Книги по МРТ КТ на английском языке / Advanced Imaging of the Abdomen - Jovitas Skucas

.pdf

822

sities obtained from total prostate volume. The results depend on the ability to obtain accurate sonographic total prostate and transitional zone volumes.

Local Extension: Differentiation of intraprostatic tumor (pT2) from extraprostatic spread (pT3) has both prognostic and therapeutic implications, yet this differentiation is often made mostly on indirect evidence. Thus a Gleason score >7, perineural invasion, and most biopsies being positive argue for extraprostatic spread, while a low Gleason score or only one out of six positive biopsies suggest an intraprostatic tumor. A rough estimate of cancer spread can be based on the serum PSA level. In one study of men with prostate-confined tumors (pT2N0), mean total PSA was 7ng/ml, while in those with extracapsular spread (pT3pN0/N+) it was 10ng/ml (38)]; the free/total PSA ratios were not significant. A PSA level >20ng/ml has a specificity of almost 100%

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

in predicting extracapsular spread. Similarly, significant differences are evident in serum PSA levels between all T stages and metastases.

Study comparisons of tumor extension should be viewed critically; some authors use microscopic capsular penetration as detected by histology as their gold standard, while others rely on macroscopic criteria. Imaging detects gross morphological changes, thus its accuracy is limited in evaluating a disease notorious for microscopic tumor spread.

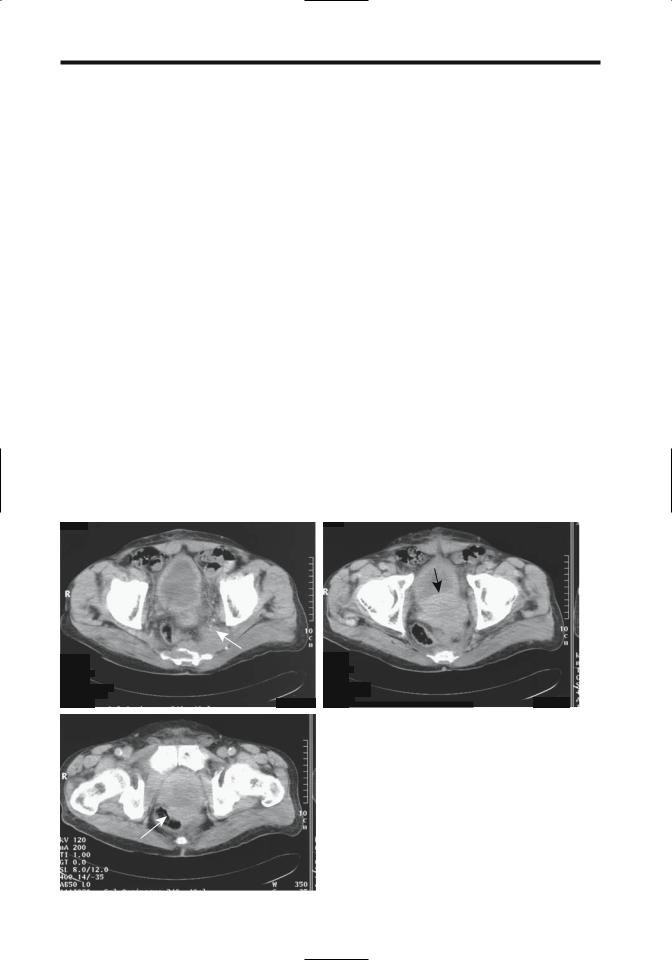

Computed tomography has a relatively low accuracy in staging local tumor extension; capsule penetration is difficult to detect (Fig. 13.4). Even invasion of seminal vesicles or lymph nodes correlates poorly with subsequent postoperative staging. In general, with a newly diagnosed, untreated prostate cancer and a serum PSA level of <20ng/mL, the likelihood of an abnormal CT finding is extremely low. Most published studies were done prior to the intro-

A |

B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 13.4. Three computed tomography (CT) images show an |

|

|

|

|

|

|

infiltrating prostatic carcinoma. Images reveal sacral and piriform |

|

|

|

|

|

|

muscle invasion (A, arrows), bladder invasion (B), and rectal inva- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

sion (C, arrows). (Courtesy of Egle Jonaitiene, M.D., Kaunas Medical |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

University, Kaunas, Lithuania.) |

|

|

|

|

|

823

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

duction of multislice CT, and the impact of this modality on prostate cancer staging remains to be established.

In men selected for radiation therapy, con- trast-enhanced abdominal and pelvic CT provide a low yield, and the need for this study, aside for treatment-planning CT, is questioned (39).

Although rather optimistic endorectal US staging results have been published, overall this modality has not lived up to expectations. Prospective studies suggest that endorectal US is no better than digital rectal examination in detecting extracapsular spread. In general, endorectal US does not detect about 25% of tumors and is not reliable in establishing extracapsular spread. Occasionally extraprostatic extension can be suggested if US can establish tumor contact with the prostate capsule.

Published reports of MRI staging of prostatic cancer should be interpreted with caution because study quality varies considerably among institutions, and interreader differences in interpretation exist. Thus among consecutive patients with MR studies read twice by two radiologists in random order, intraobserver and interobserver agreement ranged from fair to good (33). Published MR staging accuracies for local extension vary considerably. Sensitivities of capsular penetration range from 15% to 85% and seminal vesicle invasion from 25%; published specificities have a similar wide variability. Conclusions range from MR being better than US to endorectal coil MRI having insufficient staging accuracy to influence treatment planning. Some studies suggest that cancer detection rates improve with contrast enhancement, while others do not (40). In general, use of an endorectal coil, a breath hold technique and multiple imaging planes aid staging. A multivariate analysis concluded that adding endorectal MR imaging findings to serum PSA levels and percent of cancer in core biopsies improved prediction of extracapsular invasion (41). Use of a 3T magnet improves staging accuracy but further work is needed.

An MR finding of rectoprostatic angle obliteration and neurovascular bundle asymmetry are predictive of extracapsular extension. Macroscopic capsular penetration is identified as capsular discontinuity and invasion of adjacent adipose tissue. One should keep in mind, however, that a prior biopsy can also result in

capsular irregularity without tumor invasion (42). Tumor spread to seminal vesicles is seen on T2-weighted MR images as a low signal intensity region replacing part of a seminal vesicle. Infiltration can be either unilateral or bilateral. An early finding is thickening of seminal vesicle tubules. Asymmetrical seminal vesicle enlargement should raise suspicion for tumor involvement. With diffuse tumor spread to the seminal vesicles the appearance mimics that of an inflammatory condition.

Stage of seminal vesicle invasion is predictive of postoperative disease progression. To some degree the number and site of positive prostatic sextant biopsies correlate with seminal vesicle invasion; seminal vesicle infiltration correlates with the presence of positive basal prostatic biopsies. Seminal vesicles are amenable to direct biopsy using US guidance. Most of these biopsies are performed lateral to the prostate, in the medial third of the seminal vesicle. A negative biopsy does not exclude tumor spread to the seminal vesicle, with eventual histology identifying seminal vesicle invasion in up to one third of men with negative biopsies, and such biopsies contribute little to staging.

Seminal vesicles invasion ranges from proximal part involvement to extension to the free end, with the latter signifying a worse prognosis. Thus a biopsy identifying invasion to the free end influences the prognosis after radical prostatectomy.

Lymph Node Involvement: Lymph node involvement with prostatic cancer is of prognostic significance. Even microscopic spread is associated with a poor prognosis. Currently the only reliable means of detecting early nodal involvement is either resection or biopsy, although a high Gleason score or a PSA >20ng/mL implies an increased risk of node involvement.

The current therapy of most biopsy-proven prostatic carcinomas is radical prostatectomy. On the other hand, a radical prostatectomy by itself is not warranted if nodal metastases are present. Therefore, detection of lymph node metastasis is crucial, and pelvic lymph node dissection is used to stage these cancers. In such a setting the preoperative ability of imaging to assess lymph node disease is important. Imageguided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (actually, cytology) of pelvic and para-aortic nodes

824

appears worthwhile if suspicious nodes are identified.

Preoperative imaging tends to underestimate the degree of lymph node involvement. Routine use of cross-sectional imaging (CT or MRI) to determine whether pelvic lymph node metastases are evident is controversial, yields a low accuracy, and is probably not justified; in select men at high risk for nodal metastasis, however, such as with an elevated PSA level, it appears cost-effective, keeping in mind that CT provides only indirect evidence of nodal involvement, namely, enlarged nodes. Generally 1cm is used as a border between normal and abnormal nodes. Computed tomography sensitivity can be improved if a smaller limit is selected, but at the expense of worse specificity. Computed tomog- raphy–guided node biopsy can then be considered, although localization problems arise with smaller nodes.

Currently the primary MRI criterion useful in identifying lymph node metastasis is node size. Ferumoxtran-enhanced MRI detection of metastasis to normal-sized pelvic lymph nodes needs further study.

At times a diagnosis is not straightforward even with generalized lymphadenopathy; a lymphoma can be suspected if adenopathy is detected prior to the prostate cancer. These men generally undergo node biopsies, which reveal an adenocarcinoma, leading to a workup for a primary site.

Detection of pelvic lymph node metastases with FDG-PET is limited because of superimposed bladder tracer activity.

Radioimmunoscintigraphy with indium- 111–capromab pendetide achieve sensitivities and specificities for pelvic lymph node metastases superior to most other imaging studies.

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

Also, capromab specificity can be improved further by combining results with pelvic CT and MRI (43).

The efficacy of lymphangiography in assessing lymph node involvement is low, even when combined with CT or biopsy, and currently lymphangiography is rarely performed for this indication, having been supplanted by newer imaging modalities.

Men with localized prostate cancer who undergo endorectal US with systematic sextant biopsies can be divided into three groups (Table 13.3); those meeting group III criteria should undergo pelvic lymphadenectomy (44). A positive seminal vesicle biopsy is also a predictor of pelvic lymph node metastases; perineural invasion is an independent predictor.

Distal Spread: Using systematic six-sextant prostatic biopsy as a guide, a significant relationship exists between the number of positive biopsy cores and bone metastasis. With a newly diagnosed prostate cancer and a PSA level of <10ng/mL, the probability of detecting bone metastases with a bone scan is probably <1%, and a bone scan thus appears unnecessary if no clinical signs of bone involvement are evident. Yet the PSA level is somewhat limited in discriminating between those with and those without bone metastases, and some authors have questioned whether a staging radionuclide bone scan can indeed be omitted in those with a serum PSA level of <10ng/mL.Yet among men with a localized prostate cancer and a PSA level of <20ng/mL, 3% had bone metastases (45); the authors concluded that bone scintigraphy is necessary when staging these tumors. Others disagree. One should keep in mind that bone metastases occur in some men after therapy of a primary tumor even with an initially negative

Table 13.3. Results of pelvic lymphadenectomy in 130 men with localized prostate cancer

|

Preoperative findings |

Lymphadenectomy results* |

|

|

|

Group I |

Negative basal biopsies, and clinical stage T2 |

All had negative lymph nodes |

|

(irrespective of PSA) |

|

Group II |

Positive basal biopsy, and clinical stage T2, |

All but one were lymph node negative |

|

and PSA <10 ng/mL |

|

Group III |

Positive basal biopsy, and/or clinical stage T3, |

17 of 18 with positive nodes were in this group |

|

and/or PSA >10 ng/mL |

|

|

|

|

* Radical prostatectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy revealed that 18 of the 130 patients had positive pelvic lymph nodes. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Source: Adapted from Dunzinger et al. (44).

825

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

bone scan and a question arises whether metastatic cancer cells were already present at the time of initial therapy but were undetected by a bone scan? Bone marrow aspirates from men with no evidence of metastatic disease suggests that some already have micrometastases.

Bone scintigraphy is the current procedure of choice to detect bone metastases. Positive bone scintigraphy should be correlated with appropriate bone radiographs to exclude degenerative changes as a cause for a positive uptake; bone radiography per se is insensitive in detecting early bone metastases.

Magnetic resonance imaging using short T1 sequences is becoming a viable alterative to bone scintigraphy. Currently, MR is employed in evaluating inconclusive bone scans, although the evidence suggests that it is more sensitive than scintigraphy in detecting bone metastases. Bone radiographs are less sensitive but are of use as an aid in detecting false-positive scintigraphy due to degenerative disease. 2-[18F]- fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose PET is less sensitive than scintigraphy in detecting bone metastases. Further imaging studies are generally pointless once bone metastases are detected.

A solitary metastasis to the peripheral skeleton is relatively uncommon, but at times has an atypical appearance.

Lung metastases are a late event, and thus chest radiographs are not indicated during the initial follow-up.

Prostatic cancer metastasis to the ureter, either via lymphatics or hematogenously, can manifest as renal colic. Ureteral obstruction secondary to metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma is amenable to balloon dilation and subsequent antegrade Wallstent insertion.

Penile metastasis from prostate cancer is rare. Some of these appear to be related to prior urethral catheterization, and transurethral prostatectomy.

Therapy

Current therapy consists of surgery in its various modifications, radiotherapy, androgendeprivation therapy, or simply a wait-and-see approach.

Surgery is the accepted therapy for newly diagnosed prostate cancer in many centers, especially in the United States.A not uncommon

scenario for low-grade and localized tumors is staging lymphadenectomy, and if frozen section reveals these to be not involved, proceeding to radical prostatectomy.

Given the low inherent mortality associated with a number of these cancers, however, conservative management, especially in frail and elderly men, continues to be employed, and androgen-deprivation therapy is more often employed in these men, especially outside the United States. The boundary between surgery and conservative management is a controversial topic but with time is gradually tilting more toward surgery, given the more frequent detection of early cancers and resultant low surgical morbidity and mortality.

The presence of tumor spread beyond the prostatic capsule generally reflects a change from surgery to radiotherapy, although no precise changeover point is defined. Prostatectomy and either lymph node resection or radiotherapy for nodal metastasis result in a high rate of recurrence. Androgen-deprivation therapy is considered with lymph node involvement.

Radical prostatectomy is generally considered the gold standard in treating localized prostate cancer. Yet a number of these prostatectomies, performed for stage T1c disease, reveal potentially insignificant tumors. Although the term insignificant in this context is difficult to define, a typical definition consists of a cancer confined to the prostate, a tumor volume <0.5cc, and a Gleason score of <7 (46). Relatively clear indications exist for radical prostatectomy, yet considerable variations in surgical practice exist, even in the same country. Thus a 2001 survey in France found that the probability of being treated by radical prostatectomy was three times higher in one department compared to others and 2.6 times higher in private practices (47). Such variability introduces another variable when analyzing survival data.

A laparoscopic radical prostatectomy is feasible, with reported outcomes similar to those of a conventional retropubic approach.

Intraoperative endorectal US during radical retropubic prostatectomy is helpful in identifying the urethral division site but is not commonly employed.

Complications after a radical prostatectomy include rectal injury, abscess, major hemorrhage, anastomotic urinary leakage, anastomotic stricture, and lymphocele formation.

826

Cystography is commonly obtained a week or so after radical prostatectomy to assess the vesicourethral anastomosis. If extravasation is detected, as long as a catheter is left in place until healing, the extravasation does not influence subsequent stricture formation. Another approach is simply to keep the catheter in place for 14 to 21 days, without cystographic confirmation of anastomotic integrity. Computed tomography after a radical prostatectomy often reveals a complete or incomplete transverse bar of soft tissue in the rectovesical space. This is a normal postoperative finding.

After a radical prostatectomy the bladder neck widens and assumes a funnel-shaped appearance. This defect is readily identified with endorectal US and cystography. Ultrasonography also reveals a hypoechoic tumor surrounding the vesicourethral anastomosis and indenting the bladder anterior wall. Eventual fibrosis results in a hypointense signal on T2-weighted MR images.

Radiotherapy: Radiotherapy has a role in treating pelvis-confined prostate cancer. External radiotherapy combined with hormone therapy in men with cT2 prostatic adenocarcinoma achieved a 100% overall 5-year survival. Even with incurable prostate cancer, radiotherapy delays tumor regrowth and achieves a several-year delay in tumor progression in most men. In men with clinically localized prostate cancer, progression-free and overall survival rates are significantly improved if androgen ablation is added to radiotherapy.

Follow-up of patients after radiotherapy consists of digital rectal examination and PSA level. Serum PSA decreases but it does not drop to undetectable levels as occurs after resection. A rising PSA signifies tumor growth and should prompt bone scintigraphy. If scintigraphy is positive, no further workup is needed. Magnetic resonance imaging has a role in a setting of a negative or indeterminate bone scan and a rising PSA level.

Hematochezia is common after prostate radiation therapy. One should not ascribe all bleeding to such therapy; some men have concomitant bowel disease, including colon cancer.

Brachytherapy is potentially curative for either initial or recurrent localized prostatic cancer. Computed tomography– or transrectal

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

US-guided implants consist either of palladium 103 or iodine 125, at times supplemented with external beam radiotherapy. A urethrorectal fistula developed in 1% of men undergoing brachytherapy (48); interestingly, all fistulas were in those who also had anterior rectal biopsy adjacent to the prostate.

Coronal T2-weighted endorectal MRI in 35 consecutive patients after brachytherapy for prostate cancer reveals a diffuse hypointense signal and indistinct zonal anatomy (49); both intraand extraprostatic seeds can be identified. Endorectal MRI evaluates both seed distribution and brachytherapy-related changes. Recurrent cancer has early contrast enhancement on dynamic MRI; focal peripheral zone early enhancement greater than in the central zone suggests recurrence.

Cryoablation: Transperineal percutaneous cryoablation using endorectal US-guidance has received considerable interest in treating localized prostate cancer; preliminary studies are encouraging. Posttherapy PSA levels are of prognostic significance; those with a PSA level >0.5ng/mL are likely to have residual disease.

Salvage cryoablation is occasionally performed in men with locally recurrent prostate cancer after radiation, hormonal therapy, or systemic chemotherapy. This procedure is associated with significant morbidity, including urinary incontinence, obstruction, and impotence.

A cryoshock phenomenon consisting of multiorgan failure, severe coagulopathy, and disseminated intravascular coagulation has been described after liver cryotherapy. A multiinstitution questionnaire identified two instances of cryoshock after prostatic cryoablation (out of 5432 patients) (50). An uncommon complication after cryoablation is necrosis of the symphysis pubis.

Endorectal US 3D prostate images are used by some investigators for probe placement and monitoring during cryoablation, realizing that in this setting endorectal US achieves a low sensitivity in detecting residual prostate carcinoma and is not reliable for this indication.

Magnetic resonance imaging after cryoablation reveals liquefactive necrosis in the prostate bed and a decrease in prostate volume with loss of zone differentiation. Necrotic regions appear as a signal void on postcontrast MRI. A thick

827

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

capsule surrounds the gland postablation. Magnetic resonance does not differentiate cryosurgery-induced changes from recurrent tumor, and a baseline posttherapy study is thus very useful.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy after cryosurgery reveals that necrotic tissue does not contain any observable choline or citrate and MR spectroscopy thus is useful to gauge success of therapy.

Prominent uptake of Tc-99m–methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is evident within the prostate bed after cryoablation, presumably due to neovascular hyperemia.

Other Therapy: During percutaneous radiofrequency (RF) ablation of prostate cancer, RF energy is delivered through needle electrodes inserted transperineally using endorectal US guidance. Preliminary results appear promising. Extensive coagulation necrosis develops in involved tissues.

Magnetic resonance imaging can monitor percutaneous interstitial microwave thermoablation (51); MRI-derived temperatures reflected tissue temperatures.

Therapy with transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound is feasible, but the role of such therapy is not clear. Among men with clinical stage T1 or T2 prostatic cancer, not eligible for a radical prostatectomy, treated by transrectal high-intensity focused ultrasound, negative follow-up biopsies were obtained in 61% (52); of concern are the complications—rectourethral fistulas, rectal burns, urinary retention, severe incontinence, bladder neck scleroses, and urinary tract infection.

A permanent metal stent can be inserted in high surgical risk men with bladder outlet obstruction.

Leuprolide, an agonist of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone, and flutamide, an antiandrogen, are some of the agents used for androgen-deprivation therapy of localized prostate cancer. These agents result in gland shrinkage and decrease of high-grade intraepithelial tumors, but invariably residual tumor remains. After androgen-deprivation therapy, MR shows tumor volume and signal intensity decreasing, together with a reduction in tumor permeability as measured by contrast enhancement parameters (53); one effect is poorer tumor visualization. One should keep in mind that androgen-deprivation therapy tends to

suppress serum PSA levels, and these levels thus may not accurately reflect disease activity, although a rising level warrants further study.

Outcome/Follow-Up

Clinical: Especially in elderly and high-risk men, some small prostate cancers are treated conservatively. Such an approach requires caution because many of these men will eventually die of their prostatic cancers. Thus a retrospective study of men with a known diagnosis of prostate cancer who died in Göteborg, Sweden, during a specific time period, and who underwent hormonal therapy, found that among those who survived at least 10 years, the mortality rate due to prostate cancer was 63% and this mortality increased steadily over time (54); even among those in stage M0 at initial diagnosis, 50% died of prostate cancer.

The 5-year survival rate for those with pathologic stage III or higher tumors, treated by radical prostatectomy and adjuvant hormone and radiation therapy, is over 80%. Life expectancy is unpredictable in some men even with metastases. Thus some men with metastatic prostate cancer survive for more than 5 years; size and primary tumor differentiation are prognostic survival factors. Nevertheless, even with prostatectomy specimen Gleason score 8 to 10 tumors, a preoperative serum PSA level £10ng/mL and organ-confined disease are significant predictors of achieving prolonged disease-free survival (55).

Serum PSA levels and a digital rectal examination are used for follow-up to detect recurrence after therapy. After a radical prostatectomy serum PSA levels should be undetectable within several weeks unless residual disease is present. Any subsequent detectable level implies relapse. Yet follow-up of men after a radical retropubic prostatectomy for clinically localized (£T2) disease who then had an elevated postoperative PSA level revealed that 94% of these men had no evidence of metastatic disease (based on a bone scan) 5 years from the time of PSA elevation, and 91% had no such evidence at 10 years (56).

Initially during radiotherapy serum PSA increases (57), then decreases but does not drop to undetectable levels as found after resection. Follow-up of these patients consists of digital

828

rectal examination and monitoring PSA levels. A rising PSA should prompt bone scintigraphy. If scintigraphy is positive, no further workup is needed. Magnetic resonance imaging has a role in a setting of an indeterminate bone scan. A rising PSA level and negative bone scintigraphy suggests local recurrence and transrectal USguided biopsy and CT or MR for adenopathy appear appropriate.

In men with inoperable prostate cancer, radionuclide bone scans, serum PSA, and serum prostatic acid phosphatase levels monitor progression, although some investigators believe that serum PSA level by itself is sufficient to follow disease progression. Men with untreated prostatic cancer or those refractory to endocrine therapy have an exponential increase both in PSA level and in prostatic acid phosphatase level; tumor marker doubling time is a useful guide in estimating cancer growth rates and in determining prognosis after relapse.

Urinary PSA levels are not useful for posttherapy follow-up because PSA is also secreted by periurethral glands.

Imaging: Postoperative recurrence is either local or metastatic. Computed tomography sensitivity in detecting local recurrence is low, with postoperative deformity making evaluation difficult. Endorectal US is more sensitive but less specific than digital rectal examination for detecting local recurrence although both provide only limited information (58). Adding Doppler US improves both sensitivity and specificity. With an elevated serum PSA level and a negative bone scan, US-guided prostate fossa biopsies should be considered, especially of any hypoechoic foci detected by endorectal US. Negative biopsies, however, are of limited significance.

For detecting local recurrence, an endorectal coil MRI study is superior to a body coil MRI study. Endorectal surface coil MRI sensitivities and specificities close to 100% have been enthusiastically reported in detecting local recurrence and some authors believe that endorectal MRI has a place in those who have had a prostatectomy and local recurrence is suspected (59). Nevertheless, one study found poor accuracy, and solid tumor foci were detected only if they were >1cm in diameter, while diffuse tumor infiltration was not detected (60). The authors also found that contrast-enhancement provided no additional information, and they concluded

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

that in this setting MRI cannot replace follow-up biopsy. When seen, recurrence is identified as a soft tissue tumor in the prostatic bed, which is hypoto isointense on T1and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. A fibrotic peripheral zone is hypointense.

Monoclonal antibody radioimmunoscintigraphy with In-111–capromab pendetide shows promise in detecting occult recurrence. This antibody conjugate localizes to a glycoprotein found primarily on prostate tissue cell membranes. In men with an elevated serum PSA at least 3 months after therapy, monoclonal antibody imaging was superior to PET scanning in identifying recurrent cancer; most common sites of recurrence are prostatic fossa and lymph nodes.

Small Cell/Anaplastic Carcinoma

A nondifferentiated small cell prostatic carcinoma is rare. These are aggressive tumors associated with a poor prognosis. These tumors often exhibit morphologic and functional neuroendocrine characteristics. Superficially, some mimic a lymphoma. The CEA levels tend to be normal.

Computed tomography often detects metastatic disease in men presenting with an anaplastic prostate carcinoma; bone metastases are associated with a more modest PSA level compared to a typical prostatic carcinoma.

Lymphoma/leukemia

Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the prostate is rare. Clinically, these lymphomas can mimic acute prostatitis.

Secondary hematologic malignancies involving the prostate and adjacent lymph nodes range from chronic lymphocytic leukemia to lymphoma. Transrectal US–guided prostate biopsies should be diagnostic.

An occasional outlet obstruction is the first manifestation of a leukemic or lymphomatous prostatic infiltrate.

Mesenchymal Neoplasms

Prostatic leiomyomas are rare. These tumors can be quite large and imaging findings nonspecific. A diagnosis is established with a biopsy.

829

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

Of clinical importance are postoperative spindle cell nodules and pseudosarcomatous fibromyxoid tumors; pathologically, these tumors may be misidentified as sarcomas.

Most prostatic sarcomas occur in children under 10 years of age, thus allowing differentiation from carcinoma. Most of these are rhabdomyosarcomas. In adults about 25% of prostatic sarcomas are leiomyosarcomas. Previous pelvic radiation, such as for a seminoma, is occasionally associated with a prostate sarcoma. These tumors tend to be large at initial presentation.

Ultrasonography identifies most prostatic sarcomas as heterogeneous tumors having decreased attenuation, probably due to focal necrosis.

These sarcomas are hyperintense on T2weighted MRI, with the surrounding fibrosis being hypointense.

Wolffian Duct Structures

Endorectal US appears to be a reasonable first study in evaluating the distal male reproductive tract for potentially correctable causes of infertility. Cysts and duct obstructions are detected.

Seminal Vesicle Disorders

Seminal vesicle cysts can be either congenital or acquired. They are located posterolateral to the bladder in the general location of the seminal vesicles. An occasional one is more midline in location and inhomogeneous in appearance. Most cysts are unilateral and more frequent on the right side. A cyst can obstruct an adjacent seminal vesicle.A rare cyst is huge. Most of these cysts are discovered incidentally. An association exists between seminal vesicle cysts and absence or dysplasia of the ipsilateral kidney. An ectopic ureteral insertion into the seminal vesicle is found in some of these patients; the presence of a seminal vesicle cyst thus warrants further imaging; both structures originate from a common embryologic mesonephric duct.

Multiple, bilateral seminal vesicle cysts develop in men with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Computed tomography density tends to be >40 Hounsfield units (HU) in seminal vesicle cysts. Endorectal US readily identifies these

retrovesically located cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging is also very useful in detecting seminal vesicle cysts, which are hyperintense on both T1and T2-weighted images.

Transperineal puncture under endorectal US guidance fills a cyst with contrast and establishes the diagnosis. Most seminal vesicle cysts are resected; a minority undergo transurethral marsupialization using endorectal US guidance.

In temperate climates the most common cause of seminal vesicle calcifications is diabetes mellitus. Schistosomal calcifications are encountered in the Near East. Less often calcifications are secondary to tuberculosis. Seminal vesicle calculi are associated with painful ejaculation. Endorectal US detects duct obstruction by stones or fibrosis. Calcifications are hypointense on both T1and T2-weighted MRI.

Seminal vesicle hydatid cysts are rare. CT reveals thin wall water-density cysts (61); some also develop daughter cysts.An infected cyst can evolve into an abscess. These abscesses can be drained percutaneously.

An infected cyst can evolve into an abscess. These abscesses can be drained percutaneously.

Most seminal vesicle neoplasms are reported anecdotally. A rare cystadenoma mimics a cyst.

Rarely, amyloidosis infiltrates the seminal vesicles.

Ejaculatory Duct Disorders

An ejaculatory duct cyst adjacent to the duct can occlude the duct lumen. Some of these cysts are associated with infertility. These cysts are identified and treated using endorectal US guidance. Their aspirate contains spermatozoa, thus distinguishing these cysts from müllerian duct cysts.

Occasionally identified is urethroseminal reflux into the ejaculatory ducts.

Endorectal US–guided opacification of the seminal tracts with contrast is useful in men with suspected ejaculatory duct obstruction and dilated seminal vesicles. Most ejaculatory duct obstructions are bilateral.

Hemospermia

Causes of hemospermia include prostatitis, seminal vesicle or ejaculatory duct calcifications, cysts, and vascular anomalies. End-

830

orectal gray-scale and Doppler US determine the cause of hemospermia in most in men. Detected are periurethral calcifications, prostatic inflammation, seminal vesicle ectasia, and various cysts. Magnetic resonance using an endorectal coil is probably more sensitive. Hyperintense seminal vesicles on T1-weighted images suggest hemorrhage, and hypointense ones both on T1and T2-weighted images consist of fibrosis due to chronic inflammation.

Penis

Urethra

Extravasation/Fistula

Unusual causes of anterior urethral fistulas are involvement by Crohn’s disease and infection by tuberculosis and schistosomiasis. An occasional primary adenocarcinoma originates in a urethrorectal fistula.

Most catheters inserted through a urethral perforation are readily apparent on a contrast study. A urethroscrotal fistula leads to massive scrotal enlargement. These are readily apparent with imaging; bone scintigraphy reveals an appearance similar to a scrotal bladder.

Obstruction

In adult men the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction is BPH. Less common are prostate, bladder and related structure neoplasms, inflammation, urethral strictures, and a neurogenic bladder. Urethral valves as a cause of obstruction are of more importance in the pediatric age group.

ADVANCED IMAGING OF THE ABDOMEN

called sonourethrography) also appears to have a role. Sonourethrography evaluates both length and severity of a stricture. It visualizes not only strictures but also associated corpus spongiosum fibrosis which ranges from isoto hyperechoic to the corpus spongiosum.

With recurrent posterior (bulbar) urethral strictures, initial balloon angioplasty followed by insertion of an expandable metallic stent appears worthwhile; short-term results are satisfactory, but some men develop an exuberant fibrotic reaction requiring either a urethrotomy or urethroplasty.

A bioabsorbable self-expandable reinforced poly-l-lactic acid spiral stent shows promise. Inserted immediately after urethrotomy in men with recurrent urethral strictures, all but one stent was epithelialized at 6 months and degraded in all at 12 months (62).

Urethral Valves

Posterior urethral valves were discussed earlier (see Congenital). Anterior urethral valves rarely result in obstruction. Similar to posterior urethral valves, they are usually detected with a voiding cystourethrogram.

Calculi

Urethral calculi are either primary or secondary. Primary calculi develop in a diverticulum, proximal to a stricture,or in the presence of a foreign body. Secondary calculi pass from the bladder.

Urethral calculi are best detected by conventional radiography; they can be missed during a contrast study if only contrast-filled images are obtained.

Stricture

Distal to the prostate, the most frequent acquired abnormality of the male urethra is a benign urethral stricture. An uncorrected stricture eventually leads to hydronephrosis, chronic pyelonephritis, vesicoureteral reflux, and renal failure. These complications often are irreversible.

A rare cause of urethral obstruction is primary amyloidosis of the penile urethra these strictures are amenable to urethral dilation.

Urethral strictures are studied by a retrograde urethrogram. Ultrasonography (also

Verumontanum Hyperplasia

Hyperplasia of verumontanum mucosal glands is a rare cause of urethral obstruction. Occasionally a prostatic biopsy suggests a low grade adenocarcinoma, but in reality it represents hyperplasia of verumontanum mucosal glands.

Functional Obstruction

The clinical role of endorectal US while voiding is yet to be established. It has been used to study suspected dysfunctional voiding when more obvious causes are excluded; voiding US detects

831

MALE REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS

abnormal motion of the posterior urethra during voiding.

Occasionally voiding cystourethrography detects extreme posterior urethral ballooning and a disproportionate caliber between the posterior and penile urethra; in some individuals a kink is identified between the two segments, but in others no obvious obstruction is identified.

Diverticulum

Urethral diverticula are rare in males. Congenital ones predominate in young boys, while in adults most are secondary either to previous trauma or an adjacent abscess rupturing into the urethra. Urethral diverticula develop in men with spinal cord injuries. Stones tend to form within these diverticula, presumably due to stasis. Diverticula close to the fossa navicularis are associated with meatal stenosis.

Neoplasms, including a nephrogenic adenoma, can develop in an urethral diverticulum.

Diverticula are detected by US, CT, and MRI. More proximal ones mimic a müllerian duct cyst or a dilated utricle and are midline in position. These outpouchings are readily identified with a voiding cystourethrogram, which reveals a diverticulum filling and compressing the urethra during voiding and then emptying at the end of micturition. Differentiation from an anterior urethral valve is difficult in some individuals; keep in mind that the pathogenesis of some urethral diverticula and anterior urethral valves appears similar.

Tumors

Urethral

Polyps in the male urethra are rare; most are not neoplastic and tend to occur in the posterior urethra. Some fibroepithelial polyps are pedunculated and at times reflux into the bladder at rest. Schistosomiasis also results in urethral polyps. Obstruction is the most common presentation.

Either a voiding cystourethrogram or retrograde urethrogram should detect a polyp. The differential diagnosis for a polyp detected with a urethrogram includes an ectopic ureterocele; US should differentiate between these two con-

ditions because a polyp is hyperechoic while a ureterocele is anechoic.

Condyloma acuminata is seen as multiple intraluminal urethral tumors. They tend to have a shaggy, irregular appearance.

A urethral hemangioma is a benign vascular tumor. Hematuria is a typical presentation. At times postejaculation hematuria or clotinduced urinary retention develops. Treatment is surgical, although depending on the size and number of lesions, selective arterial embolization may be worthwhile.

Primary urethral adenomas and carcinomas are uncommon. They tend to evolve in a setting of superimposed chronic disease. The histology of these tumors varies; posterior urethral cancers tend to be transitional cell carcinomas, anterior urethral ones often are squamous cell carcinomas, and Cowper’s or Littre’s gland tumors are adenocarcinomas. A rare transitional cell carcinomas develops in the fossa navicularis; some of these are associated with synchronous or metachronous more proximal transitional cell carcinomas. An occasional adenocarcinoma in situ is detected in a villous adenoma. Chronic strictures predispose to cancer, generally a squamous cell carcinoma; these cancers tend to be irregular in outline. The rare urethral epidermoid carcinoma is also associated with a prior urethral stricture and related complications.

Smaller transitional cell carcinomas often present as intraluminal urethral nodules; with growth they infiltrate the adjacent structures. A rare transitional cell carcinoma is occasionally detected in the fossa navicularis. Squamous cell carcinomas infiltrate and often ulcerate. At times a blood clot mimics a malignancy, although blood clots tend to be more irregular and elongated in appearance. Sinus tracts developing in some cancers mask the underlying tumor, which is often detected by finding marked progression between examinations.

Primary malignant melanoma is more common in the distal urethra and tends to be polypoid in appearance. The histopathology is similar to that of melanomas at other sites. Occasionally confusing the pathologic diagnosis is an amelanotic appearance. An occasional one mimics a urethral carcinoma.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the urethra is rare. Urethral obstruction is a typical presentation.