jost_j_t_kay_a_c_thorisdottir_n_social_and_psychological_bas

.pdf

112 |

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL POWER OF THE STATUS QUO |

|

|

consistent with our theoretical reasoning, attributions mediated this relation. Specifically, the stronger participants’ BJW, the less they relied on external attributions and the more they relied on internal attributions for their negative outcome (although the latter correlation was only marginally significant). These internal and external attributions were in turn related to higher or lower perceptions of fairness, respectively.

Experimentally induced negative outcomes (either of the participant or of a hypothetical third party) also tend to be interpreted by those with a strong BJW as more fair when compared with those with a weak BJW, overall or sometimes in interaction with moderator variables (e.g., Correia & Vala, 2003, Study 1; Hafer & Olson, 1989; Hagedoorn, Buunk, & Van de Vliert, 2002). In two such experimental studies, Hafer and Olson (1989) had participants complete a computer task that led to a negative outcome. Results from both experiments showed that a stronger BJW predicted higher ratings of the fairness of the experiment. In Study 1, this effect was most pronounced in the condition in which there were cues that participants were partly responsible for their deprivation because they chose the task that led to their negative outcome, a finding that was consistent with the notion that those with a strong BJW are often more likely to attribute negative outcomes to internal causes.

In summary, endorsement of a BJW, overall and sometimes in the face of explicit contradictions to a BJW, is associated with attributions and attitudes that increase the perceived deservingness of targets, and, thus, the perceived fairness of the situation. Increased perceptions of fairness add legitimacy to the situation and, thus, justify existing social circumstances. This analysis implies that a strong BJW can lead one to accept a situation that otherwise might appear illegitimate and unacceptable. One example of such a situation is group-based discrimination (i.e., negative treatment of people in a particular group that is based solely on their membership in that group). If individuals who strongly endorse a BJW tend to see situations as more fair (and, therefore, legitimate) compared to those who only weakly endorse a BJW, then a strong BJW might be related to less perceived discrimination, especially in the face of specific cues for discriminatory treatment. In the following section, we discuss the relation between individual differences in BJW and perceptions of discrimination, focusing on results from a recent study conducted in our own laboratory.

BELIEF IN A JUST WORLD AND PERCEPTIONS

OF DISCRIMINATION

Individual differences in BJW have been studied in the past with respect to general measures of discrimination. For example, stronger endorsement

Belief in a Just World |

113 |

|

|

of a BJW has been associated with decreased perceptions of discrimination against a variety of groups, including gays and lesbians in Toronto, Canada (Birt & Dion, 1987), racial groups in the United States (Neville, Lilly, Duran, Lee, & Brown, 2000), and women in the workforce in Europe (Dalbert et al., 1992). A few investigations have yielded a similar negative correlation between BJW and perceptions that one has personally been the victim of discrimination (Lipkus & Siegler, 1993; Major et al., 2002, cited in Major, Quinton, & McCoy, 2002).

Data from a larger experimental project on reactions to discrimination (Hafer, Crosby, Foster, & Choma, 2006) allowed us to expand on these previous investigations by examining people’s BJW and reactions to a specific act of discrimination directed toward them personally. We also tested whether the relation between individual differences in BJW and reported discrimination was moderated by a situational variable—the ambiguity of cues to discrimination (for a review, see Major et al., 2002). We operationally defined ambiguity in the present study in terms of the nature of available comparison information. Foster and Matheson (1995) argued that members of disadvantaged groups are more likely to perceive themselves as victims of group-based discrimination (and engage in collective action) if they not only see themselves as receiving lesser outcomes than outgroup members, but also believe that other members of their ingroup have similar experiences (see also Foster & Matheson, 1999). This argument implies that, although a member of a disadvantaged group might perceive negative outcomes resulting from a system that is biased against his group as ambiguously discriminatory, far less ambiguity should exist if the individual is exposed to other ingroup members who have experienced similar incidents.

In the present study, then, we manipulated the ambiguity of cues to discrimination by independently varying the presence of personal gender bias (i.e., gender bias experienced by the participant) and group gender bias (i.e., gender bias experienced by other members of the participant’s gender group). Essentially, female participants were given bogus failure feedback on a supposed cognitive ability test, an outcome they believed would lead to lesser prestige, comfort, and material resources than if their score on the test had been higher (for similar procedures, see, for example, Foster & Dion, 2003; Taylor, Wright, & Ruggiero, 1991). All participants were led to believe that the test was biased against women. The manipulations were achieved by varying whose scores supposedly received a standard adjustment for this bias. In the personal gender bias conditions, participants were led to believe that their own score would not be adjusted; in the no personal gender bias conditions, participants believed that their own score either had been or would be adjusted. In the group gender bias conditions, participants

114 |

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL POWER OF THE STATUS QUO |

|

|

were led to believe that the scores of other women in the study had not been adjusted; in the no group gender bias conditions, participants believed that the scores of other women in the study had been adjusted.

Crossing these two manipulations yielded four conditions: personal gender bias only, personal and group gender bias, group gender bias only, and no gender bias. Presumably, cues to personal discrimination in the absence of cues to discrimination against other ingroup members (i.e., the personal gender bias only condition) would make the presence of personal discrimination more ambiguous compared to a situation in which cues for sex discrimination are directed at both oneself and the rest of one’s group (i.e., the personal and group gender bias condition). The other two conditions (group gender bias only and no gender bias) can be considered control groups.

The primary dependent variable was a three-item measure of perceived personal discrimination (e.g., “To what extent was the procedure that was used discriminatory to you personally?,” “To what extent was the procedure that was used fair to you personally?”). A similar three-item measure of perceived group discrimination served as a check for the group gender bias manipulation. Both measures were collected, among other items, via an anonymous questionnaire. Individual differences in BJW (using Lipkus’s, 1991, Global Belief in a Just World Scale) and the related variables of political conservatism (self-placement from very liberal to very conservative) and belief in control (from Janoff-Bulman’s, 1989, World Assumptions Scale) were assessed in separate and earlier sessions. We expected that those with a strong BJW would report less discrimination than those with a weak BJW in the face of cues for personal discrimination. Furthermore, we expected this difference to occur especially when cues for personal discrimination were more ambiguous (i.e., in the personal gender bias only condition) than when they were less ambiguous (i.e., in the personal and group gender bias condition). We also tested whether results involving individual differences in BJW could be accounted for by political conservatism or beliefs about control (for a review of the relation between scores on just-world scales and these other individual differences, see Furnham & Procter, 1989).

Preliminary analyses showed that participants perceived the manipulation of group gender bias as anticipated. Participants reported more discrimination against women as a whole in the group gender bias conditions (M 2.62) than in the no group gender bias conditions (M 1.82).

To examine the role of BJW in perceived personal discrimination, we conducted an analysis of covariance with personal gender bias (present versus absent), group gender bias (present versus absent), and BJW (strong versus weak; based on a median split) as between-subject independent variables, and control beliefs as a covariate (because control beliefs were associated

Belief in a Just World |

115 |

|

|

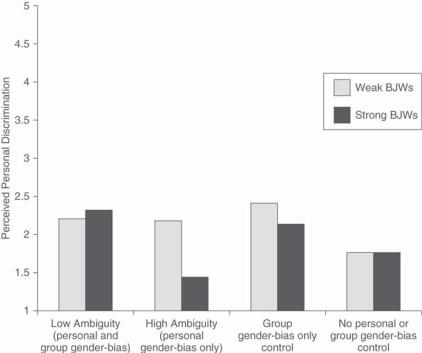

with perceived personal discrimination). This analysis yielded a significant three-way interaction (Figure 5.1). As expected, results showed that those with a strong BJW in the high-ambiguity (i.e., personal gender bias only) condition reported less perceived discrimination against them personally than did those with a weak BJW, whereas there was no significant difference between strong versus weak BJW in the low-ambiguity (i.e., personal and group gender bias) condition, nor in either of the control groups. Although the difference between those with a strong and weak BJW in the low-ambi- guity condition was nonsignificant, an interesting trend was noted for those with a strong BJW to report more personal discrimination than those with a weak BJW. This pattern is consistent with a few previous studies that suggest people scoring high on just-world scales could be more attuned to cues for justice and injustice (see Hagedoorn, Buunk, & Van de Vliert, 2002; Maes & Schmitt, 1999; Schmitt, Gollwitzer, Maes, & Arbach, 2005).

Our results could not be accounted for by the overlap between BJW and political conservatism or control beliefs. Although, as anticipated, individual

Figure 5.1 Interaction between personal gender bias, group sex bias, and belief in a just world on perceived personal discrimination. BJWs, believers in a just world.

116 |

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL POWER OF THE STATUS QUO |

|

|

differences on the just-world scale were significantly associated with greater political conservatism and stronger beliefs about control, results of analyses of variance with personal gender bias, group gender bias, and either political conservatism (strong versus weak) or control beliefs (strong versus weak), as between-subject variables showed no significant interaction effects involving the individual differences.

Our data add to previous research on BJW and perceived discrimination by offering evidence that those with a strong BJW can perceive less discrimination than those with a weak BJW within the context of a specific incidence of personally experienced discrimination, at least when the discriminatory nature, and therefore the fairness, of the situation is relatively ambiguous. The decreased perception of discrimination on behalf of people with a strong BJW would justify the given procedure or system, in that a system appearing to be nondiscriminatory and fair also seems justifiable and legitimate (see Tyler, 2006). Our data also show, however, that the system-justifying effect of a strong BJW did not extend to a less ambiguous case of personal discrimination, thus highlighting the importance of moderators in the link between certain beliefs and ideologies, and system justification. Finally, the effects summarized in our study were specific to individual differences in BJW, rather than being generalizable to other system-legitimizing variables (i.e., political conservatism, control beliefs).

To summarize our discussion thus far, in the first section of this chapter, we reviewed literature suggesting that a strong BJW is associated with justification of the existing social system, partly through attitudes and attributions that increase perceptions that people’s fate is deserved and, therefore, fair. In the second section, we discussed one implication of this system-justifying process—that a strong BJW might be associated with lesser perceived discrimination, overall and in specific situations, at least when those situations are ambiguous. We believe the information presented thus far anticipates several broader questions regarding moderators and mediators of the association between beliefs and ideologies (including BJW) and justification of the status quo. In the next section, we discuss these broader issues as well as ideas for future research.

MODERATORS AND MEDIATORS OF THE RELATION BETWEEN BELIEFS AND JUSTIFICATION

OF THE STATUS-QUO

Moderators and System-Justifying Beliefs

One moderator of the relation between beliefs and justification of the status quo appears to be the ambiguity of the situation. In our study of personal

Belief in a Just World |

117 |

|

|

discrimination, a stronger BJW was related to less perceived discrimination and unfairness, which presumably would justify the existing system. However, this association was moderated by the ambiguity of cues for personal discrimination, more specifically, by the nature of available comparison information. System-justifying effects of other beliefs might also be moderated by the ambiguity of situational cues—cues either for unfairness or for alternative indicators of system legitimacy (for alternative indicators, see the following section on mediators). For example, a study by Major and colleagues (2002, Study 2) showed that, among members of low-status groups, stronger endorsement of a belief in individual mobility (a presumably legitimizing ideology) was associated with reduced perceptions that negative outcomes were discriminatory. However, this relation only occurred when the negative outcome was delivered by an outgroup member, not when the outcome was delivered by a member of their ingroup. Perhaps negative outcomes from outgroup members are ambiguously discriminatory, whereas those from ingroup members are less ambiguous, in that they are seen as clearly nondiscriminatory. If so, the differential relation between low-status group members’ belief in individual mobility and their perceptions of discrimination might have been caused, as in our own research with BJW, by the moderating influence of situational ambiguity (for the moderating influence of ambiguity on the relation between group identification and attributions of discrimination and prejudice, see Major, Quinton, & Schmader, 2003; Operario & Fiske, 2001).

Moderators other than ambiguity of situational cues are also likely. In the same article by Major and colleagues (2002) for example, the status of one’s group moderated the relation between a belief in individual mobility and perceptions of discrimination (see Jost, Banaji, & Nosek, 2004 for a different moderating effect of group status in the context of the system-justifying ideology of political conservatism). The stronger the belief in individual mobility, the less members of low-status groups attributed negative outcomes delivered by an outgroup member to discrimination. Decreased perceptions of discrimination should help to justify the status quo. However, as we found for BJW, a belief in individual mobility was not always associated with a system-justifying perception. Among members of high-status groups, the stronger the belief in individual mobility, the more negative outcomes delivered by an outgroup member were attributed to discrimination, an attribution implying system illegitimacy. Both Major and colleagues’ (2002) and our own results suggest that we cannot assume all apparently system-justifying beliefs act as such across situations and individuals. We encourage researchers to investigate other moderator variables in the future.

118 |

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL POWER OF THE STATUS QUO |

|

|

Another point regarding moderator variables is that certain moderators may have varying effects depending on the particular belief being studied. For instance, consistent with the findings of our discrimination study, when cues to discrimination are less ambiguous, individual differences, such as in the strength of one’s BJW, may play less of a role in perceived discrimination than when cues are more ambiguous, perhaps because the strength of the situation overwhelms individual differences (see Snyder & Ickes, 1985). However, we also noted a nonsignificant trend in the low-ambiguity condition for those with a strong BJW to report more personal discrimination than those with a weak BJW. Beliefs other than BJW might show this alternative form of interaction more clearly.

Different moderators may also be relevant only for certain beliefs. In our own study, for example, individual differences in control beliefs were related to perceptions of personal discrimination. Our operationalization of the ambiguity of cues to discrimination, however, did not moderate the relation between control beliefs and the dependent variable. The varying relevance of moderator variables might, in part, be due to the specific mediating processes that serve to justify the status quo for different beliefs and ideologies. The issue of mediators between beliefs and system justification is discussed next.

Mediators and System-justifying Beliefs. We argue in this chapter that perceived fairness (as well as attributions and attitudes that increase perceptions of fairness) can mediate the relation between individual differences in BJW and system justification, in that a system that is perceived as fair seems legitimate and, therefore, in no need of change. Although fairness is probably one of the most common legitimizing perceptions, there are likely additional reasons for a system to seem legitimate and justified (see Tyler, 2006).

Alternative reasons for perceiving the status quo as justified may be more or less relevant to certain beliefs. For example, conservative political ideology, although sharing some variance with BJW and predicting to some similar attributions and attitudes toward victims (e.g., Skitka, 1999; Skitka et al., 2002), may implicate a process of system justification other than a tendency to see the world as fair. One alternative basis for system justification is tradition (Weber, 1968), in that a system may be seen as more legitimate if it involves longstanding conventions (see Feather, 2002). Conservatism, often characterized as a system-justifying ideology (e.g., Jost & Hunyady, 2005), is associated with a strong preference for tradition (e.g., Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, & Sulloway, 2003). Thus, a conservative ideology may justify the status quo, in part through its association with preference for tradition.

Another basis for legitimacy is authority. Social psychological research has repeatedly demonstrated the influence that a given authority figure can have

Belief in a Just World |

119 |

|

|

on the perceived legitimacy of requests, demands, rules, opinions, and the like emanating from that authority figure (e.g., Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973; Kelman & Hamilton, 1989; Milgram, 1974; Petty, Cacioppo, & Goldman, 1981; Raven, 2001). Individuals high in right-wing authoritarianism are especially prone to unquestioning acceptance of authority (e.g., Altemeyer, 1998). Thus, right-wing authoritarians may justify a current system through the legitimacy they place on the actions and opinions of authority figures (Altemeyer, 1988).

A third basis for justification of the status quo is religious doctrine. What is legitimate may be seen, for example, as whatever God has ordained as laid down in religious texts and taught by religious leaders. Individuals high in religious fundamentalism (see Altemeyer & Hunsberger, 1992) and related variables are especially prone to accepting such arguments as justifications of the status quo.

A final basis for justification of the status quo that we mention here (although others likely exist) is suggested by recent work by Kay and his colleagues (Jost & Kay, 2005; Kay & Jost, 2003; Kay et al., 2005)—perceived equality. These researchers have shown evidence that certain compensatory qualities attributed to “winners” and “losers” serve to justify the existing social system, apparently by ensuring a sense of equality or balance such that no one person or group has substantially more or less than another in society. Such compensatory attributions include, for example, “poor but happy” and “rich but unhappy” (Kay & Jost, 2003), as well as “unattractive but intelligent” and “attractive but unintelligent” (Kay et al., 2005). We wonder if this balanceor equality-based legitimacy is more likely for those with a liberal ideology or those low in social dominance orientation (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999), given that one of the key components of both is egalitarianism (Bobbio, 1996; Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Interestingly, Kay and Jost (2003) found that the effect of exposure to compensatory versus noncompensatory portrayals on a measure of system justification seemed to be greater for people who either weakly or strongly endorsed the Protestant work ethic, depending on the compensatory/noncompensatory trait used. Thus, aside from our suggestion that liberals or low social dominance people may justify the status quo partly through perceptions of equality and balance, certain kinds of balance may be more or less relevant to people high in other ideologies.

The various bases of legitimacy are surely often correlated with one another, as are the beliefs with which they are associated (e.g., Altemeyer, 1996; Crowson, Thoma, & Hestevold, 2005; Furnham & Procter, 1989), but it may be that the bases for justifying a system vary somewhat between beliefs. To the extent that this is true, it will be useful in the future to at times examine

120 |

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL POWER OF THE STATUS QUO |

|

|

system-justifying beliefs as separate entities (rather than incorporating several beliefs into a composite measure of a general system justifying ideology) and to do so within one study. Such an approach will help us to better understand varying processes of system justification.

CONCLUSION

We opened this chapter with examples in which a disadvantaged individual or group acts to maintain the status quo, even when the existing social system is not in their own best interests. One belief that might contribute to such behavior is a strong belief that the world is a just place in which people get what they deserve. A BJW might ultimately increase the perceived fairness of a given state of affairs. Perceived fairness would legitimate what might otherwise be considered an illegitimate and unjustifiable system. One implication of this process is that strong endorsement of a BJW can be associated with less perceived discrimination, even in the context of specific cues that one has personally been the target of group-based discrimination. A strong BJW, however, will not always be linked to such justification of the status quo. When unfairness (e.g., discrimination) is particularly unambiguous, for example, those with a strong BJW might report similar (or perhaps greater) degrees of injustice than will those with a weak BJW. Beliefs other than a BJW also contribute to system justification, and we suggest that alternative beliefs, although often related to one another, may have some unique moderators and mediators that indicate a different process of justification. Understanding these varying processes and the extent to which they do and do not co-occur is a challenge for future research on beliefs and justification of the status quo.

REFERENCES

Altemeyer, R. A. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Altemeyer, R. A. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Altemeyer, R. A. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality.” In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 47–91). New York: Academic Press.

Altemeyer, R. A., & Hunsberger, B. (1992). Authoritarianism, religious fundamentalism, quest, and prejudice. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 2, 113–133.

Ambrosio, A. L., & Sheehan, E. P. (1991). The just world belief and the AIDS epidemic. Journal of Social Behaviour and Personality, 6, 163–170.

Belief in a Just World |

121 |

|

|

Appelbaum, L. D. (2002). Who deserves help? Students’ opinions about the deservingness of different groups living in Germany to receive aid. Social Justice Research, 15, 201–225.

Ball, G. A., Trevino, L. K., & Sims, H. P. (1994). Just and unjust punishment: Influences on subordinate performance and citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 299–322.

Bègue, L., & Bastounis, M. (2003). Two spheres of belief in justice: Extensive support for the bidimensional model of belief in a just world. Journal of Personality, 71, 435–463.

Birt, C. M., & Dion, K. L. (1987). Relative deprivation theory and responses to discrimination in a gay male and lesbian sample. British Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 139–145.

Bobbio, N. (1996). Left and right. Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Campbell, D., Carr, S. C., & MacLachlan, M. (2001). Attributing “third world poverty” in Australia and Malawi: A case of donor bias? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31, 409–430.

Correia, I., & Vala, J. (2003). When will a victim be secondarily victimized? The effect of observer’s belief in a just world, victim’s innocence and persistence of suffering. Social Justice Research, 16, 379–400.

Cozzarelli, C., Wilkinson, A. V., & Tagler, M. J. (2001). Attitudes toward the poor and attributions for poverty. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 207–227.

Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 882–894.

Crandall, C. S., & Martinez, R. (1996). Culture, ideology, and anti-fat attitudes.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 1165–1176.

Crosby, F. (1982). Relative deprivation and working women. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crowson, H. M., Thoma, S. J., & Hestevold, N. (2005). Is political conservatism synonymous with authoritarianism? Journal of Social Psychology, 145, 571–592.

Dalbert, C. (2001). The justice motive as a personal resource: Dealing with challenges and critical life events. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Dalbert, C., Fisch, U., & Montada, L. (1992). Is inequality unjust? Evaluating women’s career chances. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée, 42, 11–17.

Dalbert, C., & Maes, J. (2002). Belief in a just world as a personal resource in school. In M. Ross & D. T. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 365–381). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dalbert, C., & Sallay, H. (Eds.). (2004). The justice motive in adolescence and young adulthood: Origins and consequences. New York: Routledge.

De Judicibus, M., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Blaming the target of sexual harassment: Impact of gender role, sexist attitudes, and work role. Sex Roles, 44, 401–417.

Dion, K. L., & Dion, K. K. (1987). Belief in a just world and physical attractiveness stereotyping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 775–780.

Drolet, M. (2002). The “who, what, when, and where” of gender pay differentials. (Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 71–584-MIE, no. 4).