Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

whereas a weak pulse may indicate low cardiac output.

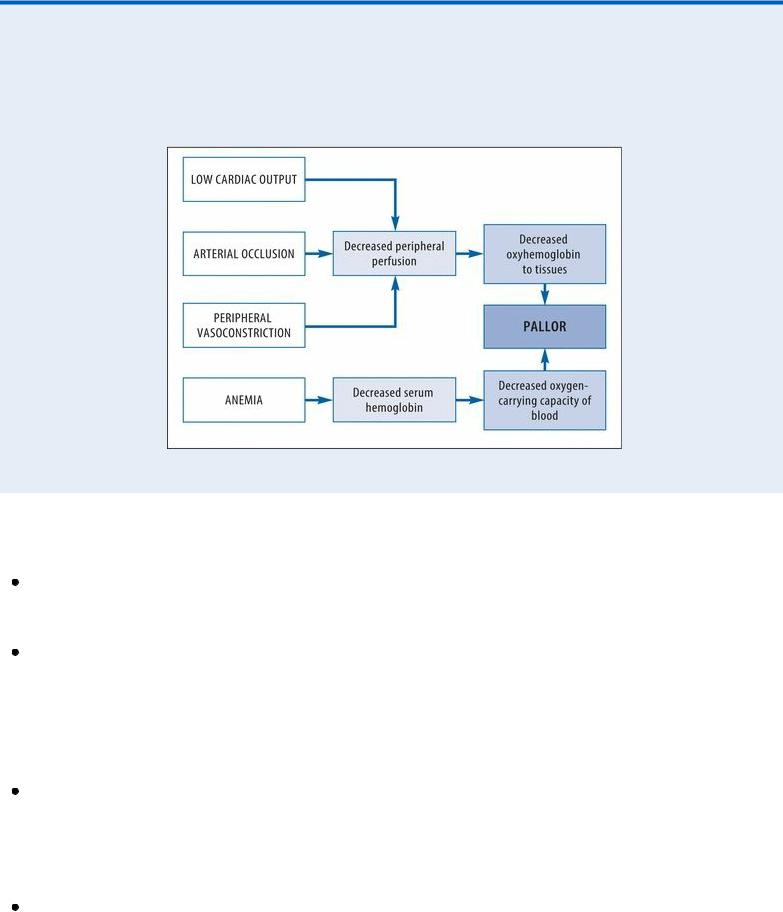

How Pallor Develops

Pallor may result from decreased peripheral oxyhemoglobin or decreased total oxyhemoglobin. The chart below illustrates the progression to pallor.

Medical Causes

Anemia. Typically, pallor develops gradually with anemia. The patient’s skin may also appear sallow or grayish. Other effects include fatigue, dyspnea, tachycardia, a bounding pulse, an atrial gallop, a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries and, possibly, crackles and bleeding tendencies. Arterial occlusion (acute). Pallor develops abruptly in the extremity with arterial occlusion, which usually results from an embolus. A line of demarcation develops, separating the cool, pale, cyanotic, and mottled skin below the occlusion from the normal skin above it. Accompanying pallor may be severe pain, intense intermittent claudication, paresthesia, and paresis in the affected extremity. Absent pulses and an increased capillary refill time below the occlusion are also characteristic.

Arterial occlusive disease (chronic). With arterial occlusive disease, pallor is specific to an extremity — usually one leg, but occasionally, both legs or an arm. It develops gradually from obstructive arteriosclerosis or a thrombus and is aggravated by elevating the extremity. Associated findings include intermittent claudication, weakness, cool skin, diminished pulses in the extremity and, possibly, ulceration and gangrene.

Frostbite. Pallor is localized to the frostbitten area, such as the feet, hands, or ears. Typically, the area feels cold, waxy and, perhaps, hard in deep frostbite. The skin doesn’t blanch, and sensation may be absent. As the area thaws, the skin turns purplish blue. Blistering and gangrene may then follow if the frostbite is severe.

Orthostatic hypotension. With orthostatic hypotension, pallor occurs abruptly on rising from a recumbent position to a sitting or standing position. A precipitous drop in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate, and dizziness are also characteristic. At times, the patient loses consciousness for several minutes.

Raynaud’s disease. Pallor of the fingers upon exposure to cold or stress is a hallmark of Raynaud’s disease. Typically, the fingers abruptly turn pale and then cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. With chronic disease, ulceration may occur.

Shock. Two forms of shock initially cause an acute onset of pallor and cool, clammy skin. With hypovolemic shock, other early signs and symptoms include restlessness, thirst, slight tachycardia, and tachypnea. As shock progresses, the skin becomes increasingly clammy, the pulse becomes more rapid and thready, and hypotension develops with narrowing pulse pressure. Other signs and symptoms include oliguria, a subnormal body temperature, and a decreased LOC. With cardiogenic shock, the signs and symptoms are similar but usually more profound.

Special Considerations

If the patient has chronic generalized pallor, prepare him for blood studies and, possibly, bone marrow biopsy. If the patient has localized pallor, he may require arteriography or other diagnostic studies to accurately determine the cause.

When pallor results from low cardiac output, administer blood and fluids as well as a diuretic, a cardiotonic, and an antiarrhythmic as needed. Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, electrocardiogram results, and hemodynamic status.

Patient Counseling

For anemia, explain the importance of an iron-rich diet and rest. For frostbite and Raynaud’s disease, discuss cold protection measures. For orthostatic hypotension, explain the need to rise slowly. Discuss signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, pallor stems from the same causes as it does in adults. It can also stem from a congenital heart defect or chronic lung disease.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Palpitations

Defined as a conscious awareness of one’s heartbeat, palpitations are usually felt over the

precordium or in the throat or neck. The patient may describe them as pounding, jumping, turning, fluttering, or flopping or as missing or skipping beats. Palpitations may be regular or irregular, fast or slow, and paroxysmal or sustained.

Although usually insignificant, palpitations may result from a cardiac or metabolic disorder and from the effects of certain drugs. Nonpathologic palpitations may occur with a newly implanted prosthetic valve because the valve’s clicking sound heightens the patient’s awareness of his heartbeat. Transient palpitations may accompany emotional stress (such as fright, anger, or anxiety) or physical stress (such as exercise and fever). They can also accompany the use of stimulants, such as tobacco and caffeine.

To help characterize the palpitations, ask the patient to simulate their rhythm by tapping his finger on a hard surface. An irregular “skipped beat” rhythm points to premature ventricular contractions, whereas an episodic racing rhythm that ends abruptly suggests paroxysmal atrial tachycardia.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient complains of palpitations, ask him about dizziness and shortness of breath. Then, inspect for pale, cool, clammy skin. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and an irregular or abnormal pulse. If these signs are present, suspect cardiac arrhythmia. Prepare to begin cardiac monitoring and, if necessary, to deliver electroshock therapy. Start oxygen therapy via a mask or nasal cannula. Begin an I.V. line to administer an antiarrhythmic, if needed.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, perform a complete cardiac history and physical examination. Ask if he has a cardiovascular or pulmonary disorder, which may produce arrhythmias. Does the patient have a history of hypertension or hypoglycemia? Make sure to obtain a drug history. Has the patient recently started cardiac glycoside therapy? Also, ask about caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol consumption.

Then, explore associated symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, and angina. Finally, auscultate for gallops, murmurs, and abnormal breath sounds.

Medical Causes

Anxiety attack (acute). Anxiety is the most common cause of palpitations in children and adults. With this disorder, palpitations may be accompanied by diaphoresis, facial flushing, trembling, and an impending sense of doom. Almost invariably, patients hyperventilate, which may lead to dizziness, weakness, and syncope. Other typical findings include tachycardia, precordial pain, shortness of breath, stomach ache, diarrhea, restlessness, and insomnia.

Cardiac arrhythmias. Paroxysmal or sustained palpitations may be accompanied by dizziness, weakness, and fatigue. The patient may also experience an irregular, rapid, or slow pulse rate; decreased blood pressure; confusion; pallor; oliguria; and diaphoresis.

Hypertension. With hypertension, the patient may be asymptomatic or may complain of sustained palpitations alone or with a headache, dizziness, tinnitus, and fatigue. His blood pressure typically exceeds 140/90 mm Hg. He may also experience nausea and vomiting, seizures, and a decreased level of consciousness.

Hypocalcemia. Typically, hypocalcemia produces palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. It progresses from paresthesia to muscle tension and carpopedal spasms. The patient may also exhibit muscle twitching, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, chorea, and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs.

Mitral prolapse. Mitral prolapse is a valvular disorder that may cause paroxysmal palpitations accompanied by sharp, stabbing, or aching precordial pain. The hallmark of this disorder, however, is a midsystolic click followed by an apical systolic murmur. Associated signs and symptoms may include dyspnea, dizziness, severe fatigue, a migraine headache, anxiety, paroxysmal tachycardia, chest pain, crackles, and peripheral edema.

Mitral stenosis. Early features of mitral stenosis typically include sustained palpitations accompanied by exertional dyspnea and fatigue. Auscultation also reveals a loud S1 or opening snap and a rumbling diastolic murmur at the apex. Patients may also experience related signs and symptoms, such as an atrial gallop and, with advanced mitral stenosis, orthopnea, dyspnea at rest, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, ascites, hepatomegaly, and atrial fibrillation.

Thyrotoxicosis. A characteristic symptom of thyrotoxicosis, sustained palpitations may be accompanied by tachycardia, dyspnea, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance and, possibly, exophthalmos and an enlarged thyroid. The patient may also experience an atrial or a ventricular gallop.

Other Causes

Drugs. Palpitations may result from drugs that precipitate cardiac arrhythmias or increase cardiac output, such as cardiac glycosides; sympathomimetics, such as cocaine; ganglionic blockers; beta-adrenergic blockers; calcium channel blockers; atropine; and minoxidil.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies, such as ginseng, may cause adverse reactions, including palpitations and an irregular heartbeat.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as an electrocardiogram and Holter’s monitoring. Remember that even mild palpitations can cause the patient much concern. Maintain a quiet, comfortable environment to minimize anxiety and perhaps decrease palpitations.

Patient Counseling

Explain diagnostic tests the patient needs, and teach him ways to reduce anxiety.

Pediatric Pointers

Palpitations in children commonly result from a fever and congenital heart defects, such as patent ductus arteriosus and septal defects. Because many children can’t describe this complaint, focus your

attention on objective measurements, such as cardiac monitoring, physical examination, and laboratory tests.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics. Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St.

Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis. Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Papular Rash

A papular rash consists of small, raised, circumscribed — and perhaps discolored (red to purple) — lesions known as papules. It may erupt anywhere on the body in various configurations and may be acute or chronic. Papular rashes characterize many cutaneous disorders; they may also result from allergy and from infectious, neoplastic, and systemic disorders. (To compare papules with other skin lesions, see Recognizing Common Skin Lesions.)

History and Physical Examination

Your first step is to fully evaluate the papular rash: note its color, configuration, and location on the patient’s body. Find out when it erupted. Has the patient noticed changes in the rash since then? Is it itchy or burning, or painful or tender? Has there ever been discharge or drainage from the rash? If so, have the patient describe it. Also, have him describe associated signs and symptoms, such as fevers, headaches, and GI distress.

Next, obtain a medical history, including allergies; previous rashes or skin disorders; infections; childhood diseases; sexual history, including sexually transmitted diseases; and cancers. Has the patient recently been bitten by an insect or rodent or been exposed to anyone with an infectious disease? Finally, obtain a complete drug history.

Medical Causes

Acne vulgaris. With acne vulgaris, rupture of enlarged comedones produces inflamed — and perhaps, painful and pruritic — papules, pustules, nodules, or cysts on the face and sometimes the shoulders, chest, and back.

Anthrax (cutaneous). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Cutaneous anthrax occurs when the bacterium enters a cut or abrasion on the skin. The infection begins as a small, painless, or pruritic macular or papular lesion resembling an insect bite. Within 1 to 2 days, it develops into a vesicle and then a painless ulcer with a characteristic black, necrotic center. Lymphadenopathy, malaise, a headache, or a fever may develop.

Dermatomyositis. Gottron’s papules — flat, violet-colored lesions on the dorsa of the finger

joints and the nape of the neck and shoulders — are pathognomonic of dermatomyositis, as is the dusky lilac discoloration of periorbital tissue and lid margins (heliotrope edema). These signs may be accompanied by a transient, erythematous, macular rash in a malar distribution on the face and sometimes on the scalp, forehead, neck, upper torso, and arms. This rash may be preceded by symmetrical muscle soreness and weakness in the pelvis, upper extremities, shoulders, neck and, possibly, the face (polymyositis).

Follicular mucinosis. With follicular mucinosis, perifollicular papules or plaques are accompanied by prominent alopecia.

Fox-Fordyce disease. Fox-Fordyce disease is a chronic disorder that’s marked by pruritic papules on the axillae, pubic area, and areolae associated with apocrine sweat gland inflammation. Sparse hair growth in these areas is also common.

Granuloma annulare. Granuloma annulare is a benign, chronic disorder that produces papules that usually coalesce to form plaques. The papules spread peripherally to form a ring with a normal or slightly depressed center. They usually appear on the feet, legs, hands, or fingers and may be pruritic or asymptomatic.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Acute infection with the HIV retrovirus typically causes a generalized maculopapular rash. Other signs and symptoms include a fever, malaise, a sore throat, and a headache. Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. Most patients don’t recall these symptoms of acute infection.

Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s sarcoma is characterized by purple or blue papules or macules of vascular origin on the skin, mucous membranes, and viscera. These lesions decrease in size with firm pressure and then return to their original size within 10 to 15 seconds. They may become scaly and ulcerate with bleeding.

Multiple variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma are known; most individuals are immunocompromised in some way, especially those with HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Human herpes virus 8 has been strongly implicated as a cofactor in the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Kawasaki disease. Patients with Kawasaki disease have a distinct erythematous maculopapular rash, usually on the trunk and the extremities. Accompanying symptoms include high fever, irritability, red eyes, bright red cracked lips, a strawberry tongue, swollen hands and feet, peeling skin on the fingertips and toes, and cervical lymphadenopathy. More severe complications include coronary artery abnormalities.

Lichen planus. Discrete, flat, angular or polygonal, violet papules, commonly marked with white lines or spots, are characteristic of lichen planus. The papules may be linear or coalesce into plaques and usually appear on the lumbar region, genitalia, ankles, anterior tibiae, and wrists. Lesions usually develop first on the buccal mucosa as a lacy network of white or gray threadlike papules or plaques. Pruritus, distorted fingernails, and atrophic alopecia commonly occur.

Mononucleosis (infectious). A maculopapular rash that resembles rubella is an early sign of mononucleosis in 10% of patients. The rash is typically preceded by a headache, malaise, and fatigue. It may be accompanied by a sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, and fluctuating temperature with an evening peak of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C). Splenomegaly and hepatic inflammation may also develop.

Necrotizing vasculitis. With necrotizing vasculitis, crops of purpuric, but otherwise asymptomatic, papules are typical. Some patients also develop a low-grade fever, a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and abdominal pain.

Pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea begins with an erythematous “herald patch” — a slightly raised, oval lesion about 2 to 6 cm in diameter that may appear anywhere on the body. A few days to weeks later, yellow to tan or erythematous patches with scaly edges appear on the trunk, arms, and legs, commonly erupting along body cleavage lines in a characteristic “pine tree” pattern. These patches may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic, are 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter, and typically improve with skin exposure.

Polymorphic light eruption. Abnormal reactions to light may produce papular, vesicular, or nodular rashes on sun-exposed areas. Other symptoms include pruritus, a headache, and malaise. Psoriasis. Psoriasis is a common chronic disorder that begins with small, erythematous papules on the scalp, chest, elbows, knees, back, buttocks, and genitalia. These papules are sometimes pruritic and painful. Eventually, they enlarge and coalesce, forming elevated, red, scaly plaques covered by characteristic silver scales, except in moist areas such as the genitalia. These scales may flake off easily or thicken, covering the plaque. Associated features include pitted fingernails and arthralgia.

Rosacea. Rosacea is a hyperemic disorder characterized by persistent erythema, telangiectasia, and recurrent eruption of papules and pustules on the forehead, malar areas, nose, and chin. Eventually, eruptions occur more frequently and erythema deepens. Rhinophyma may occur in severe cases.

Seborrheic keratosis. With seborrheic keratosis, a cutaneous disorder, benign skin tumors begin as small, yellow-brown papules on the chest, back, or abdomen, eventually enlarging and becoming deeply pigmented. However, in blacks, these papules may remain small and affect only the malar part of the face (dermatosis papulosa nigra).

Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include a high fever, malaise, prostration, a severe headache, a backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust, and later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

Syringoma. With syringoma, adenoma of the sweat glands produces a yellowish or erythematous papular rash on the face (especially the eyelids), neck, and upper chest.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is characterized by a “butterfly rash” of erythematous maculopapules or discoid plaques that appear in a malar distribution across the nose and cheeks. Similar rashes may appear elsewhere, especially on exposed body areas. Other cardinal features include photosensitivity and nondeforming arthritis, especially in the hands, feet, and large joints. Common effects are patchy alopecia, mucous membrane ulceration, a lowgrade or spiking fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, dyspnea, tachycardia, hematuria, a headache, and irritability.

Typhus. Typhus is a rickettsial disease transmitted to humans by fleas, mites, or body lice. Initial symptoms include a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise, followed by an abrupt onset of chills, a fever, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

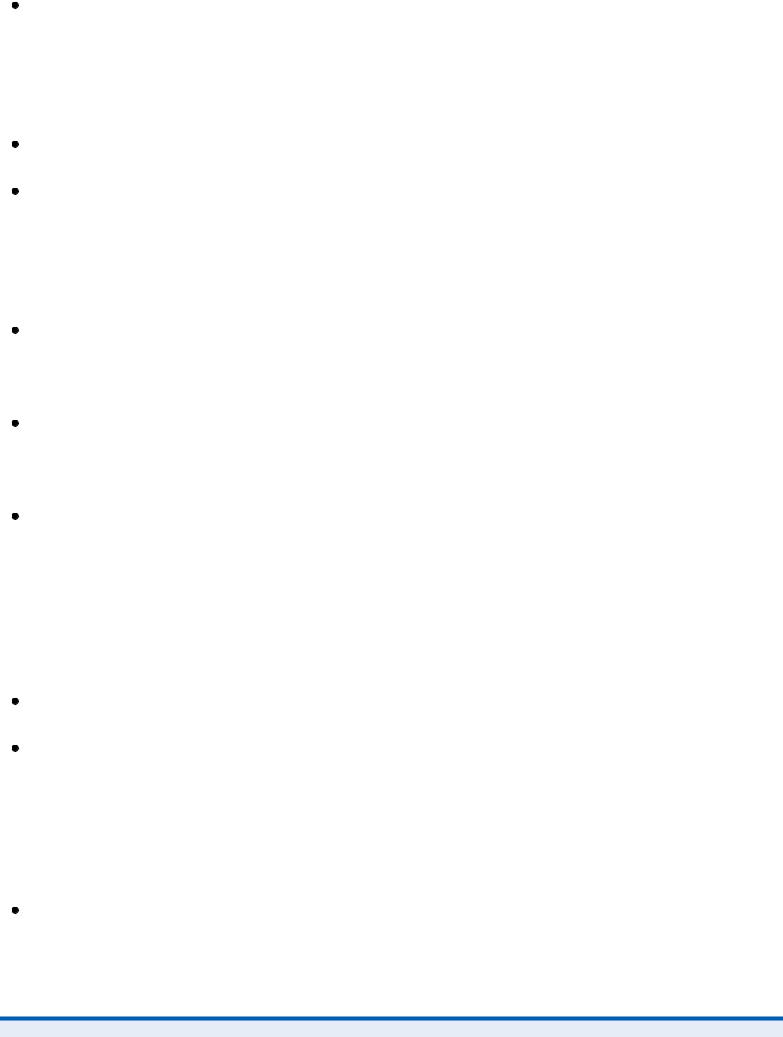

Recognizing Common Skin Lesions

MACULE

A small (usually less than 1 cm in diameter), flat blemish or discoloration that can be brown, tan, red, or white and has same texture as surrounding skin.

BULLA

A raised, thin-walled blister greater than 0.5 cm in diameter, containing clear or serous fluid.

VESICLE

A small (less than 0.5 cm in diameter), thin-walled, raised blister containing clear, serous, purulent, or bloody fluid.

PUSTULE

A circumscribed, pusor lymph-filled, elevated lesion that varies in diameter and may be firm or soft and white or yellow.

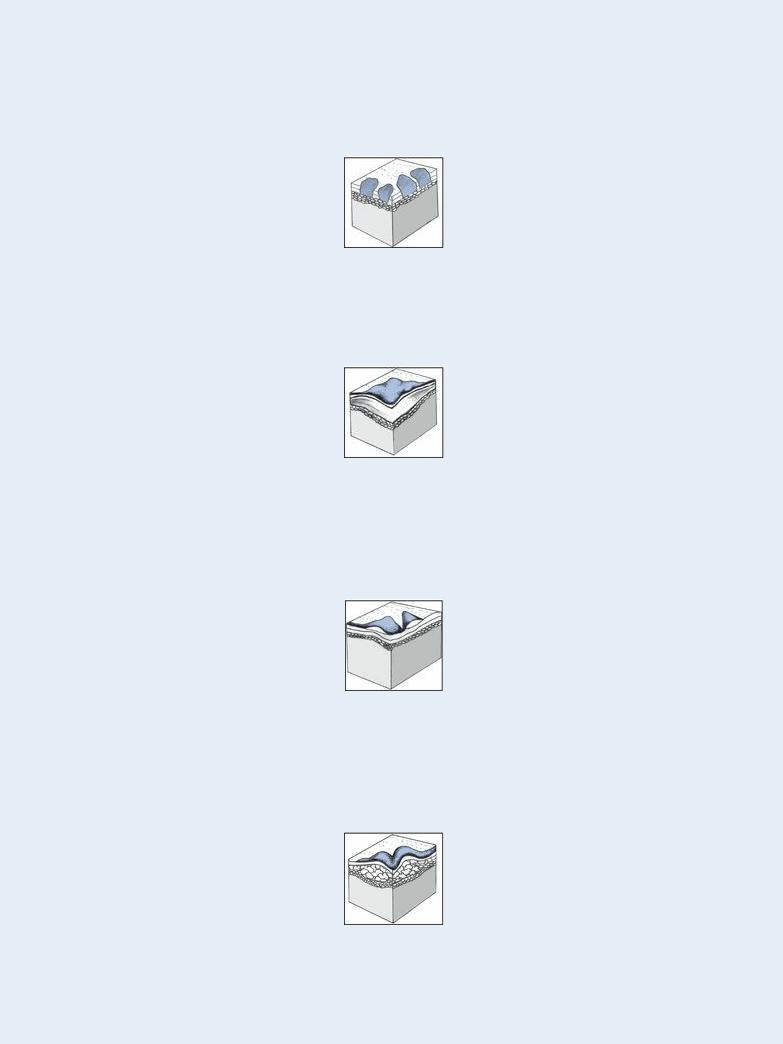

WHEAL

A slightly raised, firm lesion of variable size and shape, surrounded by edema; skin may be red or pale.

NODULE

A small, firm, circumscribed, elevated lesion 1 to 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration.

PAPULE

A small, solid, raised lesion less than 1 cm in diameter, with red to purple skin discoloration.

TUMOR

A solid, raised mass usually larger than 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration.

Other Causes

Drugs. Transient maculopapular rashes, usually on the trunk, may accompany reactions to many drugs, including antibiotics, such as tetracycline, ampicillin, cephalosporins, and sulfonamides; benzodiazepines, such as diazepam; lithium; phenylbutazone; gold salts; allopurinol; isoniazid; and salicylates.

Special Considerations

Apply cool compresses or an antipruritic lotion. Administer an antihistamine for allergic reactions and an antibiotic for infection.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient appropriate skin care measures, and explain ways to reduce itching.

Pediatric Pointers

Common causes of papular rashes in children are infectious diseases, such as molluscum contagiosum and scarlet fever; scabies; insect bites; allergies and drug reactions; and miliaria, which occurs in three forms, depending on the depth of sweat gland involvement.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients who are bedridden, the first sign of pressure ulcers is commonly an erythematous area, sometimes with firm papules. If not properly managed, these lesions progress to deep ulcers and can lead to death.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P. , & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008) . Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447) . St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L. , & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Paralysis

Paralysis, the total loss of voluntary motor function, results from severe cortical or pyramidal tract damage. It can occur with a cerebrovascular disorder, degenerative neuromuscular disease, trauma, tumor, or central nervous system infection. Acute paralysis may be an early indicator of a lifethreatening disorder such as Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Paralysis can be local or widespread, symmetrical or asymmetrical, transient or permanent, and spastic or flaccid. It’s commonly classified according to location and severity as paraplegia (sometimes, transient paralysis of the legs), quadriplegia (permanent paralysis of the arms, legs, and body below the level of the spinal lesion), or hemiplegia (unilateral paralysis of varying severity and permanence). Incomplete paralysis with profound weakness (paresis) may precede total paralysis in some patients.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If paralysis has developed suddenly, suspect trauma or an acute vascular insult. After ensuring that the patient’s spine is properly immobilized, quickly determine his level of consciousness (LOC) and take his vital signs. Elevated systolic blood pressure, widening