- •English Lexicology

- •Preface

- •Organization and Content

- •Contents

- •Part I: Introduction

- •1.2 Methods and Procedures of Lexicological Analysis

- •Part II: The Structure of the English Lexicon

- •2.1 Words and Their Associative Fields

- •2.2 Word Families

- •2.3 Word Classes

- •2.4 Semantic, or Lexical, Fields

- •3.1 Synchronic Approach to the Structure of the English Vocabulary

- •3.1.1 Common, Literary, and Colloquial layers

- •3.1.2 Neologisms

- •3.2 Diachronic Approach: Etymological Survey of the English Word-Stock

- •3.2.1 Definition of Etymology

- •3.2.2 English Lexemes of Native Origin

- •3.2.3 Borrowed, or Loan, Lexemes

- •3.2.4 Classification of Borrowings according to the Degree of Assimilation

- •3.2.5 Etymological Doublets and Triplets

- •3.2.6 Folk Etymology

- •Part IV: The Word

- •4.1 Defining a Word

- •4.2 Morphological Structure of Words

- •4.2.1 Free and Bound Morphemes

- •4.2.2 Roots and Affixes

- •4.2.3 Stems

- •4.2.4 Types of affixes

- •4.2.5 Derivational and Functional Affixes

- •Inflection of Derived or Compound Words

- •4.2.6 Cliticization

- •4.2.7 Internal Change/Alternation

- •4.2.8 Suppletion

- •4.2.9 Reduplication

- •Part V: Word-Formation

- •5.1 Derivation/Affixation

- •5.1.1 Types of Derivational Affixes

- •5.2 Stress and Tone Placement

- •5.3 Compounding

- •5.3.1 Classification of Compounds

- •5.3.2 Endocentric and Exocentric Compounds

- •5.4 Reduplication

- •5.5 Conversion

- •5.6 Blend(ing)

- •5.7 Eponyms

- •5.8 Backformation

- •5.9 Clipping

- •5.10 Acronyms and Abbreviations

- •Part VI: Semantics

- •6.1 Types of Semantics

- •6.2 Word-Meaning

- •6.3 Types of Meaning

- •6.3.1 Grammatical Meaning

- •6.3.2 Lexical Meaning

- •6.3.3 Denotative Meaning

- •6.3.4 Connotative Meaning

- •6.3.5 Differential Meaning

- •6.3 6 Distributional Meaning

- •6.4 Phonetic, Morphological, and Semantic Motivation of Words

- •6.5 Semantics and Change of Meaning

- •7.1 Similarity of Sense

- •7.2 Oppositeness of Sense

- •7.3 Sense Categories: Hyponymy

- •7.4 Sense Categories: Meronymy

- •7.5 Related Senses

- •7.6 Unrelated Senses: Homonymy

- •7.7 Semantic Deviance

- •Part VIII: Word Groups and Phraseological Units

- •8.1 Basic Features of Word-groups

- •8.2 Phraseology

- •8.3 Definition of a Phraseological Unit

- •8.4 The Criteria of Phraseological Units

- •8.5 Classification of phraseologisms

- •8.6 The Origin of Phraseological Units

- •8.6.1 Native Phraseological Units

- •8.6.2 Borrowed Phraseological Units

- •8.7 Semantic Structure of Phraseological Units

- •8.8 Phraseological Meaning

- •8.9 Semantic Relations of Phraseological Units

- •8.9.1 Similarity of Sense

- •8.9.2 Oppositeness of Sense

- •9.1 Differences in Vocabulary between American and British English

- •9.2 Spelling Differences between American and British English

- •7.3 Grammatical Differences between American and British English

- •Part X: Lexicography

- •10.1 Main Types of Dictionaries

- •10.1.1 Non-linguistic Dictionaries: Encyclopaedias

- •10.1.2 Linguistic Dictionaries

- •Imitation

- •Glossary

5.1.1 Types of Derivational Affixes

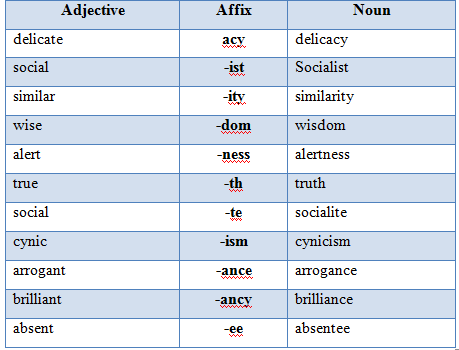

Derivational affixes are subdivided into two groups: class-changing and class-maintaining. Class-changing derivational affixes change the word class to which they are added. Thus, the verb achieve and the suffix –able create an adjective achievable. However, class-maintaining derivational affixes do not change the word class but change only the meaning of the word; for example, the noun adult and the suffix –hood create another noun adulthood, but now it is an abstract noun rather than a concrete noun. Class-changing affixes, when added to the stems, immediately change the class of the words, making them alternatively as a verb, a noun, an adverb, or an adjective. Therefore, derivational affixes determine or govern the word class of the stem. For instance, nouns may be derived from verbs or adjectives; adjectives may be derived from verbs and nouns; adverbs -- from either adjectives or nouns; and verbs may be derived from nouns or adjectives. English class-changing derivations are mostly suffixes. Noun-derivational affixes, which are also called nominalizers, are the following:

Verb-derivational affixes, also known as verbalizers, are used to coin verbs from other classes of words. Although verbs are used to form other classes of words, they are not readily formed from other parts of speech. The following derivational affixes build verbs from nouns and adjectives.

Adjective derivational affixes, or adjectivizers, are used to form adjectives mostly from the nouns and rarely from the verbs.

Adverb-derivational affixes, or adverbializers, are affixes which help form adverbs frequently from adjective and rarely from the nouns.

Class-maintaining derivations refer to those derivations which do not change the class of the stem to which they are added but change its meaning. Unlike class-changing derivations, which are mainly suffixes, class-maintaining derivations are prefixes and suffixes.

Noun patterns:

Verb patterns:

Adjective patterns:

English adverbs are not used to form words of other classes; therefore, there are no adverb patterns, as nouns, verbs, and nouns have.

5.2 Stress and Tone Placement

Sometimes a base can undergo a change in the placement of stress or tone to reflect a change in its category. There are some pairs of words in English in which a verb has a stress on the final syllable, while a corresponding noun is stressed on the first syllable.

5.3 Compounding

Compounding is a word-forming process which coins new words not by means of affixation but by combining two or more free morphemes. Compounding is a productive word-formation process. Actually, the parts of compound words may be only free morphemes, or the combination of free and bound morphemes. Compounds have more than one root, e.g., girlfriend, textbook, classmate, and others. Compounding is highly productive in the English language. It can be found in all the major lexical categories, such as nouns, adjectives, and verbs, but nouns are the most common type of compounds. The second element of a compound is usually the head, which carries the lexical meaning and determines the category of the entire word, whereas the first element only modifies the second element. For example, greenhouse is a noun just as house is. In addition, compounding can interact with derivation, e.g., abortion debate, in which the first word is derivation. Compounds consisting of two roots are the most numerous in the English language. Here are some examples of compounds, where nouns are initial elements: air (air-bed, air-brake, airbus, air-cell, air-conditioner, and others), arm (armchair), door (doorbell, doorjamb, and doormat), hand: (handball, handcar, and handcraft), eye: (eyeball, eyelash, eyeliner, eyesore, and eyewitness), heart (heartache, heartburn, and heartbreak), moon (moonbeam, moonboot, and moonlight). The following verbs are initial elements of compounds: pull (pullback and pullover), stand (standpatter and standpoint), swim (swimsuit and swimwear), and others. Adjectives as initial words include the following: big (bigfoot, bighead, and bighorn), brief (briefcase), short (shortbread, shortchange, and shorthand), high (highborn, highball, and highjack). Adverbs may also be as initial elements of compounds: down (downbeat, downburst, and downgrade), up (upbeat and upbound), and others.

There is a special type of compound which is formed by the combination of two bound morphemes. These types of compounds are called “neo-classical” (Jackson & Ze Amvela, 2007, p.95) compounds (bibliography, astronaut, pedophile, and xenophobia). New-classical compounding is a type of composition where the elements of a compound are not of native origin. They were mostly borrowed from classical languages such as Latin and Greek, e.g., bio-, auto-, tele-, -ology, and -phile. Such roots are considered bound roots. This creates a problem when distinguishing between neo-classical bound roots and affixes. Some examples of neo-classical compounds are the following: lexicology, morphology, semasiology, and others.