jost_j_t_kay_a_c_thorisdottir_n_social_and_psychological_bas

.pdf

C H A P T E R 1 2

A Dual Process Motivational

Model of Ideological Attitudes

and System Justification

John Duckitt and Chris G. Sibley

Abstract

This chapter reviews recent theory and research on the dual process cognitivemotivational model of ideology and prejudice. Consistent with a dual process model perspective, the authors argue that Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) and Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) assess dual ideological attitude dimensions that are made salient for the individual by competitive and dangerous worldviews, respectively, which in turn result from the combination of socio-structural factors (resource scarcity, danger and threat) and individual differences in personality (primarily low agreeableness and low openness to experience). Finally, the authors extend the model by arguing that SDO and RWA elicit dual ideologies that stratify and position groups based on qualitatively different stereotype characteristics. A competitively driven motivation (indexed by SDO) should cause the individual to endorse legitimizing myths or ideologies that are explicitly tailored toward maintaining hierarchical relations between groups. A threatdriven security-cohesion motivation (indexed by RWA) should, in contrast, cause the individual to endorse legitimizing myths that emphasize the maintenance of ingroup norms and values. Recent experimental and longitudinal research supporting the model is described.

The issue of how sociopolitical attitudes, or ideological attitudes, are structured and organized is clearly one that is fundamental for understanding the social and psychological bases of these attitudes. Historically, social psychologists have favored a unidimensional approach, seeing ideological attitudes as organized along a single left (liberal) to right (conservative) dimension. During the past few decades, however, the weight of empirical evidence has shifted in favor of a two-dimensional approach. Increasingly research has shown that there seem to be two quite distinct dimensions of ideological attitudes that have very different social and psychological origins. These two dimensions may sometimes be strongly related, but often are not. They often have similar effects and outcomes, producing similar political affiliations

292

A Dual Process Motivational Model |

293 |

|

|

and stances on socio-political issues, but these are typically differentially caused or mediated.

THE CLASSICAL UNIDIMENSIONAL APPROACH

TO PSYCHOLOGY AND IDEOLOGY

The first major investigation of the psychological basis of ideology was that by Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswick, Levinson, and Sanford (1950), reported in their influential book, The Authoritarian Personality. The findings from their research indicated that people’s socio-political attitudes seemed to be highly correlated. Thus, they found that anti-Semitism, prejudice toward other outgroups and minorities, politically conservative attitudes, and excessive and uncritical patriotism all covaried strongly to form a unitary attitudinal syndrome. This provided what appeared to be powerful empirical support for the idea that ideological beliefs were organized along a single unidimensional continuum, with liberal or socialist attitudes at one pole and conservative and pro-fascist attitudes at the other.

A second major finding from their research suggested that clear individual differences existed between persons high and low in prejudice and ethnocentrism. Adorno and colleagues (1950) characterized this as an authoritarian personality dimension, and saw the high (authoritarian) end of that dimension comprising a tightly clustered set of nine interrelated traits, including traits such as conventionalism, authoritarian aggression, authoritarian submission, a preoccupation with power and toughness, destructiveness, and cynicism. They therefore argued that this dimension of personality caused people to adopt particular ideological attitudes, with persons low on this dimension tending to adopt liberal, left-wing ideological attitudes, and persons high on this dimension adopting conservative, ethnocentric, nationalistic, and profascist attitudes.

Several prominent alternative theories of the psychological bases of ideological beliefs followed Adorno and colleagues’ original theory. Instead of Adorno et al.’s (1950) complex set of underlying psychodynamics and inner conflicts, Allport (1954) saw the core underlying characteristic of the authoritarian personality as ego weakness, that is, fearfulness, psychological inadequacy, and personal insecurity. As a result, authoritarian personalities needed structure, order, and control in their personal life and social environments; feared unconventionality, novelty, and change; desired coercive, repressive social control; and supported tough, anti-democratic right-wing leaders and political parties. This emphasis on submissive, fearful “authoritarian” traits, rather than the dominant, power, and toughness traits, which Adorno and

294 |

PERSONALITY AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES |

|

|

colleagues (1950) had also included in the syndrome, was largely followed by later theorists such as Wilson (1973) and eventually also adopted by Altemeyer (1981).

OVERVIEW OF UNIDIMENSIONAL MODELS

Overall, early approaches to the study of ideological attitudes and their psychological basis showed a considerable degree of agreement. They shared two major assumptions: that ideological attitudes were unidimensionally structured along a single left–right or liberal–conservative dimension, and that a particular coherent cluster or dimension of personality traits or individual differences was a major causal determinant of the individuals’ location on this dimension. A major problem for this approach has been the refusal of measures of ideological attitudes to conform consistently to unidimensionality. This has been largely responsible for a retreat from these unidimensional approaches during the last few decades, during which new research has seriously undermined the idea that ideological attitudes might be unidimensionally structured and have common causes.

The second assumption of this approach that ideological attitudes are causally determined by a common set of causal factors, such as an authoritarian personality, has gained somewhat more support. This was shown by a recent meta-analysis of research by Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, and Sulloway (2003). Their analysis evaluated a number of likely correlates of rightversus left-wing political orientation and attitudes, which were operationalized as involving attitudes and actions expressing both resistance to change and justifying inequality. They found significant correlations with perceived social threat; death anxiety; dogmatism and intolerance of ambiguity; openness to experience; uncertainty tolerance; needs for order, structure, and closure; integrative complexity; fear of threat and loss; and a weak although significant correlation with low self-esteem.

SOCIAL DOMINANCE ORIENTATION AND RIGHT-WING AUTHORITARIANISM AS TWO DIMENSIONS OF IDEOLOGICAL ATTITUDES

During the past two decades, the idea that there might be two distinct dimensions of ideological social attitudes has gained increasing empirical support. First, Altemeyer (1981) developed the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale, which, unlike its failed predecessor, the F-scale, was clearly unidimensional and had a high level of internal consistency. Altemeyer limited the scope of his RWA scale to attitudinal expressions of just three of the original nine characteristics investigated by Adorno and colleagues (1950): conventional-

A Dual Process Motivational Model |

295 |

|

|

ism, authoritarian submission, and authoritarian aggression. Later, in the 1990s, Jim Sidanius and Felicia Pratto (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994) developed a second measure that seemed to pertain to a different cluster of Adorno and colleagues’ (1950) original nine authoritarian characteristics. This Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) scale taps a “general attitudinal orientation toward intergroup relations, reflecting whether one generally prefers such relations to be equal, versus hierarchical” (Pratto et al., 1994, p. 742).

Research has shown that both SDO and RWA powerfully predict a range of socio-political and intergroup behavioral and attitudinal phenomena such as right-wing political party support, anti-democratic sentiments, generalized prejudice, and ethnocentrism (Pratto, 1999; Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius, Pratto, & Bobo, 1994). Although this might have initially suggested that RWA and SDO were both measuring very similar or perhaps the same dimension of ideological attitudes, research has not supported this. The findings indicate that SDO and RWA scales measure different dimensions that are often independent of each other (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2001).

First, the item content of the two scales is clearly different. RWA items express beliefs in coercive social control, obedience and respect for existing authorities, and conforming to traditional moral and religious norms and values. SDO items, on the other hand, pertain to beliefs in social and economic inequality as opposed to equality, and the right of powerful groups to dominate weaker ones.

Second, research has indicated that RWA and SDO scales correlate differently with important other variables (Altemeyer, 1998; Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Fisher, 2003; Duckitt, Wagner, du Plessis, & Birum, 2002; McFarland, 1998; McFarland & Adelson, 1996). RWA is powerfully associated with religiosity and valuing order, structure, conformity, and tradition, whereas SDO is not. SDO, on the other hand, is strongly associated with valuing power, achievement, and hedonism and being male, whereas RWA is not. RWA is influenced by social threat and correlates with a view of the social world as dangerous and threatening, whereas SDO is powerfully correlated with a social Darwinist view of the world as a ruthlessly competitive jungle in which the strong win and the weak lose.

And third, the correlations between RWA and SDO scales suggest that they are substantially independent dimensions. Although some studies, notably in Western European countries, have reported strong positive correlations (e.g., Duriez & Van Hiel, 2002; Van Hiel & Miervelde, 2002), most research, and particularly that in North America, has found weak or nonsignificant correlations (see the reviews and meta-analyses by Duckitt, 2001 and Roccato & Ricolfi, 2005). Some studies, notably in ex-communist East European countries, have found nonsignificant or even significant negative

296 |

PERSONALITY AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES |

|

|

correlations between RWA and SDO (e.g., Duriez, Van Hiel, & Kossowska, 2005; Krauss, 2002; Van Hiel & Kossowska, 2007).

These findings indicate that, whereas SDO and RWA both predict attitudinal and behavioral phenomena associated with the political right as opposed to the left, they seem to be quite distinct and independent dimensions of ideological attitudes.

Earlier Research Supporting Two Dimensions

of Ideological Attitudes

The idea that there may be two distinct dimensions of ideological attitudes is not new. Although the unidimensional approach to ideological attitudes has been widely accepted until recently, over the years, many empirical investigations have found that socio-political attitudes and values were organized along two primary dimensions that seem to correspond very closely to RWA and SDO. The RWA-like dimension has been labelled authoritarianism, social conservatism, or traditionalism, at one pole, versus openness, autonomy, liberalism, or personal freedom at the other pole. The SDO-like dimension has been labelled economic conservatism, power, or belief in hierarchy and inequality at one pole versus egalitarianism, humanitarianism, or social welfare and concern at the other pole. These findings were reviewed earlier (Duckitt, 2001) and are summarized in Table 12.1, with several more recent investigations added (i.e., Ashton et al., 2005; Stangor & Leary, 2006).

Overall, therefore, a great deal of evidence from a large number of empirical investigations suggests that there seem to be two primary dimensions of socio-political or ideological attitudes and values. Although these investigations have used a variety of measures and terms for each of these two dimensions, recent research does suggest that RWA and SDO scales may be particularly strong and direct measures of them (Altemeyer, 1998, pp. 55–60, 1998; McFarland, 1998; McFarland, 2006). When RWA and SDO have been used together with other measures of these dimensions, they have invariably been the strongest and most consistent predictors of socio-political behaviors and reactions, possibly because RWA and SDO scales tap the crucial core aspects of these dimensions most directly, or because of their better psychometric properties and higher degree of unidimensionality.

Research Suggesting Differential Bases of RWA and SDO

If there are two distinct, often relatively orthogonal dimensions of ideological attitudes, it seems likely that these dimensions may express different motives or values and have different social and psychological bases. There is a good deal of evidence for this, and this has led to the formulation of a dual process cognitive-motivational model of ideology and social attitudes.

A Dual Process Motivational Model |

297 |

|

|

Table 12.1 Research indicating two primary ideological attitude or value dimensions.

Study |

RWA equivalent |

SDO equivalent |

Eysenck (1954) |

Conservatism vs. liberalism |

Tough vs. tender (humane vs. |

|

|

inhumane) (Brown, 1965) |

Tomkins (1964) |

Normative (conservatism) |

Humanism |

Hughes (1975) |

Social conservatism vs. |

Economic conservatism vs. |

|

liberalism |

social welfare |

Rokeach (1973) |

Freedom |

Equality |

Hofstede (1980) |

Collectivism vs. individualism |

Power distance |

Kerlinger (1984) |

Conservatism |

Liberalism (i.e., humanism- |

|

|

egalitarianism) |

Forsyth (1980) |

Relativism (i.e., group |

Idealism (altruism/social |

|

orientation) |

concern) |

Katz & Hass (1988) |

Protestant ethic |

Humanitarianism/ |

|

|

egalitarianism |

Middendorp (1991) |

Cultural conservatism vs. |

Economic conservatism |

|

openness |

vs. equality |

Trompenaars (1993) |

Group loyalty vs. individualism |

Hierarchy vs. egalitarianism |

Braithwaite (1994) |

National strength and order |

International harmony |

Schwartz (1996) |

Conservatism vs. openness |

Power vs. egalitarianism |

Triandis & Gelfand (1998) |

Collectivism vs. individualism |

Vertical vs. horizontal values |

Saucier (2000) |

Alpha-isms (conservatism- |

Beta-isms (SDO/ |

|

authoritarianism) |

Machiavellianism) |

Jost et al. (2003) |

Resistance to change |

Acceptance of inequality |

Ashton et al (2005) |

Moral regulation vs. individual |

Compassion vs. competition |

|

freedom |

|

Stangor & Leary (2006) |

Conservatism |

Egalitarianism |

|

|

|

First, research has linked RWA and SDO to different motives and values. Numerous studies using Schwartz’s (1992) well-validated values inventory (developed to measure universal values that express basic human motivational goals) have shown that the conservative values of security, conformity, and tradition correlate strongly with RWA but not with SDO, whereas power and self-enhancement values correlate with SDO but not with RWA (Altemeyer, 1998; Duriez & Van Hiel, 2002; Duriez, Van Hiel, & Kossowska, 2005; McFarland, 2006).

Second, research has also linked RWA and SDO to two very different sets of beliefs about the nature of the social world. For example, research by Altemeyer (1998) and others (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt et al., 2002) suggests that RWA, but not SDO, tends to be associated with a belief that the social world is dangerous and threatening. On the other hand, SDO, but not RWA,

298 |

PERSONALITY AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES |

|

|

was associated with measures such as Machiavellianism (Saucier, 2000), and Altemeyer’s (1998) “personal power, meanness, and dominance” and “exploitive manipulative, amoral, dishonesty” scales. These all tap a competitive, manipulative, cynical, social Darwinist view of the world.

And third, research has also found that RWA and SDO correlate with quite different personality traits. Heaven and Bucci (2001) found that RWA correlated with personality trait measures of dutifulness, orderliness, and moralism. This was consistent with Altemeyer’s (1998) earlier observation that persons high in RWA are self-righteous, conscientious, agreeable, and low on openness. These findings suggest a coherent trait pattern, which Duckitt (2001; Duckitt et al., 2002) captured in a single personality construct, refined from one of Saucier’s (1994) Big Five personality dimensions: social conformity. This social conformity scale included items such as obedient, respectful, and moralistic versus nonconforming, rebellious, and unpredictable, and correlated very strongly with RWA but not with SDO.

In contrast, studies have found SDO to be associated with low scores on personality measures of empathy, and high scores on Eysenck’s psychoticism scale (Altemeyer, 1998; McFarland, 1998; McFarland & Adelson, 1996), which is indicative of being tough-minded, unempathic, cold, and hostile (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). Heaven and Bucci (2001) similarly found that SDO was correlated with low scores on traits of sympathy, cooperation, agreeableness, and morality. Duckitt (2001) developed a tough versus tender-mindedness trait rating scale to capture this trait pattern, consisting of items such as tough-minded, hard-hearted, and uncaring versus sympathetic, compassionate, and forgiving, which correlated strongly with SDO but not with RWA.

Overall, therefore, a good deal of research suggested that RWA and SDO were associated with different motivational goals and values, and might be influenced by different social worldview beliefs and personality trait dimensions. These factors were therefore integrated in a dual process motivational model of the psychological bases of RWA and SDO (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt et al., 2002).

A DUAL PROCESS MOTIVATIONAL MODEL

The dual process motivational model proposes that RWA and SDO represent two basic dimensions of social or ideological attitudes, with each expressing motivational goals or values made chronically salient for individuals by their social worldviews and their personalities (Duckitt, 2001). High RWA expresses the motivational goal of establishing or maintaining societal security, order, cohesion, and stability, which is made salient for the individual by the schema-based worldview belief that the social world is

A Dual Process Motivational Model |

299 |

|

|

an inherently dangerous and threatening (as opposed to safe and secure) place. The predisposing personality dimension is social conformity (as opposed to autonomy), which leads individuals to identify with the existing social order, be more sensitive to threats to it, and so value order, stability, and security.

In contrast, SDO stems from the underlying personality dimension of tough versus tender-mindedness. Tough-minded personalities view the world as a ruthlessly competitive jungle in which the strong win and the weak lose, which makes salient the motivational goals of power, dominance, and superiority over others, which is then expressed in the social attitude of SDO.

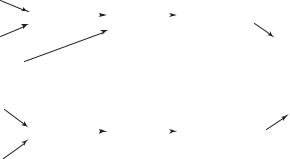

These two social worldviews should generally be relatively stable, reflecting the influence of individuals’ personality and socialization, but they should also be influenced by social situations. When the social world becomes markedly more dangerous and threatening, and is perceived as such, individuals’ attitudes should become more authoritarian. Social situations characterized by high levels of inequality and competition over power, status, and resources should cause individuals to see their social worlds as competitive jungles, and so cause stronger endorsement of social dominance attitudes. This causal model of how individuals’ personalities, their social situations, and their social worldview beliefs influence their ideological attitudes is summarized in Figure 12.1.

Social/group context: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Danger/threat |

Worldview: |

|

|

Ideological |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perceived |

||

|

Dangerous |

|

|

beliefs: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

social threats |

||

Personality: |

world beliefs |

|

|

RWA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Social conformity |

|

|

|

|

|

Legitimizing myths |

(low openness, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right-wing politics |

|

high conscientiousness) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Militarism |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nationalism |

Personality: |

|

|

|

|

|

Ethnocentrism |

|

|

|

|

|

Intolerance/prejudice |

|

Tough-mindedness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(low agreeableness) |

Worldview: |

|

|

Ideological |

|

Competitiveness |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Competitive |

|

|

beliefs: |

|

over relative |

|

|

|

|

|||

Social/group context: |

world beliefs |

|

|

SDO |

|

group |

|

|

|

|

|

superiority/power |

|

Resource scarcity, |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

inequality & competition |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 12.1 A causal model of the impact of the social situation, personality, and social worldviews on the two ideological attitude–value dimensions of right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) and social dominance orientation (SDO) and their impact on legitimizing myths, socio-political behavior, and attitudes as mediated through perceived social threat or competitiveness over dominance, power, and resources.

300 |

PERSONALITY AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES |

|

|

NEW RESEARCH ON THE PSYCHOLOGICAL

BASES OF RWA AND SDO

New research has also supported the dual process motivational model’s hypotheses about the different personality and worldview bases of RWA and SDO, as depicted in Figure 12.1. This evidence has been particularly compelling in the case of the personality bases of RWA and SDO, because this new research has used entirely different, but well-validated measures, and has obtained findings completely consistent with those initially reported.

The original test of the dual process model used somewhat ad hoc personality measures of social conformity and tough-mindedness, neither of which had been systematically validated. Both were, however, expected to be directly related to the Big Five personality dimensions, with social conformity expected to be strongly related to low openness to experience, and somewhat less strongly with high conscientiousness. Tough-mindedness was expected to be strongly related to low agreeableness. This was empirically confirmed with data from 259 New Zealand students. When the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP; Goldberg, 1999) Big Five measures were simultaneously regressed on tough-mindedness, the only significant, though very powerful, predictor was low agreeableness ( β = –.72, t = –15.23, p < .01). Social conformity, as expected, was predicted by low openness (β = –.39, t = –6.99, p < .01) and somewhat less strongly by high conscientiousness (β = .29, t = 5.36, p < .01), but also weakly by high agreeableness (β = .25, t = 4.50, p < .01).

This suggested that low agreeableness should predict SDO, and low openness, high conscientiousness, and perhaps high agreeableness should predict RWA. Findings from four recent studies that investigated the relationship of well-validated Big Five personality measures with RWA and SDO are summarized in Table 12.2. The averaged effects over these four studies were as expected. Low agreeableness was clearly associated with SDO, and controlling RWA did not affect this. Low openness was also associated with SDO, but this association was considerably reduced when controlling for RWA. Low openness and high conscientiousness were associated with RWA, and controlling for SDO did not alter these effects. High agreeableness was also associated with RWA, but only when controlling for the effect of SDO, suggesting that, once shared variance with SDO had been controlled, people high in agreeableness tend to be slightly more prone to RWA. No other partialed effects (necessary because of strong relationships between RWA and SDO in most of these studies) suggested notable or significant effects (in treating effects of .10 or greater as noteworthy).

These findings are therefore clearly consistent with those initially reported. They support the proposition that two very different sets of personality traits,

A Dual Process Motivational Model |

301 |

|

|

Table 12.2 Summary of bivariate and partial correlations between Big Five personality dimensions with SDO and RWA.

Source |

|

E |

A |

|

C |

|

N |

O |

|

|

ASSOCIATION WITH SDO (CONTROLLING FOR RWA) |

||||||

Akrami & Ekehammar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2006) (N = 332) |

|

–.03 (–.02) |

–.46 (–.47) |

.01 |

(–.04) |

–.06 (–.06) |

–.35 (–.20) |

|

Duriez & Soenens |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2006) (N = 320) |

|

–.01 (–.01) |

–.29 (–.31) |

.02 |

(–.12) |

–.04 (–.01) |

–.24 (–.12) |

|

Ekehammar et al. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2004) (N = 185) |

|

.03 (–.06) |

–.25 (–.34) |

.10 |

(–.04) |

–.12 (–.03) |

–.07 (.09) |

|

Heaven & Bucci |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2001) (N = 215) |

.07 (.08) |

–.42 (–.41) |

–.04 (–.11) |

.01 (.01) |

–.26 (–.13) |

|||

Mean effect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(N = 1 052) |

|

.01 (–.01) |

–.36* (–.39*) |

.02 |

(–.08) |

–.05 (–.03) |

–.25* (–.11*) |

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

|

ASSOCIATION WITH RWA (CONTROLLING FOR SDO) |

||||||

Akrami & Ekehammar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2006) (N = 332) |

–.03 (–.02) |

–.08 |

(.12) |

.11 |

(.12) |

–.01 (–.01) |

–.49 (–.41) |

|

Duriez & Soenens |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2006) (N = 320) |

.00 (.00) |

–.03 |

(.11) |

.29 |

(.31) |

–.07 (–.06) |

–.33 (–.26) |

|

Ekehammar et al. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2004) (N = 185) |

.15 (.16) |

.08 |

(.25) |

.25 |

(.23) |

–.18 (–.14) |

–.28 (–.29) |

|

Heaven & Bucci |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(2001) (N = 215) |

–.01 (–.04) |

–.11 |

(.06) |

.17 |

(.20) |

.00 (.00) |

–.40 (–.34) |

|

Mean effect |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(N = 1 052) |

.01 .(01) |

–.04 |

(.13*) |

.21* (.22*) |

–.06 (–.05) |

–.39* (–.33*) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note. * Mean effect size signifi cant at p < .001. Values in brackets represent partial correlations. Partial correlations between The Big Five and SDO controlled for RWA, whereas partial correla-

tions between The Big Five and RWA controlled for SDO, expressed as: r12.3 = (r12 – (r13 . r23)) / square root of (1 – r132)(1 – r232); r coeffi cients were transformed to z-scores using the formula:

zr = .5 loge ((1+r)/ (1–r)) then weighted by their inverse variance (n–3) and averaged before being converted back to r-values.

originally measured as social conformity and tough-mindedness, seem to underlie RWA and SDO. New research has also supported the dual process model’s proposal that two very different social worldview beliefs also differentially influence RWA and SDO.

Duckitt’s (2001) original research, which differentially linked dangerous world beliefs and competitive world beliefs with RWA and SDO, respectively, did so using cross-sectional data. Subsequent research has taken this