- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

P R E - P O T T E R Y N E O L I T H I C

occurred frequently. A few fragments of wall plaster suggest that above the dado, walls were covered with a cream colored plaster and painted with red designs. House furnishings were few, including a low raised platform probably used to elevate grindstones and a cupboard—one in Level VI was fully enclosed and items were retrieved through a couple of small holes. Hearths and ovens were situated in the courtyard and like floors also had a base of pebbles; a mud brick kerb defined their edge.

Ritual, art, and temples

Southeastern Anatolia

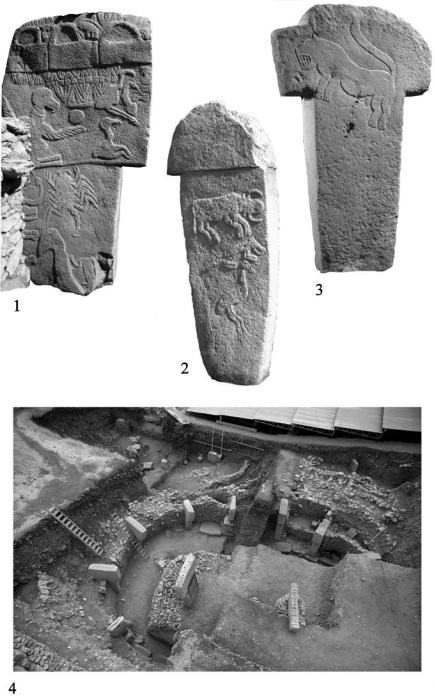

In recent years, the spectacular discoveries at Göbekli Tepe (9600–8000 BC) and Nevalı Çori (8600–7900 BC), perched in the lower rocky slopes of the Taurus Mountains, overlooking the lowlands of Urfa, have prompted a major upheaval in our understanding of ritual practice in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic. In the first instance, they have articulated in a superb manner the emergence and gradual elaboration of special (nondomestic) buildings built by communities of sedentary hunter-gatherers. We knew about the existence of public buildings from the earlier excavations at Çayönü, to be sure, but the date, preservation and monumentality of buildings uncovered at these Urfa sites have ushered in another level of complexity, not least of which is the notion, in the case of Göbekli, of a special ritual site serving a region. Whereas at Nevalı Çori both houses and temples are located within proximity of each other, Göbekli has only temples. Its lowest sequence, Level III, is represented by a series of stone-built circular structures up to 20 m in diameter (Figures 3.7 and 3.8) that are presently the earliest temples on earth.66 Monumental size, T-shaped pillars (some reaching a height of 5 m), benches running along the wall, and the use of sculpture, as integral architectural traits, are their distinguishing features. The pillars vary in size: the two largest are positioned in the centre, whereas a series of smaller ones are embedded into a bench. Their date in the second half of the 10th millennium BC makes them roughly contemporary with Qermez Dere (north Iraq) and Jerf el Ahmar (Syria), which are seen as the antecedents. In Level II, the Göbekli temples are rectilinear, although they still retain the other attributes.

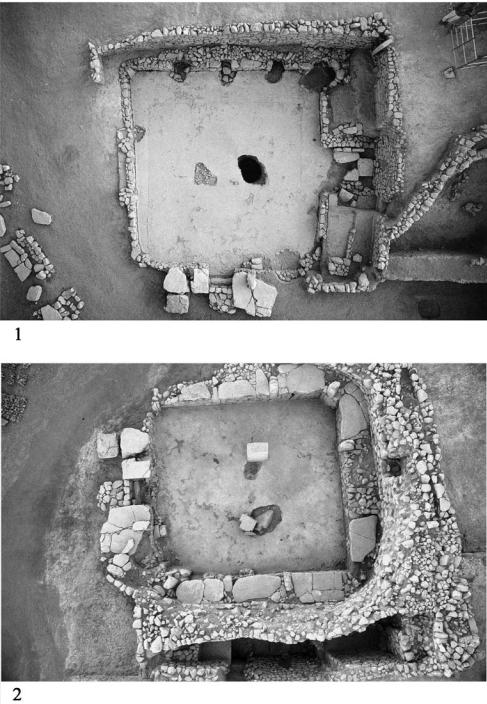

The cult buildings at Nevalı Çori are no less fascinating. There, excavations revealed a squarish building in Level II that clearly had a special purpose (Figure 3.9).67 Built of stone and whitewashed, it measured 13.90 by 13.50 m. Thirteen monolithic pillars with T-shaped capitals were set into a wide bench that ran along the interior wall. Two similar pillars had been presumably set at the centre of the paved flooring. Other features include a podium, which the excavators believe contained a cult statue, and a niche. Discarded fragments of sculpture from the earliest cult building that did not survive were found embedded within the structure. Its successor, Temple III, was smaller in size, having been built directly within the walls of its predecessor. Its plan and features remained basically the same with the exception of the two central pillars that

57

P R E - P O T T E R Y N E O L I T H I C

Figure 3.7 Plan of Göbekli Tepe showing the plans of the circular (Level III) and rectilinear (Level II) temples (adapted from Schmidt 2007)

58

P R E - P O T T E R Y N E O L I T H I C

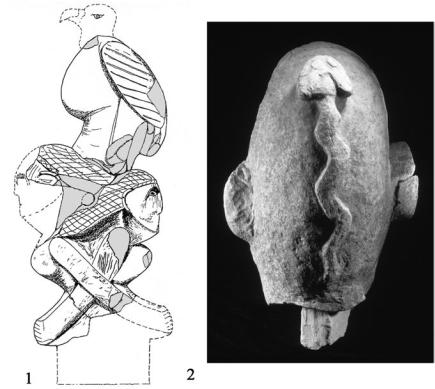

are now decorated with two arms holding hands. At this time a larger than life-size limestone head, bald with snake attached to its back, was reused as building material (Figure 3.10: 2). Indeed, with one exception, all 11 pieces of sculpture, largely human-animal compositions, were found in secondary positions. Whether the intention was apotropaic, or whether the sculpture was ritually broken, or simply had a utilitarian function as another building block is difficult to say.

Another distinguishing feature of these Pre-Pottery Neolithic cult buildings is their powerful imagery. At Göbekli, the T-shaped pillars are richly decorated with low relief art that is predominantly animalistic, featuring rampant lions, wild cattle (aurochs), foxes standing on their hind legs, wild donkeys and pigs, birds of prey, cranes, scorpions and snakes among other creatures (Figure 3.8). These figures are portrayed individually, or grouped; sometimes they are empanelled between linear geometric patterns. On one pillar, a net pattern forms the background of a bird scene, as if to show capture. There is no reference here to domestic animals and remnants of domesticated plants and animals have not been recovered from Göbekli. Here a community still very firmly ensconced in the hunt created the striking imagery and monumentality. Perhaps the most spectacular composition is found on pillar no. 43 with its diverse repertoire of motifs and animals figures (Figure 3.8: 1). Dominating the central area is a bird, its curved beak and folds around the neck indicative of a vulture. Above its left wing is a circle and further to the right is another smaller bird curiously depicted as if to fit the space. Above this bird is yet another, possibly an ibis, to judge by its long legs. Three rather strange box-like objects with semi-circular handles each associated with a small depiction of a creature—its “animal determinative”—are juxtaposed along the top of the pillar. In the lower scene is a clearly depicted scorpion positioned above a bird and beside a fox. Finally, in the bottom right-hand corner, is a most interesting depiction—a headless male clearly identifiable by his erect penis. Although this figure is diminutive compared to the animals, it carries a strong stylistic resonance of the floating, headless humans depicted on the so-called vulture painting at Çatalhöyük, which we will deal with in the next chapter. Ithyphallic human statues and the depiction of male genitalia on all animal mammals further emphasize the male sex. An exception to this is the sexually explicit figure of a woman with legs akimbo carved on the floor of one of the temples. The depiction of cranes at Göbekli is particularly interesting. Whereas their torso is easily identifiable, they appear to have thick, clumsy legs with knees bent forward rather than back. It has been suggested that these are meant to show human legs, implying that they represent either a hybrid creature, or a human dressed as a crane. The extent of this monumental Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture is only just becoming apparent, now that we know what to look for. A carved pillar found on Nemrut Dag˘ , in the Adıyaman province, suggests that it could be fairly extensive south of the Taurus.68

Sculpture from Nevalı Çori is invariably worked in soft limestone and shaped with flint implements.69 Meaning was often conveyed through hybrid creatures combining animal and human features—snake-men and bird-women. Moreover, arrangements are reminiscent of totem poles, with figures superimposed and melded into each other. One fragment of bird sculpture is such piece. Most likely belonging to a much taller original, it shows the bird

61

P R E - P O T T E R Y N E O L I T H I C

dark inside. So the surrounding physical conditions, as with any sacred space, no doubt heightened the emotional experiences of participants. More importantly, the temples themselves were clearly public buildings and their public display no doubt promoted communality.70 Group cohesion of this type may well have served to bond communities like Göbekli and Nevalı Çori— neither nomadic hunters nor sedentary farmers—and assisted them in adjusting to their new circumstances. Then we have the explosion of highly visual symbolism. This overt imagery is no doubt linked to the importance placed on ritual in social life. These communities needed to explain their new world order and they did so through symbolism. In fact, as the wild, natural world was being controlled, so too was society. That is, vibrant symbolism was, as Marc

Verhoeven has aptly suggested, “an expression of the desire to control ritual behavior and the supernatural world, in order to control the human world.”71

But how can we explain the preponderance of animal imagery, explicitly wild animals and, in particular, birds? Here we need to recall what we said about ritual and rock art. One of the similarities between the late Palaeolithic rock art sites and the Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites is the prevalence of an animalistic iconography. The main difference is the type of settlements—one group comprises natural open-air sites or caves, whereas at Göbekli and Nevalı Çori we have built environments. I would propose that another similarity between the two periods is the prominent role played by shamanism in ritual. As we have seen, the last stage of a trance is often connected to a hallucinogenic transformation into an animal, especially birds, because experiencing a “cosmic flight” is one of the most common elements of shaman’s altered state of consciousness. This association between humans and birds, and the concept of “taking flight,” is well illustrated in a documentary film of the Kwakiutl Indians, who live along the British Columbia coast, made in 1914 by Edward Curtis, an American frontier photographer.72 In one scene Thunderbird, a human dressed as a bird, is seen standing at the prow of the war canoe flapping his wings. Although one should not imply that Curtis’ documentary portrays shamanic behavior, it nonetheless vividly captures the human-bird linkage in animation. It is not unreasonable, then, to suggest that the purpose of the reliefs depicted at Nevalı Çori and

Göbekli was to capture the presence of this or that animal.

Another Pre-Pottery Neolithic practice should be mentioned here, namely the seemingly unusual custom of “burying” a building at the end of its lifespan. This practice of deliberately filling a room with soil or mud bricks, as if to accord a structure humanizing qualities, was first identified by David French at the Chalcolithic site of Can Hasan, and has since been detected elsewhere.73 At Çayönü two special buildings of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period are noteworthy: The Flagstone (FA) Building and the Skull (BM1) Building, which in part retained the traditional oval plan (Figure 3.5: 1–2). Both were buttressed, but only partially preserved.74 The Flagstone structure had a floor of large limestone slabs and three undecorated stele that were broken before it was “buried.” Monumental standing stones were probably also used in the Skull Building whose association with death is found in two shallow pits that contained multiple burials sealed by its earthen floor.

It was in the cobble-paved subphase (the third evolutionary stage) that the Skull Building

63