Encyclopedia of SociologyVol._3

.pdf

MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

‘‘How often do you and your partner quarrel?’’ and ‘‘How often do you discuss or have you considered divorce, separation, or terminating your relationship?’’ The dyadic cohesion subscale is made up of five questions, ‘‘Do you and your mate engage in outside interests together?’’ and ‘‘How often would you say the following events occur between you and your mate?—have a stimulating exchange of ideas, laugh together, calmly discuss something, or work together on a project.’’ The dyadic consensus subscale is based on thirteen questions on ‘‘the extent of agreement or disagreement between you and your partner.’’ Items range from handling family finances, religious matters, and philosophy of life, to household tasks. Finally, the affectional expression subscale is composed of four questions related to affection and sex, two of which are agreement questions on demonstration of affection and sex relations.

All the above measures have been criticized as lacking a criterion against which the individual items are validated (Norton 1983; Fincham and Bradburn 1987). Some scholars have argued that only global and evaluative items, rather than con- tent-specific and descriptive ones, should be included in marital adjustment or quality measures, because the conceptual domain of the latter is not clear. What constitutes a well-adjusted marriage may differ from one couple to another as well as cross-culturally and historically. Whether or not spouses kiss each other every day, for example, may be an indicator of a well-adjusted marriage in the contemporary United States but not in some other countries. Thus, marital adjustment or quality should be measured by the spouses’ evaluation of the marriage as a whole rather than by its specific components. Instead of ‘‘How often do you and your husband (wife) agree on religious matters?’’ (a content-specific description), it is argued that such questions as ‘‘All things considered, how satisfied are you with your marriage?’’ and ‘‘How satisfied are you with your husband (wife) as a spouse?’’ (a global evaluation) should be used. By the same reasoning, the Kansas Marital Satisfaction (KMS) scale has been proposed. This test includes only three questions: ‘‘How satisfied are you with your (a) marriage: (b) husband (wife)

as a spouse: and (c) relationship with your husband (wife)?’’ (Schumm et al. 1986).

Traditional indexes also have been criticized for their lack of theoretical basis and the imposition of what constitutes a ‘‘successful marriage.’’ On the basis of exchange theory, Ronald Sabatelli (1984) developed the Marital Comparison Level Index (MCLI), which measures marital satisfaction by the degree to which respondents feel that the outcomes derived from their marriages compare with their expectations. Thirty-six items pertaining to such aspects of marriage as affection, commitment, fairness, and agreement were originally included, and thirty-two items were retained in the final measure. Because this measure is embedded in the tradition of exchange theory, it has strength in its validity.

PREDICTING MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

How is the marital adjustment of a given couple predicted? According to Lewis and Spanier’s (1979) comprehensive work, three major factors predict marital quality; social and personal resources, satisfaction with lifestyle, and rewards from spousal interaction.

In general, the more social and personal resources a husband and wife have, the better adjusted their marriage is. Material and nonmaterial properties of the spouses enhance their marital adjustment. Examples include emotional and physical health, socioeconomic resources such as education and social class, personal resources such as interpersonal skills and positive self-concepts, and knowledge they had of each other before getting married. It was also found that good relationships with and support from parents, friends, and significant others contribute to a well-adjusted marriage. Findings that spouses with similar racial, religious, or socioeconomic backgrounds are better adjusted to their marriages are synthesized by this general proposition.

The second major factor in predicting marital adjustment is satisfaction with lifestyle. It has been found that material resources such as family income positively affect both spouses’ marital adjustment. Both the husband’s and the wife’s satisfaction with their jobs enhances better-adjusted

1728

MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

marriages. Furthermore, the husband’s satisfaction with his wife’s work status also affects marital adjustment. The wife’s employment itself has been found both instrumental and detrimental to the husbands’ marital satisfaction (Fendrich 1984). This is because the effect of the wife’s employment is mediated by both spouses’ attitudes toward her employment. When the wife is in the labor force, and her husband supports it, marital adjustment can be enhanced. On the other hand, if the wife is unwilling to be employed, or is employed against her husband’s wishes, this can negatively affect their marital adjustment. Marital adjustment is also affected by the spouses’ satisfaction with their household composition, by how well the couple is embedded in the community, and the respondent’s health (Booth and Johnson 1994).

Parents’ marital satisfaction was found to be a function of the presence, density, and ages of children (Rollins and Galligan 1978). Spouses (particularly wives) who had children were less satisfied with their marriages, particularly when many children were born soon after marriage at short intervals. The generally negative effects of children on marital satisfaction and marital adjustment could be synthesized under this more general proposition about satisfaction with lifestyle.

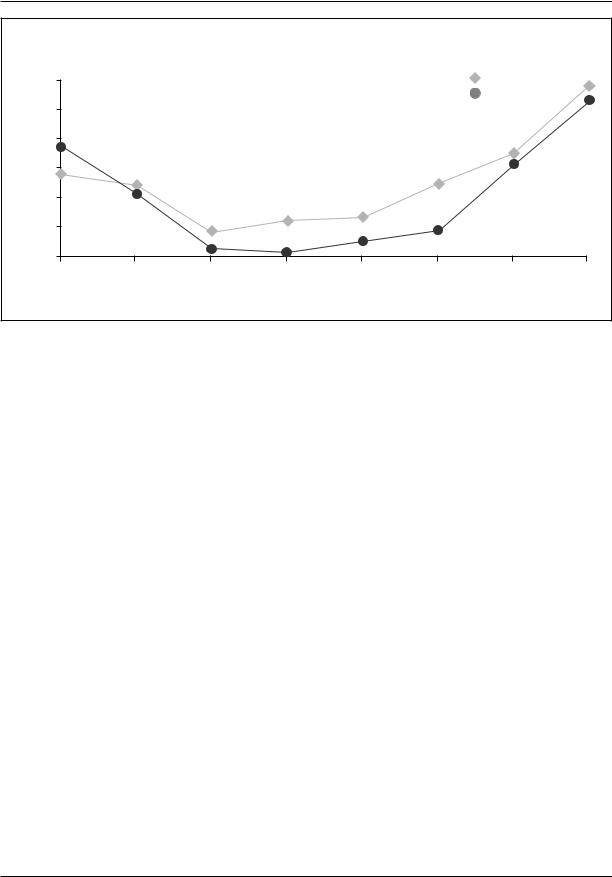

It has been consistently found that marital satisfaction plotted against the couple’s family lifecycle stages forms a U-shaped curve (Rollins and Cannon 1974; Vaillant and Vaillant 1993). Both spouses’ marital satisfaction is quite high right after they marry, hits the lowest point when they have school-age children, and gradually bounces back after all children leave home. To illustrate this pattern, publicly available data from the National Survey of Families and Households (collected in 1987 and 1988) are analyzed here. Figure 1 shows the result. While husbands’ average marital satisfaction hit the lowest point when their oldest child was between 3 and 5 years old, wives satisfaction was lowest when their oldest child was between 6 and 12 years old.

This pattern has been interpreted as a result of role strain or role conflict between the spousal, parental, and work roles of the spouses. Unlike

right after the marriage and the empty-nest stages, having children at home imposes the demand of being a parent in addition to being a husband or wife and a worker. When limited time and energy cause these roles to conflict with each other, the spouses feel strain, which results in poor marital adjustment (Lavee et al. 1996). Along this line of reasoning, Wesley Burr et al. (1979) proposed that marital satisfaction is influenced by the qualities of the individual’s role enactment as a spouse and of the spouse’s role enactment. They argue further, from the symbolic-interactionist perspective, that the relationship between marital role enactment and marital satisfaction is mediated by the importance placed on spousal role expectations.

As seen above, the concept of family life cycle seems to have some explanatory power for marital adjustment. Researchers and theorists have found, however, that family life cycle is multidimensional and conceptually unclear. Once a relationship between a particular stage in the family life cycle and marital adjustment is identified, further variables must be added to explain that relationship—vari- ables such as the wife’s employment status, disposable income, and role strain between spousal and parental roles (Crohan 1996; Schumm and Bugaighis 1986). Furthermore, the proportion of variance in marital adjustment ‘‘explained’’ by the family’s position in its life cycle is small, typically less than 10 percent (Rollins and Cannon 1974). In the case of our analysis above, it is only 3 percent for both husbands and wives. Thus, some scholars conclude that family life cycle has no more explanatory value than does marriage or age cohort (Spanier and Lewis 1980).

The last major factor in predicting marital adjustment is the reward obtained from spousal interaction. On the basis of exchange theory, Lewis and Spanier summarize past findings that ‘‘the greater the rewards from spousal interaction, the greater the marital quality’’ (Lewis and Spanier 1979, p. 282). Rewards from spousal interaction include value consensus; a positive evaluation of oneself by the spouse; and one’s positive regard for things such as the physical, mental, and sexual attractiveness of the spouse. Other rewards from spousal interaction include such aspects of emotional gratification as the expression of affection;

1729

MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

|

Husbands' and Wives' Average Marital Quality Scores by Family Life Cycle Stages1,2,3 |

|

||||||

|

0.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Husbands |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Wives |

|

|

0.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Score |

0.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quality |

0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marital |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Family Life Cycle Stages |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1. Husbands’ and Wives’ Average Marital Quality Scores by Family Life Cycle Stages1,2,3

NOTE: 1. See Sweet, Bumpass, and Call (1988) for the structure and data of the survey. Included in this figure are first-time married couples with at least one child or no child but married for less than 10 years.

2. Family life cycles stages are defined as follows (see Duvall 1977):

Stage 1 (Married Couples): Married for less than 10 years with no children

Stage 2 (Childbearing Families): The oldest child younger than 30 months

Stage 3 (Families with Preschool Children): The oldest child younger than 6

Stage 4 (Families with School Children): The oldest child younger than 13

Stage 5 (Families with Teenagers): The oldest child younger than 20

Stage 6 (Families Launching Young Adults): The oldest child 20 or older

Stage 7 (Middle-Aged Parents): The youngest child 20 or older

Stage 8 (Aging Families): The youngest child 20 or older and one of the spouses is 60 or older

3. Marital quality is measured by three questions: ‘‘Taking things all together, how would you describe your marriage? Very happy (7) to Very unhappy (1).’’ ‘‘Do you feel that your marriage might be in trouble right now? Yes (2) or No (1).’’ ‘‘What do you think the chances are that you and your husband/wife will eventually separate or divorce? Very low (5) to Very high (1).’’ The last two items are rescaled in such a way that the three items are given the same weight and the mean is set to 0. The final score is the average of these three scores.

respect and encouragement between the spouses; love and sexual gratification; and egalitarian relationships. Married couples with effective communication, expressed in self-disclosure, frequent successful communication, and understanding and empathy, are better adjusted to their marriages (Erickson 1993). Complementarity in the spouses’ roles and needs, similarity in personality traits, and sexual compatibility all enhance marital adjustment. Finally, frequent interaction between the spouses leads to a well-adjusted marriage. The lack of spousal conflict or tensions should be added to the list of rewards from spousal interactions.

In this context, it is interesting to compare the average marital quality between men and women (Figure 1). The husbands’ average marital quality is higher than the wives’ except before they have their first child. The wife’s marital quality is initially higher than the husband’s, but it decreases after the arrival of her first baby. After that, it tends to be lower than that of her husband during the entire span of their marriage. Given that women perform most of the child care and household work, the steep decline in the average marital quality for women from Stage 1 to Stage 3 can be interpreted as a result of this burden of household

1730

MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

work and child care. Women’s rewards from marriage are lower than those of men, on the average, and this differential appears as a gender difference in marital adjustment over the family life-cy- cle stages.

Symbolic interactionists also argue that relative deprivation of the spouses affects their marital satisfaction: If, after considering all aspects of the marriage, spouses believe themselves to be as well off as their reference group, they will be satisfied with their marriages. If they think they are better off or worse off than others who are married, they will be more or less satisfied with their marriages, respectively (Burr et al. 1979).

CONSEQUENCES OF MARITAL

ADJUSTMENT: PERSONAL ADJUSTMENT

AND MARITAL STABILITY

It has been widely shown that married persons tend to be better adjusted in their lives than either never-married, separated, divorced, or widowed persons. This seems true not only in the area of psychological adjustments such as depression and general life satisfaction, but also in the area of physical health. Married people are more likely to be healthy and to live longer. Two factors should be considered to account for this relationship. First, psychologically and physically well-adjusted persons are more likely to get married and stay married. Second, the favorable socioeconomic status of married persons may explain some of this relationship. Nevertheless, scholars generally agree that marriage has a positive effect on personal adjustment, in both psychological and physical aspects.

If marriages in general affect personal adjustment in a positive fashion, it is likely that welladjusted marriages lead to well-adjusted lives. Past research shows just this, though the findings should be cautiously interpreted. Some people tend to favorably answer ‘‘adjustment’’ questions, whether the questions are about their marriages, their personal lives in general, or their subjective health. The apparent positive relationship may be spurious. Nevertheless, if the psychological adjustment

is a composite of the adjustments in various aspects of life (i.e., marriage, family, work, health, friendship, etc.), high marital adjustment should lead to high psychological adjustment. In addition, positive effects of well-adjusted marriages on physical health may be accounted for, in part, by psychosomatic aspects of physical health.

This relationship provides an important policy implication of marital adjustment. Well-adjust- ed marriages may reduce health service costs, involving both mental and physical health. This is in addition to the more obvious reduction in social service costs derived from unstable and/or unhappy marriages. Children of divorce who need special care and domestic violence are just two examples through which poorly adjusted marriages become problematic and incur social services expenses.

Does marital adjustment affect the stability of a marriage? Does a better-adjusted marriage last longer than a poorly adjusted one? The answer is generally yes, but this is not always the case. Some well-adjusted marriages end in divorce, and many poorly adjusted marriages endure. As for the latter, John Cuber and Peggy Harroff conducted research on people whose marriages ‘‘lasted ten years or more and who said that they have never seriously considered divorce or separation’’ (1968, p. 43). They claim that not all the spouses in these marriages are happy and that there are five types of long-lasting marriages. In a ‘‘conflict-habituated marriage,’’ the husband and the wife always quarrel. In a ‘‘passive-congenial marriage,’’ the husband and the wife take each other for granted without zest, while ‘‘devitalized marriages’’ started as loving but have degenerated to passive-congen- ial marriages. In a ‘‘vital marriage,’’ spouses enjoy together such things as hobbies, careers, or community services, while in a ‘‘total marriage,’’ spouses do almost everything together. It should be noted that even conflict-habituated or devitalized marriages can last as long as vital or total marriages. For people in passive-congenial marriages, the conception and the reality of marriage are devoid of romance and are different from other people’s.

What then determines the stability of marriage and how the marital adjustment affects it? It

1731

MARITAL ADJUSTMENT

is proposed that although marital adjustment leads to marital stability, two factors intervene; alternative attractions and external pressures to remain married (Lewis and Spanier 1979). People who have both real and perceived alternatives to poorly adjusted marriages—other romantic relationships or successful careers—may choose divorce. A person in a poorly adjusted marriage may remain in it if there is no viable alternative, if a divorce is unaffordable or would bring an intolerable stigma, or if the person is exceptionally tolerant of conflict and disharmony in the marriage. Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that even though marital stability is affected by alternative attractions and external pressures, marital adjustment is the single most important factor in predicting marital stability. Lack of large-scale longitudinal data and adequate statistical technique have hampered scholars’ efforts to establish this link between marital adjustment and stability. Given recent availability of longitudinal and technological development, this area of research holds a high promise.

(SEE ALSO: Divorce; Family Roles; Interpersonal Attraction;

Marriage)

REFERENCES

Bernard, Jessie 1972 The Future of Marriage. New York:

World Publishing.

Booth, Alan, and David R. Johnson 1994 ‘‘Declining Health and Marital Quality.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 56:218–223.

Burgess, Ernest W., and Leonard Cottrell, Jr. 1939

Predicting Success or Failure in Marriage. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Burr, Wesley R., Geoffrey K. Leigh, Randall D. Day, and John Constantine 1979 ‘‘Symbolic Interaction and the Family.’’ In W. Burr, R. Hill, F. I. Nye, and I. Reiss, eds., Contemporary Theories about the Family. New York: Free Press.

Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, and Willard L. Rodgers 1976 The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Crohan, Susan E. 1996 ‘‘Marital Quality and Conflict Across the Transition to Parenthood in African American and White Couples.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 58:933–944.

Cuber, John F., and Peggy B. Harroff 1968 The Significant Americans: A Study of Sexual Behavior among the Affluent. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

Donohue, Kevin C., and Robert G. Ryder 1982 ‘‘A Methodological Note on Marital Satisfaction and Social Variables.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

44:743–747.

Duvall, Evelyn M. 1977 Marriage and Family Development, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Erickson, Rebecca J. 1993 ‘‘Reconceptualizing Family Work: The Effect of Emotion Work on Perception of Marital Quality.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

55:888–900.

Fendrich, Michael 1984 ‘‘Wives’ Employment and Husbands’ Distress: A Meta-Analysis and a Replication.’’

Journal of Marriage and the Family 46:871–879.

Fincham, Frank D., and Thomas N. Bradbury 1987 ‘‘The Assessment of Marital Quality: A Reevaluation.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 49:797–809.

Hamilton, Gilbert V. 1929 A Research in Marriage. New York: A. and C. Boni.

Hawkins, James L. 1968 ‘‘Associations Between Companionship, Hostility, and Marital Satisfaction.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 30:647–650.

Lavee, Yoav, Shlomo Sharlin, and Ruth Katz 1996 ‘‘The Effect of Parenting Stress on Marital Quality: An Integrated Mother-Father Model.’’ Journal of Family Issues 17:114–135.

Lewis, Robert A., and Graham B. Spanier 1979 ‘‘Theorizing about the Quality and Stability of Marriage.’’ In W. Burr, R. Hill, F. I. Nye, and I. Reiss, eds.,

Contemporary Theories About the Family. New York: Free Press.

Lively, Edwin L. 1969 ‘‘Toward Concept Clarification: The Case of Marital Interaction.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 31:108–114.

Locke, Harvey J., and Karl M. Wallace 1959 ‘‘Short Marital-Adjustment and Prediction Tests: Their Reliability and Validity.’’ Marriage and Family Living 21:251–255.

Norton, Robert 1983 ‘‘Measuring Marital Quality: A Critical Look at the Dependent Variable.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 45:141–151.

Rollins, Boyd C., and Kenneth L. Cannon 1974 ‘‘Marital Satisfaction over the Family Life Cycle: A Reevaluation.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 36:271–282.

———, and Richard Galligan 1978 ‘‘The Developing Child and Marital Satisfaction of Parents.’’ In R. M.

1732

MARRIAGE

Lerner and G. B. Spanier, eds., Child Influences on Marital and Family Interaction. New York: Academic Press.

Sabatelli, Ronald M. 1984 ‘‘The Marital Comparison Level Index: A Measure for Assessing Outcomes Relative to Expectations.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 46:651–662.

Schumm, Walter R., and Margaret A. Bugaighis 1986 ‘‘Marital Quality over the Marital Career: Alternative Explanations.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family

48:165–168.

Schumm, Walter R., Lois A. Paff-Bergen, Ruth C. Hatch, Felix C. Obiorah, Janette M. Copeland, Lori D. Meens, and Margaret A. Bugaighis 1986 ‘‘Concurrent and Discriminant Validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 48:381–387.

Spanier, Graham B. 1976 ‘‘Measuring Dyadic Adjustment: New Scales for Assessing the Quality of Marriage and Similar Dyads.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 38:15–28.

———, and Charles L. Cole 1976 ‘‘Toward Clarification and Investigation of Marital Adjustment.’’ International Journal of Sociology and the Family 6:121–146.

Spanier, Graham B., and Robert A. Lewis 1980 ‘‘Marital Quality: A Review of the Seventies.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 42:825–839.

Sweet, James A., Larry L. Bumpass, and Vaughn R. A. Call 1988 A National Survey of Families and Households. Madison: Center for Demography and Ecology, University of Wisconsin.

Trost, Jan E. 1985 ‘‘Abandon Adjustment!’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 47:1072–1073.

Vaillant, Caroline O., and George E. Vaillant 1993 ‘‘Is the U-Curve of Marital Satisfaction an Illusion? A 40Year Study of Marriage.’’ Journal of Marriage and the Family 55:230–239.

YOSHINORI KAMO

MARRIAGE

The current low rates of marriage and remarriage and the high incidence of divorce in the United States are the bases of deep concern about the future of marriage and the family. Some have used these data to argue the demise of the family in

American Society (Popenoe 1993). Others see such changes as normal shifts and adjustments to societal changes (Barich and Bielby 1996). Whatever the forecast, there is no question that the institution of marriage is currently less stable than it has been in previous generations. This article explores the nature of modern marriage and considers some of the reasons for its vulnerability.

Marriage can be conceptualized in three ways: as an institution (a set of patterned, repeated, expected behaviors and relationships that are organized and endure over time); as rite or ritual (whereby the married status is achieved); and as a process (a phenomenon marked by gradual changes that lead to ultimate dissolution through separation, divorce, or death). In the discussion that follows we examine each of these conceptualizations of marriage, giving the greatest attention to marriage as a process.

MARRIAGE AS INSTITUTION

From a societal level of analysis the institution of marriage represents all the behaviors, norms, roles, expectations, and values that are associated with the legal union of a man and woman. It is the institution in society in which a man and woman are joined in a special kind of social and legal dependence to found and maintain a family. For most people, getting married and having children are the principal life events that mark the passage into mature adulthood. Marriage is considered to represent a lifelong commitment by two people to each other and is signified by a contract sanctioned by the state (and for many people, by God). It thus involves legal rights, responsibilities, and duties that are enforced by both secular and sacred laws. As a legal contract ratified by the state, marriage can be dissolved only with state permission.

Marriage is at the center of the kinship system. New spouses are tied inextricably to members of the kin network. The nature of these ties or obligations differs in different cultures. In many societies almost all social relationships are based on or mediated by kin, who may also serve as allies in times of danger, may be responsible for the transference of property, or may be turned to in times

1733

MARRIAGE

of economic hardship (Lee 1982). In the United States, kin responsibilities rarely extend beyond the nuclear family (parents and children). There is the possible exception of caring for elderly parents, where norms seem to be developing (Eggebeen and Davey 1998). There are no normative obligations an individual is expected to fulfill for sisters or brothers, not to mention uncles, aunts, and cousins. Associated with few obligations and responsibilities is greater autonomy and independence from one’s kin.

In most societies the distribution of power in marriage is given through tradition and law to the male—that is, patriarchy is the rule as well as the practice. For many contemporary Americans the ideal is to develop an egalitarian power structure, but a number of underlying conditions discourage attaining this goal. These deterrents include the tendency for males to have greater income; high- er-status jobs; and, until recently, higher educational levels than women. In addition, the tradition that women have primary responsibility for child rearing tends to increase their dependency on males.

Historically, the institution of marriage has fulfilled several unique functions for the larger society. It has served as an economic alliance between two families, as the means for legitimizing sexual relations, and as the basis for legitimizing parenthood and offspring. In present-day America the primary functions of marriage appear to be limited to the legitimization of parenthood (Davis 1949; Reiss and Lee 1988) and the nurturance of family members (Lasch 1977). Recently, standards have changed and sexual relationships outside marriage have become increasingly accepted for unmarried people. Most services that were once performed by members of a family for other members can now be purchased in the marketplace, and other social institutions have taken over roles that once were assigned primarily to the family. Even illegitimacy is not as negatively sanctioned as in the past. The fact that marriage no longer serves all the unique functions it once did is one reason some scholars have questioned the vitality of the institution.

MARRIAGE AS RITE OR RITUAL

Not a great deal of sociological attention has been given to the study of marriage as a rite or ritual that

transfers status. Philip Slater, in a seminal piece published in 1963, discussed the significance of the marriage ceremony as a social mechanism that underscores the dependency of the married couple and links the new spouses to the larger social group. Slater claims that various elements associated with the wedding (e.g., bridal shower, bachelor party) help create the impression that the couple is indebted to their peers and family members who organize these events. He writes,

[F]amily and friends [are] vying with one another in claiming responsibility for having ‘‘brought them together’’ in the first place. This impression of societal initiative is augmented by the fact that the bride’s father ‘‘gives the bride away.’’ The retention of this ancient custom in modern times serves explicitly to deny the possibility that the couple might unite quite on their own. In other words, the marriage ritual is designed to make it appear as if somehow the idea of the dyadic union sprang from the community, and not from the dyad itself. (p. 355)

Slater describes the ways in which rite and ceremony focus attention on loyalties and obligations owed others: ‘‘The ceremony has the effect of concentrating the attention of both individuals on every OTHER affectional tie either one has ever contracted’’ (Slater 1963, p. 354). The intrusion of the community into the couple’s relationship at the moment of unity serves to inhibit husband and wife from withdrawing completely into an intimate unit isolated from (and hence not contributing to) the larger social group.

Martin Whyte (1990) noted the lack of information on marriage rituals and conducted a study to help fill this gap. He found that, since 1925, wedding rituals (bridal shower, bachelor party, honeymoon, wedding reception, church wedding) have not only persisted but also increased in terms of the number of people who incorporate them into their wedding plans. Weddings also are larger in scale in terms of cost, number of guests, whether a reception is held, and so on. Like Slater, Whyte links marriage rituals to the larger social fabric and argues that an elaborate wedding serves several functions. It

1734

MARRIAGE

serves notice that the couple is entering into a new set of roles and obligations associated with marriage, it mobilizes community support behind their new status, it enables the families involved to display their status to the surrounding community, and it makes it easier for newly marrying couples to establish an independent household. (p. 63)

MARRIAGE AS PROCESS

Of the three ways in which marriage is conceptual- ized—institution, rite or ritual, and process—most scholarly attention has focused on process. Here the emphasis is on the interpersonal relationship. Changes in this relationship over the course of a marriage have attracted the interest of most investigators. Key issues studied by researchers include the establishment of communication, affection, power, and decision-making patterns; development of a marital division of labor; and learning spousal roles. The conditions under which these develop and change (e.g., social class level, age at marriage, presence of children) and the outcomes of being married that derive from them (e.g., degree of satisfaction with the relationship) are also studied. For illustrative purposes, the remainder of this article will highlight one of these components, marital communication, and one outcome variable, marital quality. We also address different experiences of marriage based on sex of spouse: ‘‘his’’ and ‘‘her’’ marriage.

The Process of Communication. The perception of a ‘‘failure to communicate’’ is a problem that prompts many spouses to seek marital counseling. The ability to share feelings, thoughts, and information is a measure of the degree of intimacy between two people, and frustration follows from an inability or an unwillingness to talk and listen (Okun 1991). However, when the quality of communication is high, marital satisfaction and happiness also are high (Holman and Brock 1986; Burleson and Denton 1997; Gottman 1994).

The role of communication in fostering a satisfactory marital relationship is more important now than in earlier times, because the expectation

and demands of marriage have changed. As noted above, marriage in America is less dependent on and affected by an extended kin network than on the spousal relationship. One of the principal functions of contemporary marriage is the nurturance of family members. Perhaps because this function and the therapeutic and leisure roles that help fulfill it in marriage are preeminent, ‘‘greater demands are placed on each spouse’s ability to communicate’’ (Fitzpatrick 1988, p. 2). The communication of positive affect and its converse, emotional withdrawal, may well be the essence and the antithesis, respectively, of nurturance. Bloom and colleagues (1985) suggest that one important characteristic of marital dissatisfaction is the expectation that marriage is a ‘‘source of interpersonal nurturance and individual gratification and growth’’ (p. 371), an expectation that is very hard to fulfill.

In the 1990s many studies focused on the relationship between communication and marital satisfaction (Burleson and Denton 1997). The findings from this body of research suggest that there are clear communication differences between spouses in happy and in unhappy marriages. Patricia Noller and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick (1990) reviewed this literature, and their findings can be summarized as follows: Couples in distressed marriages report less satisfaction with the social-emo- tional aspects of marriage, develop more destructive communication patterns (i.e., a greater expression of negative feelings, including anger, contempt, sadness, fear, and disgust), and seek to avoid conflict more often than nondistressed couples. Nevertheless, couples in distressed marriages report more frequent conflict and spend more time in conflict. In addition, gender differences in communication are intensified in distressed marriages. For example, husbands have a more difficult time interpreting wives’ messages. Wives in general express both negative and positive feelings more directly, and are more critical. Spouses in unhappy marriages appear to be unaware that they misunderstand one another. Generally, happily married couples are more likely to engage in positive communication behaviors (agreement, approval, assent, and the use of humor and laughter), while unhappy couples command, disagree, criticize,

1735

MARRIAGE

put down, and excuse more. Recently, Burleson and Denton (1997) explored the complexity of the communication–marital satisfaction relationship and found a variety of moderating factors: skills in communicating (realizing the communication goal, producing and receiving messages, social perception), the context or setting in which communication takes place, and the cognitive complexity of each spouse. They suggest that communication problems are best viewed as a symptom of marital difficulties and should not be seen merely as a diagnostic tool for distressed relationships.

Communication patterns may be class linked. It has long been found that working-class wives in particular complain that their husbands are emotionally withdrawn and inexpressive (Komarovsky 1962; Rubin 1976). Olsen and his colleagues (1979) assign communication a strategic role in marital and family adaptability. In their conceptualization of marital and family functioning, communication is the process that moves couples along the dimensions of cohesion and adaptability. In another study the absence of good communication skills is associated with conjugal violence (Infante 1989).

Differences between the sexes have been reported in most studies that examine marital communication. The general emphasis of these findings is that males appear less able to communicate verbally and to discuss emotional issues. However, communication is not the only aspect of marriage for which sex differences have been reported. Other components of marriage also are experienced differently, depending on the sex of spouse. The following paragraphs report some of these.

Sex Differences. In her now classic book, The Future of Marriage (1972), Jessie Bernard pointed out that marriage does not hold the same meanings for wives as for husbands, nor do wives hold the same expectations for marriage as do husbands. These sex differences (originally noted but not fully developed by Emile Durkheim in 1897 in Le Suicide) have been observed and examined by many others since Bernard’s publication (Larson 1988; Thompson and Walker 1989; Kitson 1992). For example, researchers have reported differences between husbands and wives in perceptions

of marital problems, reasons for divorce, and differences in perceived marital quality; wives consistently experience and perceive lower marital quality than do husbands.

Sex differences in marriage are socially defined and prescribed (Lee 1982; Blaisure and Allen 1995). One consequence of these social definitions is that sex differences get built into marital roles and the division of labor within marriage. For example, it has been observed that wives do more housework and child care than husbands (Thompson and Walker 1989; Presser 1994). Even wives who work in the paid labor force spend twice as many hours per week in family work as husbands (Benin and Agostinelli 1988; Coltran and IshiiKuntz 1992; Demo and Acock 1993). Wives are assigned or tend to assume the role of family kin keeper and caregiver (Montgomery 1992). To the extent that husbands and wives experience different marriages, wives are thought to be disadvantaged by their greater dependence, their secondary status, and the uneven distribution of family responsibilities between spouses (Baca Zinn and Eitzen 1990).

All these factors are assumed to affect the quality of marriage—one of the most studied aspects of marriage (Adams 1988; Berardo 1990). It will be the subject of our final discussion.

Marital Quality. Marital quality may be the ‘‘weather vane’’ by which spouses gauge the success of their relationship. The reader should be sure to differentiate the concept of marital quality from two other closely related concepts: family quality and the quality of life in general, called ‘‘global life satisfaction’’ in the literature. Studies show that people clearly differentiate among these three dimensions of well-being (Ishii-Kuntz and Ihinger-Tallman 1991).

Marriage begins with a commitment, a promise to maintain an intimate relationship over a lifetime. Few couples clearly understand the difficulties involved in adhering to this commitment or the problems they may encounter over the course of their lives together. More people seek psychological help for marital difficulties than for any other type of problem (Veroff et al. 1981). For a

1736

MARRIAGE

large number of spouses, the problems become so severe that they renege on their commitment and dissolve the marriage.

A review of the determinants of divorce lists the following problems as major factors that lead to the dissolution of marriage: ‘‘alcoholism and drug abuse, infidelity, incompatibility, physical and emotional abuse, disagreements about gender roles, sexual incompatibility, and financial problems’’ (White 1990, p. 908). Underlying these behaviors appears to be the general problem of communication. In their study of divorce, Gay Kitson and Marvin Sussman (1982) report lack of communication or understanding to be the most common reason given by both husbands and wives concerning why their marriage broke up. The types of problems responsible for divorce have not changed much over time. Earlier studies also list nonsupport, financial problems, adultery, cruelty, drinking, physical and verbal abuse, neglect, lack of love, in-laws, and sexual incompatibility as reasons for divorce (Goode 1956; Levinger 1966).

Not all unhappy marriages end in divorce. Many factors bar couples from dissolving their marriages, even under conditions of extreme dissatisfaction. Some factors that act as barriers to marital dissolution are strong religious beliefs, pressure from family or friends to remain together, irretrievable investments, and the lack of perceived attractive alternatives to the marriage (Johnson et al. 1999).

One empirical finding that continues to be reaffirmed in studies of marital quality is that the quality of marriage declines over time, beginning with the birth of the first child (Glenn and McLanahan 1982; Glenn 1991; White et al. 1986). Consequently the transition to parenthood and its effect on the marital relationship has generated a great deal of research attention (Cowen and Cowen 1989; McLanahan and Adams 1989). The general finding is that marital quality decreases after the birth of a child, and this change is more pronounced for mothers than for fathers. Two reasons generally proposed to account for this decline are that the amount of time couples have to spend together decreases after the birth of a child, and that sex

role patterns become more traditional (McHale and Huston 1985).

In an attempt to disentangle the duration of marriage and parenthood dimensions, White and Booth (1985) compared couples who became new parents with nonparent couples over a period of several years and found a decline in marital quality regardless of whether the couple had a child. A longitudinal study conducted by Belsky and Rovine (1990) confirmed the significant declines in marital quality over time reported in so many other studies. They also found the reported gender differences. However, their analysis also focused on change scores for individual couples. They reported that while marital quality declined for some couples, this was not true for all couples: It improved or remained unchanged for others. Thus, rather than assume that quality decline is an inevitable consequence of marriage, there is a need to examine why and how some couples successfully avoid this deterioration process. The authors called for the investigation of individual differences among couples rather than continuing to examine the generally well-established finding that marital quality declines after children enter the family and remains low during the child-rearing stages of the family life cycle.

Finally, the overall level of marital satisfaction is related to the frequency with which couples have sex (Call et al. 1995). The argument states that happy couples have sex more frequently, leading to more satisfying marriage, and that satisfaction in marriage leads to a greater desire for sex and the creation of more opportunities for sex.

Many students of the family have found it useful to consider marital development over the years as analogous to a career that progresses through stages of the family life cycle (Duvall and Hill 1948; Aldous 1996). This allows for consideration of changes in the marital relationship that occur because of spouses’ aging, the duration of marriage, and the aging of children. In addition to changes in marital quality, other factors have been examined, such as differences in the course of a marriage, when age at first marriage varies (e.g., marriage entered into at age 19 as opposed to in

1737