Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

pulse pressure, and bradycardia may signal increasing intracranial pressure (ICP). If possible, elevate the patient’s head 30 degrees to decrease ICP, and attempt to keep his head straight and facing forward.

Evaluate the patient’s respiratory status, and be prepared to administer oxygen, insert an artificial airway, or provide intubation and mechanical ventilation, as needed. To help determine the nature of the patient’s injury, ask him for an account of the precipitating events. If he can’t respond, try to find an eyewitness.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient is in no immediate danger, perform a complete neurologic assessment. Start with the history, relying on family members for information if necessary. Ask about the onset, duration, intensity, and progression of paralysis and about the events preceding its development. Focus medical history questions on the incidence of degenerative neurologic or neuromuscular disease, recent infectious illness, sexually transmitted disease, cancer, or recent injury. Explore related signs and symptoms, noting fevers, headaches, vision disturbances, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, bowel or bladder dysfunction, muscle pain or weakness, and fatigue.

Next, perform a complete neurologic examination, testing cranial nerve (CN), motor, and sensory function and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). Assess strength in all major muscle groups, and note muscle atrophy. (See Testing Muscle Strength , pages 488 and 489.) Document all findings to serve as a baseline.

Medical Causes

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS is an invariably fatal disorder that produces spastic or flaccid paralysis in the body’s major muscle groups, eventually progressing to total paralysis. Earlier findings include progressive muscle weakness, fasciculations, and muscle atrophy, usually beginning in the arms and hands. Cramping and hyperreflexia are also common. Involvement of respiratory muscles and the brain stem produces dyspnea and possibly respiratory distress. Progressive cranial nerve paralysis causes dysarthria, dysphagial drooling, choking, and difficulty chewing.

Bell’s palsy. Bell’s palsy, a disease of CN VII, causes transient, unilateral facial muscle paralysis. The affected muscles sag, and eyelid closure is impossible. Other signs include increased tearing, drooling, and a diminished or absent corneal reflex.

Botulism. Botulism is a bacterial toxin infection that can cause rapidly descending muscle weakness that progresses to paralysis within 2 to 4 days after the ingestion of contaminated food. Respiratory muscle paralysis leads to dyspnea and respiratory arrest. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blurred or double vision, bilateral mydriasis, dysarthria, and dysphagia are some early findings.

Brain abscess. Advanced abscess in the frontal or temporal lobe can cause hemiplegia accompanied by other late findings, such as ocular disturbances, unequal pupils, a decreased LOC, ataxia, tremors, and signs of infection.

Brain tumor. A tumor affecting the motor cortex of the frontal lobe may cause contralateral hemiparesis that progresses to hemiplegia. The onset is gradual, but paralysis is permanent without treatment. In early stages, a frontal headache and behavioral changes may be the only

indicators. Eventually, seizures, aphasia, and signs of increased ICP (a decreased LOC and vomiting) develop.

Conversion disorder. Hysterical paralysis, a classic symptom of conversion disorder, is characterized by the loss of voluntary movement with no obvious physical cause. It can affect any muscle group, appears and disappears unpredictably, and may occur with histrionic behavior (manipulative, dramatic, vain, irrational) or a strange indifference.

Encephalitis. Variable paralysis develops in the late stages of encephalitis. Earlier signs and symptoms include a rapidly decreasing LOC (possibly coma), a fever, a headache, photophobia, vomiting, signs of meningeal irritation (nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs), aphasia, ataxia, nystagmus, ocular palsies, myoclonus, and seizures.

Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome is characterized by a rapidly developing, but reversible, ascending paralysis. It commonly begins as leg muscle weakness and progresses symmetrically, sometimes affecting even the cranial nerves, producing dysphagia, nasal speech, and dysarthria. Respiratory muscle paralysis may be life threatening. Other effects include transient paresthesia, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and bowel and bladder incontinence.

Head trauma. Cerebral injury can cause paralysis due to cerebral edema and increased ICP. The onset is usually sudden. The location and extent vary, depending on the injury. Associated findings also vary, but include a decreased LOC; sensory disturbances, such as paresthesia and loss of sensation; a headache; blurred or double vision; nausea and vomiting; and focal neurologic disturbances.

Multiple sclerosis (MS). With MS, paralysis commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Its extent can range from monoplegia to quadriplegia. In most patients, vision and sensory disturbances (paresthesia) are the earliest symptoms. Later findings are widely variable and may include muscle weakness and spasticity, nystagmus, hyperreflexia, an intention tremor, gait ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, impotence, and constipation. Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence may also occur.

Myasthenia gravis. With myasthenia gravis, profound muscle weakness and abnormal fatigability may produce paralysis of certain muscle groups. Paralysis is usually transient in early stages, but becomes more persistent as the disease progresses. Associated findings depend on the areas of neuromuscular involvement; they include weak eye closure, ptosis, diplopia, lack of facial mobility, dysphagia, nasal speech, and frequent nasal regurgitation of fluids. Neck muscle weakness may cause the patient’s jaw to drop and his head to bob. Respiratory muscle involvement can lead to respiratory distress — dyspnea, shallow respirations, and cyanosis.

Parkinson’s disease. Tremors, bradykinesia, and lead-pipe or cogwheel rigidity are the classic signs of Parkinson’s disease. Extreme rigidity can progress to paralysis, particularly in the extremities. In most cases, paralysis resolves with prompt treatment of the disease.

Peripheral neuropathy. Typically, peripheral neuropathy produces muscle weakness that may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy. Related effects include paresthesia, a loss of vibration sensation, hypoactive or absent DTRs, neuralgia, and skin changes such as anhidrosis.

Rabies. Rabies is an acute disorder that produces progressive flaccid paralysis, vascular collapse, coma, and death within 2 weeks of contact with an infected animal. Prodromal signs and symptoms — a fever; a headache; hyperesthesia; paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the bite site; photophobia; tachycardia; shallow respirations; and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration — develop almost immediately. Within 2 to 10 days, a phase of excitement

begins, marked by agitation, cranial nerve dysfunction (pupil changes, hoarseness, facial weakness, ocular palsies), tachycardia or bradycardia, cyclic respirations, a high fever, urine retention, drooling, and hydrophobia.

Seizure disorders. Seizures, particularly focal seizures, can cause transient local paralysis (Todd’s paralysis). Any part of the body may be affected, although paralysis tends to occur contralateral to the side of the irritable focus.

Spinal cord injury. Complete spinal cord transection results in permanent spastic paralysis below the level of injury. Reflexes may return after spinal shock resolves. Partial transection causes variable paralysis and paresthesia, depending on the location and extent of injury. (See

Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes.)

Spinal cord tumors. Paresis, pain, paresthesia, and variable sensory loss may occur along the nerve distribution pathway served by the affected cord segment. Eventually, these symptoms may progress to spastic paralysis with hyperactive DTRs (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, perhaps, bladder and bowel incontinence. Paralysis is permanent without treatment.

Stroke. A stroke involving the motor cortex can produce contralateral paresis or paralysis. The onset may be sudden or gradual, and paralysis may be transient or permanent. Associated signs and symptoms vary widely and may include a headache, vomiting, seizures, a decreased LOC and mental acuity, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, contralateral paresthesia or sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, vision disturbances, emotional lability, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is a potentially life-threatening disorder that can produce sudden paralysis. The condition may be temporary, resolving with decreasing edema, or permanent, if tissue destruction has occurred. Other acute effects are a severe headache, mydriasis, photophobia, aphasia, a sharply decreased LOC, nuchal rigidity, vomiting, and seizures.

Syringomyelia. Syringomyelia is a degenerative spinal cord disease that produces segmental paresis, leading to flaccid paralysis of the hands and arms. Reflexes are absent, and loss of pain and temperature sensation is distributed over the neck, shoulders, and arms in a capelike pattern. Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Episodic TIAs may cause transient unilateral paresis or paralysis accompanied by paresthesia, blurred or double vision, dizziness, aphasia, dysarthria, a decreased LOC, and other site-dependent effects.

West Nile encephalitis. West Nile encephalitis is a brain infection that’s caused by West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne Flavivirus endemic to Africa, the Middle East, western Asia, and the United States. Mild infections are common and include a fever, a headache, and body aches, which are sometimes accompanied by a skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infections are marked by a headache, a high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional seizures, paralysis and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

Drugs. The therapeutic use of neuromuscular blockers, such as pancuronium or curare, produces paralysis.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). ECT can produce acute, but transient, paralysis.

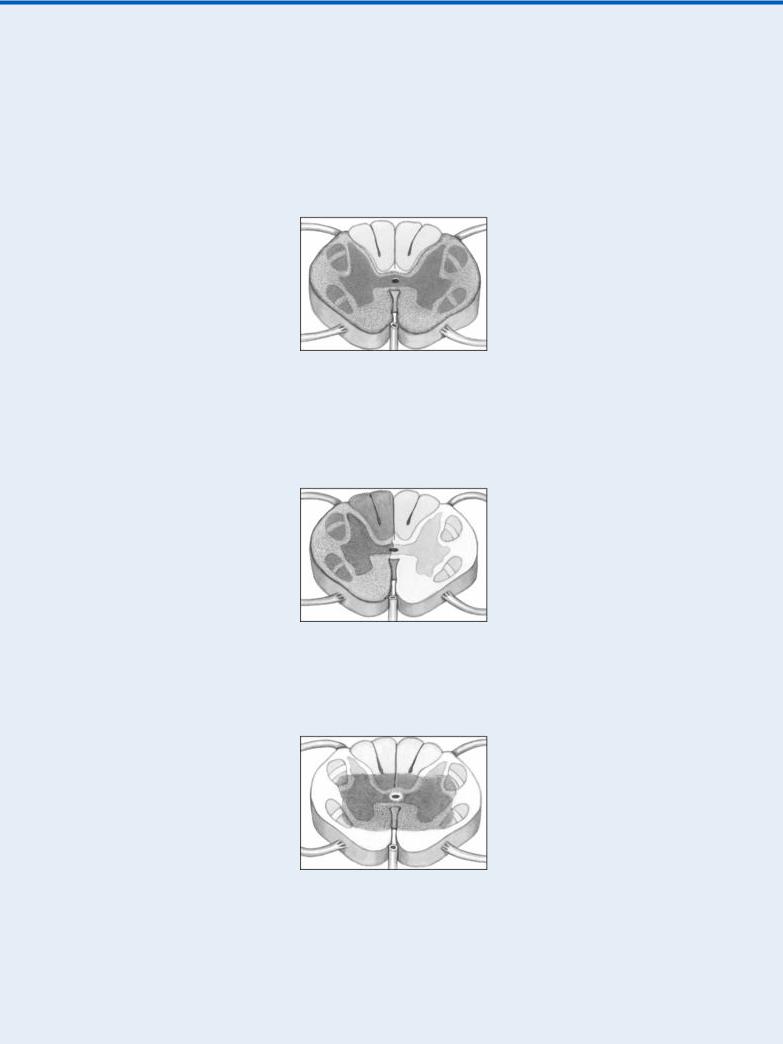

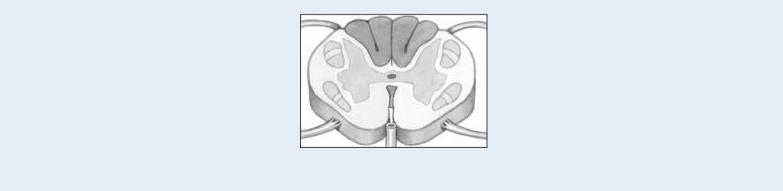

Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes

When a patient’s spinal cord is incompletely severed, he experiences partial motor and sensory loss. Most incomplete cord lesions fit into one of the syndromes described below.

Anterior cord syndrome, usually resulting from a flexion injury, causes motor paralysis and loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury. Touch, proprioception, and vibration sensation are usually preserved.

Brown-Séquard syndrome can result from flexion, rotation, or penetration injury. It’s characterized by unilateral motor paralysis ipsilateral to the injury and a loss of pain and temperature sensation contralateral to the injury.

Central cord syndrome is caused by hyperextension or flexion injury. Motor loss is variable and greater in the arms than in the legs; sensory loss is usually slight.

Posterior cord syndrome, produced by a cervical hyperextension injury, causes only a loss of proprioception and light touch sensation. Motor function remains intact.

Special Considerations

Because a paralyzed patient is particularly susceptible to complications of prolonged immobility, provide frequent position changes, meticulous skin care, and frequent chest physiotherapy. He may benefit from passive range-of-motion exercises to maintain muscle tone, the application of splints to prevent contractures, and the use of footboards or other devices to prevent footdrop. If his cranial nerves are affected, the patient will have difficulty chewing and swallowing. Provide a thickened liquid or soft diet, and keep suction equipment on hand in case aspiration occurs. Feeding tubes or total parenteral nutrition may be necessary with severe paralysis. Paralysis and accompanying vision disturbances may make ambulation hazardous; provide a call light, and show the patient how to call for help. As appropriate, arrange for physical, speech, swallowing, or occupational therapy.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the paralysis; provide referrals to social and psychological services. Teach the patient and family how to provide care at home, including passive range-of-motion exercises, frequent turning, and chest physiotherapy.

Pediatric Pointers

Although children may develop paralysis from an obvious cause — such as trauma, infection, or a tumor — they may also develop it from a hereditary or congenital disorder, such as Tay-Sachs disease, Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, spina bifida, or cerebral palsy.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sarwark, J. F. (2010). Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Paresthesia

Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation or combination of sensations — commonly described as numbness, prickling, or tingling — felt along peripheral nerve pathways; these sensations generally

aren’t painful. Unpleasant or painful sensations, on the other hand, are termed dysesthesias. Paresthesia may develop suddenly or gradually and may be transient or permanent.

A common symptom of many neurologic disorders, paresthesia may also result from a systemic disorder or particular drug. It may reflect damage or irritation of the parietal lobe, thalamus, spinothalamic tract, or spinal or peripheral nerves — the neural circuit that transmits and interprets sensory stimuli.

History and Physical Examination

First, explore the paresthesia. When did abnormal sensations begin? Have the patient describe their character and distribution. Also, ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as sensory loss and paresis or paralysis. Next, take a medical history, including neurologic, cardiovascular, metabolic, renal, and chronic inflammatory disorders, such as arthritis or lupus. Has the patient recently sustained a traumatic injury or had surgery or an invasive procedure that may have damaged peripheral nerves?

Focus the physical examination on the patient’s neurologic status. Assess his level of consciousness (LOC) and cranial nerve function. Test muscle strength and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in limbs affected by paresthesia. Systematically evaluate light touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and position sensation. (See Testing for Analgesia, pages 42 and 43.) Also, note skin color and temperature, and palpate pulses.

Medical Causes

Arterial occlusion (acute). With acute arterial occlusion, sudden paresthesia and coldness may develop in one or both legs with a saddle embolus. Paresis, intermittent claudication, and aching pain at rest are also characteristic. The extremity becomes mottled with a line of temperature and color demarcation at the level of occlusion. Pulses are absent below the occlusion, and the capillary refill time is increased.

Arteriosclerosis obliterans. Arteriosclerosis obliterans produces paresthesia, intermittent claudication (most common symptom), diminished or absent popliteal and pedal pulses, pallor, paresis, and coldness in the affected leg.

Arthritis. Rheumatoid or osteoarthritic changes in the cervical spine may cause paresthesia in the neck, shoulders, and arms. The lumbar spine occasionally is affected, causing paresthesia in one or both legs and feet.

Brain tumor. Tumors affecting the sensory cortex in the parietal lobe may cause progressive contralateral paresthesia accompanied by agnosia, apraxia, agraphia, homonymous hemianopsia, and a loss of proprioception.

Buerger’s disease. With Buerger’s disease, a smoking-related inflammatory occlusive disorder, exposure to cold makes the feet cold, cyanotic, and numb; later, they redden, become hot, and tingle. Intermittent claudication, which is aggravated by exercise and relieved by rest, is also common. Other findings include weak peripheral pulses, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis and, later, ulceration, muscle atrophy, and gangrene.

Diabetes mellitus. Diabetic neuropathy can cause paresthesia with a burning sensation in the hands and legs. Other findings include insidious, permanent anosmia, fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and polyphagia.

Guillain-Barré syndrome. With Guillain-Barré syndrome, transient paresthesia may precede muscle weakness, which usually begins in the legs and ascends to the arms and facial nerves. Weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other findings include dysarthria, dysphagia, nasal speech, orthostatic hypotension, bladder and bowel incontinence, diaphoresis, tachycardia and, possibly, signs of life-threatening respiratory muscle paralysis.

Head trauma. Unilateral or bilateral paresthesia may occur when head trauma causes a concussion or contusion; however, sensory loss is more common. Other findings include variable paresis or paralysis, a decreased LOC, a headache, blurred or double vision, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and seizures.

Herniated disk. Herniation of a lumbar or cervical disk may cause an acute or a gradual onset of paresthesia along the distribution pathways of affected spinal nerves. Other neuromuscular effects include severe pain, muscle spasms, and weakness that may progress to atrophy unless herniation is relieved.

Herpes zoster. An early symptom of herpes zoster, paresthesia occurs in the dermatome supplied by the affected spinal nerve. Within several days, this dermatome is marked by a pruritic, erythematous, vesicular rash associated with sharp, shooting, or burning pain.

Hyperventilation syndrome. Usually triggered by acute anxiety, hyperventilation syndrome may produce transient paresthesia in the hands, feet, and perioral area, accompanied by agitation, vertigo, syncope, pallor, muscle twitching and weakness, carpopedal spasm, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Migraine headache. Paresthesia in the hands, face, and perioral area may herald an impending migraine headache. Other prodromal symptoms include scotomas, hemiparesis, confusion, dizziness, and photophobia. These effects may persist during the characteristic throbbing headache and continue after it subsides.

Multiple sclerosis (MS). With MS, demyelination of the sensory cortex or spinothalamic tract may produce paresthesia — typically one of the earliest symptoms. Like other effects of MS, paresthesia commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Associated findings include muscle weakness, spasticity, and hyperreflexia.

Peripheral nerve trauma. Injury to a major peripheral nerve can cause paresthesia — commonly dysesthesia — in the area supplied by that nerve. Paresthesia begins shortly after trauma and may be permanent. Other findings are flaccid paralysis or paresis, hyporeflexia, and variable sensory loss.

Peripheral neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy can cause progressive paresthesia in all extremities. The patient also commonly displays muscle weakness, which may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy, a loss of vibration sensation, diminished or absent DTRs, neuralgia, and cutaneous changes, such as glossy, red skin and anhidrosis.

Rabies. Paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the site of an animal bite herald the prodromal stage of rabies. Other prodromal signs and symptoms are a fever, a headache, photophobia, hyperesthesia, tachycardia, shallow respirations, and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration.

Raynaud’s disease. Exposure to cold or stress makes the fingers turn pale, cold, and cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. Ulceration may occur in chronic cases. Seizure disorders. Seizures originating in the parietal lobe usually cause paresthesia of the lips, fingers, and toes. The paresthesia may act as auras that precede tonic-clonic seizures.

Spinal cord injury. Paresthesia may occur in partial spinal cord transection, after spinal shock resolves. It may be unilateral or bilateral, occurring at or below the level of the lesion. Associated sensory and motor loss is variable. (See Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes , page 555.) Spinal cord disorders may be associated with paresthesia on head flexion (Lhermitte’s sign).

Spinal cord tumors. Paresthesia, paresis, pain, and sensory loss along nerve pathways served by the affected cord segment result from such tumors. Eventually, paresis may cause spastic paralysis with hyperactive DTRs (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, possibly, bladder and bowel incontinence.

Stroke. Although contralateral paresthesia may occur with stroke, sensory loss is more common. Associated features vary with the artery affected and may include contralateral hemiplegia, a decreased LOC, and homonymous hemianopsia.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE may cause paresthesia, but its primary signs and symptoms include nondeforming arthritis (usually of the hands, feet, and large joints), photosensitivity, and a “butterfly rash” that appears across the nose and cheeks.

Tabes dorsalis. With tabes dorsalis, paresthesia — especially of the legs — is a common, but late, symptom. Other findings include ataxia, loss of proprioception and pain and temperature sensation, absent DTRs, Charcot’s joints, Argyll Robertson pupils, incontinence, and impotence. Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Paresthesia typically occurs abruptly with a TIA and is limited to one arm or another isolated part of the body. It usually lasts about 10 minutes and is accompanied by paralysis or paresis. Associated findings include a decreased LOC, dizziness, unilateral vision loss, nystagmus, aphasia, dysarthria, tinnitus, facial weakness, dysphagia, and an ataxic gait.

Other Causes

Drugs. Phenytoin, chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine, vinblastine, and procarbazine), isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine, and parenteral gold therapy may produce transient paresthesia that disappears when the drug is discontinued.

Radiation therapy. Long-term radiation therapy may eventually cause peripheral nerve damage, resulting in paresthesia.

Special Considerations

Because paresthesia is commonly accompanied by patchy sensory loss, teach the patient safety measures. For example, have him test bathwater with a thermometer.

Patient Counseling

Discuss safety measures, and tell the patient which signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

Although children may experience paresthesia associated with the same causes as adults, many can’t describe this symptom. Nevertheless, hereditary polyneuropathies are usually first recognized in childhood.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sarwark, J. F. (2010). Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnea

Typically dramatic and terrifying to the patient, this sign refers to an attack of dyspnea that abruptly awakens the patient. Common findings include diaphoresis, coughing, wheezing, and chest discomfort. The attack abates after the patient sits up or stands for several minutes, but may recur every 2 to 3 hours.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is a sign of left-sided heart failure. It may result from decreased respiratory drive, impaired left ventricular function, enhanced reabsorption of interstitial fluid, or increased thoracic blood volume. All of these pathophysiologic mechanisms cause dyspnea to worsen when the patient lies down.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by exploring the patient’s complaint of dyspnea. Does he have dyspneic attacks only at night or at other times as well, such as after exertion or while sitting down? If so, what type of activity triggers the attack? Does he experience coughing, wheezing, fatigue, or weakness during an attack? Find out if he has a history of lower extremity edema or jugular vein distention. Ask if he sleeps with his head elevated and, if so, on how many pillows or if he sleeps in a reclining chair. Obtain a cardiopulmonary history. Does the patient or a family member have a history of a myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, or hypertension or of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma? Has the patient had cardiac surgery?

Next, perform a physical examination. Begin by taking the patient’s vital signs and forming an overall impression of his appearance. Is he noticeably cyanotic or edematous? Auscultate the lungs for crackles and wheezing and the heart for gallops and arrhythmias.

Medical Causes

Left-sided heart failure. Dyspnea — on exertion, during sleep, and eventually even at rest — is an early sign of left-sided heart failure. This sign is characteristically accompanied by CheyneStokes respirations, diaphoresis, weakness, wheezing, and a persistent, nonproductive cough or a cough that produces clear or blood-tinged sputum. As the patient’s condition worsens, he develops tachycardia, tachypnea, alternating pulse (commonly initiated by a premature beat), a ventricular gallop, crackles, and peripheral edema.

With advanced left-sided heart failure, the patient may also exhibit severe orthopnea, cyanosis, clubbing, hemoptysis, and cardiac arrhythmias as well as signs and symptoms of shock, such as

hypotension, a weak pulse, and cold, clammy skin.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as a chest X-ray, echocardiography, exercise electrocardiography, and cardiac blood pool imaging. If the hospitalized patient experiences paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, assist him to a sitting position or help him walk around the room. If necessary, provide supplemental oxygen. Try to calm him because anxiety can exacerbate dyspnea.

Patient Counseling

Explain signs and symptoms that require immediate medical attention, and discuss dietary and fluid restrictions. Explore positions that can ease breathing, and teach about prescribed medications.

Pediatric Pointers

In a child, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea usually stems from a congenital heart defect that precipitates heart failure. Help relieve the child’s dyspnea by elevating his head and calming him.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

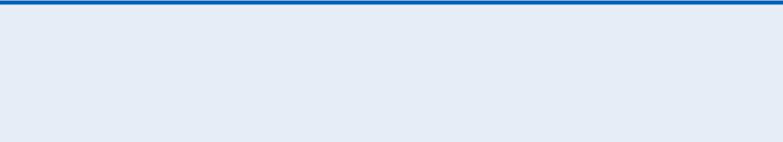

Peau d’orange

Usually a late sign of breast cancer, peau d’orange (orange peel skin) is the edematous thickening and pitting of breast skin. This slowly developing sign can also occur with breast or axillary lymph node infection, erysipelas, or Graves’ disease. Its striking orange peel appearance stems from lymphatic edema around deepened hair follicles. (See Recognizing peau d’orange, page 562.)

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when she first detected peau d’orange. Has she noticed lumps, pain, or other breast changes? Does she have related signs and symptoms, such as malaise, achiness, and weight loss? Is she lactating, or has she recently weaned her infant? Has she had previous axillary surgery that might have impaired lymphatic drainage of a breast?

Recognizing Peau D’orange

In peau d’orange, the skin appears to be pitted (as shown below). This condition usually indicates late-stage breast cancer.