- •Chapter 7

- •7.0 Introduction

- •202 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •204 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •206 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •208 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •210 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •212 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •214 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •216 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •218 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •220 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •7.5 Montague grammar

- •224 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •226 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •7.6 Possible worlds

- •228 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •230 The formalization of sentence-meaning

- •8.0 Introduction

- •8.1 Utterances

- •8.2 Locutionaryacts

- •9.0 Introduction

- •9.1 Text-sentences

- •9.6 What is context?

214 The formalization of sentence-meaning

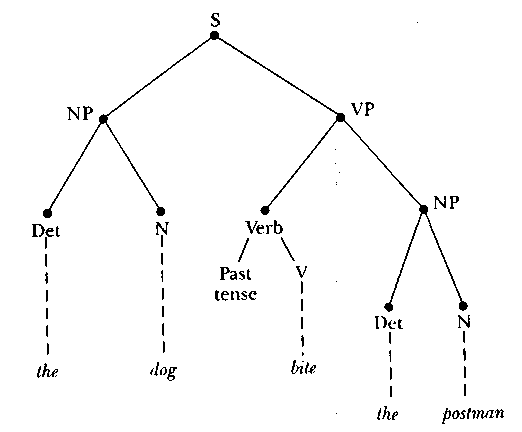

For example, corresponding active and passive sentences (which differ in thematic structure), such as

'The dog bit the postman' and

'The postman was bitten by the dog',

Figure

7.2 Simplified representation of the deep structure of 'The dog bit

the postman'

and of 'The postman was bitten by the dog'.

7.4 Projection-rules and selection-restrictions 215

6, examples (l)-(4) and (5)-(6). For syntactic reasons that do not concern us here, sets of sentences such as 'I have not read this book', 'This book I have not read', etc. are given the same deep structure in the standard theory, whereas corresponding active and passive sentences are not. But this fact is irrelevant in the context of the present account. So too is the fact that much of the discussion by linguists of the relation between syntax and semantics has been confused, until recently, by the failure to distinguish propositional content from other kinds of sentence-meaning. The point that is of concern to us is that some sentences will have the same deep structure, though they differ quite strikingly in surface structure, and that all such sentences must be shown to have the same propositional content. This effect is achieved, simply and elegantly, by organizing the grammar in such a way that the rules of the semantic component operate solely upon deep structures.

7.4 PROJECTION-RULES AND SELECTION-RESTRICTIONS

We now come to the notions of projection-rules and selection-restrictions as these were formalized by Katz and Fodor (1963) within the framework of Chomskyan transformational-generative grammar.

In the Katz-Fodor theory the rules of the semantic component are usually called projection-rules. In the present context, they may be identified with what are more generally referred to nowadays as semantic rules. They serve two purposes: (i) they distinguish meaningful from meaningless sentences; and (ii) they assign to every meaningful sentence a formal specification of its meaning or meanings. I will deal with each of these two purposes separately.

We have already seen that the distinction between meaningful and meaningless sentences is not as clear-cut as it might appear at first sight (see 5.2). And I have pointed out that, in the past, generative grammarians have tended to take too restricted a view of the semantic well-formedness of sentences. In this section we are concerned with the formalization of semantic