- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

7

ANATOLIA’S EMPIRE

Hittite domination and the Late Bronze Age (1650–1200 BC)

The Hittites loom over all other peoples in the early history of Anatolia in their broad exercise of political power and lasting cultural impact. Uniting the disparate principalities of central Asia Minor, they created an empire which spilled off the Anatolian plateau into Syria and vied with Egypt, Mitanni, Babylonia, and Assyria as one of the great powers of the day. The Hittites are to be respected not only for their political and military accomplishments, which are awesome enough, but also for the richness of their artistic, literary, and historical tradition. They were a force in the cultural development of Anatolia whose impact was felt long after their empire collapsed at the end of the Bronze Age.

THE REDISCOVERY OF THE HITTITES

Modern recognition of the significance of the Hittites only dawned in the last quarter of the 19th century AD. The historians and geographers of ancient Greece appear to have had no notion that a great empire had once been ruled from the Anatolian plateau. Herodotus ascribed one Hittite monument on ground he knew well, the Karabel relief (Figure 7.1), to the Egyptian king Sesostris.1 While the Bible introduced the term “Hittite” to ancient and modern vocabularies, its testimony was composed in the aftermath of the Hittite Empire’s collapse and reflects two distinct concepts that are tied to the political and social conditions of the Iron Age. On the one hand, it lists Hittites among the aboriginal inhabitants of the promised land on an equal footing with the Girgashites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites.2 “Hittites” of this kind sold land to Abraham and married their daughters to Esau. A different concept seems to apply when the term “Hittite” was generally used for kingdoms of northern Syria. According to the most frequently cited passage in this regard, Ben-Hadad’s Syrian forces besieging Samaria

253

H I T T I T E D O M I N AT I O N A N D T H E L AT E B R O N Z E A G E

retreated in fear of an approaching army of the kings of the Hittites and the kings of the Egyptians which they believed the Israelites had hired.3 Such references make sense in terms of what we know of the Neo-Hittite principalities in northern Syria in the early first millennium BC.4 This picture began to change in the late 19th century. William Wright and A. H. Sayce began speaking of an “empire of the Hittites” in the early 1880s, basing their arguments for a major power on the distribution of monuments inscribed with a distinctive form of hieroglyphic writing. As Egyptian and Assyrian historical sources became available and intelligible to western scholars, this idea that the Hittites constituted a major power in the Late Bronze Age became irrefutable. The cuneiform documents of the 14th century BC Amarna archive, for example, showed that Egyptian kings corresponded with Hittite kings as if they were equals—a status indicating there must be something more to the Hittites than the Bible revealed. Until 1906, it was taken for granted that northern Syria was their homeland. In that year the northernmost site where “Hittite” hieroglyphs were then known, Bog˘ azköy, began to yield a flood of documentary information that was to revolutionize our conception of who the Hittites were and

the role their civilization played in the world of the second millennium BC.

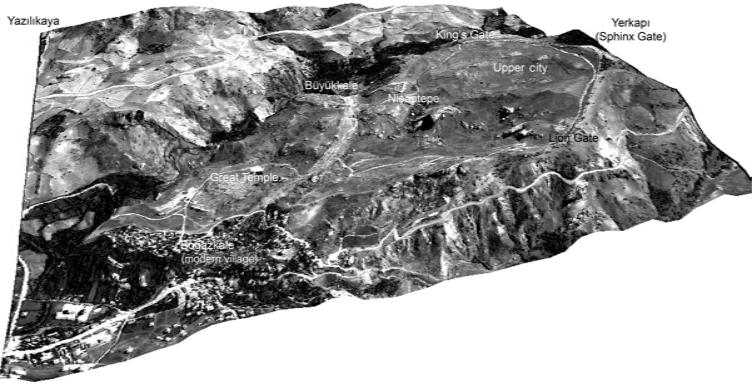

The extensive ruins beside the village of Bog˘ azköy, 154 km east of Ankara, were visited as early as 1834 by the explorer Charles Texier. The plans he later published correctly identified the surface remains of a very large building as a temple, now known as Temple I. He also published drawings of reliefs at the nearby group of rock outcrops known as Yazılıkaya, not rendering their unfamiliar style entirely successfully.5 He suggested the site was ancient Pteria, a city of the Medes which Herodotus said lay somewhere in this general vicinity. Over the next decades, several other individuals came to map these ruins, take squeezes of the above ground sculptures, and offer other hypotheses on their ancient identity and significance. The initial excavations were undertaken in 1893–94 by Ernest Chantre, who recovered the first cuneiform tablets from the site. But it was only when an expedition under Hugo Winckler and Theodor Makridi arrived on the scene in 1906 that the spectacular royal archives of the Hittite Empire were discovered.

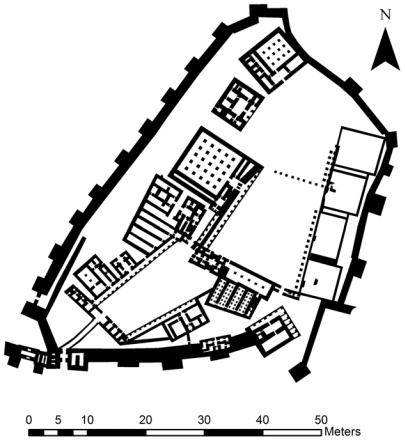

They actually found two major archives, which duplicate each other to a certain extent. One came from storerooms beside the ruins of the great temple that Texier had identified. The other came from atop a natural eminence known as Büyükkale (“large castle”) which the Hittites had fortified as their royal residence and seat of power, in short the imperial palace (Figures 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4). From these locations came thousands of tablets and tablet fragments covered with minute writing in cuneiform script. And what tablets! These were not mundane private and commercial documents of limited scope like the Cappadocian texts discussed in the previous chapter, but the intellectual tools required for the political and ideological maintenance of the empire: Treaties, annals, prayers, rituals, descriptions of festivals, myths, literature, and royal correspondence.

At the time of the initial discoveries, Winckler, who was an expert in ancient Near Eastern languages, could only partially understand what the tablets contained. Just as the Latin alphabet is used to write many modern languages, cuneiform was employed for many ancient Near

255

Hearth |

Hearth |

Hearth |

|

Hearth |

|

|

|

|

|

Hearth |

|

|

Hearth |

|

Hearth

Hearth

Figure 7.2 Topography of Bog˘ azköy, looking east

H I T T I T E D O M I N AT I O N A N D T H E L AT E B R O N Z E A G E

Figure 7.3 Büyükkale, looking north

Eastern ones, particularly at Bog˘ azköy. The conventions of the writing system provided some idea of what the texts were about even without an understanding of the language itself. For example, cuneiform includes many signs that stand for words (logograms) with consistent meanings in all languages, for example, signs for “king,” “palace,” “sun,” “god,” etc. There are also signs that indicate an associated word belongs to a certain category (determinatives), like pots, garments, place names, personal names, names of gods, and objects made out of wood. Most of the signs, however, are pronounced phonetically as syllables. These generally have standard sound values in all cuneiform writing, just as letters of the Latin alphabet do whether one is writing English, French, or Danish. Thus Winckler and his contemporaries could pronounce Hittite words even if their meanings were unknown. Moreover, a fair number of the Bog˘ azköy tablets were written in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the second millennium, which had been deciphered half a century earlier. With the historical information these contained, Winckler was soon able to draw up a preliminary king list and to establish that the ancient name of the city he was excavating was Hattusa,6 capital of the Hittites.

The majority of the Bog˘ azköy tablets, however, were written in Hittite,7 a language virtually unknown before Winckler’s discoveries. Winckler, who died in 1913, did not live to see its decipherment. The man who made the key breakthrough was Bedrich Hrozny, whom we encountered in the previous chapter as an excavator of Kültepe in search of Cappadocian texts

257