- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

M E TA L S M I T H S A N D M I G R A N T S

tin—fuelled a shift in social structures in which items of precious metals acted as indicators of status and power.

Regional survey

Southeast Anatolia

After the collapse of the Uruk colonial network, interregional exchange patterns continued within substantially different organizational structures. The centralization of authority and its various manifestations virtually disappeared, and did not re-emerge until about 2600–2500 BC, when large urban centers and their polities began to dominate the landscape in response to a resurgence of Mesopotamian influences. Sandwiched between these two periods, the Early Bronze Age I–II developed a sociopolitical system that was essentially rural, attested by the small towns and villages scattered across the Anatolian foothills and plains.

In the Turkish Lower Euphrates Valley, our picture is determined largely by field surveys in those riverine areas that have now been flooded by the Atatürk, Birecik, and Carchemish dams.82 Our understanding of settlements in the plains, however, is poor, with the recently published results of the survey of the Harran Plain providing reasonable data.83 Stratified sequences, too, are relatively few and architectural exposures are restricted, a situation exacerbated by the drowning of a number of key centers, most notably Samsat. Even so, we can point to a number of changes in the early centuries of the third millennium.

In the first place, we can note a marked reduction in the size of sites. Kurban Höyük, for instance, a bustling village of four hectares in the Late Chalcolithic (Period VI) contracted to one hectare in the subsequent period. This pattern of a decrease in site size from the late fourth to the early third millennium BC is also reflected in the surrounding region where a number of settlements of similar dimensions are situated.84 A comparable shift in settlement pattern occurred at Hassek Höyük. There, walled enclosure gave way to groups of small houses (Figure 5.4: 2). Survey results, on the other hand, show that the number of sites actually increased in the postUruk period. These two features—a reduction in the size of settlements and an increase in their number—suggest a demographic shift to the countryside. Whereas this change from townsfolk to villagers may have accounted for a good portion of the population, others may well have adopted a more nomadic existence, making their presence in the archaeological record less visible.85

At first glance, the regional system linking these hamlets appears largely nonhierarchical. Yet some maintain that the three-tiered settlement structure of the preceding centuries basically continued in albeit substantially modified form, with fewer large sites.86 Samsat and Carchemish were now the dominant sites along the Turkish Lower Euphrates and therefore probably became nodes for communication. A landscape dotted with many small sites would not have encouraged a closed system rather than regional integration, with production based largely around

178

M E TA L S M I T H S A N D M I G R A N T S

households. This change in settlement pattern may also reflect the shifting routes of trade that appear to have favored the Khabur and Tigris basin rather than the Euphrates in the early third millennium BC.87 Even so, while trade may have been scaled down along the Turkish Euphrates corridor, it certainly did not collapse.88 Grave goods in the form of metal artefacts and jewellery items from the Birecik and Hassek Höyük cemeteries leave no doubt that many families were still prosperous.

Two broad culture provinces can be discerned, even though nomenclature and chronology remain matters of considerable debate:89 A western zone, stretching from the Amuq Plain (Hatay) to the Euphrates River, which is distinguished by a ceramic horizon that includes Late

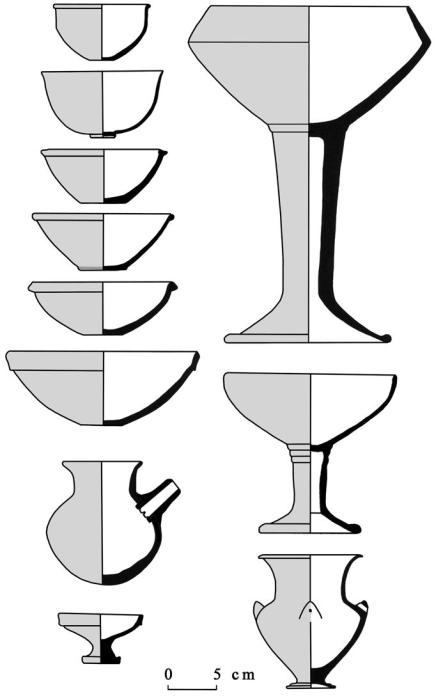

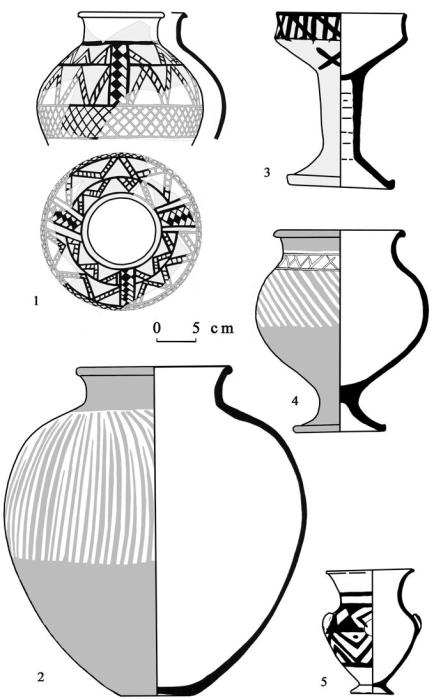

Reserved Slip, Plain Simple Ware, and Red-Black Burnished Ware;90 and an eastern region-based zone in the Tigris drainage system where the Ninevite 5 assemblage is common. The main trend at the beginning of the third millennium is the disappearance of chaff-tempered wares and their replacement with grit-tempered Plain Simple Ware, which was already present in smaller quantities in the Late Chalcolithic period.91 Core types like hemispherical bowls with thickened or folded rims are now associated with a range of new shapes: Cups with a sinuous profile (the socalled cyma recta curve) and delicate ring base, and bowls with a pedestal or stemmed base (Figures 5.16 and 5.17). Late Reserved Slip Ware, a development of the earlier Late Chalcolithic version, and its eye-catching ornamentation, is not as common, but present in all sequences. The third fabric group is cooking pot ware, represented by handmade simple bowls and round-bodied pots with a hole mouth.

Radical shifts in social and political structures and innovations in metal technology characterize the Early Bronze Age III ca. 2500–2000 BC. Large cities and centers developed at Tirtis¸, Samsat, Lidar, and Kazane south of the Taurus, as southeastern Anatolia became absorbed into the far-flung territorial network of the Akkadian Empire. As with the Uruk phenomenon, what is not altogether clear is the degree of influence external dynamics had in the emergence of urbanism in southeastern Turkey. Tirtis¸ Höyük, the capital of a small city-state that lasted about 300 years (2500–2200 BC), is a crucial site. The growth of the city has been elucidated through a skillful combination of detailed geophysical prospection and select excavation.92 Covering an area of 43 ha, the site comprises a high mound, where presumably the ruler lived amidst the central administrative quarters, and suburbs that stretched across the lower and outer town sectors. A massive fortification wall surrounded the entire city; at some distance was the cemetery. The overall plan is suggestive of a highly organized, central authority with a clear predetermined idea of design. Large public buildings, constructed both on the high mound and in the lower areas, were the focal points of a comfortable and bustling city. Substantial terraces point to the levelling of areas before the construction of the domestic quarters, which were provided with wide streets, well-built houses of standard plan that were fitted with sewerage facilities.

That the houses closest to the high mound were larger, may point to the status of its occupants. Yet despite the urban character of Titris¸, the frequent occurrence of sickle blades in houses indicates that its residents were still closely tied to the land and the agricultural cycle. Other specialized activities include textile manufacture, wine production, and the knapping of

179