- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

discovered, but where the tablets have been found, they are clear and well preserved. Excavation of an archive room in an Urartian citadel is a real possibility, and it would revolutionize our understanding of the Urartian language and the lives of Urartian citizens who were not kings.

URARTIAN RELIGION AND CULTIC ACTIVITIES

In all probability there was a wide variety of popular religious activity in addition to the official cult in Urartu, but it is only the latter that we know anything about. The formation of a state religion was an important step in the creation of the state of Biainili.44 The god Haldi, whose primary cult center was at Musasir, appears in Assyrian records of the second millennium BC, but is not particularly prominent. In the reign of Ishpuini, if not earlier, he was elevated to the head of the Urartian pantheon and remained overwhelmingly the most important deity until the kingdom came to an end, after which he disappears from the historical record.45

The pantheon Haldi led included a few gods who are important in the Hurrian religion of the second millennium, specifically the Storm God, called Teisheba by the Urartians, and the Sun God, Shiuini (probably pronounced Shiwini).46 The trio of Haldi, Teisheba, and Shiuini not only head the lists of gods in texts which ordain sacrifices, but is also invoked in the curse formulae that conclude some royal inscriptions, threatening those who damage the monument or claim it as their own. Ranking below these gods were several others who appear in multiple inscriptions and thus may be regarded as having importance in the kingdom as a whole. Scores of others, known only by name, are mentioned only once.

No Urartian Yazılıkaya has been discovered, but we get a good idea of the hierarchy from a lengthy inscription carved in an outcrop on the northern outskirts of Van. Meher Kapısı (the “Door/Gate of Mithra”) as this is now known, is a false door with a frame that takes the same form as temple entrances on Urartian citadels. Within the frame is a 94-line text in which Ishpuini and Minua list quantities of animals to be sacrificed to individual gods in the month of the Sun

God. The quantities and values of the animals offered to each god diminish as one moves down the list, starting with 17 bovids and 34 sheep to Haldi and finishing with individual animals for lesser gods. Below the framed text are benches and grooves carved in the rock where the animals could be sacrificed and the blood channeled off.

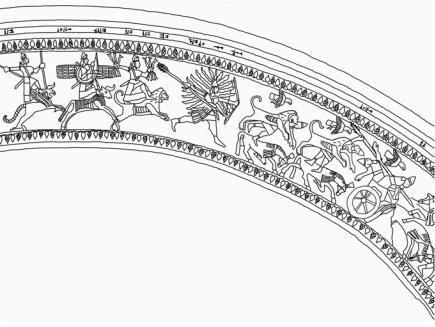

A unique pictorial representation of the ranking gods in anthropomorphic form appears on a fragment of a bronze shield discovered in the fortress of Upper Anzaf.47 It shows the god Haldi impaling enemies with his sˇuri, the weapon with which he campaigns in Urartian texts (Figures 9.18 and 9.19).48 Behind him comes a procession of gods astride animals, brandishing their own weapons. Teisheba on a lion and Shiuini on a bull are identifiable by their thunderbolts and winged sun disc, respectively, and then come other gods riding mythical animals. The identification of these is by no means certain, although the hypothesis that they follow the order of the Meher Kapısı text is not ruled out.

Meher Kapısı should not be seen as a canonical Urartian pantheon for the entire kingdom or

342

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

Figure 9.18 Bronze shield fragment from Anzaf with an inscription of Minua, showing the gods in battle (after Belli 1999; Seidl 2004: 85)

the full sweep of Urartian history, however. At other sites gods who are of minor importance or not mentioned at all on the list enjoy great prominence. For example, one of the two wellpreserved temples excavated at Çavus¸tepe, in the heart of the citadel itself, is dedicated to the god Irmushini. He, or she, is the only named deity at this very important site49 yet there is nothing much to distinguish him from other gods at Meher Kapısı, where he appears well down in the list. Iubsha or Iarsha, the deity of the temple at Erebuni built by Argishti I, is not mentioned on the list at all. The mountain god Eiduru is prominent at Ayanis, not unexpectedly as this mountain is used to specify the location of the site, yet he does not make the list either, even though Ayanis is not far from the cliff on which the Meher Kapısı inscription was carved. It would appear local gods were worshiped as they came to the attention of the monarchy, and that the pantheon was hardly systematized below the upper levels of its hierarchy.

The construction of temples within royal fortresses highlights the strong association of the state with religion in Urartu. One particular form of temple appears only in this context. It has a square ground plan with thick walls and reinforced corners (Figure 9.14) which suggest it took the form of a tower.50 Near the back wall of the single room cella was a podium on which a cult image of some sort was presumably placed. At Ayanis there was an elaborately decorated alabaster platform in this location,51 and in the temple Toprakkale it would appear that the first excavators in Urartu uncovered the remains of a throne.52 Decorative schemes of the temples themselves vary, ranging from simple, unadorned ashlar masonry at Altıntepe to the elaborate

343

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

Figure 9.19 Bronze sˇuri (weapon) of Haldi, from Ayanis (after Seidl 2002: 92)

display at Ayanis, with an inscription covering the entire facade and inlaid animals and deities lining its interior. In any case, the embrace of church by state appears to be very close and no Urartian inscription mentions a priesthood or any other institution intervening between the king and the god.

About religious activities other than royal sacrifices, we are largely in the dark. Seals and bronzes often depict mythical creatures including protective deities, griffins, and centaurs. Fertilization of the sacred tree, a motif borrowed from Assyria, is a common theme, as is an individual standing before a seated divinity. Bronze plaques with religious themes must have something to do with a popular form of religion, albeit very obscure. Circular grooves cut into rocks on high places and elsewhere are associated with the Urartians and also speak for an aspect of religious practice that we know almost nothing about.

DEMISE

When and why did Biainili cease to exist? What enemy torched and pillaged its mighty citadels?

We do not know the answer with any precision. Urartu as a geographical designation, continues to be used for some time, but there is no firm evidence that it was a political entity after 639 BC. According to the testimony of Herodotus, who had never heard of Urartu or Biainili, the Medes established their border with the kingdom of Lydia on the Halys River (Kızılırmak) in 585 BC

344

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

after 5 years of war, and it seems unlikely that they would have left an Urartian state in their rear. One school of thought is that the Medes, who doubtless inherited Biainili’s territory at some point, were the ones who administered the final blow to the kingdom, a few years before 590. In support of this late date, there is a reference in the book of Jeremiah, ostensibly dating to 594 BC, in which the kings of Ararat, along with the Scythians, are invoked as a force which will punish Babylon.53 Contrariwise, we cannot be certain any Urartian document or royal building activity dates after the reign of Rusa son of Argishti, and it is hard to see how Biainili could have been an active concern for five or six decades without leaving some clear archaeological evidence of its existence.54 If the kingdom was destroyed shortly after the middle of the 7th century, as seems likely, it would help to explain why so little memory of it survived in later historical writing. This would mean that the Scythians were the agents of destruction, and the Medes inherited nothing but ruins when they took over the territory. In the 6th century certain individuals in Mesopotamia are said to be from Urashtu, which probably just means the north. The last formal reference to it as a place is by the Achaemenid Persian king Darius I, who mentions it in the Akkadian and Elamite versions of his great trilingual inscription at Behistun, but substitutes “Armenia” in its place in the Old Persian text.

The disappearance of Urartian culture was remarkably thorough. For the most part, Urartian sites were not re-occupied—particularly those created by Rusa, son of Argishti, in the final burst of construction. When the Greek historian Xenophon passed through Urartu’s erstwhile territory in 399 BC, there was little left for him to observe, and he gives no indication that he was aware that a great kingdom once existed here. A millennium or so later, the Armenian historian Moses Khorernatsi attributed the inscriptions at Van to the legendary Assyrian queen Semiramis, but he was getting his information from classical sources via Greece, not from any direct local transmission. The contrast with the Hittites, whose traditions could still be perceived five centuries after their empire collapsed, could not be stronger.

NOTES

1The consonant renderer as t in these variants and the word Urartu itself was actually the equivalent of a Semitic emphatic tet, which is normally transcribed as at with a dot under it. Since English doesn’t have this phoneme and symbols for it are absent in even the extended character sets of most word processing systems, we will follow the normal modern convention of ignoring the dot.

2Grayson 1987: 183.

3Grayson 1991: 21.

4Sevin 2001: 79.

5An overview of Early Iron Age sites in the Van area is provided by Belli and Konyar 2003.

6Sevin 1999: 163.

7Sevin and Kavaklı 1996: 53.

8Sevin 1999: 162.

9Grayson 1991: 288–293.

10Specific sources for this are summarized in Zimansky 1985: 48–50.

345

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

11Zimansky 1985: 48–76.

12As this book goes to press, a new, comprehensive edition of all Urartian of texts is being published by Mirjo Salvini. The new translations, in Italian, will be conveniently organized and indexed. Therefore we have not given references to specific Urartian texts in the obsolete German and Russian collections here.

13The end of Hasanlu IV, one of the more dramatic destruction levels in the ancient Near East, has been challenged on more than one occasion. It was originally dated to around 800 BC by its excavators, who have consistently defended that date (Dyson and Muscarella 1989) and whose arguments we find convincing. Burney and Lang 1971: 134, 145 suggest that the Urartian king might be Argishti I, which would put it a generation later. Others have opted for still later dates, and suggested that the Assyrian king Sargon II was responsible for it.

14A table presenting the campaigns in summary, with the figures from the booty lists is given by Zimansky 1985: 58.

15The most readily available English translation of this important document is still Luckenbill 1927: Vol 2, pp. 73–99, although more complete and up-to-date editions are in preparation.

16Salvini 1995: 84–89 discusses the letters in question.

17The site of Toprakkale, where the first excavations in Urartu were conducted in the 19th century AD, was long known to have been founded by a Rusa, but the Kes¸is¸ Göl stele, which records the fact, was broken and did not give his patronymic. Another fragmentary stele (Salvini 2002) from the same area, of the which the author is Rusa, son of Erimena, has now been recognized to join the Kes¸is¸ Göl stele, thanks to a duplicate which Salvini has subsequently discovered. Thus Rusa, son of Erimena, claimed to be the founder of Rusahinili (Toprakkale) and the site was a going concern in the time Rusa, son of Argishti, who therefore must come later, barring the possibility of a refounding.

18Burney and Lang 1971: 158.

19Zimansky 2005: 235.

20Interestingly, it lists many places we have never heard of, but fails to mention any of the great projects like Bastam, Karmir Blur and Kefkalesi which are known from his other inscriptions. For the inscription, see Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 253–270.

21This is assuming that Rusa, son of Erimena, ruled in the 8th century, and not in the obscure period after Rusa, son of Argishti. In addition to the evidence on the founding of Toprakkale (Rusahinili before Mt. Qilbani) noted above, the style of the art associated with Rusa son Erimena would argue for the earlier date (Seidl 2004: 124).

22For a long time this was read lúA.NIN, which could be interpreted as “son of the lady” and was understood as “crown prince.” The names of people bearing this title have names like Sarduri and Rusa, so this was not unreasonable. However, it is now clear that the sign for “lady” was misread, and no literal meaning comes from the new understanding of the sign. Seals of these officials regularly show winged genii fertilizing a sacred tree, and often a winged centaur on the stamping end. See Hellwag 2005 for a discussion of the reading and recognition that the holders of the title are of the royal family, but her conclusion that it means “minister of water” seems strained.

23Salvini 1995: 111.

24Zimansky 1995.

25For a plan of the area, see Salvini 1995: 144.

26For depictions on bronze belts, see Seidl 2004: 145–147. A bronze model of part of a facade shows two stories above the top of a monumental door (Wartke 1993: Taf. 28; van Loon 1966: plate 20).

27Belli 1999: 16–28.

28Ambiguities of the cuneiform script would also allow the reading “Iubsha” for this deity, which is the reading favored by Salvini 1995: 61.

29A full description of the finds at Ayanis up to 1998 may be found in Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001. In the seasons of excavations since then, many more luxury items have been found in the storerooms of

346

A K I N G D O M O F F O R T R E S S E S

the temple complex, including numerous bronzes, bullae and seals, but no further monumental inscriptions have been discovered.

30Zimansky 2005.

31Piotrovsky 1969: 140 mentions 400 pithoi but gives the capacity as only 9000 gallons, which can hardly be correct. Wartke 1993: 87 reports the capacity as 400,000 liters, which accords better with the size of the pithoi.

32Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 308–311.

33Seidl 2004: 207.

34Drawings of a reconstruction, see Seidl 2004: 62–63.

35Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 186.

36Seidl 2004: 133–197.

37Reproduced by Wartke 1993: 56.

38Wartke 1993: Taf. 59.

39Kleiss 1988: Taf. 31.

40Kleiss 1988: Taf. 22–27.

41Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 327.

42A photograph of the one known tablet written in hieroglyphs, from Toprakkale, is given by Wartke 1993: Taf. 86.

43For an up-to-date sketch of Urartian grammar, see Wilhelm 2008.

44Salvini 1989.

45His name appears so frequently in royal dedications and campaign inscriptions that in the early days of modern scholarship on Urartu it was erroneously believed that the Urartians called themselves the “Children of Haldi” and the Khaldaioi, a people of eastern Anatolia mentioned by Xenophon and other Greeks, were thought to retain some connection with the erstwhile state by taking the name of its chief deity. The derived terms Chaldians, Chaldian, etc., now quite obsolete, are still common enough in the literature on Urartu to cause confusion with the Chaldaeans of Babylonia, who have nothing to with Urartu.

46Salvini 1995: 183–184.

47Belli 1999: 34–65.

48For many years it was believed by some scholars that a sˇuri was a chariot while others saw it as a sword. The dispute was settled by the discovery of a 1-m long ceremonial blade with an inscription on the handle identifying it as a sˇuri. See Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 172, 277.

49The other temple at Çavus¸tepe has no inscription. Although it is referred to as the Haldi temple by its excavator, this is simply an assumption by default. The great majority of dedicatory inscriptions for temples in Urartu, most of which have been separated from their archaeological context, are to Haldi.

50The ground plans of these buildings are well known thanks to the survival of their stone foundations, but how tall the buildings were and how their roofs were constructed remain controversial. The upper portions of the walls were made of mud brick, which has not survive any higher than the 3 m preserved at Ayanis. The thickness of the walls and the fact that the Urartian term used for this temple, susi, was apparently translated as “tower” in Akkadian would argue for a very tall building. It is likely that the doorways had the same proportions as the false doors of rock carvings like Meher Kapısı, which would also argue for height. On the other hand the Assyrian relief depicting the of the sack of Haldi temple at Musasir shows a building that is not particularly tall. Was the Musasir temple an Urartian susi? The bronzes found at Ayanis show that it was certainly decorated in the same manner.

51Çilingirog˘ lu and Salvini 2001: 57–59.

52There have been suggested reconstructions of this based on the finds of bronze furniture attachments that came out of various 19th-century excavations.

53Jer 51: 27

54Kroll 1984 makes the case for this earlier end to Urartu, which is now the prevailing scholarly view.

347