- •Preface

- •Contents

- •Contributors

- •1 The Nature of Culture: Research Goals and New Directions

- •References

- •Abstract

- •The Primitive Tasmanian Image

- •Assessment of a Minimum of Cultural Capacities from a Set of Cultural Performances

- •Conclusions: Lessons from Tasmania

- •References

- •3 Culture as a Form of Nature

- •Abstract

- •The Status Quo of Nature

- •Culture as a Variation of Nature

- •The Dense Context of Nature

- •The Problem of Conscious Inner Space

- •Consciousness as a Social Organ

- •The Meaning of Signs

- •The Role of Written Language

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Evidence for Animal Social Learning, Traditions and Culture

- •Social Information Transfer

- •Traditions

- •Multiple-Tradition Cultures

- •Cumulative Culture

- •Multiple-Tradition Cultures

- •Cultural Content: Percussive Technology

- •Social Learning Processes

- •Concluding Remarks

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Typology of Limestone Artifacts

- •Cores and Core-Tools

- •Flakes and Flake-Tools

- •Technology of Limestone Artifacts

- •Cores and Core-Tools

- •Flakes and Flake-Tools

- •Cognitive Abilities

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Technological Transformations

- •Cultural Transformations

- •Closing Remarks on the Nature of Homo sapiens Culture

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •7 Neanderthal Utilitarian Equipment and Group Identity: The Social Context of Bifacial Tool Manufacture and Use

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Style in the Archaeological Discourse

- •The Archaeological Evidence

- •Discussion and Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Human Life History

- •Cognitive Development in Childhood

- •The Evolutionary Importance of Play

- •What Is Play?

- •Costs and Benefits of Play

- •Why Stop Playing?

- •Fantasy Play

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •What Is Culture?

- •Original Definitions

- •Learned Behavior

- •Culture and Material Culture

- •Models of Culture in Hominin Evolution

- •Conclusion

- •Acknowledgments

- •References

- •11 The Island Test for Cumulative Culture in the Paleolithic

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •The Island Test for Cumulative Culture

- •Geographic Variation

- •Temporal Variation

- •The Reappearance of Old Forms

- •Conclusions

- •Acknowledgements

- •References

- •12 Mountaineering or Ratcheting? Stone Age Hunting Weapons as Proxy for the Evolution of Human Technological, Behavioral and Cognitive Flexibility

- •Abstract

- •Introduction

- •Single-Component Spears

- •Stone-Tipped Spears

- •Bow-and-Arrow Technology

- •But, Is It Ratcheting?

- •Or Is It Mountaineering?

- •Acknowledgments

- •Index

Chapter 12

Mountaineering or Ratcheting? Stone Age Hunting Weapons as Proxy for the Evolution of Human Technological, Behavioral and Cognitive Flexibility

Marlize Lombard

Abstract Cultural, behavioral and cognitive evolution is often seen as cumulative and sometimes referred to in terms of a ratchet or the ratchet effect. In this contribution, I assess the value of the ratchet analogy as blanket explanation for the above aspects of human evolution. I use Stone Age weapon technologies as proxy for the evolution of human technological, behavioral and cognitive flexibility, and by doing so show that the ratchet analogy falls short of explaining human variability and complexity as reflected in the Stone Age archaeological record. Considering human cultural, behavioral and cognitive evolution from a theoretically constructed rugged landscape point of view, I suggest that mountaineering may be a more suitable analogy for the accumulation of human culture. In this scenario, culture and technology anchor societies within their respective evolutionary trajectories and fitness landscapes, and it more accurately reflects humans as ‘masters of flexibility’.

Keywords Projectiletechnology Bow-and-arrow Spear Spearthrower-and-dart Cumulative culture Cognition Fitness landscapes

Introduction

Flexibility is the ability of an organism to change and adapt to suit new conditions or situations. This ability applies to long-term adaptability and change, as well as to

M. Lombard (&)

Department of Anthropology and Development Studies, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa

e-mail: mlombard@uj.ac.za

and

Wallenberg Research Centre, Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Stellenbosch University, Marais Street, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa

instantaneous decision-making processes. All living things are flexible in a biologically relevant way, but, because we have certain features in our brains that make us more flexible than any other organism, humans are considered ‘masters of flexibility’ (Barrett 2009:107). Our extraordinary flexible nature is expressed, for example, in the way we think, in our social behaviors, and in our production and use of technology. As a species, we have become almost unlimited in how we adapt and change to suit new conditions and situations. We are versatile and creative in how we tackle immediate challenges, and ambitious in ensuring our long-term survival on earth – and possibly beyond.

It is our highly developed flexibility that also causes us to deem ourselves ‘intelligent’, as intelligence is seen as the ability to learn, innovate and respond flexibly to new or complex situations (Byrne 1995; van Schaik and Burkart 2011). These abilities are anchored in genetic predispositions towards faster reaction times, greater working memory, inhibitory control and greater response to novelty (Geary 2005; van Schaik and Burkart 2011). From a dynamic systems perspective, intelligence is the adaptive flexibility that integrates the stability of past experience with the idiosyncrasies of the moment (Colunga and Smith 2007:170). These notions all seem to indicate that humans are hardwired to use past knowledge and experience, together with novel ideas and applications, to negotiate any given situation as quickly and effectively as possible. Today, as in the past, much of human flexibility is reflected in the variability of our material culture or technologies, whether these are our transport systems, agriculture, water supply systems, information technology or space exploration. In many ways we have become dependent on technologies for our survival. But, when did we become such masters of flexibility?

To explore this question we need to journey back in time. Early human material culture is represented in the archaeological records of the last 3 Myr; first in Africa, and then elsewhere in the Old World. These archaeological records inform on technology, or the way that early humans applied knowledge in practical ways. The bulk of past human

© Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2016 |

135 |

Miriam N. Haidle, Nicholas J. Conard and Michael Bolus (eds.), The Nature of Culture:

Based on an Interdisciplinary Symposium ‘The Nature of Culture’, Tübingen, Germany,

Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology, DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-7426-0_12

136 |

M. Lombard |

technological endeavor is captured in stone artifacts, and it is from these objects that archaeologists and other researchers interested in the evolution of human culture, behavior and cognition, are challenged to extract as much information as possible.

For the Nature of Culture symposium, I was asked to follow the development of human flexibility through deep time. My research explorations mostly focus on the evolution of hunting technologies as a possible line of evidence for tracing levels of technological complexity and flexibility through time and space (e.g., Lombard 2005, 2007, 2011). Thus, in this paper I will use examples of Stone Age hunting technologies as proxy for the evolution of human flexibility in general. The hunting technologies used as examples are mostly based on my own research experience. They include simple wooden spears as representing single-unit (unhafted) technologies, stone-tipped spears as representing composite technologies, and bow-and-arrow sets as representing complementary tool sets or symbiotic technologies (see Lombard and Haidle 2012).

Focus on these technologies does not exclude other weapon systems from the main argument; they are seen as generally representative of the technological expressions mentioned above. For example, the use of spearthrowers is sometimes considered intermediate to hand-delivered weaponry and bows and arrows, but there is no reason to view bow-and-arrow technology as necessarily originating from spearthrower-and- dart technology, or vice versa (e.g., Shea 2006). Spearthrower technology also represents complementary tool sets akin to bow-and-arrow technology, so that inferred levels of complexity, variability and flexibility regarding these two mechanically-projected weapon systems is presumed similar (Lombard and Haidle 2012). So far there is little or no indication that the former was ever used in sub-Saharan Africa and more direct evidence exists for the production and use of the latter in southern Africa associated with the Middle Stone Age; a focus area and period for exploring human behavioral and cognitive evolution (e.g., Wadley et al. 2009, 2011; Wadley 2010; Henshilwood and Dubreuil 2011).

Archaeological evidence reveals that the use of weapon systems came and went over the course of time, with wide variation in the degree to which regional human populations used them (e.g., Shea 2006; Lombard 2011; Lombard and Parsons 2011). Based on the Stone Age archaeological record I will critique the use of a ratchet or the ratchet effect (e.g., Riegler 2001; Tennie et al. 2009), as an apt, broad-spectrum explanation for human cultural and behavioral evolution. As an alternative analogy for cumulative culture, I reintroduce the idea of rugged and complex fitness landscapes (Wright 1932; Kuhn 2006), negotiated by human societies in a flexible way (Lombard and Parsons 2011; Parsons and Lombard 2011), more similar to mountaineering than to ratcheting.

An Abbreviated Account

of the Evolution of Human Hunting

Technologies

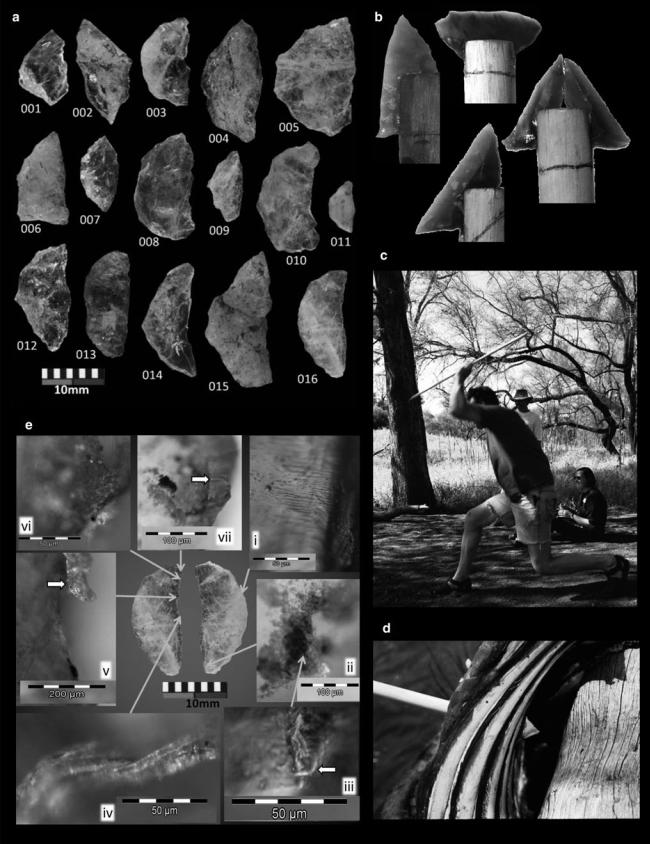

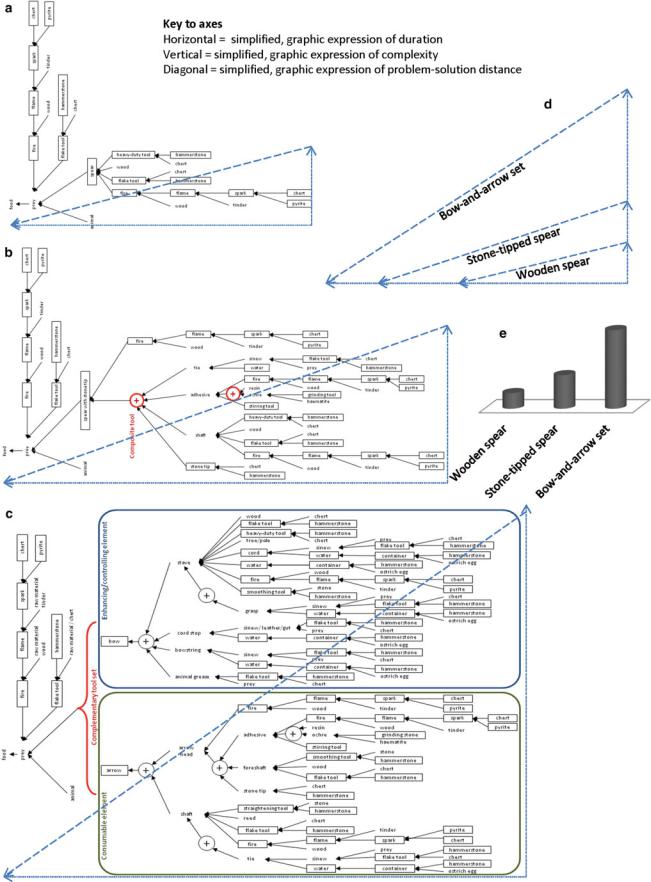

It has recently been established that humans are not the only beings who hunt with weapons (e.g., Preutz and Bertolani 2007), but together with our immediate Homo ancestors and ‘cousins’, such as Homo neanderthalensis, we are the only ones who modified (or still modify) our weapons with other tools before use, or who tipped them with stone. The latter behavior sometimes results in the preservation of information about our early hunting technologies over long periods of time. Stone tool analysis (e.g., Wadley and Mohapi 2008) (Fig. 12.1a), in combination with experimental archaeology (e.g., Lombard et al. 2004; Wadley 2005; Lombard and Pargeter 2008; Bradfield and Lombard 2011) (Fig. 12.1b, c, d), and use-trace studies (e.g., Lombard 2011) (Fig. 12.1e), occasionally provide detailed insight into past hunting technologies and their associated behaviors. Using multiple strands of evidence to reconstruct and hypothesize about Stone Age weaponry helps to build increasingly comprehensive thought-and-action or operational sequences, providing insight into the more abstract notions of cultural evolution and behavioral and cognitive flexibility (e.g., Haidle 2009, 2010; Wadley et al. 2009; Wadley 2010; Lombard and Haidle 2012; Williams et al. 2014).

Single-Component Spears

At *300 ka Homo heidelbergensis in Europe used sharpened, wooden spears as hunting weapons, such as those found at Schöningen (Thieme 1997, 1999). At first glance, these spears seem to be simple, single-component weapons. Yet, when we explore what they were made of, and how they were produced, a more complex picture emerges. Haidle’s (2009, 2010) effective chain of production and use shows that making wooden spears required the collection and preparation of several other materials before production could begin (Fig. 12.2a). If we accept that sharp-edged stone tools were used to remove bark, smooth and sharpen the wood, and that heat was used to shape, sharpen or temper the spears, then it follows that various plant materials were needed to produce the spears, and to start and maintain fires. Furthermore, a range of rocks were collected, either to use as tools or to light fires (Haidle 2009, 2010; Lombard and Haidle 2012). The operational sequence is extended in duration and complexity, compared to using objects that have not been altered with other objects or agents (e.g., heat), and thus the problem-solution distance is also extended (Haidle 2010) (Figs. 12.2a and 12.3a). Within each of the

12 Stone Age Hunting Weapons |

137 |

Fig. 12.1 Multiple ways of studying ancient hunting technologies include: a Stone tool analyses such as that conducted on the 60–64 ka backed quartz tools from Sibudu Cave South Africa by Wadley and Mohapi (2008). b–d Reconstructing and using stone-tipped weapons in

replication experiments (b from Lombard and Pargeter 2008; c and d from Lombard et al. 2004). e Conducting use-trace analyses on experimental and suitable archaeological samples (from Lombard 2011)

138 |

M. Lombard |