Encyclopedia of SociologyVol._3

.pdf

MARRIAGE

the mid-30s), varied duration of childbearing (few versus many years), varied number of children (small family versus large), and the ways in which consumer decisions change over the course of marriage (Aldous 1990).

CONCLUSION

If the vitality of marriage is measured by the extent to which men and women enter marriage, then some pessimism about its future is warranted. Marriage rates are currently lower than during the early depression year 1931 (Statistical Abstracts 1998, 1938)—which was the lowest in our nation’s recent history (Sweet and Bumpass 1987). One conclusion that might be drawn from reading the accumulated literature on marriage, especially the writings that discuss the inequities of men and women within marriage, the increasing incidence of marital dissolution, cohabitation as a substitute for marriage, and the postponement of marriage, is that the institution is in serious trouble. These changes have been interpreted as occurring as part of a larger societal shift in values and orientations (Glick 1989) that leans toward valuing adults over children and individualism over familism (Glenn 1987; White 1987; see also the entire December 1987 issue of Journal of Family Issues, which is devoted to the state of the American family). Supporting this perspective are the data on increased marital happiness among childless couples and lower birth rates among married couples.

Yet every era has had those who wrote of the vulnerability of marriage and the family. For example, earlier in this century Edward Alsworth Ross wrote, ‘‘we find the family now less stable than it has been at any time since the beginning of the Christian era’’ (1920, p. 586). Is every era judged to be worse than previous ones when social institutions are scrutinized? More optimistic scholars look at the declining first-marriage rate and interpret it as a ‘‘deferral syndrome’’ rather than an outright rejection of the institution (Glick 1989). This is because, in spite of declines in the overall rate, the historical 8 percent to 10 percent of never-married people in the population has remained constant: Almost 90 percent of all women

in the United States eventually marry at least once in their lifetimes. Also, projections that about twothirds of all first marriages in the United States will end in divorce (Martin and Bumpass 1989) do not deter people from marrying. In spite of the high divorce rate, an increased tolerance for singleness as a way of life, and a growing acceptance of cohabitation, the majority of Americans continue to marry. Marriage is still seen as a source of personal happiness (Kilbourne et al. 1990).

More fundamentally, marriage rates and the dynamics of marital relationships tend to reflect conditions in the larger society. What appears clear, at least for Americans, is that they turn to marriage as a source of sustenance and support in a society where, collectively, citizens seem to have abrogated responsibility for the care and nurturance of each other. Perhaps it is not surprising that divorce rates are high, given the demands and expectations placed on modern marriages.

(SEE ALSO: Alternative Life-Styles; Courtship; Family Roles;

Heterosexual Behavior Patterns; Intermarriage; Marital Adjustment; Remarriage; Sexual Behavior and Marriage)

REFERENCES

Adams, Bert N. 1988 ‘‘Fifty Years of Family Research: What Does It Mean?’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 50:5–17.

Aldous, Joan 1990 ‘‘Family Development and the Life Course: Two Perspectives on Family Change.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 52:571–583.

——— 1996 Family Careers: A Rethinking. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Baca Zinn, Maxine, and D. Stanley Eitzen 1990 Diversity in Families, 2nd ed. New York: Harper & Row.

Barich, Rachel Roseman, and Denise D. Bielby 1996 ‘‘Rethinking Marriage: Change and Stability in Expectations, 1967–1994.’’ Journal of Family Issues 17:139–169.

Barry, W. A. 1970 ‘‘Marriage Research and Conflict: An Integrative Review.’’ Psychological Bulletin 73:41–54.

Belsky, Jay, and Michael Rovine 1990 ‘‘Patterns of Marital Change across the Transition to Parenthood: Pregnancy to Three Years Postpartum.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 52:5–19.

1738

MARRIAGE

Benin, Mary H., and Joan Agostinelli 1988 ‘‘Husbands’ and Wives’ Satisfaction with the Division of Labor.’’

Journal of Marriage and the Family 50:349–361.

Berardo, Felix M. 1990 ‘‘Trends and Directions in Family Research in the 1980s.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 52:809–817.

Fincham, Frank D., and Thomas N. Bradbury 1987 ‘‘The Assessment of Marital Quality: A Reevaluation.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 49:797–809.

Fitzpatrick, Mary Anne 1988 ‘‘Approaches to Marital Interaction.’’ In P. Noller and M. A. Fitzpatrick, eds.,

Perspectives on Marital Interaction. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Bernard, Jessie 1972 The Future of Marriage. New

York: Bantam.

——— 1982 The Future of Marriage. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Blaisure, Karen, and Katherine R. Allen 1995 ‘‘Feminists and the Ideology and Practice of Marital Equality.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 57:5–19.

Bloom, Bernard L., Robert L. Niles, and Anna M. Tatacher 1985 ‘‘Sources of Marital Dissatisfaction among Newly Separated Persons.’’ Journal of Family Issues 6:359–373.

Burleson, Brant R., and Wayne H. Denton 1997 ‘‘The Relationship between Communication Skills and Marital Satisfaction: Some Moderating Effects.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 59:884–902.

Call, Vaughn, Susan Sprecher, and Pepper Schwartz 1995 ‘‘The Incidence and Frequency of Marital Sex in a National Sample.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 57:639–652.

Coltrane, Scott, and Masako Ishii-Kuntz 1992 ‘‘Men’s Housework: A Life Course Perspective.’’ Journal of Marriage and Family 54:43–57.

Cowen, Phillip, and C. Cowen 1989 ‘‘Changes in Marriage during the Transition to Parenthood: Must We Blame the Baby?’’ In G. Michaels and W. Goldberg, eds., The Transition to Parenthood: Current Theory and Research. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, Kingsley 1949 Human Society. New York: Macmillan.

Demo, David H., and Alan C. Acock 1993 ‘‘Family Diversity and the Division of Domestic Labor: How Much Have Things Really Changed?’’ Family Relations 42:323–331.

Durkheim, Emile 1897 Le Suicide. Paris: F. Alcan.

Duvall, Evelyn M., and Reuben Hill 1948 ‘‘Report of the Committee on the Dynamics of Family Interaction.’’ Paper delivered at the National Conference on Family Life, Washington.

Eggebeen, David J., and Adam Davey 1998 ‘‘Do Safety Nets Work? The Role of Anticipated Help in Times of Need.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 60:939–950.

Glenn, Norval D. 1987 ‘‘Tentatively Concerned View of American Marriage.’’ Journal of Family Issues 8:350–354.

——— 1991 ‘‘Qualitative Research on Marital Quality in the 1980s: A Critical Review.’’ In A. Booth, ed.,

Contemporary Families: Looking Forward, Looking Back. Minneapolis, Minn.: National Council on Family Relations.

———, and Sara McLanahan 1982 ‘‘Children and Marital Unhappiness: A Further Specification of the Relationship.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 44:63–72.

Glick, Paul C. 1989 ‘‘The Family Life Cycle and Social Change.’’ Family Relations 38:123–129.

Goode, William J. 1956 After Divorce. New York: Free Press.

Gottman, John Mordechai 1994 What Predicts Divorce? The Relationship between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Holman, Thomas B., and Gregory W. Brock 1986 ‘‘Implications for Therapy in the Study of Communication and Marital Quality.’’ Family Perspectives 20:85–94.

Infante, D. A. 1989 ‘‘Test of an Argumentative Skill Deficiency Model of Interpersonal Violence.’’ Communication Monographs 56:163–177.

Ishii-Kuntz, Masako, and Marilyn Ihinger-Tallman 1991 ‘‘The Subjective Well-Being of Parents.’’ Journal of Family Issues 12:58–68.

Ishii-Kuntz, Masako, and Scott Coltrane 1992 ‘‘Remarriage, Stepparenting, and Household Labor.’’ Journal of Family Issues 13:215–233.

Johnson, Michael P., John P. Caughlin, and Ted L. Huston 1999 ‘‘The Tripartite Nature of Marital Commitment: Personal, Moral, and Structural Reasons to Stay Married.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

61:160–177.

Kilbourne, Barbara S., Frank Howell, and Paula England 1990 ‘‘Measurement Model for Subjective Marital Solidarity: Invariance across Time, Gender and Life Cycle Stage.’’ Social Science Research 19:62–81.

Kitson, Gay C. 1992 Portrait of Divorce: Adjustment to Marital Breakdown. New York: Guilford Press.

———, and Marvin B. Sussman 1982 ‘‘Marital Complaints, Demographic Characteristics and Symptoms of Mental Distress in Divorce.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 44:87–102.

1739

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

Komarovsky, Mirra 1962 Blue Collar Marriage. New York:

Vintage.

Larson, Jeffrey H. 1988 ‘‘The Marriage Quiz: College Students’ Beliefs in Selected Myths about Marriage.’’

Family Relations 37:3–11.

Lasch, Christopher 1977 Haven in a Heartless World. New York: Basic.

Lee, Gary 1982 Family Structure and Interaction: A Comparative Analysis, 2nd ed., rev. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Levinger, George 1996 ‘‘Sources of Marital Dissatisfaction among Applicants for Divorce.’’ American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 36:803–807.

Martin, Teresa C., and Larry L. Bumpass 1989 ‘‘Recent Trends in Marital Disruption.’’ Demography 26:37–51.

McHale, Susan M., and Ted L. Huston 1985 ‘‘Men and Women as Parents: Sex Role Orientations, Employment, and Parental Roles.’’ Child Development 55:1349–1361.

McLanahan, Sara, and J. Adams 1989 ‘‘The Effects of Children on Adults’ Psychological Well-Being. Social Forces 68:124–146.

Montgomery, Rhonda J. 1992 ‘‘Gender Differences in Patterns of Child-Parent Caregiving Relationships.’’ In J. W. Dwyer and R. T. Coward, eds., Gender, Families, and Elder Care. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage.

Noller, Patricia, and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick 1990 ‘‘Marital Communication in the Eighties.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 52:832–843.

O’Donohue, William, and Julie L. Crouch 1996 ‘‘Marital Therapy and Gender-Linked Factors in Communication.’’ Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 22:87–101.

Okun, B. F. 1991 Effective Helping, Interviewing, and

Counseling Techniques, 13th ed. Monterey, Calif.:

Brooks/Cole.

Olsen, David H., D. Sprenkle, and C. Russell 1979 ‘‘Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Systems I: Cohesion and Adaptability Dimensions, Family Types and Clinical Applications.’’ Family Process 18:3–28.

Popenoe, David 1993 ‘‘American Family Decline, 1960– 1990: A Review and Appraisal.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 55:527–555.

Presser, H. B. 1994 ‘‘Employment Schedules among Dual-Earner Spouses and the Division of Household Labor by Gender.’’ American Sociological Review

59:348–364.

Reiss, Ira L., and Gary Lee 1988 Family Systems in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Rosenthal, Carolyn 1985 ‘‘Kinkeeping in the Familial Division of Labor.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

47:965–974.

Ross, Edward Alsworth 1920 The Principles of Sociology. New York: Century.

Rubin, Lillian 1976 Worlds of Pain: Life in the Working Class Family. New York: Basic.

Ruble, Diane, A. Fleming, L. Hackel, and C. Stangor 1988 ‘‘Changes in the Marital Relationship during the Transition to First-Time Motherhood: Effects of Violated Expectations Concerning the Division of Labor.’’ Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

55:78–87.

Slater, Philip 1963 ‘‘On Social Regression.’’ American Sociological Review 28:339–364.

Statistical Abstracts of the United States 1939 Washington: Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce.

——— 1998 Washington: Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce.

Sweet, James A., and Larry L. Bumpass 1987 American Families and Households. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Thompson, Linda, and Alexis J. Walker 1989 ‘‘Gender in Families: Women and Men in Marriage, Work, and Parenthood.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

51:845–871.

Veroff, Joseph, Richard Kulka, and Elizabeth Douvan 1981 Mental Health in America: Patterns of Help-Seeking from 1957 to 1976. New York: Basic.

White, Lynn K. 1987 ‘‘Freedom versus Constraint: The New Synthesis.’’ Journal of Family Issues 8:468–470.

——— 1990 ‘‘Determinants of Divorce: Review of Research in the Eighties.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 52:904–912.

———, and Alan Booth 1985 ‘‘The Transition to Parenthood and Marital Quality.’’ Journal of Family Issues 6:435–449.

———, and John N. Edwards 1986 ‘‘Children and Marital Happiness: Why the Negative Correlation?’’ Journal of Family Issues 7:131–147.

Whyte, Martin K. 1990 Dating, Mating, and Marriage. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

MARILYN IHINGER-TALLMAN

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

Marriage and divorce rates are measures of the propensity for the population of a given area to become married or divorced during a given year. Some of the rates are quite simple, and others are progressively more refined. The simple ones are

1740

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

called crude rates and are expressed in terms of the number of marriages or divorces per 1,000 persons of all ages in the area at the middle of the year. These are the only marriage and divorce rates available for every state in the United States. They have the weakness of including in the base not only young children but also elderly persons, who are unlikely to marry or become divorced. But the wide fluctuations in crude rates over time are obviously associated with changes in the economic, political, and social climate.

More refined rates will be discussed below, but the following illustrative crude rates of marriage for the United States will demonstrate the readily identifiable consequences of recent historical turning points or periods (NCHS 1990a, 1990b, 1998).

Between 1940 and 1946 the crude marriage rate for the United States went up sharply, from 12.1 per 1,000 to 16.4 per 1,000, or by 36 percent, showing the effects of depressed economic conditions before, and disarmament after, World War II.

Between 1946 and 1956 the rate went down rapidly to 9.5 per 1,000, or by 42 percent, as the baby boom peaked. The unprecedented increase in the number of young children was included in the base of the rate, and this helped to lower the rate.

Between 1956 and 1964 the rate declined farther to 9.0 per 1,000, or by 5 percent, as the baby boom ended and the Vietnam War had begun. Between 1964 and 1972 the rate went up moderately to a peak of 10.9 per 1,000, or by 21 percent, as the Vietnam War ended and many returning war veterans married.

Between 1972 and 1990 the crude marriage rate declined irregularly to 9.8 per 1,000 persons of all ages and on down to 8.9 in 1997. The factors involved are discussed below.

At the time of this writing, vital statistics annual reports present only crude marriage and device rates for the United States and individual states (NCHS 1998). More refined rates were last published for 1987 on some subjects and for 1990 on other subjects.

Refined marriage rates show the propensity to marry for adults who are eligible to marry. They exclude from the base all persons who are too young to marry and may also limit the base to an age range within which most marriages occur. The conventional practice of basing these rates on the number of women rather than all adults has the advantage of making the level of the rates correspond approximately to the number of couples who are marrying. Moreover, the patterns of changes in rates over time are generally the same for men and women.

Changes over time in the tendency for adults to marry are more meaningful and may fluctuate more widely if they are reported in refined rather than crude rates. To illustrate, the crude marriage rate declined between 1972 and 1980 from 10.9 per 1,000 population to 10.6, or by only 3 percent, while the refined rate (marriages per 1,000 women 15 to 44 years old) declined from 141.3 to 102.6, or by 27 percent. A change that appeared to be small when measured crudely turned out to be large when based on a more relevant segment of the population. Persons who want to have others believe that the change was small may cite the crude rates, and persons who want to demonstrate that the marital situation was deteriorating rapidly may cite the refined rates. But persons interested in making a balanced presentation may choose to cite both types of results and explain the differences between them.

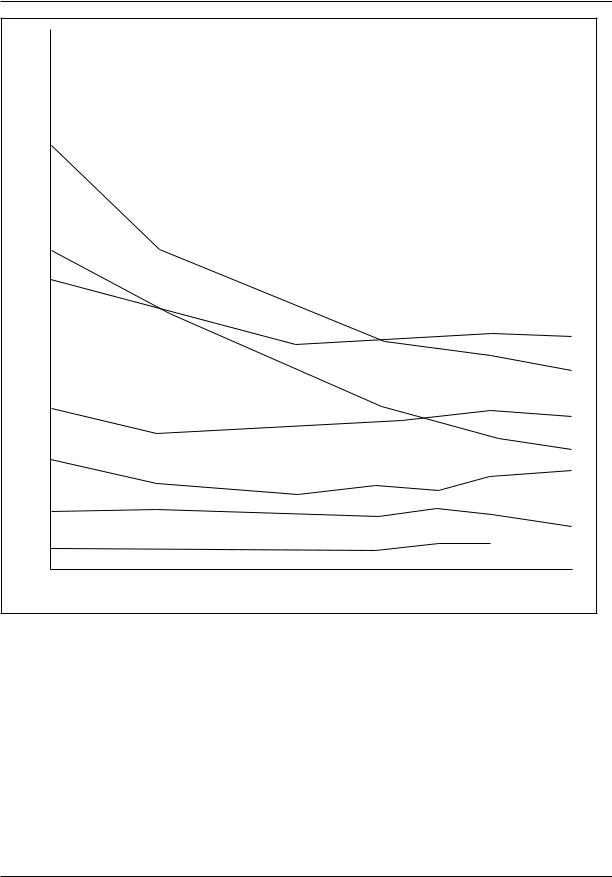

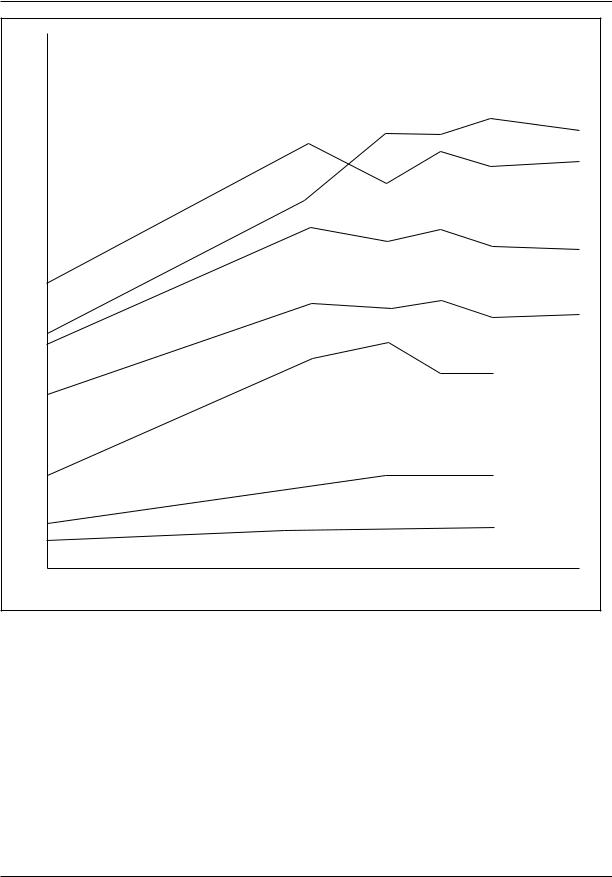

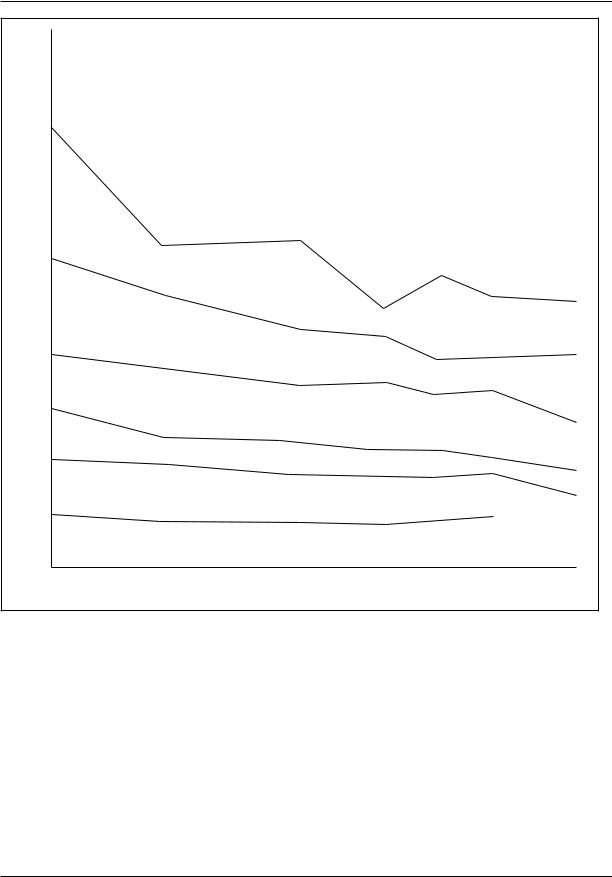

Still greater refinement can be achieved by computing marriage rates according to such key variables as age groups and previous marital status. Examples appear in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 3 for the United States from 1971 to 1990. Table 1 and Figure 1 show first marriage rates by age for the only marital status category of eligible persons, namely, never-married adults (women) 15 years old and over. Figure 2 shows divorce rates by age for married women, and Figure 3 shows remarriage rates by age for divorced women. The low remarriage rates for widows are not shown here but are treated briefly elsewhere in the article. Rates of separation because of marital discord are also not presented here: Separated adults are still legally married and are therefore included in the base of divorce rates.

1741

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

First Marriage Rates per 1,000 Never-Married Women, Divorce Rates per 1,000 Married Women, and Remarriage Rates per 1,000 Divorced Women, by Age: United States, 1970–1990

AGE (YEARS) |

1970a |

1975 |

1980b |

1983 |

1985 |

1987 |

1990 |

|

|

|

|

First Marriage Rate |

|

|

|

15 or over |

93 |

76 |

68 |

64 |

62 |

59 |

58 |

15 to 17 |

36 |

29 |

22 |

16 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

18 to 19 |

150 |

115 |

92 |

73 |

67 |

58 |

53 |

20 to 24 |

198 |

144 |

122 |

107 |

102 |

98 |

93 |

25 to 29 |

131 |

115 |

104 |

105 |

104 |

105 |

109 |

30 to 34 |

75 |

62 |

60 |

61 |

66 |

69 |

71 |

35 to 39 |

48 |

36 |

33 |

38 |

37 |

42 |

47 |

40 to 44 |

27 |

26 |

22 |

22 |

24 |

22 |

20 |

45 to 64 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

8 |

11 |

10 |

NA |

65 or over |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Divorce Rate |

|

|

|

15 or over |

14 |

NA |

20 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

15 to 19 |

27 |

NA |

42 |

48 |

48 |

50 |

49 |

20 to 24 |

33 |

NA |

47 |

43 |

47 |

46 |

46 |

25 to 29 |

26 |

NA |

38 |

36 |

36 |

34 |

37 |

30 to 34 |

19 |

NA |

29 |

28 |

29 |

27 |

28 |

35 to 44 |

11 |

NA |

24 |

25 |

22 |

22 |

NA |

45 to 54 |

5 |

NA |

10 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

NA |

55 to 64 |

3 |

NA |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

NA |

|

|

|

|

Remarriage Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 or over |

133 |

117 |

104 |

92 |

82 |

81 |

76 |

20 to 24 |

420 |

301 |

301 |

240 |

264 |

248 |

252 |

25 to 29 |

277 |

235 |

209 |

204 |

184 |

183 |

200 |

30 to 34 |

196 |

173 |

146 |

145 |

128 |

137 |

138 |

35 to 39 |

147 |

117 |

108 |

99 |

97 |

92 |

93 |

40 to 44 |

98 |

91 |

69 |

67 |

63 |

69 |

69 |

45 to 64 |

47 |

40 |

35 |

31 |

36 |

37 |

NA |

65 or over |

9 |

9 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Table 1

NOTE: aFirst marriage and remarriage rates for 1971. bFirst marriage and remarriage rates for 1979.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics 1990b, 1990c, 1995a, 1995b.

1742

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

|

250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

20 – 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

150 |

18 & 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 – 29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

18 & 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 – 34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

35 – 39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rate |

|

40 – 44 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

First Marriage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

45 – 64 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1971 |

1975 |

1980 |

1983 |

1985 |

1987 |

1990 |

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1

NOTE: First marriage rate per 1,000 never-married women, by age: United States, 1971–1990.

The marriage and divorce rates in Table 1 were based on data from reports published by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). These reports contain information, obtained from central offices, of vital statistics in the states that are in the Marriage Registration Area (MRA) and the Divorce Registration Area (DRA). In 1990 the District of Columbia and all but eight states were in the MRA, while the District of Columbia and

only thirty-one states were in the DRA. Funding for the central offices is determined by each state’s legislature. But for states not in the MRA or DRA, the NCHS requests the numbers of marriages and divorces from local offices where marriage and divorce certificates are issued. The reports on divorce include the small number of annulments and dissolutions of marriage. Bases for the marriage and divorce rates in Table 1 were obtained

1743

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

from special tabulations made by the U.S. Bureau of the Census from Current Population Survey data. These are tabulations of adults in MRA and DRA states and classified by marital status, age, and sex. Because not all the population of the United States is included in the MRA and DRA, the detailed marriage and divorce statistics published by the NCHS constitute approximations of the marital situation in the country as a whole. This article contains much numerical information that was published in one or more of the NCHS reports listed in References.

FIRST MARRIAGE RATES BY AGE

Illustrations of first marriage rates appear in table 1. For the United States, the first marriage rates per 1,000 never-married women 15 years old and over were 93 in 1971 and 58 in 1990. In effect, 9.3 percent of the never-married women in 1971 and 5.8 percent in 1990, became married for the first time. For men the corresponding rates were 68 in 1971 and 47 in 1990.

First marriage rates tend to decline with age, and the rates for most of the age groups shown in Table 1 were declining over time. The rates for the age groups under 20 years of age were among the highest, but they dropped so sharply that they were only about one-third as high in 1990 as they had been in 1971. At the oldest ages, the change appears to have been slight. Obviously, the propensity to marry was falling far more abruptly among the young than among the older singles, probably in reaction to the suddenly changing cultural climate.

The generally downward trend in the marriage rate for each young age group was especially rapid during the early 1970s. By 1975, the veterans of the Vietnam War had already entered delayed marriages, and the upsurge in cohabitation outside marriage was only beginning to depress the first marriage rate. During the 1980s the slight upturn in the first marriage rate for women over 30 years of age probably reflected an increase in marriages among women who had delayed marrying for the purposes of obtaining a higher education and becoming established in the workplace.

Research has produced evidence that women who marry for the first time after they reach their thirties are more likely to have stable marriages than those who marry in their twenties (Norton and Moorman 1987). Although first marriage rates among adults in their forties are relatively low, they are by no means negligible.

As first marriage rates declined between the mid-1960s and the late 1980s, the median age at first marriage rose at an unprecedented pace over this short period of time. According to vital statistics, the median age at first marriage for women went up from 20.3 years in 1963 to 24.0 in 1990, for men it went up from 22.5 years to 25.9 years. As age at first marriage increased, the distribution of ages at first marriage also increased (Wilson and London 1987).

One of the consequences of the great delay of first marriage has been a very sharp rise in premarital pregnancy. Only 5 percent of births in 1960 occurred to unmarried mothers, but this increased to 24 percent in 1987 and to 32 percent in 1996. Research by Bumpass and McLanahan (1989) showed that one-half of nonmarital births during the late 1980s were first births, and about one-third occurred to teenagers. Moreover, about one-tenth of brides were pregnant at first marriage. Thus, about one-third of the first births during the late 1980s were conceived before marriage.

As the first marriage rate declined, the proportion of all marriages that were primary marriages (first for bride and groom) also declined. In 1970, two-thirds (68 percent) were primary marriages, but by 1987 the proportion was barely over one-half (54 percent). Meantime, marriages of divorced brides to divorced grooms nearly doubled, from 11 percent to 19 percent, while marriages of widows to widowers went down from 2 percent to 1 percent.

Men and women, regardless of previous marital status, tend to marry someone whose age is similar to their own. But men who enter first marriage when they are older than the average age of men at marriage have a reasonable likelihood of marrying a woman who has been divorced.

Procedures have been developed for projecting the proportion of adults of a certain age who

1744

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

|

60 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 – 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 |

15 – 19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 – 29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

30 – 34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

10 |

35 – 44 |

|

|

|

|

|

Rate |

|

45 – 54 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

55 – 64 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Divorce |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

1970 |

1980 |

1983 |

1985 |

1987 |

1990 |

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2

NOTE: Divorce rate per 1,000 married women, by age: United States, 1970–1990.

are likely to enter first marriage sometime during their lives. This measure is, in effect, ‘‘a lifetime first marriage rate.’’ One of these procedures was used by Schoen and colleagues (1985) to find that about 94 percent of men who were born in the years 1948 to 1950 and who survived to age 15 were expected to marry eventually; for women, it was 95 percent. Their projections for those born in 1980 were significantly lower, 89 percent for men

and 91 percent for women. Despite the implied decline, a level of nine-tenths of the young adults deciding to marry at least once is still high by world standards.

DIVORCE RATES BY AGE

As indicated above, crude divorce rates are the only rates available annually for the United States and

1745

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

|

500 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

20 – 24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

400 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

300 |

25 – 29 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

30 – 34 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

35 – 39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

40 – 44 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rate |

|

45 – 64 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Remarriage |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1971 |

1975 |

1980 |

1983 |

1985 |

1987 |

1990 |

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 3

NOTE: Remarriage rate per 1,000 divorced women, by age: United States, 1971–1990.

individual states. As recently as 1965, the rate was only 2.5 divorces per 1,000 persons in the United States, but by 1979 the rate reached a peak more than twice that high, 5.3. Then the rate declined gradually until 1997, when it was down to 4.3, the lowest rate since 1973.

The most recent refined divorce rates available include those by age and sex in Table 1 for 1990. The report for that year also presented other

refined divorce statistics on the number of divorces occurring among persons in their first marriage, their second marriage, and their third or subsequent marriage (NCHS 1995b). But the required bases for computing first divorce rates and redivorce rates are not available. During the 1980s, about three-fourths of the divorces were obtained by adults in their first marriage, about one-fifth by

1746

MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE RATES

those in their second marriage, and one-twentieth by those who had been married at least three times.

The divorce rates in Table 1 provide illustrations of the magnitude of the rates for the period 1970 to 1990. The divorce rate per 1,000 married women was 14 in 1970 and 19 in 1990. Corresponding rates for men were the same. The rate reached a peak of 20 in 1980, nearly half again as high as in 1970, and declined slightly to 19 in 1987, a level still well above that in 1970.

The divorce rate for married women rose dramatically in every age group during the 1970s and changed relatively little from then through the 1980s. In January 1973 the Vietnam War ended, and at that time the norms regarding the sanctity of marriage were being revised. The advantages of a permanent marriage were being weighed against the alternatives, including freedom from a seriously unsatisfactory marital bond and the prospect of experimenting with cohabitation outside marriage or living alone without any marital entanglements.

By 1994, one-fourth of divorced persons were cohabiting outside marriage, one-third were living alone, and most of the rest were in single-parent families (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1996).

Married women under 25 years of age have consistently high divorce rates resulting largely from adjustment difficulties associated with early first marriage. Noteworthy in this context is the finding that 30 percent of the women entering a first marriage in 1980 were in their teens, while 40 percent of those obtaining a divorce had entered their marriage while teenagers.

More divorces during the 1980s were occurring to married adults 25 to 34 years of age than to those in any other ten-year age group. A related study by Norton and Moorman (1987) concluded that women in their late thirties in 1985 were likely to have higher lifetime divorce rates (55 percent) than those either ten years older or ten years younger. This cohort was born during the vanguard of the baby boom and became the trend setter for higher divorce rates. The lower rate for those ten years younger may reflect their concern caused by the adjustment problems of their older divorced siblings or friends.

Married women over 45 years of age have quite low divorce rates. Most of their marriages

must still be reasonably satisfactory, or not sufficiently unsatisfactory to persuade them to face the disadvantages that are often associated with becoming divorced. Yet, the forces that raised the divorce rate for younger women greatly after 1970 also made the small rate for the older women increase by one-fourth during the 1970s and remain at about the same level through the 1980s.

The median duration of marriage before divorce has been seven years for several decades. This finding is not proof of a seven-year itch. In fact, the median varies widely according to previous marital status from eight years for first marriages to six years for second marriages and four years for third and subsequent marriages. The number of divorces reaches a peak during the third year of marriage and declines during each succeeding year of marriage.

Among separating couples, the wife usually files the petition for divorce. However, between 1975 and 1987, the proportion of husband petitioners increased from 29.4 percent to 32.7 percent, and the small proportion of divorces in which both the husband and the wife were petitioners more than doubled, from 2.8 percent to 6.5 percent. These changes occurred while the feminist movement was becoming increasingly diffused and the birthrate was declining, with the consequence that only about one-half (52 percent) of the divorces in 1987 involved children under 18 years of age and one-fourth (29 percent) involved only one child. It is not surprising that nine-tenths of children under 18 living with a divorced parent live with their mother, far more often in families with smaller average incomes than those living with divorced fathers.

Although only about one-tenth of the adults in the United States in 1988 were divorced (7.4 percent) or separated (2.4 percent), the lifetime experience of married persons with these types of marital disruption is far greater. Based on adjustments for underreporting of divorce data from the Current Population Survey and for underrepresentation of divorce from vital statistics in the MRA, Martin and Bumpass (1989) have concluded that two-thirds of current marriages are likely to end in separation or divorce.

1747