- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

H I T T I T E D O M I N AT I O N A N D T H E L AT E B R O N Z E A G E

Ramses II left a memorable account of the battle and claimed victory, the Hittite hold on Syria remained unshaken.

Muwatalli was succeeded by his son, who took the throne as Mursili (III), although he is better known to posterity by his Hurrian name, Urhi-Teshub. Muwatalli also had a very powerful brother, Hattusili, who was aggrieved to serve under Urhi-Teshub. Eventually he seized the throne himself, composing a detailed “apology” lambasting the iniquities of his nephew and putting forth his case for getting rid of him. It is one of the classics of Hittite royal propaganda. The capital was moved back to Hattusa, but another son of Muwatalli, Kurunta, was left to rule in Tarhuntassa with special privileges. This was to cause difficulties later. One of Hattusili’s accomplishments was to enter into a peace treaty with Egypt, and there was even a marriage between one of his daughters and the by now aged Ramses II. The last two kings of the Empire, Tudhaliya IV and Suppiluliuma II were nevertheless troubled by unrest both at home and in Syria. A rectangular bronze plate once hung by chains was discovered in the upper city of Bog˘ azköy, ceremonially buried near the Sphinx Gate.21 On it was a treaty between Tudhaliya and his cousin Kurunta. The reason the treaty was buried has recently become clear: Kurunta rebelled against the government in Hattusa and was, for a time, able to take over the Great Kingship himself. Tudhaliya was able to recover the crown, but it is clear the kingdom had suffered yet another crisis over succession. Tudhaliya had to weather one other great setback. Assyria, now a centralized state possessed of a ruthless war machine, had began making inroads into Hittite territories. At Nihriya, on the Euphrates, the Assyrian king inflicted a major defeat on Tudhaliya’s army, and thereafter the Hittite control of Syria was less secure. Tudhaliya had greater success in his conquest of Cyprus.

Suppiluliuma II, the last of the Great Kings to rule in Hattusa, also campaigned in Cyprus and was active in the Lukka lands. The circumstances under which the kingdom was lost and Hattusa destroyed are unknown, but were part of a general cataclysm that brought down civilizations all around the Mediterranean.

THE IMPERIAL CAPITAL

The archaeology of the Hittites in the Late Bronze Age is an archaeology of imperialism. It revolves around edifices devoted to defense and control; symbols of power and persuasion, and artefacts of cosmopolitan complexity. To discover its essence, one must begin at the center of command, the capital at Hattusa. This is one of the largest sites in the ancient Near East, covering an area of 167.7 ha and surrounded by a 6-km circuit of fortification wall.22 Archaeologically is it is a palimpsest of monuments of many periods, from an Early Bronze Age occupation to Iron Age remains belonging to a time when its status as a great capital had long been forgotten. It is to the Hittite Empire, however, that the vast majority of its surviving monuments belong, and its violent destruction at the beginning of the 12th century to which we owe so much of what we know about the material world of the Hittites.

266

H I T T I T E D O M I N AT I O N A N D T H E L AT E B R O N Z E A G E

The core of the site is the limestone eminence of Büyükkale (Figure 7.3). This forms a natural fortress overlooking a gorge and dominates more level ground to the northeast, where the earliest settlement area was located. Somewhat farther to the north lies the modern village of Bog˘ azkale, whose earlier name23 Bog˘ azköy, continues to be used as a designation of the whole archaeological complex. During the Old Kingdom, Büyükkale came to serve as the royal residence of the Hittite kings. Its natural defenses were enhanced by a perimeter wall with towers and buttresses, and access from the lower city was controlled through a single gateway approached by a ramp. In its final form in the 13th century, the palace consisted of a complex of monumental buildings grouped around a series of courtyards, increasingly secluded as one ascended. Only the stone foundations of these survive, leaving room for some uncertainty in how they are to be reconstructed. There were accommodations for palace personnel around the lower courtyard and the actual residence of the king was located in the highest, not far from the largest structure on the citadel, believed to be an audience hall with a grid of pillars supporting a roof over a large open space. The palace archives were discovered in three separate locations on the citadel.

The original settlement at Bog˘ azköy stretched northwestward over lower ground from the foot of Büyükkale. Houses were built there in the Early Bronze III period, and a karum of the trading colony period has been discovered a little farther to the northwest, beyond the ground on which the largest Hittite temple was later built.24 In the Old Kingdom this area was protected and joined to Büyükkale by a fortification wall. During the Empire the walled area of the city was vastly increased by the inclusion of the elevated ground to the south. The lower courses of these walls were built with massive, undressed stones and made more imposing by casemate construction, an older Anatolian tradition to be sure. There were towers at regular intervals and at least five major gates in the wall around the upper city. The latter were multiple chambered arched doorways flanked by towers and adjacent outer walls to control access from the outside.

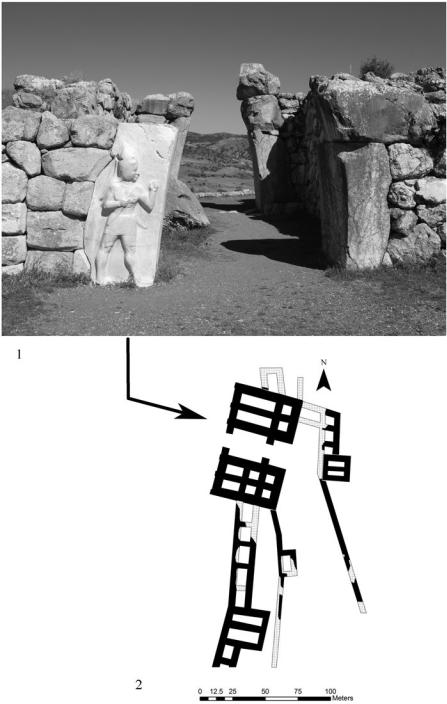

Although the enemies who destroyed Hattusa put some effort into destroying the protective sculptures that guarded these gates, some of them survive at three entrances to this upper city. The best preserved relief was found25 in the inner chamber of what is popularly known as the “King’s Gate” on the eastern side (Figure 7.6). This male26 figure, executed in such high relief that it allowed the sculptor to put the eye in natural perspective on the front of the face, rather than rendering it front view on a side view head as is customary in more shallow Hittite and Egyptian reliefs, is not, in fact, a king. He wears a horned crown, which is reserved for deities, and the Hittite Great King, unlike his Egyptian counterpart, was not god.27 Rank in the pantheon is also reflected by the number of horns a god has on his crown, and in this case there is only one, so this gate figure is a minor protective deity. In the southwestern gateway there are two lion figures carved in protome, that is to say with their front parts emerging from the stone, but the rest of the animal not carved in the round. This tradition of having lions guarding gateways, while not original with the Hittites, is certainly one that had a long life in their artistic tradition.

The most impressive construction at the site was undertaken between these two gates, where

267

H I T T I T E D O M I N AT I O N A N D T H E L AT E B R O N Z E A G E

images would have stood on platforms at the back of these rooms. However, there was no direct access to the cult statues from the large courtyard where texts indicate many of the religious rituals were performed. A row of small rooms intervened and, at best, windows might have provided a limited view.

Besides the temple building itself, there are two other major components of the Great Temple complex. One is a series of magazines surrounding the temple building on all sides. These have the form of long, narrow rooms which must once have been filled with offerings and supplies essential to the cult. In some of these, on the east side of the temple, an archive comparable to, and indeed partially duplicating those found on Büyükkale was discovered. On the opposite side of the temple, some of the most massive storage jars known from the ancient world may be seen today, buried up to their shoulders and having a capacity of 2000 liters.29 South of the temple and across a paved street from its surrounding storage complex, there was another large building, which appears to have been devoted to the administrative functions of the temple. When all of these structures are viewed as a whole, one cannot fail to be impressed by the extensive economic and administrative apparatus that supported the worship of the Empire’s chief deities, irrespective of all the governmental activity taking place on the citadel of Büyükkale.

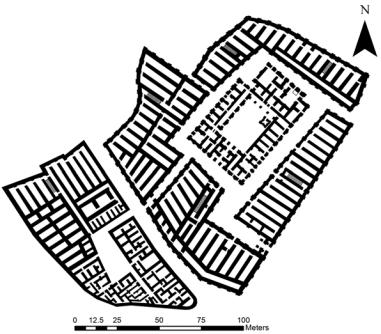

The other temples at Bog˘ azköy are located on higher ground, in the southern or upper city (Figure 7.8). Until not long ago, only four of these were known, but in the 1980s Peter Neve began excavating in a “sacred quarter” and discovered 25 more. Some are within enclosures and other stand alone. None has associated auxiliary buildings like the Great Temple, but they do all have somewhat similar plans, including a rectangular courtyard. These Hittite temples do not appear to be related to any types found elsewhere in the Near East, nor do they descend from the temples that are seen at Kanesh in the Middle Bronze Age. If anything, they seem to be derived from traditions Anatolian courtyard house architecture.

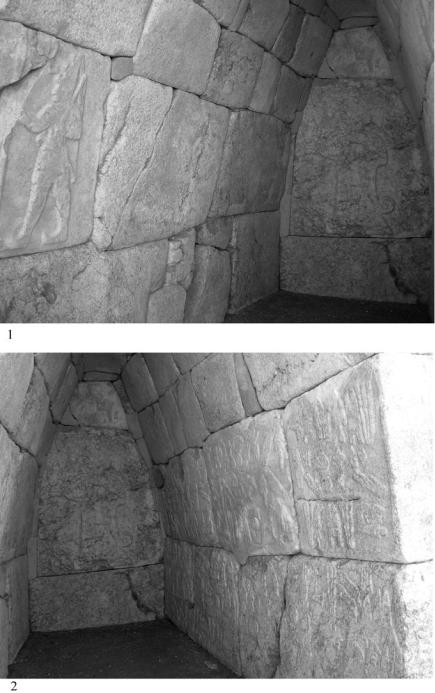

Within the Upper City there are several other focal points of cultic interest as well as remains of administrative activities. In two separate locations there were large pools, created deliberately by retaining water produced by springs. Stone walls reinforced with a waterproofing clay formed their embankments. Not far from the largest of these, 300 m south of Büyükkale, are two arched structures that form single-room blind chambers. It has been suggested that these represent the oldest arches of stone masonry in the ancient Near East.30 One of these, Chamber 2, had been partially dismantled in the Iron Age by people who were constructing a fortress in this area (the Südburg), but it has been possible for the excavators of Bog˘ azköy to reconstruct it almost completely since many of its stone blocks were covered with a hieroglyphic inscription- (Figure 7.9). These could be fitted back together like a jigsaw puzzle. The panel that forms the rear of the chamber is dominated by the figure of the Sun God in shallow relief, a large winged disc crowning his headdress. On the left entrance of the chamber, as one faces inward, is a somewhat smaller figure of Suppiluliuma II, holding a spear before him and bearing a bow on his shoulder. Curiously, he is wearing a crown with three horns on it, and thus a king is being represented here, uniquely, as a divinity. There can be no doubt about who he is, since his name is given by hieroglyphs carved in front of his face, albeit with the royal cartouche and titulary as

270

Figure 7.8 Temples in the upper city at Bog˘ azköy, from Google Earth image