Borchers Andrea Ann (ed.) Handbook of Signs & Symptoms 2015

.pdf

ventilation, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be necessary. Evaluate the degree of jaundice and abdominal distention, and palpate the liver to assess the degree of enlargement.

Obtain a complete medical history, relying on information from the patient’s family if necessary. Focus on factors that may have precipitated hepatic disease or coma, such as a recent severe infection; overuse of sedatives, analgesics (especially acetaminophen), alcohol, or diuretics; excessive protein intake; or recent blood transfusion, surgery, or GI bleeding.

Medical Causes

Hepatic encephalopathy. Fetor hepaticus usually occurs in the final, comatose stage of this disorder but may occur earlier. Tremors progress to asterixis in the impending stage; lethargy, aberrant behavior, and apraxia also occur. Hyperventilation and stupor mark the stuporous stage, during which the patient acts agitated when aroused. Seizures and coma herald the final stage, along with decreased pulse and respiratory rates, a positive Babinski’s sign, hyperactive reflexes, decerebrate posture, and opisthotonos.

Special Considerations

Effective treatment of hepatic encephalopathy reduces blood ammonia levels by eliminating ammonia from the GI tract. You may have to administer neomycin or lactulose to suppress bacterial production of ammonia, give sorbitol solution to induce osmotic diarrhea, give potassium supplements to correct alkalosis, provide continuous gastric aspiration of blood, or maintain the patient on a low-protein diet. If these methods prove unsuccessful, hemodialysis or plasma exchange transfusions may be performed.

During treatment, closely monitor the patient’s LOC, intake and output, and fluid and electrolyte balance.

Patient Counseling

Advise the patient to restrict his intake of protein, as necessary. Teach him about current treatments and signs and symptoms that should be reported.

Pediatric Pointers

A child who’s slipping into a hepatic coma may cry, be disobedient, or become preoccupied with an activity.

Geriatric Pointers

Along with fetor hepaticus, elderly patients with hepatic encephalopathy may exhibit disturbances of awareness and mentation, such as forgetfulness and confusion.

REFERENCES

Devictor, D. , Tissieres, P . , Afanetti, M., & Debray, D. (2011) . Acute liver failure in children. Clinical Research Hepatology and Gastroenterology, 35, 430–437.

Shanmugam, N. P. , Bansal, S., Greenough, A., Verma, A ., & Dhawan, A. (2011). Neonatal liver failure: Aetiologies and management.

European Journal of Pediatrics, 170, 573–581.

Fever

[Pyrexia]

A fever is a common sign that can arise from many disorders. Because these disorders can affect virtually any body system, a fever in the absence of other signs usually has little diagnostic significance. A persistent high fever, though, represents an emergency.

A fever can be classified as low (oral reading of 99°F to 100.4°F [37.2°C to 38°C]), moderate (100.5°F to 104°F [38°C to 40°C]), or high (above 104°F). A fever greater than 106°F (41.1°C) causes unconsciousness and, if sustained, leads to permanent brain damage.

A fever may also be classified as remittent, intermittent, sustained, relapsing, or undulant. Remittent fever, the most common type, is characterized by daily temperature fluctuations above the normal range. Intermittent fever is marked by a daily temperature drop into the normal range and then a rise back to above normal. An intermittent fever that fluctuates widely, typically producing chills and sweating, is called hectic, or septic, fever. Sustained fever involves persistent temperature elevation with little fluctuation. Relapsing fever consists of alternating feverish and afebrile periods. Undulant fever refers to a gradual increase in temperature that stays high for a few days and then decreases gradually.

Further classification involves duration — either brief (less than 3 weeks) or prolonged. Prolonged fevers include fever of unknown origin, a classification used when careful examination fails to detect an underlying cause.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect a fever higher than 106°F, take the patient’s other vital signs and determine his level of consciousness (LOC). Administer an antipyretic and begin rapid cooling measures: Apply ice packs to the axillae and groin, give tepid sponge baths, or apply a cooling blanket. These methods may evoke a cooling response; to prevent this, constantly monitor the patient’s rectal temperature.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s fever is only mild to moderate, ask him when it began and how high his temperature reached. Did the fever disappear, only to reappear later? Did he experience other symptoms, such as chills, fatigue, or pain?

Obtain a complete medical history, noting especially immunosuppressive treatments or disorders, infection, trauma, surgery, diagnostic testing, and the use of anesthesia or other medications. Ask about recent travel because certain diseases are endemic.

Let the history findings direct your physical examination. Because a fever can accompany diverse disorders, the examination may range from a brief evaluation of one body system to a comprehensive review of all systems. (See How Fever Develops, page 320.)

Medical Causes

Anthrax, cutaneous. The patient may experience a fever along with lymphadenopathy, malaise, and a headache. After the bacterium Bacillus anthracis enters a cut or abrasion on the skin, the infection begins as a small, painless, or pruritic macular or papular lesion resembling an insect bite. Within 1 to 2 days, the lesion develops into a vesicle and then into a painless ulcer with a characteristic black, necrotic center.

Anthrax, GI. Following the ingestion of contaminated meat from an animal infected with the bacterium B. anthracis, the patient experiences a fever, a loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting. The patient may also experience abdominal pain, severe bloody diarrhea, and hematemesis.

Anthrax, inhalation. The initial signs and symptoms of inhalation anthrax are flulike, including a fever, chills, weakness, a cough, and chest pain. The disease generally occurs in two stages, with a period of recovery after the initial symptoms. The second stage develops abruptly with rapid deterioration marked by a fever, dyspnea, stridor, and hypotension, generally leading to death within 24 hours.

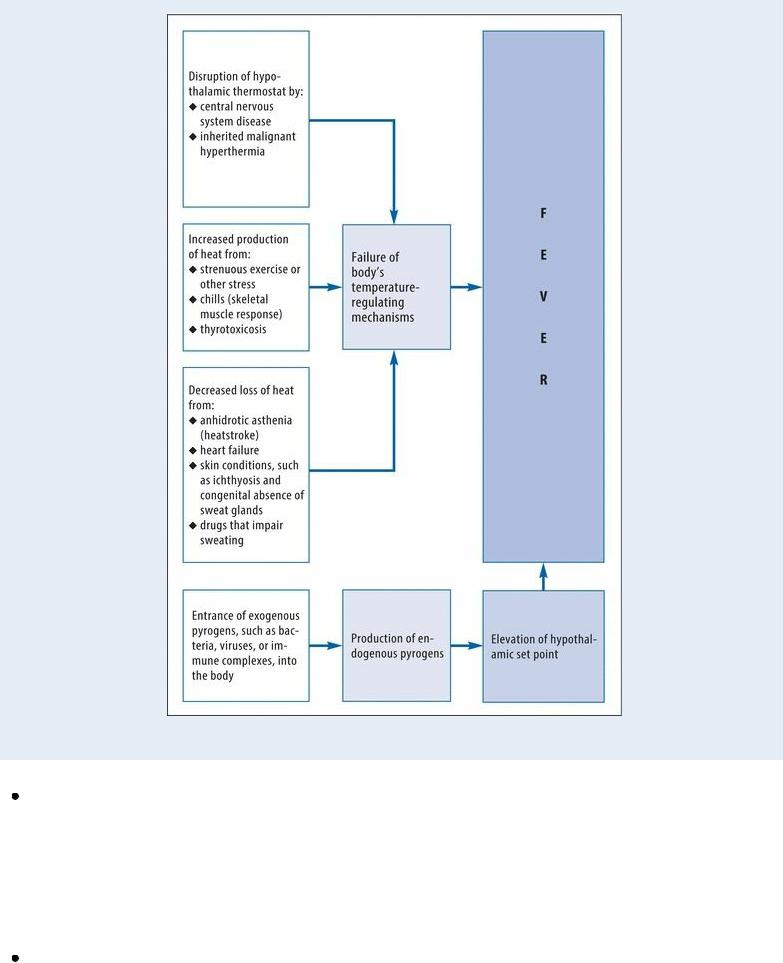

How Fever Develops

Body temperature is regulated by the hypothalamic thermostat, which has a specific set point under normal conditions. A fever can result from a resetting of this set point or from an abnormality in the thermoregulatory system itself, as shown in this flowchart.

Avian flu. Fever is a common symptom of infection with the avian influenza A virus (H5N1, the most virulent strain). Avian flu, also called bird flu, was first detected in humans in 1996. Symptoms can range from conventional human flulike symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, runny nose, headache, and conjunctivitis, to more severe infections, viral pneumonia, and acute respiratory distress. Patients should be aware of the risk of cross-contamination from raw poultry juices during food preparation and about the need to wash all surfaces that come in contact with raw poultry.

Escherichia coli O157:H7. A fever, bloody diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal cramps occur after eating undercooked beef or other foods contaminated with this strain of bacteria. In children younger than age 5 and in elderly patients, hemolytic-uremic syndrome may develop (in which the red blood cells are destroyed), and this may ultimately lead to acute renal failure.

Immune complex dysfunction. When present, a fever usually remains low, although moderate elevations may accompany erythema multiforme. Fever may be remittent or intermittent, as in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or systemic lupus erythematosus, or sustained, as in polyarteritis. As one of several vague, prodromal complaints (such as fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss), a fever produces nocturnal diaphoresis and accompanies such associated signs and symptoms as diarrhea and a persistent cough (with AIDS) or morning stiffness (with rheumatoid arthritis). Other disease-specific findings include a headache and vision loss (temporal arteritis); pain and stiffness in the neck, shoulders, back, or pelvis (ankylosing spondylitis and polymyalgia rheumatica); skin and mucous membrane lesions (erythema multiforme); and urethritis with urethral discharge and conjunctivitis (Reiter’s syndrome).

Infectious and inflammatory disorders. A fever ranges from low (in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) to extremely high (in those with bacterial pneumonia, necrotizing fasciitis, or Ebola or Hantavirus). It may be remittent, as in those with infectious mononucleosis or otitis media; hectic (recurring daily with sweating, chills, and flushing), as in those with lung abscess, influenza, or endocarditis; sustained, as in those with meningitis; or relapsing, as in those with malaria. A fever may arise abruptly, as in those with toxic shock syndrome or Rocky Mountain spotted fever, or insidiously, as in those with mycoplasmal pneumonia. In patients with hepatitis, a fever may represent a disease prodrome; in those with appendicitis, it follows the acute stage. Its sudden late appearance with tachycardia, tachypnea, and confusion heralds life-threatening septic shock in patients with peritonitis or gram-negative bacteremia.

Associated signs and symptoms involve every system. The cyclic variations of hectic fever typically produce alternating chills and diaphoresis. General systemic complaints include weakness, anorexia, and malaise.

Kawasaki disease or syndrome. Kawasaki disease, usually seen in children younger than age 5 and with more prevalence in boys, characteristically presents with a high, spiking fever (ranging from 102°F to 104°F [39°C to 40°C]) that typically lasts 5 days or more (or until I.V. gamma globulin is given before the fifth day). Other symptoms include irritability, nondraining conjunctivitis (red eyes), bright red cracked lips, a strawberry tongue, swollen hands and feet, peeling skin on the fingertips and toes, rash on the trunk and genitals, and cervical lymphadenopathy.

Listeriosis. Signs and symptoms of listeriosis include a fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. If the infection spreads to the nervous system, meningitis may develop; symptoms include a fever, a headache, nuchal rigidity, and a change in the LOC.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Infections during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Monkey pox. Fever greater than 99.3°F (37.4°C) is commonly symptomatic of monkey pox. Other findings may include conjunctivitis, cough, shortness of breath, headache, muscle aches, backache, general feeling of discomfort and exhaustion, and rash.

Neoplasms. Primary neoplasms and metastases can produce a prolonged fever of varying elevations. For instance, acute leukemia may present insidiously with a low-grade fever, pallor,

and bleeding tendencies or more abruptly with a high fever, frank bleeding, and prostration. Occasionally, Hodgkin’s disease produces an undulant fever or Pel-Ebstein fever, an irregularly relapsing fever.

In addition to a fever and nocturnal diaphoresis, neoplastic disease typically causes anorexia, fatigue, malaise, and weight loss. Examination may reveal lesions, lymphadenopathy, palpable masses, and hepatosplenomegaly.

Plague (Yersinia pestis). The bubonic form of plague (transmitted to man when bitten by infected fleas) causes a fever, chills, and swollen, inflamed, and tender lymph nodes near the bite site. The septicemic form develops as a fulminant illness generally with the bubonic form. The pneumonic form manifests as a sudden onset of chills, a fever, a headache, and myalgia after person-to-person transmission via the respiratory tract. Other signs and symptoms of the pneumonic form include a productive cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, hemoptysis, increasing respiratory distress, and cardiopulmonary insufficiency.

Q fever. Q fever is a rickettsial disease that’s caused by the infection of Coxiella burnetii. It causes a fever, chills, a severe headache, malaise, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. The fever may last up to 2 weeks. In severe cases, the patient may develop hepatitis or pneumonia.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Fever is an initial symptom of infection with RSV, a virus that causes infections of the upper and lower respiratory tract in most children by age 2. Most healthy children and adults infected with RSV have an unremarkable course and recover within 8 to 15 days. Most patients typically present with symptoms resembling a mild cold, including congestion, runny nose, cough, low-grade fever, and a sore throat. However, some patients with underlying respiratory problems, especially premature infants, may develop a more severe RSV infection that requires hospitalization. They may exhibit such signs as high fever, severe cough, wheezing, rapid breathing, high-pitched expiratory wheezes, lethargy, poor eating, irritability, difficulty breathing, and hypoxia.

Rhabdomyolysis. Rhabdomyolysis results in muscle breakdown and release of the muscle cell contents (myoglobin) into the bloodstream, with signs and symptoms that include a fever, muscle weakness or pain, nausea, vomiting, malaise, or dark urine. Acute renal failure is the most commonly reported complication of the disorder. It results from renal structure obstruction and injury during the kidney’s attempt to filter the myoglobin from the bloodstream.

Rift Valley fever. Typical signs and symptoms of Rift Valley fever include a fever, myalgia, weakness, dizziness, and back pain. A small percentage of patients may develop encephalitis or may progress to hemorrhagic fever that can lead to shock and hemorrhage. Inflammation of the retina may result in some permanent vision loss.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). SARS is an acute infectious disease of unknown etiology; however, a novel coronavirus has been implicated as a possible cause. Although most cases have been reported in Asia (China, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand), cases have been documented in Europe and North America. The incubation period is 2 to 7 days, and the illness generally begins with a fever (usually greater than 100.4°F [38°C]). Other signs and symptoms include a headache, malaise, a dry nonproductive cough, and dyspnea. The severity of the illness is highly variable, ranging from mild illness to pneumonia and, in some cases, progressing to respiratory failure and death.

Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include a high fever, malaise, prostration, a severe headache, a backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash

develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust, and later the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

Thermoregulatory dysfunction. Thermoregulatory dysfunction is marked by a sudden onset of fever that rises rapidly and remains as high as 107°F (41.7°C). It occurs in such life-threatening disorders as heatstroke, thyroid storm, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and malignant hyperthermia and in lesions of the central nervous system (CNS). A low or moderate fever appears in dehydrated patients.

A prolonged high fever commonly produces vomiting, anhidrosis, a decreased LOC, and hot, flushed skin. Related cardiovascular effects may include tachycardia, tachypnea, and hypotension. Other disease-specific findings include skin changes, such as dry skin and mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, and oliguria with dehydration; mottled cyanosis with malignant hyperthermia; diarrhea with thyroid storm; and ominous signs of increased intracranial pressure (a decreased LOC with bradycardia, a widened pulse pressure, and an increased systolic pressure) with CNS tumor, trauma, or hemorrhage.

Tularemia. Tularemia, also known as rabbit fever, causes an abrupt onset of a fever, chills, a headache, generalized myalgia, a nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and empyema.

Typhus. Typhus is a rickettsial disease in which the patient initially experiences a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise. These signs and symptoms are followed by an abrupt onset of a fever, chills, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

West Nile encephalitis. West Nile encephalitis is a brain infection caused by West Nile virus

— a mosquito-borne Flavivirus that’s commonly found in Africa, West Asia, and the Middle East and rarely in North America. Mild infection is common; signs and symptoms include a fever, a headache, and body aches, usually with skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infection is marked by a high fever, a headache, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional convulsions, paralysis and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

Diagnostic tests. Immediate or delayed fever infrequently follows radiographic tests that use contrast medium.

Drugs. A fever and rash commonly result from hypersensitivity to antifungals, sulfonamides, penicillins, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, barbiturates, phenytoin, quinidine, iodides, phenolphthalein, methyldopa, procainamide, and some antitoxins. A fever can accompany chemotherapy, especially with bleomycin, vincristine, and asparaginase. It can result from drugs that impair sweating, such as anticholinergics, phenothiazines, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. A drug-induced fever typically disappears after the involved drug is discontinued. A fever can also stem from toxic doses of salicylates, amphetamines, and tricyclic antidepressants. Inhaled anesthetics and muscle relaxants can trigger malignant hyperthermia in patients with this inherited trait.

Treatments. Remittent or intermittent low fever may occur for several days after surgery. Transfusion reactions characteristically produce an abrupt onset of a fever and chills.

Special Considerations

Regularly monitor the patient’s temperature, and record it on a chart for easy follow-up of the temperature curve. Provide increased fluid and nutritional intake. When administering a prescribed antipyretic, minimize resultant chills and diaphoresis by following a regular dosage schedule. Promote patient comfort by maintaining a stable room temperature and providing frequent changes of bedding and clothing. For high fevers, initial treatment is with a hypothermia blanket. Prepare the patient for laboratory tests, such as complete blood count and cultures of blood, urine, sputum, and wound drainage.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient about the proper way to take his oral temperature at home. Emphasize the importance of increased fluid intake (unless contraindicated). Discuss the use of antipyretics.

Pediatric Pointers

Infants and young children experience higher and more prolonged fevers, more rapid temperature increases, and greater temperature fluctuations than older children and adults.

Keep in mind that seizures commonly accompany an extremely high fever, so take appropriate precautions. Place cool washcloths over the forehead, wrists, and groin to reduce fever. Never use alcohol baths. Also, instruct parents not to give aspirin to a child with varicella or flulike symptoms because of the risk of precipitating Reye’s syndrome.

Common pediatric causes of fever include varicella, croup syndrome, dehydration, meningitis, mumps, otitis media, pertussis, roseola infantum, rubella, rubeola, and tonsillitis. A fever can also occur as a reaction to immunizations and antibiotics.

Geriatric Pointers

Elderly people may have an altered sweating mechanism that predisposes them to heatstroke when exposed to high temperatures; they may also have an impaired thermoregulatory mechanism, making temperature change a much less reliable measure of disease severity.

REFERENCES

Graham, J. G., MacDonald, L. J., Hussain, S. K., Sharma, U. M., Kurten, R. C., & Voth, D. E. (2013) . Virulent Coxiella burnetii pathotypes productively infect primary human alveolar macrophages. Cellular Microbiology, 15(6), 1012–1025.

Van der Hoek, W ., Dijkstra, F., Schimmer, B., Schneeberger, P. M. , Vellema, P., Wijkmans, C., … van Duynhoven, Y. (2010). Q fever in the Netherlands: An update on the epidemiology and control measures. European Surveillance, 15, 19520.

Flank Pain

Pain in the flank, the area extending from the ribs to the ilium, is a leading indicator of renal and upper urinary tract disease or trauma. Depending on the cause, this symptom may vary from a dull ache to severe stabbing or throbbing pain and may be unilateral or bilateral and constant or

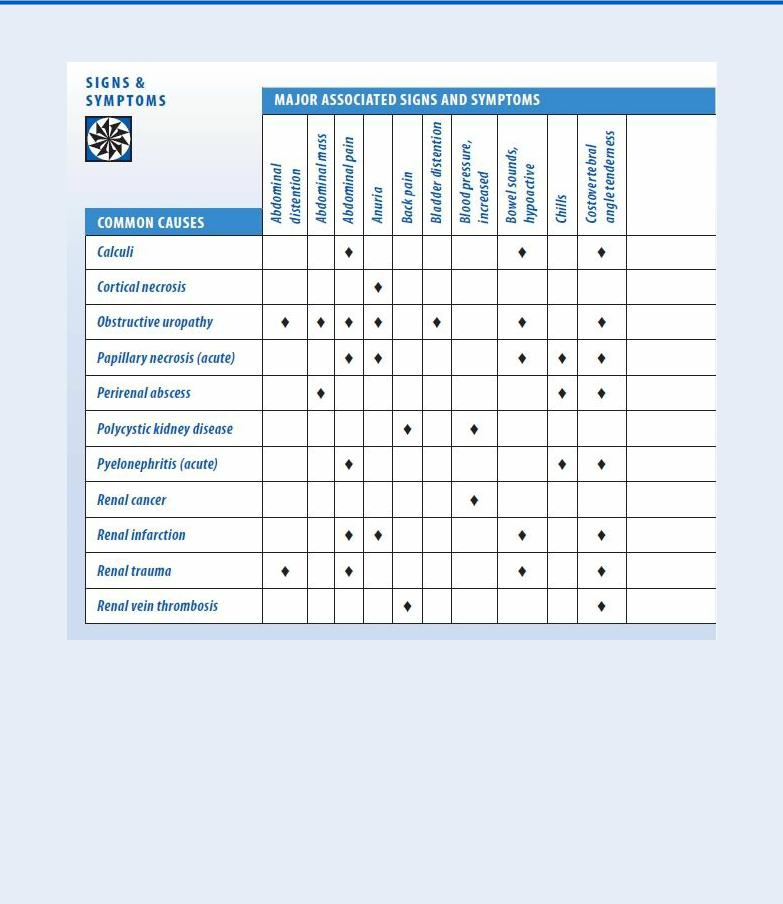

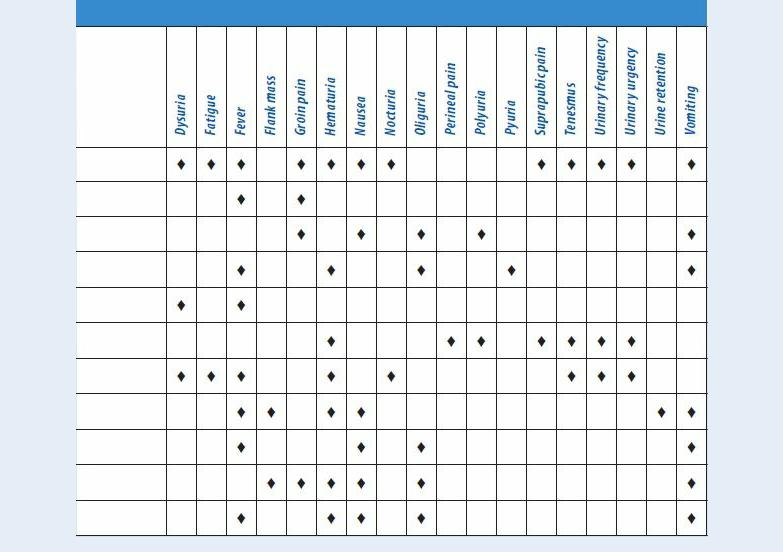

intermittent. It’s aggravated by costovertebral angle (CVA) percussion and, in patients with renal or urinary tract obstruction, by increased fluid intake and ingestion of alcohol, caffeine, or diuretics. Unaffected by position changes, flank pain typically responds only to analgesics or to treatment of the underlying disorder. (See Flank Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings, pages 326 and 327.)

Flank Pain: Common Causes and Associated Findings

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has suffered trauma, quickly look for a visible or palpable flank mass, associated injuries, CVA pain, hematuria, Turner’s sign, and signs of shock, such as tachycardia and cool, clammy skin. If one or more is present, insert an I.V. line to allow fluid or drug infusion. Insert an indwelling urinary catheter to monitor urine output and evaluate hematuria. Obtain blood samples for typing and crossmatching, a complete blood count, and electrolyte levels.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition isn’t critical, take a thorough history. Ask about the pain’s onset and apparent precipitating events. Have him describe the pain’s location, intensity, pattern, and duration. Find out if anything aggravates or alleviates it.

Ask the patient about changes in his normal pattern of fluid intake and urine output. Explore his history for a urinary tract infection (UTI) or obstruction, renal disease, or recent streptococcal infection.

During the physical examination, palpate the patient’s flank area and percuss the CVA to determine the extent of pain.