- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

Regional variations

Eastern Anatolia

In the Early Chalcolithic period much of the territory south of the Taurus was associated with the Halaf tradition that stemmed from Upper Mesopotamia. In the Near East this was a period of cultural integration, despite regional variations, that stretched over eight centuries (ca. 6000– 5200 BC). Defined by a sophisticated assemblage of painted pottery, occasionally executed in polychrome and ornamented with geometric and naturalistic motifs, this complex had a farflung distribution, extending from the Upper Euphrates region around Malatya-Elazıg˘ to the middle of Mesopotamia in Syria and Iraq, and incorporating the plains of Cilicia and Amuq, the southern part of the Lake Van region, and the western borders of Iran fringing the Zagros mountains. Other cultural indicators are distinctive circular architecture, an organizational system that used seals, and an elaborate craft production especially well reflected in worked obsidian that was in great demand, and part of a long-distance trading network. Although these southern interconnections were pervasive throughout southeast Anatolia, they appear for the most part to have been more directional than uniform.

Of paramount significance is the new evidence from the site of Domuztepe, in Kahraman Maras¸, a huge settlement of 20 hectares, making it one of the largest prehistoric sites of the Near East.122 Since 1995 three main cultural phases have been discerned in several operations: Phase A-1 (Late Halaf, ca. 4750–4500 BC), and Phases A-2 (formerly, Post-Halaf A) and A-3 (formerly, Post-Halaf B), covering about 4500–4300 BC. Several examples of round structures with a rectilinear entrance passage were exposed—the classic and somewhat inaptly termed tholoi houses—that were built with either rammed earth or mud bricks. Rectangular mud brick buildings continue throughout this phase into the Ubaid. This combination of “keyhole” and rectilinear architecture is also attested at Çavı Tarlası, near Hassek Höyük, and Kurban Höyük.123

It is the so-called Death Pit of Phase A-2, however, that warrants special attention. This seemingly simple arrangement, an earthen grave approximately 3 m in diameter and 1.5m deep, belies a complex funerary deposit and associated ritual feasting.124 Essentially, the Death Pit is the site of a mass burial, containing layers the disarticulated bones of at least 40 individuals and a large number of animals, mixed with ash, broken pottery, and other artefacts. The sequence of deposition is rather important. First, a subrectangular pit was dug and the soil dumped along the southern edge, creating a bank. Then came two deposits of animal bones (Fill A and B), found interleaved with layers of silt. The nature of the silting, caused by rain or possibly the deliberate pouring of a liquid, suggests a relatively short interval. The third and final stage of the process saw two other fills deposited on either side of the bank of earth. Fill C, laid on top of the first animal remains, consisted largely of a hard-packed matrix of earth, ash, human, and animal bones that rose above the original level of the pit, forming what the excavators describe as a raised hollow. This might suggest that the original dimensions of the pit were too small and that

125

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

the fill had been literally packed in (by stomping?). The adjacent Fill D contained few or no human bones, and apparently comprised mostly domestic refuse, including animal bones that were more fragmented that those recovered from Fill C.

The patterns of animal bones as determined by age, sex and species are also telling.125 Domestic animals—cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and some dogs—are in the majority, with only a very small quantity of wild taxa cuts of meat thrown in the pit, among them those of gazelle, equid, deer, and bear. Whereas the range of animals from the Death Pit tallies with that recovered from the settlement, the relative proportions are markedly different. Most notable are cattle bones, which are overrepresented in the pit compared to the domestic quarters, and pig that are significantly fewer. This emphasis on valuable animals for ritual consumption is also reflected in the high percentage of adult female cattle and sheep/goat. While there is no evidence that the animals were sacrificed in any special manner, in so far as the method of butchery did not differ greatly between the two areas, the animal bones recovered from the Death Pit were more complete and articulated. This might reflect not only different taphonomic processes through better preservation conditions, but also different cooking techniques and modes of eating. It seems that participants of the feast may not have been as fussy about consuming all the meat and marrow, as they were accustomed to do.

Mersin certainly fell under the influence of the Halaf in Levels XIX–XVII, which enriched the local painted pottery, but Western Cilicia was on the fringe of this tradition. The settlement plan is still rather vague, though a large rectangular structure and a circular outdoor oven, both stone based, can be discerned. It is not until we reach Mersin XVI that we have a coherent settlement plan. Garstang exposed part of a carefully planned fortified village surrounded by a thick fortification wall, with two projecting towers flanking the gateway, which led down to the river, or to the central courtyard. Abutting the interior of the circuit wall is a row of tightly packed squarish rooms, each with its own enclosed courtyard. Slit windows allowed light into the rooms, which were otherwise furnished with standard domestic equipment—benches, hearths, grinding stones, and so on.

Along the Turkish Euphrates and its tributaries Halaf ceramics have been found at Tülintepe, Korucutepe, and Çayboyu in the Keban region, and further down at Samsat and nearby sites.126 In the Diyarbakır region it occurs at Gerikihacıyan, and beyond at Tilkitepe and Yılantas¸ near Van.127 Painted and plain Halaf pottery are represented in Amuq C and D, whereas further north we have Domuztepe, and west there is Mersin, which despite local painted wares has strong links with Amuq D. Halaf vessels have an orange to buff biscuit, and, when painted, designs are executed in red, orange, dark brown, or black. In the late period, bichromy was achieved by varying thicknesses of paint. A single thin layer of paint produced an orange effect, for instance, and a thicker layer produced dark brown. Rare are the splendid polychromatic designs, where white is used as a highlight. The artistry and technical competence of Halaf pottery improved through time, reaching the highest level of sophistication in the late period. Potters were fond of rich designs that were repetitive and minute. Bands or panels filled with an bewildering array of motifs—including pendant triangles, circles, stipples, fish scales, net patterns, wavy lines, and

126

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

zigzags, to mention a few—are rendered with precision and neatness, features that stand in sharp contrast to the bold and large patterns western Anatolian ceramics. The bull’s head, or bucranium, motif is the most representational design of the Halaf period. There is evidence to support the view that the naturalistic bucranium designs were earlier, and that they later became increasingly stylized until they were reduced to an abstract, geometric shape.

Some of the most intriguing painted sherds belong to a jar from Domuztepe that is decorated with a scene showing two-storied, gable-roofed buildings, separated by trees and pots. In the foreground, a chequered pattern, possibly matting, appears to support the field evidence that architecture at the site was constructed of various materials. On top of the structures are rows of long-necked birds. Apart from providing us with a vivid impression of buildings, these sherds are important from a technical perspective, attempting to show as they do several sides of a building on a flat two-dimensional surface. The fringe elements of the Halaf horizon are well attested at Mersin where black burnished wares ornamented with white-filled pointillé designs occasionally boast horned handles that are redolent of ceramics from the Konya Plain. These were associated with the local painted ware that extended south to Ras Shamra.

The Ubaid, a complex that originated in the plains of southern Mesopotamia, follows the Halaf. A northern variant of the Ubaid culture appears around 4500 BC in the area of Anatolia earlier occupied by Halaf communities. These northern traits that developed in the Tigris piedmont and eastern Jezirah are well documented at Tepe Gawra, and belong to the latest development of the Ubaid, which can be loosely ascribed to the Middle Chalcolithic.128 Trade was no doubt part of the continued contact with the south, and along the Turkish Euphrates we note a concerted effort to exploit natural resources in the Late Ubaid period. At Deg˘ irmentepe, the presence of foreign traditions is most apparent in the use of stamp seals that were used to mark merchandise in an evolving system of administration and accounting. The impressions of these stamp seals, the clay sealings (also known as bullae and cretulae), show a distinctive regional style with geometric motifs, horned animals, vultures, and human figures, possibly shamans.129 Nearby, Ubaid traits appear at Nors¸untepe, Korucutepe, and Tepecik. One of the distinctions of the Ubaid is pottery, both painted and monochrome, among which so-called Coba bowls, vessels with a scraped surface named after Sakçegözü (Coba Höyük), are the most common. Ubaid pottery is far more haphazardly painted than Halaf. Loose patterns of festoons, zigzags, and other linear designs are executed in a purplish-brown paint on clay often baked to greenish buff. Ubaid traits are found at Amuq E (Tell esh-Sheikh ware), Gedikli (near Sakçegözü), Mersin XV–XIIB and around Maras¸. At the other end of the Taurus, Ubaid traits occur at Tilkitepe and among the surface material from the Ag˘ rı region.

The central plateau

After Çatalhöyük East, material recovered from exploratory trenches and collected from the surface at Çatalhöyük West and the excavations at Can Hasan, near Karaman, provide the best

127

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

evidence for settlement in the central region. For the most part, Chalcolithic buildings at Can Hasan never used stone as a foundation course. According to David French, Can Hasan 3 represents a turning point in architecture at the site shown by the use of standardized mud bricks and the size and symmetry of the excavated building. Interestingly, however, he also notes “that the walls of Layer 3 had been deliberately constructed on the top of Layer 4 walls.”130 French surmises that this may have been for stability, but we have come across this tradition at Çatalhöyük, and it is tempting to consider this a carry over of a Neolithic practice that firmly connected people with place.

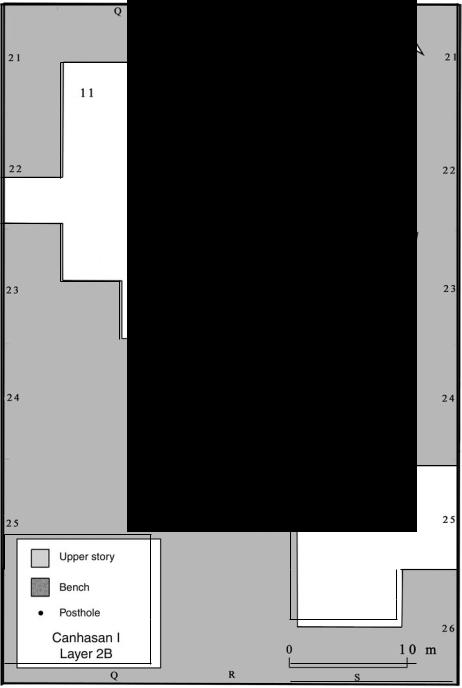

Level 2B has been ascribed as transitional between the Early and Middle Chalcolithic, whereas Level 2A is seen as fully developed Middle Chalcolithic, although its structures are fewer in number and poor in preservation compared with those in Level 2B. Again, we notice the enduring central Anatolian Neolithic tradition of tightly grouped independent structures without any intervening courts or alleyways (Figure 4.22). The avoidance to share a party wall is clear and deliberate. The best preserved building, Structure 3, whose walls stand over 3 m high, has an intact doorway linking the main room with the anteroom. Most rooms have a squarish plan, and each is well built, using mud bricks of uniform size (80 × 40 × 10 cm). Several internal buttresses strengthened the walls and created a series of niches, many of which were fitted with a bench. There is some evidence that walls were coated with white plaster, and fragments of red- on-white painted plaster suggest some rooms were ornamented with geometric patterns. All Level 2B structures appear to have had an upper story of sorts that would have created a staggered roofline, whereby the floor of the roof of the lower story was the floor of the upper. Entry to all the lower rooms was through the roof, which comprised closely set beams superimposed by a layer of branches and reeds laid perpendicular to the beams, and sealed, in turn, by clay and white plaster.131 Level 2A largely constitutes the rebuilding of a few 2B structures, but the standard of building techniques appears to have dropped.

The Late Chalcolithic settlement at Can Hasan Level 1 is poorly preserved, but it is clear that it had a completely different layout to the previous period. Open spaces (“courtyards”), not apparent in the Middle Chalcolithic, are now incorporated into the plan and fitted with ovens, bins, and partitions. Buildings appear to have been modified fairly frequently, perhaps because this part of the settlement was built on a slope at that time. Nonetheless, on the inside, houses were well maintained—walls were thickly coated with white plaster and the floors covered with hard white clay.

The ceramics of Can Hasan 2B began largely as a mixture of painted (red-on-cream wash) and burnished wares; vertical and horizontal rows of zigzag lines are the basic painted patterns.132 Gradually, the quality of both types improve, and the burnished fabrics (gray, redbrown and buff) have their surfaces both well polished and incised; in the last building level a new pottery type appears—white-slipped red ware with painted designs of simple horizontal lines and cross-hatched triangles executed in brown or black. Although the incised wares do not occur in Can Hasan 2A, the various painted and plain wares provide a link. But what distinguishes Can Hasan 2A are large jars elaborately decorated with polychrome designs of

128