- •Lecture 2 definitions of translation. Language, culture and thought definitions of translation

- •Language, culture and thought

- •Lecture 3

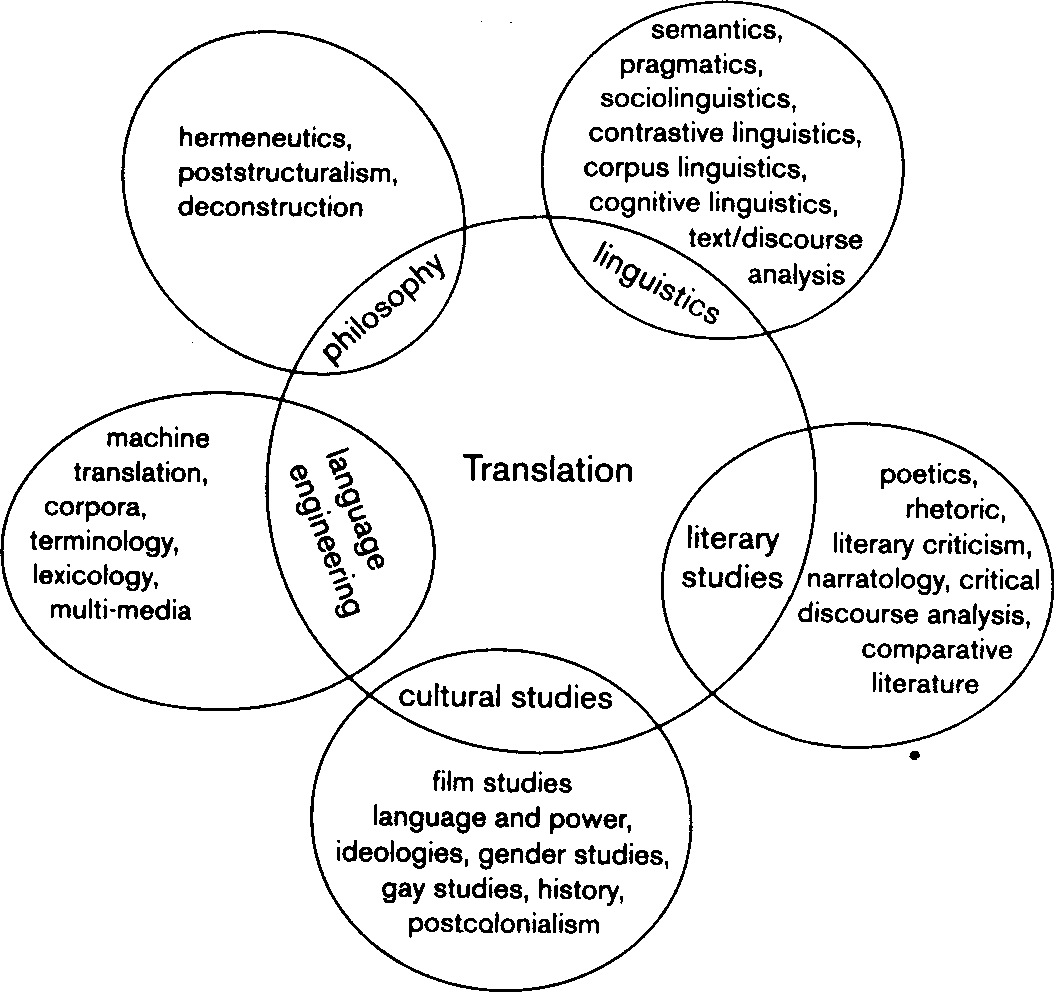

- •Interlingual, intralingual and intersemiotic translation

- •Map of disciplines interfacing with Translation Studies

- •Lecture 4 translation strategies

- •Lecture 5 systematic approaches to the translation unit

- •It acknowledged that childhood is a complex, evolving reality and that it merits now a specific consideration. The child is a fragile being, but his autonomy should not therefore be disregarded…

- •Lecture 6 translation shifts

- •The lexicon;

- •Lecture 7 the analysis of meaning

- •Надеяться

- •Lecture 8

Map of disciplines interfacing with Translation Studies

The richness of the field is also illustrated by areas for research, which include:

1. Text analysis and translation.

2. Translation quality assessment.

3. Translation of literary and other genres.

4. Multi-media translation (audiovisual translation).

5. Translation and technology.

6. Translation history.

7. Translation ethics.

8. Terminology and glossaries.

9. The translation process.

10. Translator training.

11. The characteristics of the translation profession.

This first unit has discussed what we mean by ‘translation’ and ‘Translation Studies’. It has built on Jakobson’s term ‘interlingual translation’ and Holmes’s mapping of the field of Translation Studies. In truth, we are talking of an interdiscipline, interfacing with a vast breadth of knowledge, which means that research into translation is possible from many different angles, from scientific to literary, cultural and political. A threefold scope of translation has been presented, with a goal of describing the translation process and identifying trends, if not laws or universals, of translation.

Lecture 4 translation strategies

If we were to sample what people generally take ‘translation’ to be, the consensus would most probably be for a view of translating that describes the process in terms of such features as the literal rendering of meaning, adherence to form, and emphasis on general accuracy. These observations would certainly be true of what translators do most of the time and of the bulk of what gets translated. These statements require much refinement and betray a strongly prescriptive attitude to translation, but they are also the product of some of the central issues of translation theory all the way from Roman times to the mid-twentieth century.

FORM AND CONTENT

Roman Jakobson makes the crucial claim that ‘all cognitive experience and its classification is conveyable in any existing language’. So, to give an example, while modern British English concepts such as the National Health Service, public-private partnership and congestion charging, or, in the USA, Ivy League universities, Homeland Security and speed dating, might not exist in a different culture, that should not stop them being expressed in some way in the target language (TL). R. Jakobson goes on to claim that only poetry ‘by definition is untranslatable’ since in verse the form of words contributes to the construction of the meaning of the text. Such statements express a classical dichotomy in translation between sense/content on the one hand and form/style on the other.

sense/ <———————————————> form/

content style

The sense may be translated, while the form often cannot. The point where form begins to contribute to sense is where we approach untranslatability. This clearly is most likely to be in poetry, song, advertising, punning and so on, where sound and rhyme and double meaning are unlikely to be recreated in the TL.

The spoken or written form of names in the Harry Potter books often contributes to their meaning. In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, one of the evil characters goes by the name of Tom Marvolo Riddle, yet this name is itself a riddle, since it is an anagram of ‘I am Lord Voldemort’ and reveals the character’s true identity. In the published translations, many of the Harry Potter translators have resorted to altering the original name in order to create the required pun: in French, the name becomes ‘Tom Elvis Jedusor’ which gives ‘Je suis Voldemort’ as well as suggesting an enigmatic fate with the use of the name Elvis and the play on words ‘jeudusor’ or ‘yeu du sort’, meaning ‘game of fate’. In this way the French translator has preserved the content by altering the form.

LITERAL AND FREE

The split between form and content is linked in many ways to the major polar split, which has marked the history of western translation theory for two thousand years, between two ways of translating: ‘literal’ and ‘free’. The origin of this separation k to be found in two of the most-quoted names in translation theory, the Roman lawyer and writer Cicero and St. Jerome, who translated the Greek Septuagint gospels into Latin in the fourth century. In Classical times, it was normal for translators working from Greek to provide a literal, word-for-word translation, which would serve as an aid to the Latin reader who, it could be assumed, was reasonably acquainted with the Greek source language. Cicero, describing his own translation of Attic orators in 46 вс, emphasized that he did not follow the literal word-for-word approach but, as an orator, ‘sought to preserve the general style and force of the language’.

Four centuries later, St. Jerome described his Bible translation strategy as ‘I render not word-for-word but sense for sense’. This approach was of particular importance for the translation of such sensitive texts as the Bible, deemed by many to be the repository of truth and the word of God. A translator who did not remain ‘true’ to the ‘official’ interpretation of that word often ran a considerable risk. Sometimes, as in the case of the sixteenth-century English Bible translator William Tyndale, it was the mere act of translation into the vernacular that led to persecution and execution.

The literal and free translation strategies can still be seen in texts to the present day.

A literal translation is not so common when the languages in question are more distant. Or, to put it another way, the term ‘literal’ has tended to be used with a different focus, sometimes to denote a TT which is overly close or influenced by the ST or SL. The result is what is sometimes known as translationese (an alternative name, translates).

Translationese is “a pejorative general term for the language of translation. It is often used to indicate a stilted form of the TL from calquing ST lexical or syntactic patterning. Translationese is related to translation universals since the characteristics mentioned above may be due to common translation phenomena such as interference, explicitation and domestication.

To illustrate this, let us consider some typical examples of translated material (the English TTs of Arabic STs) which seem to defy comprehension. As you read through these TTs, try to identify features of the texts that strike you as odd, and reflect on whether problems of this kind are common in languages you are familiar with. For example, what are we to make of the request for donations in this welfare organization’s publicity leaflet?

Example:

Honorable Benefactor,

The organization hopefully appeals to you, whether nationals or expatriates in (his generous country, to extend a helping hand....

We have the honor to offer you the chance to contribute to our programs and projects from your monies and alms so that God may bless you.

In this example of what in English would be a fund-raising text, confusion sets in when ‘making a donation’ is seen as an honor bestowed both on the donor and on those making the appeal. There is a certain opaqueness and far too much power for a text of this kind to function properly in English.

In a way, this is not different from the advert for a French wine purchasing company, which, instead of simply saying ‘Now you too can take advantage of this wonderful opportunity’, actually had: Today, we offer you to share this position.

In all these examples, the influence of poor literal translation is all too obvious. In this respect, perhaps no field has been more challenging to translators than advertising.

The concept of literalness that emerges from these examples is one of exaggeratedly close adherence on the part of the translator to the lexical and syntactic properties of the ST. Yet, once again, the literal-free divide is not so much a pair of fixed opposites as a cline:

literal <———————————————————>free

Different parts of a text may be positioned at different points on the dine, while other variables, as we shall see in the coming units, are text type, audience, purpose as well as the general translation strategy of the translator.

COMPREHENSIBILITY AND TRANSLATABILITY

Such literal translations often fail to take account of one simple fact of language and translation, namely that not all texts or text users are the same. Not all texts are as «serious» as the Bible or the works of Dickens, nor are they all as ‘pragmatic’ as marriage certificates or instructions on a medicine bottle. Similarly, not all text receivers are as intellectually rigorous or culturally aware as those who read the Bible or Dickens, nor are they all as ‘utilitarian’ as those who simply use translation as a means of getting things done. Ignoring such factors as text type, audience or purpose of translation has invariably led to the rather pedantic form of literalism, turgid adherence to form and almost total obsession with accuracy often encountered in the translations we see or hear day in day out. We have all come across translations, where the vocabulary of a given language may well be recognizable and the grammar intact, but the sense is quite lacking.

The problem with many published TTs of the kind cited earlier is essentially one of impaired ‘comprehensibility’, an issue closely related to ‘translatability’. Translatability is a relative notion and has to do with the extent to which, despite obvious differences in linguistic structure (grammar, vocabulary, etc.), meaning can still be adequately expressed across languages. But, for this to be possible, meaning has to be understood not only in terms of what the ST contains, but also equally significantly, in terms of such factors as communicative purpose, target audience and purpose of translation. This must go hand in hand with the recognition that, while there will always be entire chunks of experience and some unique ST values that will simply defeat our best efforts to convey them across cultural and linguistic boundaries, translation is always possible and cultural gaps are in one way or another bridgeable. To achieve this, an important criterion to heed must be TT comprehensibility.

Is everything translatable? The answer, to paraphrase Jakobson, is ‘yes, to a certain extent’. In the more idiomatic renderings provided above, the target reader may well have been deprived of quite a hefty chunk of ST meaning. But what choice does the translator have? Such insights as ‘it is an honor both to appeal for and to give to charity, both to issue and to accept an invitation, both to offer and to accept a glass of wine, both to live and to die, etc.’ are no doubt valuable. But what is the point in trying to preserve them in texts like fund-raising leaflets, adverts or political speeches if they are not going to be appreciated for what they are, i.e. if they do not prove to be equally significant to a target reader?

It is indeed a pity that the target reader of the modern Bible has to settle for to make somebody ashamed of his behavior, when the Hebrew ST actually has ‘to heap coal of fire on his head’ (Nida, 1969), with the ultimate aim, we suggest, not so much of burning his head as blackening his face which in both Hebrew and Arab-Islamic cultures symbolizes unspeakable shame. But how obscure is one allowed to be in order to live up to the unrealistic ideal of full translatability? Some of the main issues of translation are linked to the strategies of literal and free translation, form and content. This division, that has marked translation for centuries, can help identify the problems of certain overly literal translations that impair comprehensibility. However, the real underlying problems of such translations lead us into areas such as text type and audience.