- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

PA L A E O L I T H I C A N D E P I PA L A E O L I T H I C

methods. The tools were then modified even further into a range of shapes and edge type by retouch. So while the assemblages from both periods show diversity, this feature was determined at the commencement of the reduction process in the Lower Palaeolithic and at the end in the Middle Palaeolithic.

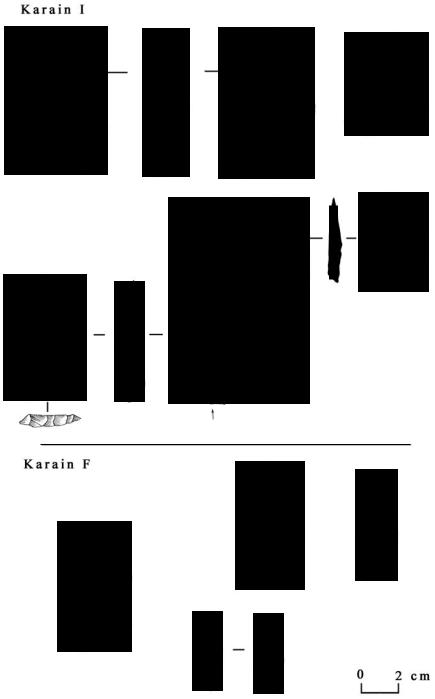

MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

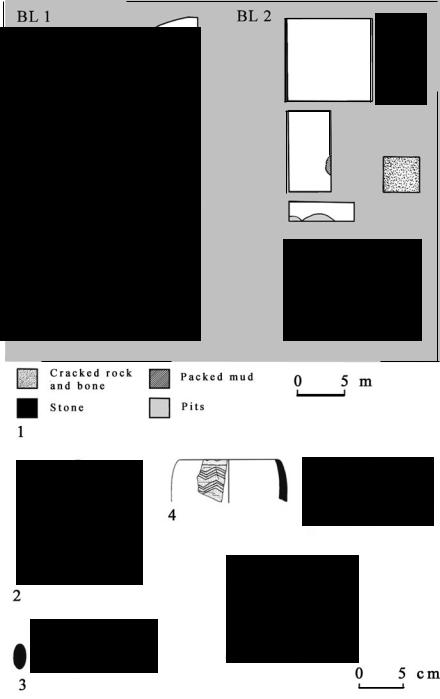

The most important Middle Palaeolithic sequence in Anatolia is Karain Cave. In Layer F, significant technological changes and procurement patterns appear that clearly link the upper deposits (F–I) with the Mousterian industry (Figure 2.5). Among the new traits are the use of the Levallois technique that replaces abrupt retouch, the appearance of Mousterian points, and the preference for sidescrapers over denticulates and notched tools. Tools were modified and used in a more intense fashion, with evidence for the complete reduction of cores. There is also a greater variety of raw materials. Although the stone used was still local, the occupants of the cave went further afield for raw material to produce large flakes. Towards the end of this Middle Palaeolithic deposit, in Layer I, tools were quite small and the assemblage as a whole was not so Levallois in character; in addition to radiolarites, sandstone and quartzite were utilized for the first time. Overall, the technique employed by the knappers of Karain and the shapes of the tools they produced are redolent of the Zagros cave sites rather than the Levantine Mousterian. The small leaf-shaped points from layers H–I also resemble the bifacially worked tools from the Balkans and central Europe.29 Moreover, the amount of debitage in the sequence suggests that stone tool production in the Middle Palaeolithic was now an indoor activity. Kocapınar, BeldibiKumbucag˘ ı and Kaletepe Deresi 3 have comparable Mousterian assemblages, although not as extensive, or as well studied, as yet.30

A group of fossil hominids was discovered in Karain Layer F (geological unit III.2). Several distinguishing traits, such as a pronouncedly receding chin and the frontal disposition of the incisors, suggest they belong to Neanderthals. This identification is potentially very significant for just like the Denizli Homo erectus remains it sheds light on early migrations. The Karain fossils not only attest the presence of Neanderthals in Anatolia around 250,000–200,000 years ago, well before they reached the Levant (123,000–120,000 years ago), but also suggest that they migrated from Europe when the glaciers had reached their maximum extent during the Oder stage (oxygen isotope stage 8).

Nearly 20,000 mammalian bone fragments were recovered, but only about 15% could be identified. Even so, the Karain faunal record is noteworthy. Four taphonomic groups could be distinguished: (a) consumption refuse—animals that were hunted and transported back to the cave by humans, including goats and sheep (dominant throughout the sequence), various deer (fallow, roes and red), and wild boar, aurochs, and equids; (b) workshop debris—animals (hippopotami and elephants, ovicaprine horns, and deer antlers) prized for their bones, which were carved into objects, rather than for nutritional value; (c) competitors—carnivores such as bears,

19

PA L A E O L I T H I C A N D E P I PA L A E O L I T H I C

wolves, foxes, and hyenas, which also used the cave for shelter; (d) intrusions—animals (small birds, hares, hedgehogs among others) that could have been transported to the cave by predators and raptors. While a few animals have an ambiguous position, whether as prey of human or animal predators, this analysis does show some clear patterns. One thing that is clear is that like at Yarımburgaz before it, the occupants at Karain shared their abode with wild animals. At Kaletepe Deresi 3, a mandible and two molars of a primitive form of equid are worth noting.

UPPER PALAEOLITHIC AND EPIPALAEOLITHIC (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

At the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic (ca. 45,000–40,000 BC), stone tool industries in Near East display an important element. They retain archaic Levallois features, but also embrace the production of blades that were struck off prismatic cores. In Anatolia, representation of the initial Upper Palaeolithic is scant. There are fewer sites ascribed to this period than the better known Lower and Middle Palaeolithic, and the subsequent Epipalaeolithic (or late Upper Palaeolithic) when these blade technologies were replaced by microliths. While this situation may reflect a general research bias in the field, this cannot explain the lack of evidence in the intensely surveyed regions around Marmara and in the southeastern region. More likely is that Anatolia, like Greece, was sparsely settled in the initial Upper Palaeolithic. This circumstance stands in sharp contrast to developments in the northern Balkans, the Caucasus, the Zagros region, and the southern Levant where occupation between the Upper Palaeolithic and Neolithic reveals no major gaps.

Presently, Uçag˘ ılı and Kanal caves both located near the Mediterranean shore of the Hatay province, and close to the mouth of the Orontes River, offer the best evidence for the early Upper Palaeolithic. Uçag˘ ılı is a collapsed cave investigated some 15 years ago. Three main cavities were opened, with Locus 2 yielding the most detailed deposit (1.5 m) which comprised four layers. There is general agreement that the lithic industry resembles those in the Levant, especially Lebanon (Figure 2.6). Two different assemblages are represented at Uçag˘ ılı: The earliest deposit has endscrapers, burins and retouched blades like those found at Ksar Akil (Lebanon), whereas in the higher levels pointed blades produced through the bipolar technique are conspicuous and are again redolent of tools from Ksar Akil and also the Antelias shelter near Beirut. Accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) places the earliest levels between 41,000 and 43,000 years ago, and the latest range from 28,000 to 33,000 years BC. The Kanal assemblage also has strong southern connections. Both the Uçag˘ ılı and Kanal assemblages were produced from high-grade flint in the form of pebbles; the white cortex suggests they were procured from a source as nodules rather than from the sea shore. Blades predominate and can be retouched and unretouched, although flakes were still produced; the ratio is about 2:1. Generally broad, most blades were turned into endscrapers with a facetted platform and a pronounced bulb of percussion indicative of a hard hammer. This variety of lithics has generated discussion on nomenclature. The excavators refer to the Uçag˘ ılı tools as Aurignacian, using the number of flat endscrapers as a guide, though

21

PA L A E O L I T H I C A N D E P I PA L A E O L I T H I C

others prefer Ahmarian because of the high proportion of retouched and pointed blades termed el-Wad points.31 But there were differences between the Hatay sites and other initial Upper Palaeolithic sites around the east Mediterranean, namely the absence of certain key types, including Emireh and Umm et-Tlel points.32

In addition to stone, tools were manufactured from bone, including square-sectioned points found in the earliest levels. Judging from the quantity of modified shell remains, it is clear that the inhabitants at Uçag˘ ılı were fond of personal ornaments.33 Together with those from KsarAkil, the Uçag˘ ılı beads and pendants made from various marine gastropods comprise the earliest evidence for jewellery in the Near East, and are comparable in date to similar objects from Africa and eastern Europe. This widespread used of personal ornaments in the Upper Palaeolithic points to the emergence of external symbolic human behavior. Whereas wearing jewellery may not represent a fundamental leap in human cognition, it nonetheless represents another stage of communication expressed through body decoration. Uçag˘ ılı has also yielded a rich sample of animal bones, mostly herbivores (wild goats, and fallow and roe deer), with some game birds and tortoises.34

Evidence for the end of the Palaeolithic, or Epipalaeolithic, is found across much of Anatolia, but the best evidence for the early stages again comes from the warm Mediterranean coast and the southeastern region. Near Antalya we have a cluster of caves—Beldibi, Belbas¸ı, Karain B, and especially Öküzini—that offer a picture of life towards the end of the Ice Age.35 At the commencement of the earliest phase at Öküzini (ca. 17,800 BC), we witness further changes in lithic industries. Initially, the blank blades were modified into endscrapers, burins, and perforators that bear some resemblances to elements from the Kebaran tradition. In Layer 3, the narrow blades are snapped into microlithic tools (triangles, trapezes, lunates, and microburins), and later still (10,500 BC) the tools became even smaller, with cores now quite irregular. The tool kit at the very end of the Pleistocene also had a considerable number of awls, needles, and spatulas carved from bone, making it quite diversified. Moreover, the presence of grinding stones in the earliest levels points to emergence of intensive exploitation of plant foods. Faunal remains at Öküzini also show shifts in hunting patterns. Ovicaprines (mostly goats and some sheep) predominate throughout the sequence, but fallow deer and other forest animals increase to 40% of the sample in the uppermost deposits of the Pleistocene.

While the Epipalaeolithic along the Mediterranean littoral has affinities with the traditions in the southern Levant, some have argued that elsewhere in Anatolia it appears to be home grown.36 Likewise this coastal region lies outside the “nuclear zone” of wild cereals where the first experiments with agriculture occurred in the eighth millennium BC. These observations are rather significant in terms of their developments that marked the Neolithic. As the focus of settlement shifted towards the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, the Mediterranean coast of Anatolia, like those of Syria and Lebanon, was abandoned and resettled only much later at Mersin and other sites.

In the southeast, a number of groups began to change their behavior in a remarkable way. For the first time in Anatolia, they built houses and lived in them year round. We will deal with this

23

PA L A E O L I T H I C A N D E P I PA L A E O L I T H I C

fundamental shift in settlement organization more fully in the next chapter. Whether one ascribes these settlements to the Epipalaeolithic or the early Pre-Pottery Neolithic A is a moot point, given that the boundary between the two periods is still quite blurred. Nevertheless, the earliest sedentary communities have been identified at Hallan Çemi, Demirköy, Körtik Tepe and the earliest level at Çayönü.37 In central Anatolia, we have the mound at Pınarbas¸ı, which although dated around 8500–8000 BC, has a microlithic assemblage of stone tools that is typical of the very end of the Epipalaeolithic.38

At Hallan Çemi calibrated radiocarbon readings stretch back to the end of the 11th millennium BC, making it roughly comparable in date to Jerf el Ahmar and the earliest occupation at

Abu Hureyra 1 in Syria. The earliest dwellings at Hallan Çemi (Level 3) were stone built, C shaped and no more than 2 m in diameter.39 Of the four structures completely exposed in Level 2, three were well paved with sandstone slabs, and of these, one was large (about 4 m in diameter) and centered by a small, plastered basin (Figure 2.7). Judging by their sturdy construction (sandstone slabs), size (up to ca. 5–6 m in diameter), and installation (semicircular stone bench), the four buildings in the uppermost level appear to have served a public function rather than a domestic role. Similar round huts have been found at Çayönü (subphase 1), where they were partly sunken into the ground.40 Built with walls of reed or wattle and mud plaster, over time these small huts gradually assumed an oval shape. In these earliest levels at Çayönü, the deceased were buried in pits dug in open spaces or under the floor of the huts, in a tightly flexed position, accompanied only by a few pieces of ochre.

Both settlements reflect the emergence of community planning and a new sense of social awareness expressed through the public domain. At Hallan Çemi houses and other features, including low, round, plastered platforms, define a large central open area about 15 m across. The large amount of animal bone and fire-cracked stones found within them have been interpreted as the remains of communal feasting. At Çayönü open spaces were used for storage, stone knapping and dumping rubbish, possibly the remnants of feasting, too.41 Chlorite and limestone bowls finely ornamented with geometric and naturalistic designs from Hallan Çemi and Körtik Tepe, and a range of pestles with sculpted handles (Figures 2.7 and 2.8), comparable to those further south at Nemrik 9 and Tell Magzalia, were part of the paraphernalia used to prepare food for public consumption.42

As the focus of daily activities, these houses of the late Epipalaeolithic were also imbued with symbolic connotations that reflected the new circumstances of their builders. Whether it is the sense of settlement planning, suggesting some sort of social control, or the internal organization of space that becomes more apparent a little later, the emphasis placed on the house and settlement is clear. Communities were not only on the cusp of domesticating food resources, but they also experimented with new modes of social arrangement. This change in the social cohesion of sedentary groups was reflected later in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic by exuberant symbolism, but its roots are to be found in these earliest formative villages. These groups of circular hut-like structures, then, had an impact on the development of communal life that went far beyond their simple constructional technique.

24