- •Contents

- •List of Figures

- •List of Tables

- •List of Contributors

- •Preface

- •1 Research Styles in the History of Economic Thought

- •2 Ancient and Medieval Economics

- •4 Mercantilism

- •5 Physiocracy and French Pre-Classical Political Economy

- •8 Classical Economics

- •11 The Surplus Interpretation of the Classical Economists

- •12 Non-Marxian Socialism

- •13 Utopian Economics

- •14 Historical Schools of Economics: German and English

- •15 American Economics to 1900

- •22 Keynes and the Cambridge School

- •24 Postwar Neoclassical Microeconomics

- •25 The Formalist Revolution of the 1950s

- •26 A History of Postwar Monetary Economics and Macroeconomics

- •28 Postwar Heterodox Economics

- •31 Exegesis, Hermeneutics, and Interpretation

- •34 Economic Methodology since Kuhn

- •Name Index

- •Subject Index

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

61 |

|

|

C H A P T E R F I V E

Physiocracy and

French Pre-Classical

Political Economy

Philippe Steiner

5.1INTRODUCTION

The final part of Louis XIV’s reign saw the development of major economic works with the contributions of Pierre de Boisguilbert (1646–1714) and Sébastien le Prestre, Marshall Vauban (1633–1707). A member of the local administration, the former wrote several pamphlets and booklets on economic administration (taxation, grain trade, and money) in which several market mechanisms were studied with great insight (Boisguilbert, 1966). Following the Jansenist approach

– according to which a good society may work well without virtuous behavior, since self-love is enough – Boisguilbert explained that wealth did not result from benevolence and charity, but from self-interest (Faccarello, 1986). Since corn does not grow like mushrooms, the price paid to the farmer should be high enough to cover the cost of production. With the concept of proportionate prices (prix de proportion), Boisguilbert pointed out that markets were connected by money flows: an expense for the buyer of grain is a revenue for the farmer. Thus, lowering the price of corn – a usual claim in periods of grain shortage – was a dangerous economic policy, since farmers would stop producing corn. More generally, Boisguilbert warned the government that any active policy on the grain market (for example, buying corn abroad) would give birth to anticipations (a likely shortage) and would prevent the policy from being effective (buyers eager to obtain a stock of grain would increase their demands, prices would rise, and a shortage would be created). Free trade thus appeared to be a sound policy. In line with English political arithmetic, Marshall Vauban, a great military engineer,

62 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

grounded his proposal for a new fiscal system, known as La dîme royale (Vauban, 1992 [1707]), on calculations. He suggested that an increase in the military and economic power of the king could be achieved together with an increase in the well-being of the population through an appropriate taxation system: the state would collect a moderate percentage (from 5 to 10 percent) of the agricultural produce, whereas commerce and industry would contribute a very small amount to the royal revenues.

These reflections on economic affairs likely were related, on the one hand, to the poor situation of the realm (with a series of bad weather conditions in 1693–4, 1698–9, and 1709–10, accompanied by famines and a huge mortality – up to one-tenth of the population) and, on the other, to continuous warfare with the continental power (the Austrian Empire) or with the maritime power (The Netherlands). The situation in the 1750s was again marked by military conflict – the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) between France and England – but, as recent French historiography has demonstrated (Perrot, 1992; Théré, 1998), economic affairs were then a public concern.

First, several journals appeared, such as the Journal Œconomique (1751–72), the

Journal du commerce (1759–62), the Journal de l’agriculture, du commerce et des finances

(1765–74), and the Ephémérides du citoyen (1767–72; second series 1774–6). The first promoted agronomy and pushed for more rational husbandry; and the second, in which one may find influences from Cantillon’s work, was devoted to the science of commerce; whereas the last two were partially or completely dominated by the physiocrats. Secondly, the Intendant du commerce, Jacques Vincent de Gournay (1712–59), gathered a group of young men, including François Véron de Forbonnais (1722–1800) and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–81), in order to promote the study of commerce. Finally, the number of economic publications exploded after the middle of the century (table 5.1), the authors coming from all of the enlightened strata of French society: out of 1587 authors during the period 1750–89, about 10 percent were landowners, farmers, or manufacturers, 10 percent were ecclesiastics, and 6.5 percent were military officers, but the vast majority came from intellectual strata, with educators and men of letters (14.5 percent), lawyers, judicial officers, or financial magistrates (21 percent), or doctors and surgeons (6.5 percent).

This very active period in French political economy was dominated by François Quesnay and Turgot, whose work we will now consider in greater detail.

Table 5.1 Ten-yearly movements in economic publications, 1700–1789

|

1700 – 10 1710–20 1720–30 |

1730–40 1740 –50 1750–60 |

1760–70 1770–80 1780–89 |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

60 |

54 |

77 |

72 |

85 |

349 |

560 |

627 |

1284 |

(%) |

2 |

1.5 |

2.5 |

2 |

2.5 |

10.5 |

17 |

19 |

39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Based on Théré (1998), table 1.2.

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

63 |

|

|

5.2 QUESNAY AND THE ECONOMIC THEORY OF

AN AGRICULTURAL KINGDOM

François Quesnay (1694–1774) began his career as a surgeon, and then became a physician, working for the nobility and finally at the court in Versailles, where he was the protégé of Mme de Pompadour, the favorite of the king, Louis XV (Weulersse, 1910). He was well established in his profession, a member of the Académie des sciences (Paris) and of the Royal Academy of Sciences (London), and author of several books on medical subjects. Why he left this domain to become an economic thinker remains unclear.

The first step came with a new, enlarged, edition of his Traité de l’œconomie animale (Quesnay, 1747), in which he introduced considerations related to the theory of knowledge and rational behavior. He critically examined major philosophers of the day (Nicolas Malebranche and John Locke) in order to deliver his own interpretation of Condillac’s sensualism, to which he added the concept of order borrowed from Malebranche’s Cartesianism. This approach was reassessed in his first contribution to the Encyclopédie (“Evidence,” 1756), in which Quesnay stressed the difference between self-interest and enlightened self-interest or rational behavior, the one needed amongst landlords and the administration in order to reach the state of bliss.

The second and decisive step came when Quesnay wrote five papers (“Fermier,” “Grains,” “Hommes,” “Impôts,” and “Intérêt de l’argent”) to be published in the Encyclopédie: due to difficulties with the royal censorship, only the first two papers were published; nevertheless, all of them circulated and the last one appeared in the Ephémérides du citoyen in 1765. Quesnay then met the Marquis de Mirabeau (1715–89), whose fame was high after the publication of L’ami des hommes (1756–60), and turned the populationist into a fierce advocate of the new science. They jointly wrote two major books (Théorie de l’impôt in 1760 and Philosophie rurale in 1763) and a school grew up, with Pierre-Samuel Dupont de Nemours (1739–1817), l’Abbé Baudeau (1730–92), whose journal (Ephémérides du citoyen) became the journal of the school, and Pierre-Paul le Mercier de la Rivière (1727– 1801), whose book (L’ordre naturel et essentiel des sociétés politiques, 2001 [1767]) gave a general and methodical exposition of the whole doctrine. At their height, the physiocrats were sufficiently influential to promote a free trade policy, with an Act passed in 1764 concerning the freedom of the grain and flour trade.

5.2.1Economic policy, the price of grain,

and taxation

In the papers written in the years 1756–7, Quesnay was busy with economic government, defined thus:

The state of the population and of the employment of men is therefore the principal matter of concern in the economic government of states, for the fertility of the soil, the market value of the products, and the proper employment of monetary wealth

64 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

are the results of the labour and industry of men. These are the four sources of abundance, which co-operate in bringing about their own mutual expansion. But they can be maintained only through the proper management of the general administration of men and products; a situation in which monetary wealth is valueless is a clear evidence of some unsoundness in government policy, or oppression, and of a nation’s decline. (Quesnay, 1958, p. 512; Meek, 1964, p. 88; emphasis in the original)

He strongly rejected the economic policy of the French kingdom, a policy too close to the commercial interest, what Quesnay labeled the merchant’s system (le système des commerçants, Quesnay, 1958, p. 555), with monopolies, chartered companies, and the like (ibid., p. 523). Mesmerized by Amsterdam, with its commercial and monetary wealth, French governments since the time of Colbert, the great minister of Louis XIV, had been misled. Dutch economic government did not fit the French situation, claimed Quesnay, since The Netherlands was a commercial republic with few lands, whereas France was an agricultural kingdom, a large country with a rich soil, in need of an economic policy that favored a large volume of agricultural production that could be sold at a good price (bon prix).

In order to ground his view on economic policy, Quesnay reconsidered some basic theoretical issues. In “Hommes” and in chapter VII of the Philosophie rurale, he made a distinction between use value and monetary value, the latter being the true subject matter of political economy. Wealth is then defined as the goods exchanged on the market against money, in conformity to their value (ibid., p. 526); however, he had no explicit theory of value and price formation. He noted that use value cannot explain market value, since the latter is continuously changing whereas the former does not, but he contented himself with stating that prices were evolving according to a large number of unspecified circumstances (ibid., p. 526). He later urged his adversaries to write an “Essay on prices” that would offer “a fundamental contribution in order to close the discussions in this domain” (ibid., p. 750). Quesnay overcame the lack of a theory of price by presenting a large number of specific prices combined in an insightful comparison between two economic governments, autarky and free trade (Vaggi, 1987; Steiner, 1994, 1998b), the core of which is given in two tables, here presented in a slightly modified form (table 5.2).

In a manner reminiscent of Cantillon’s definition of the entrepreneur (Cantillon, 1997, pp. 28–33), Quesnay’s farmer has to assume certain costs (the fundamental price or the production cost plus rent – accordingly, the fundamental price is a production price, since it contains a part of the net surplus) with uncertain revenues, depending on the climate and the actual economic policy. Given a stable distribution of the climate over a period of five years, the model focuses on prices and revenues, the economic policy being considered as the independent variable.

In the absence of free trade, current market prices within the nation differ from international prices and, except in the case of a bad harvest, the former is below the latter since the nation is rich and fertile; this situation is detrimental to both the seller (the farmer, since the merchant is left out) and the buyer (the final consumer). The consumer is supposed to buy the same quantity of corn (three units) each year in order to fulfill his basic needs. Accordingly, the current sum

|

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

65 |

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

Table 5.2 Economic government: autarky and free trade compared |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Autarky |

|

|

Free trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fundamental |

Quality |

Quantity |

|

Market |

Net surplus |

Market |

Net surplus |

price |

of the |

produced by |

|

prices, pt |

(in livres) by |

prices, p’t |

(in livres) by |

(in livres) |

climate |

unit of land, qt |

(in livres) |

unit of land |

(in livres) |

unit of land |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Plentiful |

7 |

10 |

–4 |

16 |

28 |

|

|

Good |

6 |

12 |

–2 |

17 |

28 |

|

74 |

Average |

5 |

15 |

1 |

18 |

6 |

|

|

Poor |

4 |

20 |

6 |

19 |

2 |

|

|

Bad |

3 |

30 |

16 |

20 |

–14 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Based on Quesnay (1958), pp. 532–3.

spent, or the consumer price, is equal to the quantity times the market price (pt) and the average cost of one unit of corn for the consumer, or the average consumer price, is 1/5 Σpt = 17.4 livres, according to Quesnay’s data. The situation is substantially different for the producer, since his annual revenue depends on prices and on the quantity produced (qt); accordingly, the average revenue that he gets for one unit of corn, or the average producer price, is Σptqt/Σqt = 15.48 livres. The same unit of corn costs more to the consumer than it yields to the producer; this is due to the price–quantity relationship, which is the core element of the model. Quesnay’s price–quantity relationship is a King–Davenant relation, with a weaker price elasticity (Steiner, 1994), which means that prices overreact to a fall in production. Finally, in the situation of autarky, net product (annual gross revenue minus fundamental price) is positive but, on the one hand, there is an inverse relation between net product and quantity produced and, on the other hand, producers and consumers have a direct opposition of interest: when the crop is plentiful, the consumer enjoys abundance and low prices, which means a loss for the producer, whereas the producer gets a large surplus when the crop is bad – that is, when there is a shortage and a high price.

Under free trade policy, with the broadening of the market, a different price– quantity relationship is at work together with a higher current price (pt′), except in the case of a bad harvest. Nevertheless, the average consumer price is not substantially modified (from 17.4 livres to 18 livres) due to the disappearance of the very high price that was formerly associated with bad harvest. Meanwhile, the average producer price jumps from 15.48 livres to 17.6 livres, and the net product is greater, with 50 livres for 5 years instead of 17 livres formerly. Finally, consumers and producers have the same interest in a plentiful harvest, since the inverse net product–quantity produced relation has disappeared with the King– Davenant price–quantity relation.

Without the help of a theory of price, Quesnay produced a fine piece of economic analysis showing the benefits associated with free trade. The improvement

66 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

in the situation of the farmer comes from a small increase in the average price of corn, which means that wages have no reason to rise substantially, permitting the export sector to remain competitive abroad. Furthermore, if one takes the size of the net product as the yardstick for evaluating policy, the system of merchants appears to be disastrous: in order to get a small net product from commerce, based on a low cost in manufacturing and in maritime commerce (Steiner, 1997)

– that is, with a low price for corn and low wages – the French kingdom deprives itself of the large agricultural net product associated with a free trade policy.

According to Quesnay, farmers constitute the core of the productive class, since the level of production depends on the size of their capital once the correct economic policy is implemented. In “Fermier,” Quesnay explained that when farmers are poor (do not have capital of their own), they cannot produce with a good technique (grande culture), which is characterized by a net product to circulating capital ratio equal to 100 percent, and they must content themselves with a less productive technique (petite culture), with a lower ratio equal to 35 percent. The productive sector (agriculture) must be given the priority over the sterile one (manufacture), and thus Quesnay asked for institutional reforms in favor of this class, because their wealth was the basic fuel for the recovery of the French nation. In a period during which France was involved in a costly war against England, this policy would appeal to a kingdom in need of the financial resources necessary to cope with the high costs of maritime and continental wars (Steiner, 2002). Nonetheless, it raised some important problems related to the distribution of wealth.

Rent is determined though a bargaining process between the landlord and the farmer, but Quesnay did not introduce any specific revenue for the farmer. In his papers, farmers are supposed to pay both the taxes (whether to the state or to the Church) and the rent out of the net product; a profit could be conceived as the remaining part of the net product accruing to the farmer. In the following period, Quesnay went in a different direction with the single-tax doctrine.

This fiscal doctrine was aimed at diminishing the economic and social costs of fiscal administration, notably for the people living in the countryside, through a tax directly paid by those who were the effective taxpayers, the landlords. Quesnay’s single tax doctrine was a bold policy according to which farmers would pay the whole net product to the landlords, so that the latter could pay all of the taxes to the king and the Church. Then farmers would no longer fear the tax administrators and their capital would be free of any threat, as would be the agricultural net product that was so important for restoring the nation. The theoretical cost of this solution was important: from an analytic point of view; this meant that there was no room for a genuine concept of profit, since all of the surplus was paid as rent to the landlords. In this respect, the only possible remaining profit was the temporary profit that the farmer would retain as long as the productivity of his farm was enhanced, but he had yet to bargain anew his lease with the landlord (Meek, 1964; Eltis, 1975). In Philosophie rurale, Quesnay, followed by Dupont’s De l’importation et de l’exportation des grains (1910 [1764]), used this temporary profit argument to explain how farmers would find the necessary capital for progressively restoring the agricultural sector: as soon as a

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

67 |

|

|

free trade policy was implemented, farmers would receive a larger revenue while paying rent on the former and less profitable basis; this extra revenue could be invested, permitting them to use more efficient techniques (Eltis, 1996).

The political cost of this solution was high, since it demanded that landlords, many of whom were members of the nobility, pay the taxes. Indeed, Quesnay carefully explained that his tax system was the best solution for them, since, directly or indirectly, taxes were being paid by them. It is difficult to believe, however, that they would have welcomed such a proposal, at least without any political compensation in terms of the rights of citizenship and political representation. It is true that the physiocrats were looking for such political representation (Charles and Steiner, 1999), but they were not very successful in this respect.

5.2.2The Tableau économique: capital and

the circulation process

Quesnay devoted much effort to understanding the functioning of a large agricultural kingdom in which the government has implemented free trade: the Tableau économique was the result of this effort.

In line with his theory of knowledge, Quesnay considered that genuine economic science should be grounded on sensations; or, more precisely, on facts grasped through a quantitative dimension. In this respect, Quesnay was close to Petty’s political arithmetic, in which the latter characterized his approach by the use of weights and numbers instead of superlatives.

Empirical relevance was a methodological prerequisite for accurate economic calculations, out of which evidence could make its way through the misleading arguments that vested interests often spread about during economic debates. As Quesnay put it in the preface of the Philosophie rurale, “Calculations are to the science of political economy, what bones are to the human body.” Conscious of the specificity of the social sciences, he added a rhetorical dimension: “It takes calculations to critique calculations” (Quesnay, in Mirabeau, 1763, pp. xix–xx). Nevertheless, calculation was limited to arithmetic and geometry; in his book on mathematics Quesnay (1773, vol. 5, pp. 26–7) explained that calculus was a metaphysical tool, free of any sensationalistic basis, and useless in political economy.

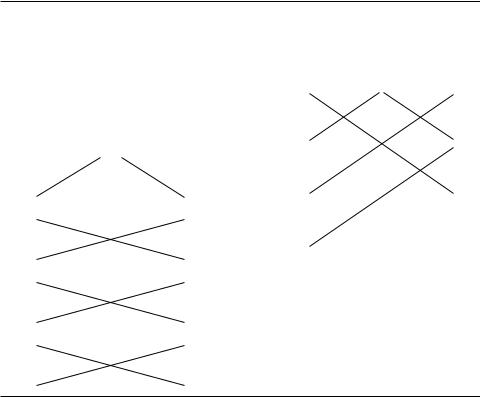

Empirical accuracy and rhetorical advantage were important aims, but Quesnay added a theoretical one to his approach as far as his economic table was concerned. In the final remark in his first edition, he told the reader that, by hypothesis, agricultural techniques permitted the net product to circulating capital ratio to reach 100 percent but, whatever the actual ratio, wrote Quesnay, the principles at work in the table were correct (Quesnay, 1958, p. 673). As in Ricardian “strong cases,” the economic table was constructed to explain the functioning of basic principles. Which ones? Two kinds of economic table can be distinguished (Cartelier, 1984; Herlitz, 1996), even if, as indicated above, one can make room for a third kind using the disequilibrium approach in Philosophie rurale, “Premier problème économique” (1766) and “Second problème économique” (1767) (Eltis, 1996). The first kind is given in the three successive editions of the zig-zag

68 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

Table 5.3 Two economic tables: the zig-zag (1758–9) and the formula (1765)

|

|

|

The zig-zag |

|

|

|

|

The arithmetic formula |

||||||

Productive |

Landlords’ |

Sterile |

Productive |

Landlords |

Sterile |

|||||||||

expenses |

expenses |

expenses |

class |

|

|

class |

||||||||

|

|

|

Revenue |

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

2 |

1 |

|

||

Annual |

|

|

Annual |

|

a |

b |

|

|||||||

advances |

|

|

advances |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|||||||

|

600 reproduce |

600 |

300 |

|

|

c |

d |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

300 reproduce |

300 |

300 |

|

|

|

e |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

Total: 2 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

150 reproduce |

150 |

150 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

75 reproduce |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

75 |

75 |

|

Total: 5 |

|

|

|

|

||||||

formulated in the years 1758–9; the second is limited to the “Analyse de la formule arithmétique du tableau économique.”

In the zig-zag (table 5.3), the major concern was spending. The formalization shows how the rent paid by farmers to landlords (600 livres) is successively received and spent by two other classes (the agricultural or productive class and the artisan or sterile class), giving rise to the same amount of net product (600 livres). The initial expenditure of the landlords is divided into two equal sums (300 livres), one for the luxury consumption of food and the other for the luxury consumption of furniture, clothes, and the like. Then, the sterile class spends half of the money received (150 livres) to buy food and raw materials from the productive class; the other 150 livres is used to reconstitute the capital of the sterile class, eventually with some goods being bought abroad (Meek, 1964). The productive class spends 150 livres to get manufactured goods from the sterile class, whereas the 150 livres that are left are spent within the sector. The two classes go on spending half of the money received until all of the money is finally spent. When this spending process is complete, the gross total revenue received by the productive class (300 livres from the landlords and 300 livres from the sterile

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

69 |

|

|

class) is equal to the circulating capital (or “annual advances” in Quesnay’s language) of this class; consequently, the reproduction of the capital generates a net product of an equal amount, as shown in the central column of the table. In line with Keynesian insights (a multiplier equal to two), Quesnay showed that the sums spent by the landlords are crucial: the various classes are related by flows of money and, to use Michal Kalecki’s language, those in possession of money (landlords) earn what they spend, whereas others spend what they earn. Nevertheless, as recognized by François Véron de Forbonnais (1767), who carefully studied this version of the economic table, the table is not correct as far as the reproduction of capital is concerned. In the table, the gross revenue (600 livres) and the net revenue (300 livres) of both the sterile class and the productive class are equal, a result clearly at variance with the principle of exclusive productivity of the productive class. Aware of this fact, in his commentary on the table, Quesnay introduced an extra flow (300 livres) from the sterile class to the productive class in such a way that the latter obtain a net revenue equal to the initial amount of the net product (600 livres). This is a clear sign that the economic table cannot prove the exclusive productivity of one sector alone, but that this exclusive productivity was only an hypothesis – a weak one, according to many contemporaries (Galiani, 1984 [1770]).

Hence, the formula can be considered as an attempt to overcome the remaining difficulty in the zig-zag: how the reproduction of capital (circulating and fixed capital, money capital) results from the monetary flows between the three classes. At the outset, the productive class has two units of money, and has advanced ten units of fixed capital and two units of circulating capital; the sterile class has only one unit of circulating capital; this capital generates a gross production of five units of agricultural goods and two units of manufactured goods. Then the productive class pays the rent or net produce to the landlords, with the two units of money. The circulation process begins with (a) landlords spending half of their rent to get luxury food from the farmers (one unit) and (b) luxury goods from the artisans (one unit); thereafter, artisans buy one unit of agricultural produce for their food (c), while farmers reconstitute their fixed capital with one unit of manufactured goods (d), since this capital suffers from an annual depreciation of one-tenth of its value. Finally, (e) artisans spend this unit of money buying one unit of agricultural produce in order to reconstitute their circulating capital.

Summing up, the landlords have spent all the money received as rent in order to consume; the artisans have sold two units of manufactured goods, and have spent a corresponding amount of money in order to buy food and to reconstitute their capital; the circulation process has thus allowed these two classes in the end to get what they had in the beginning. What about the productive class? They have sold three of the five units of the agricultural goods produced, they have bought the necessary manufactured goods in order to reconstitute their fixed capital, while the two remaining units of agricultural goods reconstitute their circulating capital. Finally, the money capital is reconstituted as well, since they have two units of money equal to their gross revenue (three units) minus their expenses (one unit). Every form of capital is thus reproduced, in value and in use

70 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

value, by the class that formerly possessed it: the process of circulation has reproduced the initial conditions of production.

The effective spending of all of the money received by the various classes is a crucial hypothesis; however, Quesnay adds a further hypothesis, since landlords have to spend half of their rent in each sector. If they do not, if they spend more in manufactured goods than in food, then, according to Quesnay, the reproduction of agricultural advances cannot be achieved and a process of decline necessarily ensues. Modern analysis does not confirm this point, since if artisans were to go on spending all their money buying agricultural produce, agricultural revenue would be left unchanged and the only effect would be a modification of the proportion of both sectors in the economy (Cartelier, 1984, 1991).

It was a substantial tour de force to set out the circulation process of a whole nation within three nodes and five lines. It is no surprise that the formula has since attracted the attention of major theoreticians: Karl Marx, when he built his reproduction model (Gehrke and Kurz, 1995); Joseph Schumpeter, when he praised Quesnay for this first attempt to set forth the general equilibrium approach, which he considered as the economists’ Magna carta; and Wassily Leontief, when he modeled the American economy with his input–output table.

5.3TURGOT: TOWARD A THEORY OF A CAPITALIST ECONOMY

After brilliant academic studies, Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot gave up his anticipated ecclesiastical career and became a member of the high governmental administration. He was personally acquainted with Gournay, traveling with him during the years 1756–7; his first notes on trade, wealth, and money, and several entries (“Etymologie,” “Existence,” “Expansibilité,” “Foires,” and “Fondation”) for the Encyclopédie date from that period. Appointed intendant in Limousin, one of the poorest parts of France, a position in which he remained from 1761 to 1774, he became an emblematic figure of the reformer. Nevertheless, he often stayed in Paris and was well acquainted with the physiocrats, Dupont in particular, and other Parisian salons (he met Adam Smith during the latter’s stay in Paris in 1765) through which he met Condorcet, one of his major intellectual heirs. During this period, he wrote his major essays in political economy: on taxes (Observations sur les mémoires de Graslin et de Saint-Péravy, 1767), on the grain trade (Lettres au Contrôleur général sur le commerce des grains, 1770), on money and interest (Valeur et monnaie, 1769; Mémoire sur les prêts d’argent, 1770), and his most comprehensive book, Réflexions sur la formation et la distribution des richesses (1766). Louis XVI appointed him Contrôleur général and he served from August 1774 to May 1776: he reestablished the freedom of the internal grain trade, which had been suppressed by the former Contrôleur général (Abbé Terray), and he worked for the freedom of the labor market.

A correct assessment of Turgot’s political economy must cope with his relation to physiocracy. Recent research emphasizes his differences with Quesnay’s political economy (Faccarello, 1992; Ravix and Romani, 1997), suggesting that Turgot was directly in line with classical political economy (Groenewegen, 1969, 1983b;

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

71 |

|

|

Brewer, 1987), notably for his theory of capital. Turgot’s Lettres au Contrôleur général sur le commerce des grains offers a good opportunity to see his intellectual relations to Quesnay, while his theories of value and capital highlight Turgot’s originality. Hastily written in three weeks at the request of the Abbé Terray, Turgot endorsed Quesnay’s view of free trade.

5.3.1Markets and competition

Turgot made intensive use of Quesnay’s concepts of producer and consumer prices, fundamental prices, and net product; and, according to Dupont’s summary of one lost letter, Turgot used a table similar to Quesnay’s in “Grains” and “Hommes,” and endorsed those fundamental ideas according to which free trade offered what could be now labeled a Pareto-improving policy. However, he added new insights on the functioning of free trade.

Quesnay had explained why price volatility will diminish, but Turgot raised a new problem: How could one explain that free trade did not raise the average price of corn in France? Turgot argued that price would rise only due to a change between supply and demand. Internal demand had no reason to change, he said, since the consumer would not change the quantity consumed, and since, in the short run, there was no reason to believe that producers would change the quantity produced. What about foreign consumers? Are they not ready to buy a large quantity of French corn at a low price, leaving French consumers short of their basic foodstuff? Turgot discarded the common argument with which traditional thinkers opposed free trade: foreign consumers would not buy French corn unless its price fell below the international price to such an extent that the French price plus the profit of the capital of the merchant would be inferior to foreign prices. As simple as it may appear, this reasoning is quite original: it contains the basic principles of the theory of price and profits that were lacking in Quesnay’s approach. It also reveals that Turgot was in full command of the principle of spatial arbitrage between two marketplaces. Furthermore, his letters show that Turgot had benefited from Boisguilbert’s works, notably the concept of proportionate prices, as is clear from his analysis of the relations between the labor market and the grain market.

Turgot did not content himself with a static approach; he introduced the necessary outcome related to a higher average producer price. With the rise of the producer price, profits accruing to farmers give them the possibility of increasing production when it is in their interest. As a consequence, the demand for labor will rise, while the supply of grain will do the same: What will be the result of such a situation? With the rise in farmers’ demand for labor, a rise in either the number of wage earners or a rise in wages, or both, will ensue; in any case, there will be a rise in the demand for corn, facing the rise in the quantity produced. Turgot was not able to provide a solution to this dynamic system, but he argued that the two market prices (the wage rate and the price for corn) would be proportionate to each other, and would exist in an “advantageous equilibrium” in which wages would allow laborers to buy corn, and the price of corn would be high enough for farmers to make a profit on the cultivation of land:

72 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

Since society subsists, then as a rule the necessary proportion between the price of foodstuff and the price of labour must subsist. However, this proportion is not so strictly determined that it cannot vary and become around the most just and advantageous equilibrium. (Turgot, 1770; in 1913–23, vol. III, p. 315)

Indeed, though the proportionate-prices theory is not fully worked out, and there is no demonstration of the existence and stability of equilibrium, Turgot’s analysis of competition in terms of the relations between two markets was pathbreaking. Competition, wrote Turgot to Dupont (ibid., vol. II, p. 507), was a less abstract but simpler and more powerful principle than the economic table.

In the longer run, Turgot considers the case in which population growth becomes a condition of economic growth through a growing supply of labor in the nation, even though the lag between birth and capacity to work introduces some stickiness in the labor market. This growth, together with an increasing quantity of capital, ensures the possibility of economic growth, and is in line with the philosophy of progress that he had developed as early as his discourse in the Sorbonne in 1750 (Meek, 1973), and which he fully worked out in his four-stage theory in Reflections. Nevertheless, this growth is limited by natural constraints. In comments in two essays on indirect taxes, Turgot made a fundamental remark concerning the net product–capital ratio. Contrary to what Quesnay and the physiocrats had said, it is not possible to say that this ratio is constant:

If the soil were tilled once, the produce would be greater; tilling it a second and third time would not just double or triple, but quadruple or decuple the produce, which will thus increase in a much larger proportion than the expenditure, and this would be the case up to a certain point, at which the produce would be as large as possible relative to the advances. Past this point, if the advances are still further increased, the product will still increase, but less so, and continuously less and less until an addition to the advances would add nothing further to the produce. (Turgot, 1767; in 1913–23, vol. II, p. 645; Groenewegen, 1977, p. 112)

To this very clear statement regarding nonproportional returns, Turgot adds a further remark, according to which the best economic situation is not the one determined by the best production ratio (net product on capital), since it is likely that a further quantity of capital would provide enough net product to be a valuable investment. However, since Turgot did not introduce the price of the product, there was, once again, no precise determination of the equilibrium point.

5.3.2Value, capital, profit, and interest

In Valeur et monnaie, Turgot coped with an intricate problem in the theory of value: How can a social evaluation – the current price – be the result of individual evaluation? Like several other economists of the period (Graslin, 1911 [1767]; Condillac, 1980 [1776]), Turgot developed a theory of value grounded on utility. First, with the sensualistic conception of man as a bundle of desires,

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

73 |

|

|

man’s relation to wealth is conceived in terms of needs and utility. Secondly, Turgot considers a pure exchange model in which two agents have a fixed initial stocks of two goods, corn and wood: the process begins with the ordering of the goods by each agent according his perception of scarcity (rareté); that is, the utility of the goods balanced by the difficulty of obtaining them. Out of this preference ordering, there appears an estimated value (valeur estimative) with which each agent relates the utility of the good to him and the disutility of obtaining one unit of the good; indeed, the estimated value of one unit of corn (wood) is smaller than the estimated value of wood (corn) for the agent whose initial endowment is in corn (wood). Exchange appears as a social relation, as a result of which agents are better off for two reasons: because they can exchange, which means that they can benefit from the higher productivity related to the division of labor (Turgot, 1913–23, vol. III, p. 93; Groenewegen, 1977, p. 144), and because they exchange less for more, in terms of estimated value. Thirdly, the bargaining process proper takes place: this process, considered as the working of competition, is capable of revealing the true price of the good; that is, the exchange ratio between corn and wood. This ratio, or appreciative value (valeur appréciative), is the social result of two subjective evaluations of the scarcity of goods. Since Francis Y. Edgeworth’s formalization of this process, we know that no single solution exists in this pure exchange model; Turgot’s own solution introduced something like an equity principle, according to which the difference between each agent’s estimated value of the good bought and the good sold is equal. Unfortunately, Turgot’s manuscript stops after a programmatic sentence according to which he would have considered the general case involving more than two agents and more than two goods.

Capital theory was Turgot’s second major achievement. Turgot considered his Reflections to be a general overview of the subject, while also claiming to have examined in detail the formation and the working of capital and the interest rate. As a matter of fact, while the physiocrats focused on Quesnay’s economic table – a tool that Turgot never made use of – he left out algebra, only considering the “metaphysics of the economic table” (Turgot to Dupont; in Turgot, 1913–23, vol. II, p. 519). Quesnay had done much on capital theory, but Turgot’s contribution was much more encompassing and accurate, since he considered all the forms of capital involved in the functioning of a commercial society, and because he had a clear concept of profit.

After the various agricultural stages, Turgot examines the commercial stage characterized by market relations; that is, by the value relations between goods and money (ibid., §XXXI–LXVIII). When members of commercial society receive more money than they spend for the satisfaction of their needs, and can spare this extra money, they transform a part of their revenue into capital. With this clear definition Turgot offers a simple explanation of the formation of capital, instead of the physiocratic one which is grounded on imperfections in the competition between farmers and landlords; furthermore, saving is no longer associated with hoarding; that is, a diminution in the circulation. According to his stage theory of progress (Fontaine, 1992), Turgot explains how wealthy people can earn a living out of land or out of money; this means that any amount

74 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

of accumulated wealth is equivalent to land whenever the revenue that the owner obtains at the end of the period is equal (ibid., §LVIII). How is profit explained? Like any entrepreneur investing capital, the farmer waits for three different elements, apart from the return of the value of the initial capital:

firstly, a profit equal to the revenue they would be able to acquire with their capital without any labour; secondly, the wages and the price of their labour, of their risk and their industry; thirdly, the wherewithal to replace annually the wear and tear of their property. (ibid., §LXII)

Thus profit is different from wages, since it is a revenue associated with the possession and the investment of capital, and has nothing to do with the revenue of labor. As far as rent and profit are concerned, Turgot explains that profit is a necessary part of the fundamental price, which means that profit does not belong to the net product; as in the Ricardian approach, rent becomes a residual category:

the surplus serves the farmer to pay the proprietor for the permission he has given to use his field for establishing his enterprise. This is the price of the lease, the revenue of the proprietor, the net product . . . and the profits of every kind due to him who made the advances cannot be regarded as a revenue, but only as the return of the expenses of cultivation, considering that if the cultivator did not get them back, he would be loath to risk his wealth and trouble in cultivating the field of another. (ibid., §LXII)

Turgot generalizes his approach to any form of investment, from land to moneylending, and explains that there exists a stable hierarchy of rates of return associated with the risk and the trouble assumed. These rates are in mutual relation, through a process of allocation of resources among the different investment opportunities and the basic mechanism of competition and economic equilibrium:

The different uses of the capitals produce, therefore, very unequal products; but this inequality does not prevent them from having a reciprocal influence on each other, nor for establishing a kind of equilibrium amongst themselves. (ibid., §LXXXVII)

In his paper on the interest rate, Quesnay had made a distinction between merchants and the rest of the population: while the former could lend at a rate that was freely determined by market forces, the rate of interest for the latter should be legally maintained below the rate of rent, in such a way as to make investment in land more attractive than financial activities. Turgot did not endorse such an approach: freely determined by the market forces, the rate of interest is inferior to the rate of profit in manufacture or agriculture because the risk and trouble assumed are less important; and there is no need for state intervention. A low interest rate is a clear indication that capital is abundant in a nation, and that entrepreneurs can expand their businesses since they can easily borrow the capital they need.

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

75 |

|

|

5.4 CONCLUSION

French political economy was particularly brilliant in the last period of l’ancien régime; this is especially true if one also considers the works written by the adversaries of the physiocrats, Ferdinando Galiani (1984 [1770]) and Jacques Necker (1986 [1775]), who objected to their abstract approach of political economy and to their way of implementing reform, discarding both political elements such as power relationships and disturbing anticipations on the market (Faccarello, 1998; Steiner, 1998a, ch. 2). However, the writings of Quesnay and Turgot were the most important and influential, whether for their contemporaries or for the generations that followed.

It is not an overstatement to say that Quesnay and Turgot offered the most innovative pieces of political economy prior to the work of Adam Smith. Many commentators on the great Scottish political economist have mentioned his debts to them (Gronewegen, 1969; Skinner, 1995), while others have stressed how much the two French economists contributed to the formation of classical political economy (Groenewegen, 1983b; Brewer, 1987; Cartelier, 1991; Faccarello, 1992). Their impact was obviously strong in France, whether on economic theory or on political debate. In the former domain, the works of Condorcet are important, at least for the movement toward social mathematics, in which Arrow’s impossibility theorem is found in a reasonably well developed form. In a different direction, one can find many links between Jean-Baptiste Say’s Traité d’économie politique (1803) and Turgot, through the influence of Pierre Louis Roederer, notably for his theory of value grounded on utility.

Among the major points debated in the following decades was the physiocratic theory of taxation: this is not by chance, since taxation links pure analysis and political reform. Furthermore, in that period of political turmoil, taxation was a strong political concern, since citizens were supposed to pay taxes. As a consequence, the “new science” of political economy, to use Dupont’s words, was directly involved in the transformation of political discourse. Physiocracy, Turgot included, had created a new political vision, grounded on self-interest, and opposed to Montesquieu’s and Rousseau’s visions grounded on honor or virtue (Charles and Steiner, 1999). In order to promote this vision of society, they were so eager to turn all the traditional elements of the social hierarchy upside down that Alexis de Tocqueville wittily considered them to have been major promoters of the revolutionary spirit in France.

Bibliography

Primary literature

Boisguilbert, P. de 1966: Pierre de Boisguilbert ou la naissance de l’économie politique. Paris: INED.

Cantillon, R. 1997: Essai sur la nature du commerce en général. Paris: INED.

Condillac, Etienne Bonnot, abbé de 1980 [1776]: Le commerce et le gouvernement. Genève: Slatkine. English translation, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

76 |

P. STEINER |

|

|

Dupont de Nemours, P. S. 1910 [1764]: De l’exportation et de l’importation des grains. Paris: Geuthner.

Galiani, F. 1984 [1770]: Dialogues sur le commerce. Paris: Fayard.

Graslin, J.-J. 1911 [1767]: Essai analytique sur la richesse et sur l’impôt. Paris: Geuthner.

Le Mercier de la Rivière, P.-P. 2001 [1767]: L’ordre naturel et essentiel des sociétés politique. Paris: Fayard.

Mirabeau, Victor Riquetti, marquis de 1760: Théorie de l’impôt. Paris.

——1763: Philosophie rurale. Amsterdam: Libraires associés.

——1999 [1758–60]: Traité de la monarchie. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Necker, J. 1986 [1775]: Sur la législation et le commerce des grains. Roubais: Edires. Quesnay, F. 1747: Essai physique sur l’œconomie animale. Paris, Cavelier.

——1773: Recherches philosophiques sur l’évidence des vérités géométriques. Amsterdam and Paris: Knapper et Delagnette.

——1958: François Quesnay et la Physiocratie, vol. 2. Paris: INED.

Turgot, A.-R.-J. 1913–1923: Œuvres de Turgot et documents le concernant. Paris: Alcan. Vauban, Sébastien le Prestre 1992 [1707]: La dîme royale. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale. Véron de Forbonnais, F. 1767: Principes et observations économiques. Amsterdam: Chez Marc

Michel Rey.

English translations

Groenewegen, P. 1977: The Economics of A. R. J. Turgot. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. —— 1983a: Quesnay “Farmers” and Turgot “Sur la grande et la petite culture.” Sydney: Univer-

sity of Sydney.

Kuczynski, M. and Meek, R. L. 1972: Quesnay’s tableau économique. London: Macmillan, for the Royal Economic Society and the American Economic Association.

Meek, R. 1964: The Economics of Physiocracy. Essays and Translation. London: George Allen & Unwin.

—— 1973: Turgot on Progress, Sociology and Economics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Secondary literature

Barna, T. 1975: Quesnay’s Tableau in modern guise. Economic Journal, 85, 485–96. Brewer, A. 1987: Turgot: founder of classical economics. Economica, 54(4), 417–28. Cartelier, J. 1984: Les ambiguités du Tableau économique. Cahier d’économie politique, 9,

39–63.

—— 1991: L’économie politique de Quesnay ou l’Utopie du Royaume agricole. In François Quesnay, Physiocratie. Paris: Flammarion, 9–64.

Charles, L. and Steiner, P. 1999: Entre Montesquieu et Rousseau. La Physiocratie parmi les origines de la révolution française. Etudes Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 11, 83–159.

Eltis, W. 1975: Quesnay: a reinterpretation. Oxford Economic Papers, 27(2), 167–200; 27(3), 327–51.

—— 1996: The Grand Tableau of François Quesnay’s economics. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 3(1), 21–43.

Faccarello, G. 1986: Aux origines de la pensée économique libérale: Pierre de Boisguilbert. Paris: Anthropos.

——1992: Turgot et l’économie politique sensualiste. In A. Béraud and G. Faccarello (eds.), Nouvelle histoire de la pensée économique, vol. 1. Paris: La découverte, 254–88.

——1998: Turgot, Galiani and Necker. In G. Faccarello (ed.), Studies in the History of French Political Economy. From Bodin to Walras. London: Routledge, 120–95.

PHYSIOCRACY AND FRENCH PRE-CLASSICAL POLITICAL ECONOMY |

77 |

|

|

Fontaine, P. 1992: Social progress and economic behaviour in Turgot. In S. T. Lowry (ed.),

Perspectives on the History of Economic Thought, vol. 7: Perspectives on the Administrative Tradition: From Antiquity to the Twentieth Century: Selected Papers from the History of Economics Conference 1990. Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar, for the History of Economics Society, 76–93.

Fox-Genovese, E. 1976: The Origins of Physiocracy. Economic Revolution and Social Order in Eighteenth Century France. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Gehrke, C. and Kurz, H. D. 1995: Karl Marx on physiocracy. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 2(1), 53–90.

Groenewegen, P. 1969: Turgot and Adam Smith. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 16(3), 271–87.

—— 1983b: Turgot’s place in the history of economics: A bi-centenary estimate. History of Political Economy, 15(4), 585–616.

Herlitz, L. 1996: From spending to reproduction. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 3(1), 1–20.

Larrère, C. 1992: L’invention de l’économie au 18e siècle. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Perrot, J.-C. 1992: Une histoire intellectuelle de l’économie politque. Paris: Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

Ravix, J.-T. and Romani, P.-M. 1997: Le “système économique” de Turgot. In Turgot,

Formation et distribution des richesses. Paris: Flammarion, 1–63.

Skinner, A. 1995: Adam Smith and François Quesnay. In B. Delmas, T. Demals, and P. Steiner (eds.), La diffusion internationale de la Physiocratie: 18e–19e siècles. Grenoble: Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 33–57.

Steiner, P. 1994: Demand, price and net product in the early writings of Quesnay. European Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 1(2), 231–51.

——1997: Quesnay et le commerce. Revue d’économie politique, 107(5), 695–713.

——1998a: Sociologie de la connaissance économique. Essai sur les rationalisations de la pensée économique (1750–1850). Paris: Presse universitaires de France.

——1998b: La “Science nouvelle” de l’économie politique. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

——2002: Wealth and power: Quesnay’s Political Economy of the agricultural kingdom.

Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 24(1), 91–110.

Théré, C. 1998: Economic publishing and authors, 1566–1789. In G. Faccarello (ed.), Studies in the History of French Political Economy. From Bodin to Walras. London: Routledge, 1–56.

Vaggi, G. 1987: The Economics of François Quesnay. London: Macmillan. Weulersse, G. 1910: Le mouvement physiocratique en France. Paris: Alcan.

78 |

A. BREWER |

|

|

C H A P T E R S I X

Pre-Classical

Economics in Britain

Anthony Brewer

The early development of economics in Britain falls into two distinct phases, before and after 1700. The seventeenth-century literature is almost wholly English and London-centered – mainly pamphlets or short books arguing a particular viewpoint or tackling a particular policy issue. There was a first flush of activity in the 1620s, a lull during the civil war and the Cromwellian republic, and sustained debate after 1660, reaching a climax in the 1690s, “the first major concentrated burst of development in the history of the subject” (Hutchison, 1988, p. 56). The London-centered debates of the 1690s came to an abrupt end at the turn of the century. The early eighteenth century saw little of note apart from two rather eccentric works by Law and Mandeville, and when the subject came to life again in the middle of the century the most important contributions came from Scotland. The economic thinking of the Scottish Enlightenment was less oriented to immediate policy issues and more concerned to locate economic issues in a wider ethical and historical framework.

It makes no sense to look at the economic writings of this time in isolation from their context. Britain’s situation was changing rapidly. At the start of the seventeenth century, England and Scotland were separate countries, and were in almost all respects marginal to the European system – prosperous but intellectually rather backward, and politically and militarily negligible on the European stage. Trade was dominated by Dutch ships and merchants, and Britain exported little but wool and woolen textiles. By the later seventeenth century things were changing on almost every front. England became the center of the new science, with the foundation of the Royal Society (1662) and the publication of Newton’s Principia (1687). New institutions were emerging, such as the Bank of England (1694). London overtook Amsterdam as a trading center, three naval wars with the Dutch opened the way to British control of the seas, and the Navigation Act of 1660 ensured that British ships and merchants were the beneficiaries. The

PRE-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS IN BRITAIN |

79 |

|

|

intense debates of the 1690s reflected the uncertainties of a period of change. By the early eighteenth century the pattern was set, as Marlborough’s victories on land made Britain, now united by the Act of Union of 1707, a major European power. The main aims of British policy – to maintain control of the seas and to prevent France dominating continental Europe – were set for a century or more (Wilson, 1984; J. Brewer, 1989). As Daniel Defoe observed in 1724, England was “the most flourishing and opulent country in the world.” The relative stability and continuing growth of the eighteenth century allowed a more reflective (and perhaps a more complacent) approach to economic issues.

6.1 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND:

THE MAKING OF A GREAT POWER

6.1.1Trade and the trade balance

To understand the voluminous literature on trade in seventeenth-century England, one must first understand the way contemporary Englishmen saw their situation relative to the Dutch. The United Provinces (the modern Netherlands) had finally established their independence in 1648 after a ferocious 80-year war against Spain. They were the trading and financial center of Northern Europe and, in per capita terms, the richest place in Europe. English merchants obsessively scrutinized the Dutch to discover the secret of their success. Thus, Child’s Brief Observations (1668) starts: “The prodigious increase of the Netherlanders in their domestick and forreign Trade, Riches, and multitude of Shipping, is the envy of the present and may be the wonder of all future Generations” but, he continued, the Dutch could be imitated “by us of this Kingdom of England” (1668, p. 3). If seventeenth-century writers thought that trade was the route to wealth, it was because of the Dutch example. By the eighteenth century, England had less cause to be envious and the debate subsided.

The seventeenth-century literature (or part of it) has often been labeled “mercantilist” (see Magnusson, ch. 4, this volume), but the writers of the time were too varied to be treated as a unified school of thought. There was indeed widespread support for active policies of one sort or another to promote English trade, usually at the expense of the Dutch and the French, but that is as far as it goes.

Applying modern methods of analysis to seventeenth-century conditions, it is not hard to make a case for “mercantilist” policies to promote Britain’s trade and market share. The big profits were in trading with the Far East and the Americas, using armed convoys and fortified settlements. Free trade in the modern sense was not an option. More generally, there were economies of scale and scope in entrepôt trade, and real opportunities to diversify England’s exports, with associated infant-industry arguments for protection. Seventeenth-century writers were dimly aware of these issues, but lacked the analytic apparatus to discuss them in terms acceptable to modern critics. Active policies were nonetheless adopted and did in fact have the desired results.

80 |

A. BREWER |

|

|

Many seventeenth-century debates focused on the balance of trade; that is, the excess (or shortfall) of export revenue over import spending. The basic idea can be traced back to the Middle Ages (Viner, 1937, p. 6). The metaphor of a “balance” seems to have been introduced by Malynes in 1601, in the phrase “overballancing” of trade. Much the most influential work on the subject was Thomas Mun’s England’s Treasure by Forraign Trade, written in the 1620s but published (in a quite different context) in 1664. The notion of an overall balance of trade was undoubtedly an analytic advance. Mun contrasted the overall balance tellingly with the balance on specific trades or the bilateral balance with any particular country, and used it to distinguish between gains to merchants, gains to the king, and gains to the nation as a whole. For a country that used metallic money and had no domestic sources of precious metals, the balance of trade really did determine the net inflow of specie and hence the change in the money stock (neglecting nonmonetary uses of gold and silver, which could be accounted for separately, and capital account transactions).

Unfortunately, it was fatally easy to confuse the balance of trade with the gains from trade, and to treat it as an aim in itself. The simplest way to fall into this trap would be to confuse wealth with money, or with precious metals. This is the charge that Adam Smith brought against Mun and other writers of the seventeenth century, and it is hard to acquit them completely (Viner, 1937, pp. 15–22). They did not think of precious metals as desirable in themselves, but they did, it seems, find it difficult to distinguish between the stock of money and a stock of wealth or capital. Thus, Mun argued that the “stock of a Kingdom” was like that of a private man who becomes richer by spending less than he earns and adding the difference to the “ready money in his chest” (1664, p. 5). In mitigation, one might point out that it was important to have reserves of internationally accepted metallic money in case of war, and that an inflow of money would stimulate the domestic economy, but one would then have to meet the objection that an inflow of money would raise the price level and make exports less competitive. Mun was aware of this possibility, but seems to have seen it as no more than a minor qualification, perhaps limiting the inflow of money rather than eliminating or reversing it. Not everyone accepted the balance of trade as a relevant policy aim and those who did could not agree on the policy conclusions. The issues involved were not sorted out satisfactorily until Hume (1752; see below).

The “mercantilist” writers of the seventeenth century are often described as opponents of free trade, but this is a misleading way to categorize them. Trade had always been taxed and regulated, and there was no established notion of free trade to act as a benchmark. What was new in the seventeenth century was not the regulation of trade but the development of a vocabulary and a framework for discussing the economic effects of regulation. In general, debates did not turn on freedom of trade as a general alternative to regulation or protection, but on the best policies to follow in particular cases. Thus Child (1693) recognized that where trade was free the cheapest suppliers would prevail, but since the Dutch were likely to be cheapest he saw that as an argument against free trade, while Barbon (1690) was against the prohibition of imports to protect domestic suppliers but in favor of using high duties to have the same effect. Early in the century,

PRE-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS IN BRITAIN |

81 |

|

|

Misselden (1622) did indeed argue for free trade, but what he meant by it was the opening of monopolistic companies such as the East India Company to other (English) merchants. Where trade was “disordered” and “ungoverned,” however, it should be brought to order.

It was from precisely these “mercantilist” debates that the concept of free trade, in something like its modern sense, emerged at the end of the century; in, for example, North (1691) and Martyn (1701). North led up to the conclusion that “we may labour to hedge in the Cuckow, but in vain; for no People ever yet grew rich by Policies; but it is Peace, Industry, and Freedom that brings Trade and Wealth, and nothing else” (North, 1691, p. 28). North and Martyn, however, had little impact at the time. Ironically, the main protective legislation, the Navigation Act, was progressively amended to make it more effective and was enforced more rigorously thereafter, while tariffs were raised significantly to raise revenue for military purposes. The case for free trade emerged just as trade was becoming less free.

6.1.2Money and the interest rate

Money was a perennial topic of discussion for a number of reasons. Money consisted of coins at that time, and the English coinage was in a very poor state because of wear and clipping. By the time of the eventual recoinage in 1696, coins had on average fallen to half their supposed weight. Gresham’s Law (named after Sir Thomas Gresham, advisor to Queen Elizabeth), that “bad money drives out good” because it pays to pass on coins with a low metal content and melt down better coins for the metal, was at work – the mint issued full weight coins, but 99 percent vanished from circulation. Consideration of the amount of money needed for circulation naturally led toward seeing the economy as a single whole, while consideration of changes in the money stock connected it to the trade balance and the relation between price levels in different countries. Fluctuations in the relative value of gold and silver also posed problems.

The interest rate was also an issue. In medieval Europe, “usury,” or lending at interest, had often been forbidden, at least in theory. By the seventeenth century, financial markets were becoming quite well organized but the law still set a maximum to interest rates. Repeated proposals to lower the maximum legal rate to what would certainly have been an unsustainably low level came very close to being passed in the 1690s. There were at least three views about interest rates: (a) that they reflected the “plenty or scarcity” of money, providing a possible motive for aiming at a positive trade balance to increase the money stock and allow lower interest rates; (b) that they depended on supply and demand of loans, and hence on net saving and on profit opportunities open to borrowers; and (c) the naive view that they could be set by legal fiat.

From the 1660s on, Josiah Child (1630–99) argued for reducing the interest rate by law, claiming that the rate had fallen as wealth increased, that it was lower in rich than poor countries, and that the time was now ripe for it to fall again. Low interest was the “causa causans” of prosperity because it would encourage merchants and farmers to expand their businesses, and it would also encourage

82 |

A. BREWER |

|

|

those with money to use it productively rather than simply letting it out at interest. There are clearly the makings of the notion of a demand and a supply function for investible funds here, but what is lacking is a clear notion of equilibrium between the two. Critics agreed that Holland had a low interest rate but pointed out that this was achieved without legal compulsion. Child replied that legislation might not be needed in Holland but it was in England, to allow England to match Holland as a center of trade.

The opposing case, and much more, is to be found in some of the most important economic writings of the seventeenth century, by John Locke (1632–1704). As early as 1668, he had prepared an unpublished draft on an earlier proposal to reduce interest rates, but he was forced into exile until after the revolution of 1688, when his main philosophic works appeared in quick succession, followed by a return to monetary issues in his Considerations (1691).

The basic idea of the quantity theory of money, that an increased quantity of money will lead to a fall in its value and a rise in the prices of goods, had been understood in general terms from early on. Locke argued it very clearly for an isolated economy. Whatever the quantity of gold and silver, it “will be a steady standing measure of the value of all other things” and can “drive any proportion of trade” (Locke, 1691, pp. 75–6), since a smaller quantity will be valued more highly. In modern terms, the nominal quantity of money is unimportant since prices adjust to it. In an open economy, however, he argued that the value of money was set at a world level. He thought that a country with a relatively small money stock would be at a disadvantage, but hovered between arguing that its prices would be low and its terms of trade unfavorable or that its trade would be limited and resources unemployed. Either way, he supported the common complaint that a shortage of money was a problem. Both Locke and his contemporary William Petty discussed the institutional determinants of the velocity of circulation and hence the amount of money needed to drive a given amount of trade. Both failed to grasp the specie-flow mechanism that Hume was later to state so clearly.

Locke thought that setting a low legal maximum to the interest rate would be ineffective in practice, and harmful if it were effective. In the absence of regulation, interest rates are determined by demand and supply, explained in what, to a modern reader, seem to be two different and conflicting ways. First, he claimed that when money is scarce, its price (the interest rate) must rise, like any scarce commodity. Interest is high when “Money is little in proportion to the Trade of a Country” (Locke, 1691, pp. 10–11). Secondly, he explained interest rates in terms of demand from borrowers who see profitable uses for capital and supply from those who have more wealth than they can (or want to) employ themselves, comparing it to rent, determined by the balance between potential tenants and landowners with land to rent out (pp. 55–7). The explanation of this apparent inconsistency between monetary and real theories of interest is that he seems to have confused wealth or loanable funds with the stock of circulating money. “My having more Money in my hand than I can . . . use in buying and selling, makes me able to lend” (p. 55). If there were a “million of money” in England, but debts of two millions were needed “to carry on the trade” – that is, if one million were

PRE-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS IN BRITAIN |

83 |

|

|

available for lending, but borrowers needed to borrow two millions – the interest rate must rise (p. 11). A low legal maximum would only make matters worse, because it would reduce the amount people were willing to lend, leaving the increased demand unsatisfied.

Dudley North (1641–91) presented an analysis (North, 1691) that has striking similarities to Locke’s on some points, but which is diametrically opposed to him on others. Interest rates, he argued, are determined by supply and demand for loans. As in Locke, the supply comes from those who have more resources than they want to employ themselves, and demand from those who see opportunities but need to borrow to take advantage of them. Unlike Locke, however, North saw that it was “stock” (capital or wealth) – not the quantity of money – that determined the supply. Low interest rates, as in Holland, are the result, not the cause, of wealth. Success in trade is the result of thrift and hard work, and leads to the accumulation of wealth and hence to a large supply of loans.

North argued that shortage of money is never a problem, focusing not on international movements of gold and silver but on movements of metal between coins in circulation and hoards of bullion or plate. A shortage of coin will bring out bullion and plate to be coined, while a surplus will be absorbed into hoards. He was able to support the argument by pointing out that large amounts of silver had been coined but that the new coins had disappeared to be melted down. The flow of money accommodates itself, he claimed, without any help from politicians.

6.1.3Political arithmetic and the state

Sir William Petty (1623–87) was trained as a doctor, became Professor of Anatomy at Oxford and Professor of Music at Gresham College, and was one of the founder members of the Royal Society. His key idea was to apply Baconian scientific method, the use of “number, weight and measure,” to social and political issues. This was “political arithmetic,” which aimed to provide impersonal, numerical facts as a basis for policy.

His great early achievement, the mapping of Ireland, illustrates his attitude. He had gone to Ireland as physician to Cromwell’s army, but he bid for and won the contract to survey the country. His map was an outstanding scientific and organizational achievement – perhaps the best map of any country at the time, finished on time and within budget – but its purpose was to help with the distribution of land to members of the victorious army. Petty himself emerged with extensive lands in Ireland. He was fiercely ambitious, and attached himself to whoever was in power, switching allegiance from Cromwell to Charles II at the Restoration (as, of course, many others did). His policy proposals were designed to strengthen the state, almost regardless of individual rights or interests. To make Ireland more secure and profitable for the British state, for example, he advocated transferring most of the Irish to England, to be absorbed into the much larger English population and eliminated as a separate people with a different language and culture.

The most important of the state’s resources is its population, so population estimates were the backbone of political arithmetic. The key work was the

84 |

A. BREWER |

|

|

Observations on the Bills of Mortality (1662), by John Graunt (1620–74). Petty certainly collaborated with Graunt and made similar calculations of his own, but their exact roles are unclear. Records of deaths and christenings showed that England as a whole produced a healthy surplus of births over deaths, but that London could only maintain and increase its population by migration from the rest of the country. Petty went on to use estimates of population and assumed per capita income levels to make pioneering estimates of total national income.

What use Petty made of these estimates, and the way they fit into the context of his time, can best be seen in his Political Arithmetick of 1676 (published posthumously in 1690; see Petty, 1899, pp. 233–313). He stated and supported ten conclusions, including:

That a small Country, and few People, may . . . be equivalent in Wealth and Strength to a far greater People and Territory. . . . That France cannot . . . be more powerful at Sea than the English or Hollanders. . . . That the People and Territories of the King of England are naturally near as considerable, for Wealth and Strength, as those of France. . . . That one tenth part, of the whole Expence of the King of England’s subjects; is sufficient to maintain one hundred thousand Foot, thirty thousand Horse, and forty thousand Men at Sea, and to defray all other Charges, of the Government. . . . That the King of England’s Subjects have Stock, competent, and convenient to drive the Trade of the Whole Commercial World. (Petty, 1899, pp. 247–8)

To see this in context, note that Parliament held the purse strings and would not allow Charles II the funds to pursue an active policy. He accepted a subsidy from Louis XIV, effectively making Britain a passive junior partner in French expansionary plans. Petty’s calculations showed that England need not be anyone’s junior partner. A small country it might be, but it could (and, under a new king, did) aim to control the seas and to dominate the trade of the “commercial world” (essentially the sea-borne trade of Europe). Petty estimated the requirements and the costs with striking accuracy. In the wars around the turn of the eighteenth century, Britain’s navy employed just about the 40,000 he proposed. The land army was smaller than his 130,000, but Britain was effectively paying for its allies’ troops as well. To do it, taxes had to rise from 3–4 percent of GNP to just about the 10 percent that Petty proposed (Holmes, 1993, p. 439). Petty saw no objection to allowing France to expand on the continent since England’s interests lay at sea (Petty, 1927, vol. 1, p. 262), but later generations disagreed.

Petty’s writings contain a few digressions that have attracted (perhaps disproportionate) attention. There is a suggestion of a labor theory of value (Petty, 1899, vol. 1, pp. 43, 50–1, 90) and a (conflicting) suggestion that the value of a good might be determined by the labor and land required to produce it, leading Petty to speculate about a “par” or value-conversion factor between labor and land (vol. 1, p. 181). This was later followed up by Cantillon, who referred to Petty’s par as “fanciful” (Cantillon, 1755, p. 43). There are also passages that describe some notion of a surplus of output over necessary subsistence (e.g., Petty, 1899, vol. 1, pp. 30, 118). Petty did not follow up any of these in a systematic way and

PRE-CLASSICAL ECONOMICS IN BRITAIN |

85 |

|

|