for womankind. When George III died in 1820 there was national mourning. While the monarchy now came to embody virtue and patriotism, the ruling йlite underwent an even greater change. Writers in England had already begun to question the rights of an йlite to exercise political power based purely on birth and property. During the thirty years that followed 1780 the landed classes were to transform themselves into people deserving respect from below. The 1770s were now seen as an age of decadence, gross extravagance, gambling and sexual depravity. The new philosophy was that wealth and rank entailed duty, both in terms of public service and private morality. Those who offended the new puritan ethic sought exile abroad.

65

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

The upper classes were perceived as owing their status not only to birth and wealth but even more to their industry in the service of others and morality at home, examples for the lower classes to follow.

In 1815 the British establishment was wealthier, more powerful and more influential than ever before. But with the war now over all kinds of other problems arose on the agenda, which the long struggle against France had postponed. Many of these problems were the consequence of the Industrial Revolution Britain was undergoing during the same years. Its impact was to dominate the new century. Also, the transition from war to peace proved very difficult. The war years had left Britain with a number of restrictions and fear of revolution that made the Tory government hostile to all demands of reform, while the people expected some rewards and several specific reforms for the sacrifices they had made in the struggle with Napoleon.

When the war was over 300,000 soldiers and sailors suddenly flooded onto the job market, bringing mass unemployment. There was trade depression, heavy taxation and bad harvest. The five years after 1815 were to bring Britain closer to revolution from below than any other period in her history. The artisans and workers demanded a reform of Parliament, universal male suffrage, lower taxation and relief from poverty. Caricaturists mercilessly ridiculed what they saw as an extravagant corrupt ruling class led by a man whose decadence was a return to the previous century, the Prince Regent. Yet, no revolution occurred. The radical groups were diverse and divided, but, more significantly, 1820 saw a sharp upward turn in the economy, which was to last for most of the decade. The idea of reform, however, was on the agenda, awaiting its moment.

By 1815 the parliamentary system, which went back to the Middle Ages, had become a gigantic anomaly, no longer reflecting the realities of a quickly changing society. There were 658 MPs in the Commons, but how they were elected and who they represented was to come under increasing fire. There was, for example, no independent representation of the new commercial and industrial centers such as Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds and Sheffield. In sharp contrast there were so called rotten boroughs where few people lived who were open to bribery or influence. One of the most notorious was the long-abandoned medieval borough of Old Sarum where seven electors returned 2 MPs. Freemen often cast their vote in deference to the wishes of the local landowner or else he withdrew his favours. As a result, Parliament remained one large interconnected family.

The 1830s opened with a severe economic crisis which precipitated industrial unrest and uprisings in the countryside. There was a revolution in France again. Radicalism re-emerged. In April 1831 a National Union of the Working Classes was formed, and political unions began to be founded in all the major industrial and commercial centers. In 1830 the unpopular George IV, who had been opposed to constitutional reform of any kind, died to be succeeded by his younger brother. The new king, William IV (1830–1837), was genial and conscientious and, unlike George IV, sympathetic to parliamentary reform. The general election was held in July 1830 and the Wellington government was returned to power. Wellington’s speech at the opening of the new Parliament was in effect a defense of the status quo and caused such a violent reaction that he was forced to resign. The king found that he had only one choice – to turn to a Whig, Earl Grey, who would accept office on one condition – parliamentary reform. Grey understood that the days of aristocratic government could only be prolonged by major reform. In order to reinforce the йlite, it was necessary not only to strengthen the landed interest in the counties, but also give greater weight to the new industrial and commercial middle classes. The Reform Bill was drafted and presented to the House in March 1831, but the Lords dominated by the Tories rejected it in October. Grey resigned in May 1832, William turned the Wellington to form a cabinet, but he failed, and the king called upon Grey again. The latter came back with one condition – if the Lords failed to pass the Bill the king would create enough new peers to outvote the opposition. The Lords gave in and on 7 June the Great Reform Act received the royal assent. The achievement was remarkable, a new parliament emerged. The

66

А. Г. Минченков. «Glimpses of Britain. Учебное пособие»

significance of the Act was only revealed in the retrospect, as the political calm of the Victorian age unfolded in sharp contrast to the turbulence on the continent.

What did the Act do? There was in fact never any question of universal male suffrage. The vote was for those regarded as capable of exercising it, a privilege bestowed upon men who had a vested interest in the stability of the state. That vested interest was embodied in property. In the counties the right to vote was limited to the owners or lessees of land. In towns, the vote was given to all whose houses were valued for rates at 10 pounds p.a., which brought in shopkeepers. In England and Wales this gave vote to one in every five.

The Act also led to the redistribution of seats. Boroughs with less than 2,000 voters lost their MP altogether, those with between 2,000 to 4,000 voters now returned one MP instead of two. The seats thus gained were then redistributed. Twenty-two seats were given to towns previously unrepresented; sixty-five additional seats were given to English counties, eight to Scotland and five to Ireland. Still, 70 seats remained in the control of aristocratic patrons.

There was, however, no change in the type of person who became an MP. The landed interest remained secure, for in order to stand for Parliament there was a Ј300 property qualification for a borough MP and Ј600 for a county MP. The job was to remain unpaid until 1911. Thus rank and property was consolidated and the middle classes, who had flirted with working class radicalism, were firmly tied to the aristocrats. Their instincts anyway were conservative, they had achieved what they most wanted, recognition. The House of Commons now received a much higher status, for in the final stages the Lords had been forced to submit to them. The working classes emerged empty-handed. Thus the 1832 Act effected a new polarity in the country; it divided the nation right down the middle between those who had property and political rights and those who had neither.

67