- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

F O R E I G N M E R C H A N T S A N D N AT I V E S TAT E S

palace from which the Hittite realm was governed.33 These were the documents of the karum Hattusˇ, and that city name, which is regularly written Hattusˇa in the following period, gives its name to the land of Hatti. Approximately 75 more tablets come from the terrace of the mound at Alis¸ar, which was probably named Amkuwa in this period.34

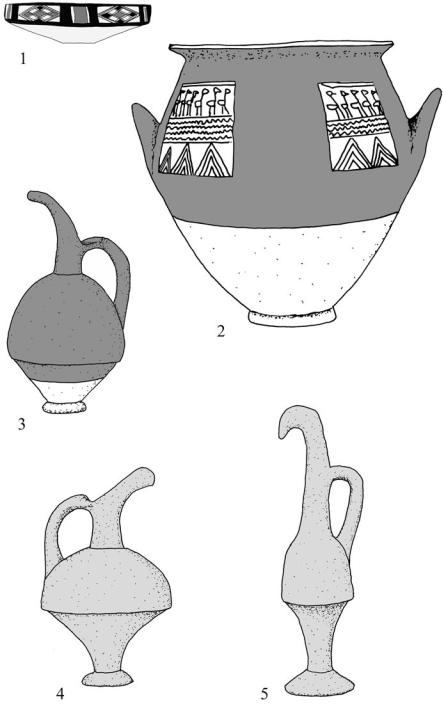

CENTRAL ANATOLIAN MATERIAL CULTURE OF THE MIDDLE BRONZE AGE

The emergence of this prosperous and cosmopolitan society coincided with the introduction of new ceramic traditions. Some of these were relatively short lived. A rather elaborate handmade pottery, known as “Cappadocian ware” (Figure 6.10: 1), is most often seen in open bowls. First identified in Alis¸ar Level III, it continued the trajectory of the “Intermediate Ware” of the late Early Bronze Age, but painted in multiple colors. Its geometric designs of horizontal bands, triangles, zigzags, and lozenges in red, black, and white paint make it one of the most colorful styles ever to develop in ancient Turkey. This ware does not seem to have been particularly widespread, being much rarer at sites at the north, like Bog˘ azköy, than it is at Kültepe. It also died out in the course of the Middle Bronze Age.

Another type of decoration is more often found on larger wheelmade pitchers and open vessels (Figure 6.10: 2). They are partially or wholly covered with a red to reddish-brown slip that is burnished to a low shine. Reserved rectangular areas on the vessel shoulders and rims are decorated with dark brown geometric patterns of the same sorts that are found in Cappadocian ware, but here without the color.

Perhaps more significant is the introduction of wheelmade wares with red or brown slips that are often polished. Some of the forms of the latter are quite distinctive. They include pitchers with long beaked spouts and containers on high pedestals (Figures 6.10: 3 and 6.10: 4). Vessels with attached animal figures gracing their handles or rims are quite common. This burnished ware is informally and not entirely correctly dubbed “Hittite ware” because it continues to be used, albeit evolving gradually until the end of the Bronze Age. In the period of the merchant colonies, it became a kind of standard throughout the plateau, yet there was still some local variation. Kutlu Emre found that beak-spouted pitchers, two-handled drinking cups, and some other types tended to be squatter and thicker at Acemhöyük than at Kültepe, although the overall shapes tended to be indistinguishable.35

The place where the cosmopolitanism of the era comes though most clearly is in the art revealed to us by seal impressions. Most of these are associated with the trading activities of the karum, appearing on the clay envelopes of letters and sealings associated with storage, such as the dockets found at Acemhöyük. It is not surprising, therefore, that these should include a mixture of both foreign and local elements.

External influence is apparent in the very shape of many of the seals. This period is virtually the only one in which the cylinder seal, so characteristic of Mesopotamia, is in widespread use. There was a long tradition of sealing in Anatolia, but it favored the use of stamp seals rather

240

F O R E I G N M E R C H A N T S A N D N AT I V E S TAT E S

than the friezes of design that come from the rolling of a cylinder. Cylinder seals were the norm in Assyria, as well as Syria, so the mere fact that they came into vogue in the trading colony period speaks for southern influence. Stamp seals, however, do not completely disappear, and one can see the waxing and waning of their importance throughout the period as a kind of index of the intensity of foreign participation in the Anatolian trade.

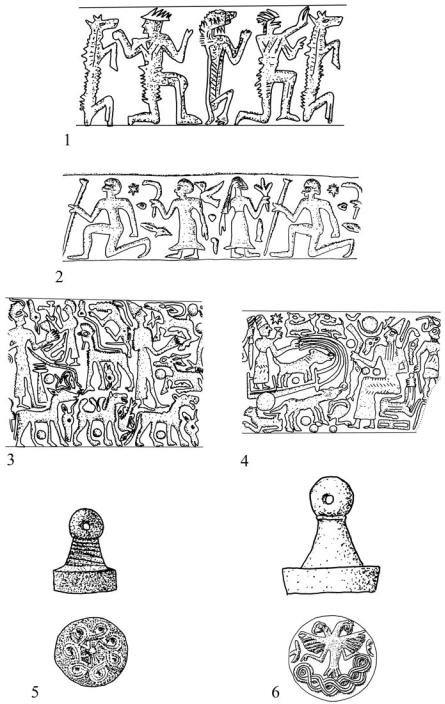

Nimet Özgüç, who has made several pioneering studies of the seals and seal impressions of Kültepe defines four major stylistic groups, three of which can be classed as outright imports: Old Babylonian (Figure 6.2), Old Assyrian (Figure 6.11: 1), and Old Syrian (Figure 6.11: 2). The fourth, and perhaps most interesting, is the termed the Anatolian Group (Figures 6.11: 3 and 6.11: 4). We cannot assume, however, that the style of the seal denoted the place of origin of the seal owner. Seals were valuable items, staying in use for a long time, and sometimes recut for new holders. Seals dating to southern Mesopotamia’s Third Dynasty of Ur (ca. 2100–2000 BC) were used at Kültepe, although their manufacture predates the context in which they were found by centuries. It is also clear from the texts on which they appear that both natives and Assyrians made use of seals in the Anatolian Group.

Old Babylonian seals were, of course, contemporary with the trading colonies and embraced a wide number of themes. One of the most common is the “presentation scene,” in which an individual is led into the presence of a seated deity by an interceding divinity. This basic motif is adopted and transformed in many of the scenes on the Anatolian Group seals. Manufacturing points for the widespread Old Babylonian seals would include not just southern Mesopotamia, but also Mari, which the Acemhöyük finds demonstrate was in contact with Anatolia. The Old Assyrian type is much more limited geographically and temporally, and is most easily distinguished by its processions of repeating figures and crude renderings of the garments of figures using parallel diagonal lines. There are at least two groups of the Syrian styles, an earlier one with groups of smaller figures and a later one with much larger, well-modeled figures.

The scenes of the Anatolian Group are most noteworthy for their clutter. Familiar Mesopotamian scenes are here, but they are transformed by the sealcutters’ abhorrence of a vacuum.

Spaces between larger figures are filled with animals, or parts of animals turned every which way. The gods in the presentation scenes sometimes wear the tall pointed horned crown that is much better known from Anatolia in the late Hittite Empire. In fact, many of the Anatolian deities who figure prominently in the cultic practices and mythology of later centuries, such as the Storm God and the Sun Goddess, probably find their first representation here, although we can say little of them in this period without extrapolation from the later texts.

Stamp seals never went out of use, and they appear to increase in popularity during the Karum Ib period (Figures 6.11: 5 and 6.11: 6). Generally, they have a flat stamping surface of a round or rectangular shape, and are held by a knob through which there was a hole to suspend them on a string. These tend to make smaller impressions than cylinder seals, and their themes are therefore more limited. The earliest stamp seals often have nothing more on them than hatch marks. In later periods the designs include familiar Anatolian themes, such as double-headed eagles.

242