- •Preface

- •Acknowledgments

- •1 Introduction

- •The land and its water

- •Climate and vegetation

- •Lower Palaeolithic (ca. 1,000,000–250,000 BC)

- •Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 250,000–45,000 BC)

- •Upper Palaeolithic and Epipalaeolithic (ca. 45,000–9600 BC)

- •Rock art and ritual

- •The Neolithic: A synergy of plants, animals, and people

- •New perspectives on the Neolithic from Turkey

- •Beginnings of sedentary life

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •North of the Taurus Mountains

- •Ritual, art, and temples

- •Southeastern Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Contact and exchange: The obsidian trade

- •Stoneworking technologies and crafts

- •Concluding remarks

- •Pottery Neolithic (ca. 7000–6000 BC)

- •Houses and ritual

- •Southeastern Anatolia and Cilicia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia and the Aegean coast

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Seeing red

- •Invention of pottery

- •Cilicia and the southeast

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Other crafts and technology

- •Economy

- •Concluding remarks on the Ceramic Neolithic

- •Spread of farming into Europe

- •Early and Middle Chalcolithic (ca. 6000–4000 BC)

- •Regional variations

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •The central plateau

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwest Anatolia

- •Metallurgy

- •Late Chalcolithic (ca. 4000–3100 BC)

- •Euphrates area and southeastern Anatolia

- •Late Chalcolithic 1 and 2 (LC 1–2): 4300–3650 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 3 (LC 3): 3650–3450 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 4 (LC 4): 3450–3250 BC

- •Late Chalcolithic 5 (LC 5): 3250–3000/2950 BC

- •Eastern Highlands

- •Western Anatolia

- •Northwestern Anatolia and the Pontic Zone

- •Central Anatolia

- •Early Bronze Age (ca. 3100–2000 BC)

- •Cities, centers, and villages

- •Regional survey

- •Southeast Anatolia

- •East-central Anatolia (Turkish Upper Euphrates)

- •Eastern Anatolia

- •Western Anatolia

- •Central Anatolia

- •Cilicia

- •Metallurgy and its impact

- •Wool, milk, traction, and mobility: Secondary products revolution

- •Burial customs

- •The Karum Kanesh and the Assyrian trading network

- •Middle Bronze Age city-states of the Anatolian plateau

- •Central Anatolian material culture of the Middle Bronze Age

- •Indo-Europeans in Anatolia and the origins of the Hittites

- •Middle Bronze Age Anatolia beyond the horizons of literacy

- •The end of the trading colony period

- •The rediscovery of the Hittites

- •Historical outline

- •The imperial capital

- •Hittite sites in the empire’s heartland

- •Hittite architectural sculpture and rock reliefs

- •Hittite glyptic and minor arts

- •The concept of an Iron Age

- •Assyria and the history of the Neo-Hittite principalities

- •Key Neo-Hittite sites

- •Carchemish

- •Zincirli

- •Karatepe

- •Land of Tabal

- •Early Urartu, Nairi, and Biainili

- •Historical developments in imperial Biainili, the Kingdom of Van

- •Fortresses, settlements, and architectural practices

- •Smaller artefacts and decorative arts

- •Bronzes

- •Stone reliefs

- •Seals and seal impressions

- •Urartian religion and cultic activities

- •Demise

- •The Trojan War as prelude

- •The Aegean coast

- •The Phrygians

- •The Lydians

- •The Achaemenid conquest and its antecedents

- •Bibliography

- •Index

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

chevrons and hatched patterns fired to distinct shades or buff and orange. Similarly striking pottery has been found at Çatalhöyük West.

Influences from southeastern European were now penetrating further into Anatolia than before. In the central plateau and especially at Alis¸ar Höyük black burnished carinated vessels with decorated fluted patterns recall the Vincˇa horizon.133 Dishes with thickened rims ornamented in this fashion have been compared to those found at Anza IVA, Vincˇa-Belo Brdo, Vesselinovo in the Balkans, and with examples at Can Hasan 2b and Yarımburgaz 0. Influences associated with post-Vincˇa horizons (i.e., Maritsa, Pre-Cucteni and Gumelnitsa) are also appar-

˙

ent at a number of central Anatolian sites such as Büyük Güllücek, Dundartepe, Ikiztepe, Yazır Höyük, Bog˘ azköy-Yarıkkaya, Gelveri-Güzelyurt, and Bucak Hüyücek (Figure 4.23).134 Whether evidence comes through excavations or field surveys, the chronology of central Anatolia remains a major obstacle.

Western Anatolia

Within this broad region three Chalcolithic clusters can be identified: The southwestern, the Aegean coast, and the area in between. The Early Chalcolithic settlement at Hacılar (V–III) has left traces. Those inhabitants who continued to live at the site appear to have reorganized its plan—the area occupied by the previous Late Neolithic settlement (Hacılar VI) was turned into courtyards.135 Hacılar II provides good evidence of a southwestern Anatolian village from the first half of the sixth millennium BC. The settlement assigned to Level IIA was oblong in shape and enclosed by a thick mud brick wall equipped with small buttresses.136 Several activity areas could be discerned around a main central courtyard—a residential quarter in the west, potters’ workshop within the courtyard, a cluster of cooking areas, and two possible shrines (Figure 4.24). An average house had a doorway, facing the courtyard, which led directly into an anteroom that was attached to the main room. Most houses were fitted with a square or rectangular oven set into the floor of the main room, storage bins, and benches; some houses also supported an upper story. The number of querns and mortars found lying on the floor of the central courtyard associated with lumps of red and yellow ochre, painting utensils, clay modeling tools, and stacks of unused pottery are suggestive of a craft area reasonably identified as a potters’ workshop. Another specialist area is located in the northwest corner where large amounts of grain strewn across the floor, equipped with storage bins and two large, oval ovens, point to a granary. The architectural complex at the other end of the settlement, the eastern side, was partitioned with brushwood barriers, partly roofed, and fitted with the usual features of a domestic area. A stone-lined well was also found nearby.

Whether the large building to the northeast corner is a shrine, as Mellaart proposes, is a moot point. Open plan in layout, the building has thin walls like those of the potters’ quarters, suggesting that it did not have an upper story. His judgement is largely based on size of the building, fragments of painted plaster associated with a niche, remains of standing stones, a

130

Figure 4.24 Plan of Hacılar II A (adapted from Mellaart 1970)

A N AT O L I A T R A N S F O R M E D

mound, although little evidence survives apart from a few postholes. Rooms were mostly square and internally buttressed. They were generally fitted with benches and hearths that were raised on a platform, whereas domed ovens were found in the courtyards. Floors were coated with mud plaster, as were the walls, and covered with woven mats. But these basement rooms appear to have been empty apart from the material that collapsed from the upper story. Mellaart suggested that the plan of this settlement—with the back walls of the houses forming an unbroken façade—is defensive. But there is no evidence to support this idea. Roughly contemporary with Hacılar I is Kuruçay Level 7, a settlement of the clustered houses.137

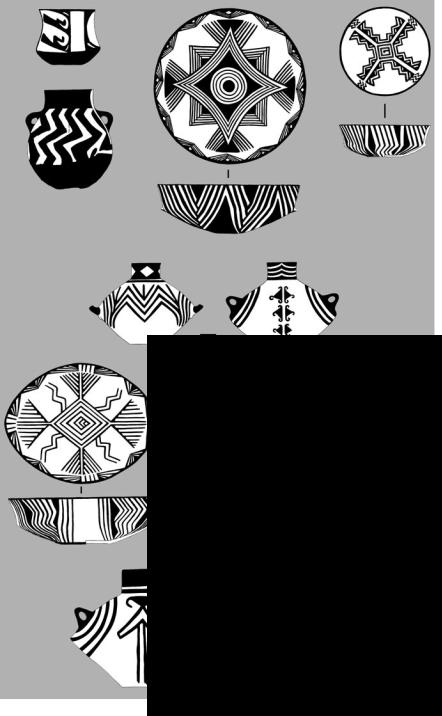

Striking red-on-cream painted pottery is generally seen as the hallmark of the Early Chalcolithic period in southwestern Anatolia (Figure 4.26), which nonetheless develops from the end of Late Neolithic. Moreover, the Hacılar painted style of linear decoration appears to be quite localized, extending as far south as Karain. Painted patterns on the Hacılar repertoire vary—one portrayed stylized versions of Late Neolithic applied motifs, another depicted textile designs, using positive and negative techniques. The range of forms increased—there are now oval cups, and, in Level II, the appearance of anthropomorphic vessels and spouted jars. Monochrome ceramics continued to be manufactured, but were fewer in number than in the previous phase. Statuettes also showed changes. They are larger, more standarized, often painted to display garments, and devoid of animals and children. Potters continued to experiment with new forms—oval and subrectangular shapes, square cups, and ovoid butter churns. But, on the whole, vessels became more open, and the most popular shapes were carinated bowls and jars with wide necks. Among the most notable vessels are the painted anthropomorphic seated figure with prominent eyebrows and noses, and eyes that are either painted defined by chips of inlaid obsidian. Corpulent statuettes were still made, but now alongside a new type—stylized figurines with narrow waists. In the Elmalı Plain only a few sherds have been found of the Hacılar painted variety. Most of the Early Chalcolithic pottery from Elmalı simply shows a continuation of the Late Neolithic tradition—coil-built monochrome vessels of rounded forms.

While the period between the end of the Hacılar culture and the beginning of the Beycesultan

Late Chalcolithic has been described as “the greatest possible break imaginable,”138 traditional chronology has also assumed that there was little if any gap. We now realize that a hiatus of considerable length of time separates the two periods into which we can now place the Elmalı Plain (Kızılbel and Lower Bag˘ bas¸ı), Kuruçay, Ilıpınar, basal Demircihöyük, and Orman Fidanlıg˘ ı.139 The Elmalı sites are also significant because of the evidence they provide for relations with the east Aegean. Ceramic features such as strap handles decorated with knobs, pans with high walls and pierced rims, and the occasional incised design have parallels in the earliest deposits at Emporio on Chios (Levels X–IX), at Tigani on Samos, and the cave sites on Kalymnos.140 Geographically, this communication between the Elmalı Plain and the eastern

Aegean could have been effected using a maritime route—along the western and southern coastline and then up to the plain—or an overland one—following the Büyük Menderes to the Burdur area and then to Elmalı.

134