C1

.pdf

1

A R T B E F O R E

H I S T O RY

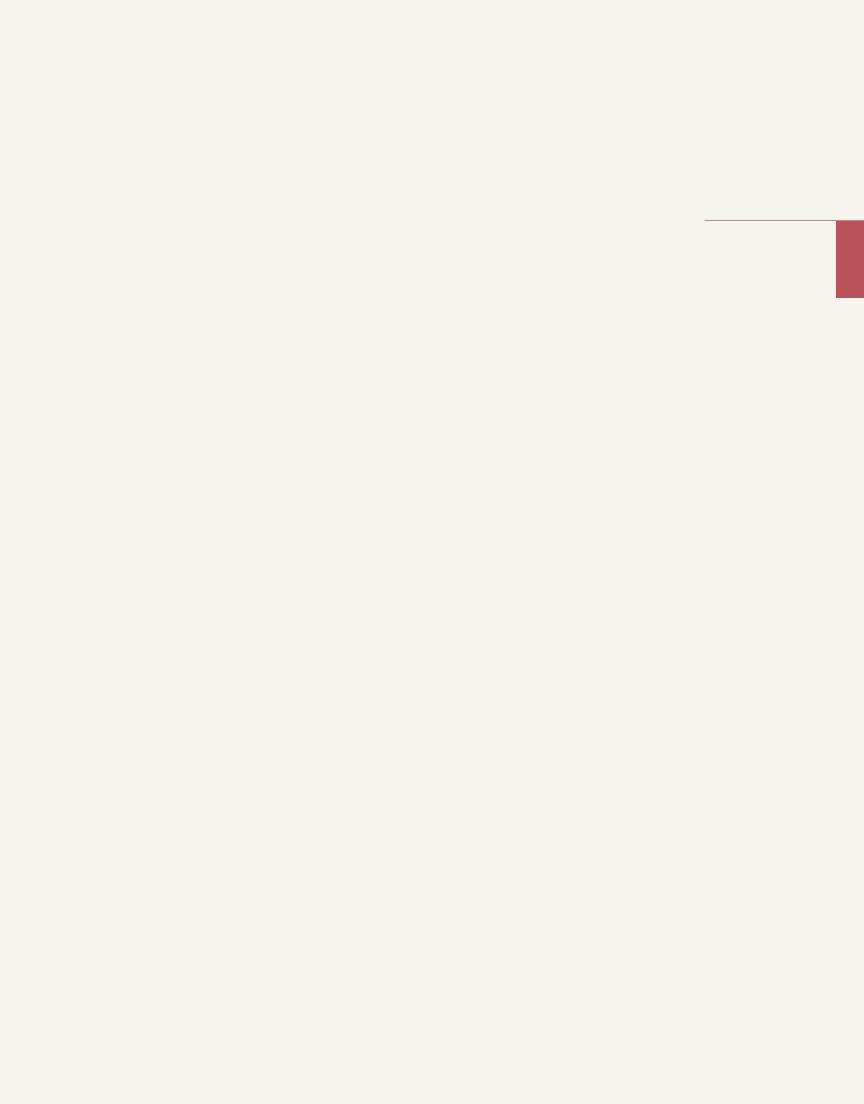

Humankind seems to have originated in Africa in the very remote past. From that great continent also comes the earliest evidence of human recognition of abstract images in the natural environment, if not the first examples of what people generally call “art.” In 1925, explorers of a cave at Makapansgat in

South Africa discovered bones of Australopithecus, a predecessor of modern humans who lived some three million years ago. Associated with the bones was a waterworn reddish-brown jasperite pebble (FIG. 1-2) that bears an uncanny resemblance to a human face. The nearest known source of this variety of ironstone is 20 miles away from the cave. One of the early humans who took refuge in the rock shelter at Makapansgat must have noticed the pebble in a streambed and, awestruck by the “face” on the stone, brought it back for safekeeping.

Is the Makapansgat pebble art? In modern times, many artists have created works people universally consider art by removing objects from their normal contexts, altering them, and then labeling them. In 1917, for example, Marcel Duchamp took a ceramic urinal, set it on its side, called it Fountain (FIG. 24-27), and declared his “ready-made” worthy of exhibition among more conventional artworks. But the artistic environment of the past century cannot be projected into the remote past. For art historians to declare a found object such as the Makapansgat pebble an “artwork,” it must have been modified by human intervention beyond mere selection—and it was not. In fact, evidence indicates that, with few exceptions, it was not until three million years later, around 30,000 BCE, when large parts of northern Europe were still covered with glaciers during the Ice Age, that humans intentionally manufactured sculptures and paintings. That is when the story of art through the ages really begins.

PALEOLITHIC ART

The several millennia following 30,000 BCE saw a powerful outburst of creativity. The works produced by the peoples of the Old Stone Age or Paleolithic period (from the Greek paleo, “old,” and lithos, “stone”) are of an astonishing variety. They range from simple shell necklaces to human and animal forms in ivory, clay, and stone to monumental paintings, engravings, and relief sculptures covering the huge wall surfaces of caves. During the Paleolithic period, humankind went beyond the recognition of human and animal

1 in.

1-2 Waterworn pebble resembling a human face, from Makapansgat,

South Africa, ca. 3,000,000 BCE. Reddish-brown jasperite, 2 – wide.

3

8

Three million years ago someone recognized a face in this pebble and brought it to a rock shelter for safekeeping, but the stone is not an artwork because it was neither manufactured nor modified.

forms in the natural environment to the representation (literally, the presenting again—in different and substitute form—of something observed) of humans and animals. The immensity of this achievement cannot be exaggerated.

Africa

Some of the earliest paintings yet discovered come from Africa, and, like the treasured pebble in the form of a face found at Makapansgat, the oldest African paintings were portable objects.

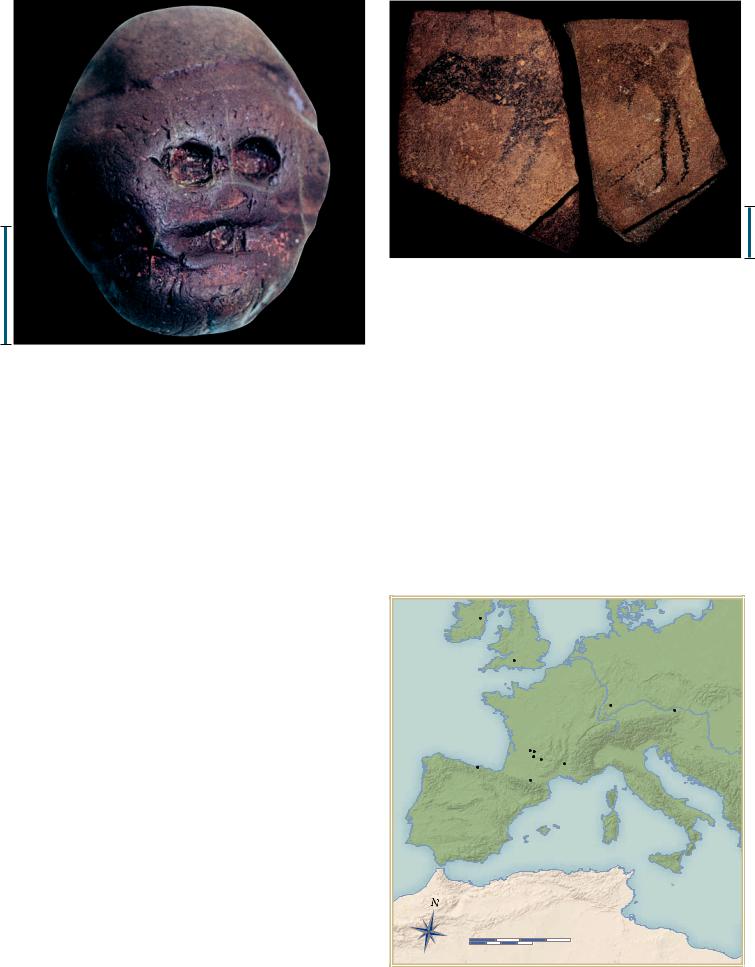

APOLLO 11 CAVE Between 1969 and 1972, scientists working in the Apollo 11 Cave in Namibia found seven fragments of stone plaques with paint on them, including four or five recognizable images of animals. In most cases, including the example illustrated here (FIG. 1-3), the species is uncertain, but the forms are always carefully rendered. One plaque depicts a striped beast, possibly a zebra. The charcoal from the archaeological layer in which the Namibian plaques were found has been dated to around 23,000 BCE.

Like every artist in every age in every medium, the painter of the Apollo 11 plaque had to answer two questions before beginning work: What shall be my subject? How shall I represent it? In Paleolithic art, the almost universal answer to the first question was an animal—bison, mammoth, ibex, and horse were most common. In fact, Paleolithic painters and sculptors depicted humans infrequently and men almost never. In equally stark contrast to today’s world, there was also agreement on the best answer to the second question. Artists presented virtually every animal in every Paleolithic, Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age), and Neolithic (New Stone Age) painting in the same manner—in strict profile. The profile is the only view of an animal wherein the head, body, tail, and all four legs can be seen. A frontal view would have concealed most of the body, and a three-quarter view would not have shown either the front or side fully. Only the profile view is completely informative about the animal’s shape, and this is why the Stone Age painter chose it. A very long time passed before artists placed any pre-

1 in.

1-3 Animal facing left, from the Apollo 11 Cave, Namibia, ca. 23,000 BCE.

Charcoal on stone, 5 4 – . State Museum of Namibia, Windhoek.

1

4

Like most other paintings for thousands of years, this very early example from Africa represents an animal in strict profile so that the head, body, tail, and all four legs are clearly visible.

mium on “variety” or “originality,” either in subject choice or in representational manner. These are quite modern notions in the history of art. The aim of the earliest painters was to create a convincing image of the subject, a kind of pictorial definition of the animal capturing its very essence, and only the profile view met their needs.

Western Europe

Even older than the Namibian painted plaques are some of the first sculptures and paintings of western Europe (MAP 1-1), although examples of still greater antiquity may yet be found in Africa, bridging the gap between the Makapansgat pebble and the Apollo 11 painted plaques.

Newgrange |

North |

|

|

I R E L A N D |

Sea |

|

|

E N G L A N D |

|

|

|

Stonehenge |

|

|

|

|

|

G E R M A N Y |

|

ATLANTIC |

|

Hohlenstein- |

|

OCEAN |

|

Stadel |

Willendorf |

|

F R A N C E |

A U S T R I A |

|

La Madeleine |

Lascaux |

|

|

Laussel |

Pech-Merle |

|

|

Vallon- |

|

|

|

Altamira |

|

|

|

|

Pont-d’Arc |

|

|

Le Tuc d’Audoubert |

I T A L Y |

|

|

S P A I N

Mediterranean Sea

M A L T A

M A L T A

A F R I C A

0 |

250 |

500 miles |

0 |

250 |

500 kilometers |

MAP 1-1 Prehistoric sites in Europe.

2 Chapter 1 A RT B E F O R E H I S TO RY

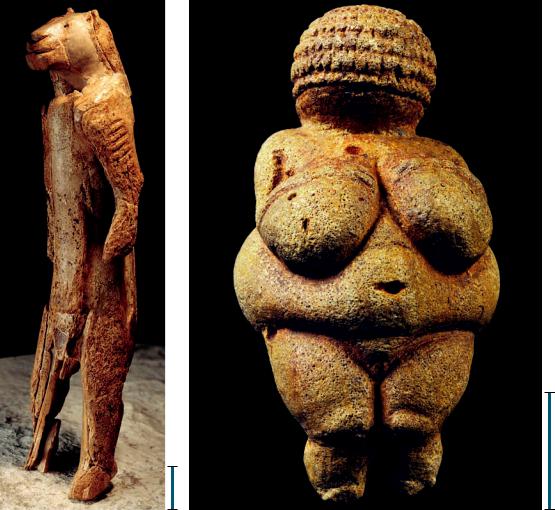

1-4 Human with feline head, from Hohlenstein-Stadel, Germany, ca. 30,000–28,000 BCE.

Mammoth ivory, 11 – high.

5

8

Ulmer Museum, Ulm.

One of the oldest known sculptures is this large ivory figure of a human with a feline head. It is uncertain whether the work

depicts a composite creature or a human wearing an animal mask.

HOHLENSTEIN-STADEL

One of the earliest sculptures discovered yet is an extraordinary ivory statuette (FIG. 1-4), which may date back as far as 30,000 BCE. It was found in fragments inside a cave at Hohlen- stein-Stadel in Germany and

has been meticulously restored. Carved out of mammoth ivory and nearly a foot tall—a truly huge image for its era—the statuette represents something that existed only in the vivid imagination of the unknown sculptor who conceived it. It is a human (whether male or female is debated) with a feline head. Such composite creatures with animal heads and human bodies (and vice versa) were common in the art of the ancient Near East and Egypt (compare, for example, FIGS. 2-10, right, and 3-36). In those civilizations, surviving texts usually allow historians to name the figures and describe their role in contemporary religion and mythology. But for Stone Age representations, no one knows what their makers had in mind. The animalheaded humans of Paleolithic art sometimes have been called sorcerers and described as magicians wearing masks. Similarly, Paleolithic human-headed animals have been interpreted as humans dressed up as animals. In the absence of any Stone Age written explanations— this is a time before writing, before (or pre-) history—researchers can only speculate on the purpose and function of a statuette such as that from Hohlenstein-Stadel.

Art historians are certain, however, that these statuettes were important to those who created them, because manufacturing an ivory figure, especially one a foot tall, was a complicated process. First, a tusk had to be removed from the dead animal by cutting into the ivory where it joined the head. The sculptor then cut the tusk to the desired size and rubbed it into its approximate final shape with sandstone. Finally, a sharp stone blade was used to carve the body, limbs, and head, and a stone burin (a pointed engraving tool) to incise (scratch) lines into the surfaces, as on the Hohlenstein-Stadel creature’s arms. All this probably required at least several days of skilled work.

1 in.

1 in.

1-5 Nude woman (Venus of Willendorf ), from Willendorf, Austria,

ca. 28,000–25,000 BCE. Limestone, 4 – high. Naturhistorisches

1

4

Museum,Vienna.

The anatomical exaggerations in this tiny figurine from Willendorf are typical of Paleolithic representations of women, whose child-bearing capabilities ensured the survival of the species.

VENUS OF WILLENDORF The composite feline-human from Germany is exceptional for the Stone Age. The vast majority of prehistoric sculptures depict either animals or humans. In the earliest art, humankind consists almost exclusively of women as opposed to men, and the painters and sculptors almost invariably showed them nude, although scholars generally assume that during the Ice Age both women and men wore garments covering parts of their bodies. When archaeologists first discovered Paleolithic statuettes of women, they dubbed them “Venuses,” after the Greco-Roman goddess of beauty and love, whom artists usually depicted nude (FIG. 5-62). The nickname is inappropriate and misleading. It is doubtful that the Old Stone Age figurines represented deities of any kind.

One of the oldest and the most famous of the prehistoric female figures is the tiny limestone figurine of a woman that long has been known as the Venus of Willendorf (FIG. 1-5) after its findspot in Austria. Its cluster of almost ball-like shapes is unusual, the result in part of the sculptor’s response to the natural shape of the stone selected for carving. The anatomical exaggeration has suggested to many that this and similar statuettes served as fertility images. But other Paleolithic stone women of far more slender proportions exist, and the meaning of these images is as elusive as everything else about Paleolithic

Paleolithic Art |

3 |

art. Yet the preponderance of female over male figures in the Old Stone Age seems to indicate a preoccupation with women, whose child-bearing capabilities ensured the survival of the species.

One thing at least is clear. The Venus of Willendorf sculptor did not aim for naturalism in shape and proportion. As with most Paleolithic figures, the sculptor did not carve any facial features. Here the carver suggested only a mass of curly hair or, as some researchers have recently argued, a hat woven from plant fibers—evi- dence for the art of textile manufacture at a very early date. In either case, the emphasis is on female anatomy. The breasts of the Willendorf woman are enormous, far larger than the tiny forearms and hands that rest upon them. The carver also took pains to scratch into the stone the outline of the pubic triangle. Sculptors often omitted this detail in other early figurines, leading some scholars to question the nature of these figures as fertility images. Whatever the purpose of these statuettes, the makers’ intent seems to have been to represent not a specific woman but the female form.

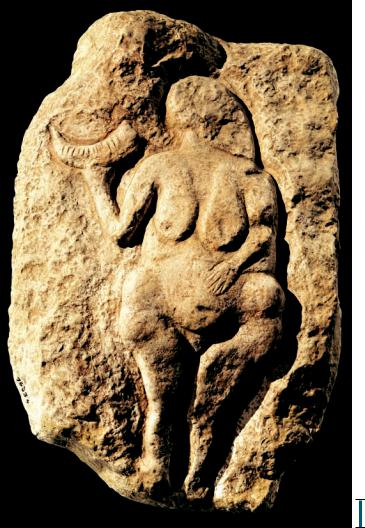

LAUSSEL Because precision in dating is impossible for the Paleolithic era, art historians usually can be no more specific than assigning a range of several thousand years to each artifact. But probably later in date than the Venus of Willendorf is a female figure (FIG. 1-6) from Laussel in France. The Willendorf and Hohlenstein-Stadel figures were sculpted in the round (that is, they are freestanding sculptures). The Laussel woman is one of the earliest relief sculptures known. The sculptor employed a stone chisel to cut into the relatively flat surface of a large rock and create an image that projects from its background.

Today the Laussel relief is exhibited in a museum, divorced from its original context, a detached piece of what once was a much more imposing monument. When the relief was discovered, the

1

Laussel woman (who is about 1– feet tall, more than four times

2

larger than the Willendorf statuette) was part of a great stone block that measured about 140 cubic feet. The carved block stood in the open air in front of a Paleolithic rock shelter. Rock shelters were a common type of dwelling for early humans, along with huts and the mouths of caves. The Laussel relief is one of many examples of open-air art in the Old Stone Age. The popular notions that early humans dwelled exclusively in caves and that all Paleolithic art comes from mysterious dark caverns are false.

After chiseling out the female form and incising the details with a sharp burin, the Laussel sculptor applied red ocher, a naturally colored mineral, to the body. (The same color is also preserved on parts of the Venus of Willendorf.) Contrary to modern misconceptions about ancient art, stone sculptures were frequently painted in antiquity. The Laussel woman has the same bulbous forms as the earlier Willendorf figurine, with a similar exaggeration of the breasts, abdomen, and hips. The head is once again featureless, but the arms have taken on greater importance. The left arm draws attention to the midsection and pubic area, and the raised right hand holds what most scholars identify as a bison horn. The meaning of the horn is debated.

LE TUC D’AUDOUBERT Paleolithic sculptors sometimes created reliefs by building up forms out of clay rather than by cutting into stone blocks or stone walls. Sometime 12,000 to 17,000 years ago in the low-ceilinged circular space at the end of a succession of cave chambers at Le Tuc d’Audoubert, a master sculptor modeled a pair of bison (FIG. 1-7) in clay against a large, irregular freestanding rock. The two bison, like the much older painted animal (FIG. 1-3) from the Apollo 11 Cave, are in strict profile. Each is about two feet long. They are among the largest Paleolithic sculptures known. The sculptor brought the clay from elsewhere in the cave complex and modeled it by hand into the overall shape of the animals. The artist then

4 Chapter 1 A RT B E F O R E H I S TO RY

1 in.

1-6 Woman holding a bison horn, from Laussel, France, ca. 25,000– 20,000 BCE. Painted limestone, 1 6 high. Musée d’Aquitaine, Bordeaux.

One of the oldest known relief sculptures depicts a woman who holds a bison horn and whose left arm draws attention to her belly. Scholars continue to debate the meaning of the gesture and the horn.

smoothed the surfaces with a spatula-like tool and finally used fingers to shape the eyes, nostrils, mouths, and manes. The cracks in the two animals resulted from the drying process and probably appeared within days of the sculptures’ completion.

LA MADELEINE As already noted, sculptors fashioned ivory mammoth tusks into human and animal (FIG. 1-4) forms from very early times. Prehistoric carvers also used antlers as a sculptural medium, even though it meant they were forced to work on a very small scale. The broken spearthrower (FIG. 1-8) in the form of a bison found at La Madeleine in France is only four inches long and was carved from reindeer antler. The sculptor incised lines into the bison’s mane using a sharp burin. Compared to the bison at Le Tuc d’Audoubert, the engraving is much more detailed and extends to the horns, eye, ear, nostrils, mouth, and the hair on the face. Especially interesting is the engraver’s decision to represent the bison with the head turned. The small size of the reindeer horn may have been the motivation for this space-saving device. Whatever the reason, it is noteworthy that the sculptor turned the neck a full 180 degrees to maintain the strict profile Paleolithic sculptors and painters insisted on for the sake of clarity and completeness.

ALTAMIRA The works examined here thus far, whether portable or fixed to rocky outcroppings or cave walls, are all small. They are dwarfed by the “herds” of painted animals that roam the cave walls of southern France and northern Spain, where some of the most spectacular prehistoric art has been discovered (see “Paleolithic Cave Painting,” page 6). The first examples of cave paintings were found accidentally by an amateur archaeologist in 1879 at Altamira, Spain. Don Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was exploring a cave where he had already found specimens of flint and carved bone. His little daughter Maria was with him when they reached a chamber some 85 feet from the cave’s entrance. Because it was dark and the ceiling of the debrisfilled cavern was only a few inches above the father’s head, the child was the first to discern, from her lower vantage point, the shadowy forms of painted beasts on the cave roof (FIG. 1-9, a detail of a much

1 in.

1-7 Two bison, reliefs in a cave at Le Tuc d’Audoubert, France, ca. 15,000–10,000 BCE. Clay, each 2 long.

Representations of animals are far more common than of humans in Paleolithic European art. The sculptor

built up these clay bison using a stone spatula-like smoothing tool and fingers to shape the details.

1 ft.

1 ft.

1-8 Bison with turned head, fragmentary spearthrower, from La Madeleine, France, ca. 12,000 BCE. Reindeer horn, 4 long.

This fragment of a spearthrower was carved from reindeer antler. Details were incised with a stone burin. The sculptor turned the bison’s head a full 180 degrees to maintain the profile view.

1-9 Bison, detail of a painted ceiling in the cave at Altamira, Spain, ca. 12,000–11,000 BCE. Each bison 5 long.

As in other Paleolithic caves, the painted ceiling at Altamira has

no ground line or indication of setting. The artist’s sole concern was representing the animals, not locating them in a specific place.

Paleolithic Art |

5 |

M A T E R I A L S A N D T E C H N I Q U E S

Paleolithic Cave Painting

The caves of Altamira (FIG. 1-9), Pech-Merle (FIG. 1-10), Lascaux (FIGS. 1-11 and 1-13), and other sites in prehistoric Europe are a few hundred to several thousand feet long. They are often choked,

sometimes almost impassably, by deposits, such as stalactites and stalagmites. Far inside these caverns, well removed from the cave mouths early humans often chose for habitation, painters sometimes made pictures on the walls. Examples of Paleolithic painting now have been found at more than 200 sites, but prehistorians still regard painted caves as rare occurrences, because the images in them, even if they number in the hundreds, were created over a period of some 10,000 to 20,000 years.

To illuminate the surfaces while working, the Paleolithic painters used stone lamps filled with marrow or fat, with a wick, perhaps, of moss. For drawing, they used chunks of red and yellow ocher. For painting, they ground these same ochers into powders they mixed with water before applying. Recent analyses of the pigments used show that Paleolithic painters employed many different minerals, attesting to a technical sophistication surprising at so early a date.

Large flat stones served as palettes. The painters made brushes from reeds, bristles, or twigs, and may

1-10 Spotted horses and negative hand imprints, wall painting in the cave at Pech-Merle, France, ca. 22,000 BCE. 11 2 long.

The purpose and meaning of Paleolithic art are unknown. Some researchers think the painted hands near the PechMerle horses are “signatures” of community members or of individual painters.

have used a blowpipe of reeds or hollow bones to spray pigments on out-of-reach surfaces. Some caves have natural ledges on the rock walls upon which the painters could have stood in order to reach the upper surfaces of the naturally formed chambers and corridors. One Lascaux gallery has holes in one of the walls that once probably anchored a scaffold made of saplings lashed together. Despite the difficulty of making the tools and pigments, modern attempts at replicating the techniques of Paleolithic painting have demonstrated that skilled workers could cover large surfaces with images in less than a day.

1 ft.

larger painting approximately 60 feet long). Sanz de Sautuola was certain the bison painted on the ceiling of the cave on his estate dated back to prehistoric times. Professional archaeologists, however, doubted the authenticity of these works, and at the Lisbon Congress on Prehistoric Archaeology in 1880, they officially dismissed the paintings as forgeries. But by the close of the century, other caves had been discovered with painted walls partially covered by mineral deposits that would have taken thousands of years to accumulate. This finally persuaded skeptics that the first paintings were of an age far more remote than they had ever dreamed.

The bison at Altamira are 13,000 to 14,000 years old, but the painters of Paleolithic Spain approached the problem of representing an animal in essentially the same way as the painter of the Namibian stone plaque (FIG. 1-3), who worked in Africa more than 10,000 years earlier. Every one of the Altamira bison is in profile, whether alive and standing or curled up on the ground (probably dead, although this is disputed; one suggestion is that these bison are giving birth). To maintain the profile in the latter case, the painter had to adopt a viewpoint above the animal, looking down, rather than the view a person standing on the ground would have.

Modern critics often refer to the Altamira animals as a “group” of bison, but that is very likely a misnomer. In FIG. 1-9, the several

bison do not stand on a common ground line (a painted or carved baseline on which figures appear to stand in paintings and reliefs), nor do they share a common orientation. They seem almost to float above viewers’ heads, like clouds in the sky. And the dead(?) bison are seen in an “aerial view,” while the others are seen from a position on the ground. The painting has no setting, no background, no indication of place. The Paleolithic painter was not at all concerned with where the animals were or with how they related to one another, if at all. Instead, several separate images of a bison adorn the ceiling, perhaps painted at different times, and each is as complete and informative as possible—even if their meaning remains a mystery (see “Art in the Old Stone Age,” page 7).

PECH-MERLE That the paintings did have meaning to the Paleolithic peoples who made and observed them cannot, however, be doubted. In fact, signs consisting of checks, dots, squares, or other arrangements of lines often accompany the pictures of animals. Representations of human hands also are common. At Pech-Merle in France, painted hands accompany representations of spotted horses (FIG. 1-10). These and the majority of painted hands at other sites are “negative;” that is, the painter placed one hand against the wall and then brushed or blew or spat pigment around it. Occasionally,

6 Chapter 1 A RT B E F O R E H I S TO RY

A R T A N D S O C I E T Y

Art in the Old Stone Age

From the moment in 1879 that cave paintings were discovered at Altamira (FIG. 1-9), scholars have wondered why the hunters of the Old Stone Age decided to cover the walls of dark caverns with

animal images like those found at Altamira, Pech-Merle (FIG. 1-10), Lascaux (FIGS. 1-11 and 1-13), and Vallon-Pont-d’Arc (FIG. 1-12). Scholars have proposed various theories including that the painted and engraved animals were mere decoration, but this explanation cannot account for the narrow range of subjects or the inaccessibility of many of the representations. In fact, the remoteness and difficulty of access of many of the images, and indications that the caves were used for centuries, are precisely why many researchers have suggested that the prehistoric hunters attributed magical properties to the images they painted and sculpted. According to this argument, by confining animals to the surfaces of their cave walls, the Paleolithic hunters believed they were bringing the beasts under their control. Some prehistorians have even hypothesized that rituals or dances were performed in front of the images and that these rites served to improve the hunters’ luck. Still others have stated that the animal representations may have served as teaching tools to instruct new hunters about the character of the various species they would encounter or even to serve as targets for spears.

In contrast, some scholars have argued that the magical purpose of the paintings and reliefs was not to facilitate the destruction of bison and other species. Instead, they believe prehistoric painters and sculptors created animal images to assure the survival of the herds on which Paleolithic peoples depended for their food supply and for their clothing. A central problem for both the hunting-magic and food-creation theories is that the animals that seem to have been diet staples of Old Stone Age peoples are not those most frequently portrayed. For example, faunal remains show that the Altamirans ate red deer, not bison.

Other scholars have sought to reconstruct an elaborate mythology based on the cave paintings and sculptures, suggesting that Paleolithic humans believed they had animal ancestors. Still others have equated certain species with men and others with women and postulated various meanings for the abstract signs that sometimes accompany the images. Almost all of these theories have been discredited over time, and most prehistorians admit that no one knows the intent of these representations. In fact, a single explanation for all Paleolithic animal images, even ones similar in subject, style, and composition (how the motifs are arranged on the surface), is unlikely to apply universally. The works remain an enigma—and always will, because before the invention of writing, no contemporaneous explanations could be recorded.

1 ft.

1-11 Hall of the Bulls (left wall) in the cave at Lascaux, France, ca. 15,000–13,000 BCE. Largest bull 11 6 long.

Several species of animals appear together in the Hall of the Bulls. Many are colored silhouettes, but others were created by outline alone—the two basic approaches to painting in the history of art.

Paleolithic Art |

7 |

M A T E R I A L S A N D T E C H N I Q U E S

The World’s Oldest Paintings?

One of the most spectacular archaeological finds of the past century came to light in December 1994 at Vallon-Pont- d’Arc, France, and was announced at a press conference in Paris on January 18, 1995. Unlike some other recent “finds” of prehistoric art that proved to be forgeries, the paintings in the Chauvet Cave (named after the leader of the exploration team, Jean-Marie Chauvet) seemed to be authentic. But no one, including Chauvet and his colleagues, guessed at the time of their discovery that radiocarbon dating (a measure of the rate of degeneration of carbon 14 in organic materials) of the paintings might establish that the murals in the cave were more than 15,000 years older than those at Altamira (FIG. 1-9). When the scientific tests were completed, the French archaeologists announced that the Chauvet Cave paintings were the

oldest yet found anywhere, datable around 30,000–28,000 BCE.

This new early date immediately caused scholars to reevaluate the scheme of “stylistic development” from simple to more complex forms that had been nearly universally accepted for decades. In the Chauvet Cave, in contrast to Lascaux (FIG. 1-11), the horns of the aurochs (extinct long-horned wild oxen) are shown naturalistically,

1-12 Aurochs, horses, and rhinoceroses, wall painting in the Chauvet Cave, Vallon-Pont-d’Arc, France, ca. 30,000–28,000 or

ca. 15,000–13,000 BCE.

The date of the Chauvet Cave paintings is the subject of much controversy. If the murals are the oldest paintings known, they exhibit surprisingly advanced features, such as overlapping animal horns.

one behind the other, not in the twisted perspective thought to be universally characteristic of Paleolithic art. Moreover, the two rhinoceroses at the lower right of FIG. 1-12 appear to confront each other, suggesting to some observers that the artist intended a narrative, another “first” in either painting or sculpture. If the paintings are twice as old as those of Lascaux, Altamira (FIG. 1-9), and PechMerle (FIG. 1-10), the assumption that Paleolithic art “evolved” from simple to more sophisticated representations is wrong.

Much research remains to be conducted in the Chauvet Cave, but already the paintings have become the subject of intense controversy. Recently, some archaeologists have contested the early dating of the Chauvet paintings on the grounds that the tested samples were contaminated. If the Chauvet animals were painted later than those at Lascaux, their advanced stylistic features can be more easily explained. The dispute exemplifies the frustration—and the excite- ment—of studying the art of an age so remote that almost nothing remains and almost every new find causes art historians to reevaluate what had previously been taken for granted.

1 ft.

the painter dipped a hand in the pigment and then pressed it against the wall, leaving a “positive” imprint. These handprints, too, must have had a purpose. Some researchers have considered them “signatures” of cult or community members or, less likely, of individual painters. But like everything else in Paleolithic art, their meaning is unknown.

The mural (wall) paintings at Pech-Merle also allow some insight into the reason certain subjects may have been chosen for a specific location. One of the horses (at the right in FIG. 1-10) may have been inspired by the rock formation in the wall surface resembling a horse’s head and neck. Old Stone Age painters and sculptors

8 Chapter 1 A RT B E F O R E H I S TO RY

frequently and skillfully used the caves’ naturally irregular surfaces to help give the illusion of real presence to their forms. Many of the Altamira bison (FIG. 1-9), for example, were painted over bulging rock surfaces. In fact, prehistorians have observed that bison and cattle appear almost exclusively on convex surfaces, whereas nearly all horses and hands are painted on concave surfaces. What this signifies has yet to be determined.

LASCAUX Perhaps the best-known Paleolithic cave is that at Lascaux, near Montignac, France. It is extensively decorated, but most of the paintings are hundreds of feet from any entrance, far removed

from the daylight. The largest painted area at Lascaux is the so-called Hall of the Bulls (FIG. 1-11), although not all of the animals depicted are bulls. Many are represented using colored silhouettes, as at Altamira (FIG. 1-9) and on the Apollo 11 plaque (FIG. 1-3). Others— such as the great bull at the right in FIG. 1-11—were created by outline alone, as were the Pech-Merle horses (FIG. 1-10). On the walls of the Lascaux cave one sees, side by side, the two basic approaches to drawing and painting found repeatedly in the history of art. These differences in style and technique alone suggest that the animals in the Hall of the Bulls were painted at different times, and the modern impression of a rapidly moving herd of beasts was probably not the original intent. In any case, the “herd” consists of several different kinds of animals of various sizes moving in different directions.

Another feature of the Lascaux paintings deserves attention. The bulls there show a convention of representing horns that has been called twisted perspective or a composite view, because viewers see the heads in profile but the horns from the front. Thus, the painter’s approach is not strictly or consistently optical (seen from a fixed viewpoint). Rather, the approach is descriptive of the fact that cattle have two horns. Two horns are part of the concept “bull.” In strict opticalperspective profile, only one horn would be visible, but to paint the animal in that way would amount to an incomplete definition of it. This kind of twisted perspective was the norm in prehistoric painting, but it was not universal. In fact, the recent discovery at Vallon-Pont-d’Arc in France of Paleolithic paintings (FIG. 1-12) in the Chauvet Cave, where the painters represented horns in a more natural way, has caused art historians to rethink many of the assumptions they had made about Paleolithic art (see “The World’s Oldest Paintings?” page 8).

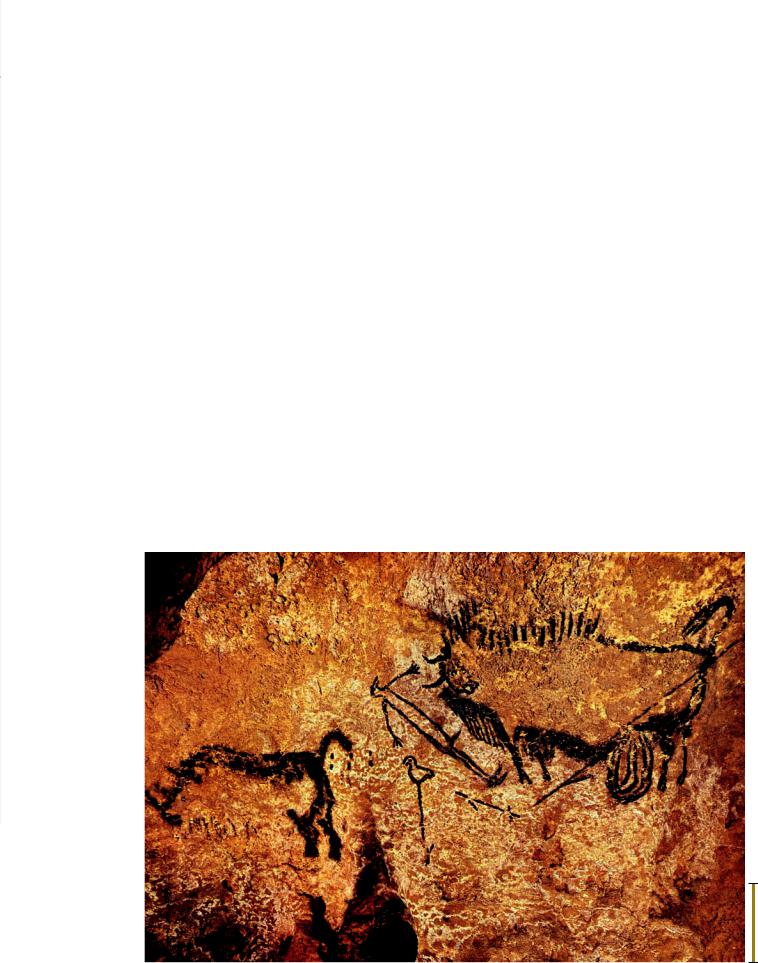

Perhaps the most perplexing painting (FIG. 1-13) in the Paleolithic caves of Europe is deep in a well shaft at Lascaux, where man (as opposed to woman) makes one of his earliest appearances in prehistoric art. At the left, and moving to the left, is a rhinoceros, rendered with all the skilled attention to animal detail customarily seen in cave art. Beneath its tail are two rows of three dots of uncertain significance. At the right is a bison, also facing left but more schematically painted, probably by someone else. The second painter nonetheless successfully suggested the bristling rage of the animal, whose bowels are hanging from it in a heavy coil. Between the two beasts is a bird-faced (masked?) man (compare the feline-headed human, FIG. 1-4, from HohlensteinStadel) with outstretched arms and hands with only four fingers. The man is depicted with far less care and detail than either animal, but the painter made the hunter’s gender explicit by the prominent penis. The position of the man is ambiguous. Is he wounded or dead or merely tilted back and unharmed? Do the staff(?) with the bird on top and the spear belong to him? Is it he or the rhinoceros who has gravely wounded the bison—or neither? Which animal, if either, has knocked the man down, if indeed he is on the ground? Are these three images related at all? Researchers can be sure of nothing, but if the painter placed the figures beside each other to tell a story, then this is evidence for the creation of complex narrative compositions involving humans and animals at a much earlier date than anyone had imagined only a few generations ago. Yet it is important to remember that even if the artist intended to tell a story, very few people would have been able to “read” it. The painting, in a deep shaft, is very difficult to reach and could have been viewed only in flickering lamplight. Like all Paleolithic art, the scene in the Lascaux well shaft remains enigmatic.

1 ft.

1-13 Rhinoceros, wounded man, and disemboweled bison, painting in the well of the cave at Lascaux, France, ca. 15,000–13,000 BCE. Bison 3 8 long.

If these paintings of two animals and a bird-faced (masked?) man deep in a Lascaux well shaft depict a hunting scene, they constitute the earliest example of narrative art ever discovered.

Paleolithic Art |

9 |

NEOLITHIC ART

Around 9000 BCE, the ice that covered much of northern Europe during the Paleolithic period melted as the climate grew warmer. The sea level rose more than 300 feet, separating England from continental Europe and Spain from Africa. The reindeer migrated north, and the woolly mammoth disappeared. The Paleolithic gave way to a transitional period, the Mesolithic, and then, for several thousand years at different times in different parts of the globe, a great new age, the Neolithic, dawned. Human beings began to domesticate plants and animals and to settle in fixed abodes. Their food supply assured, many groups changed from hunters to herders, to farmers, and finally to townspeople. Wandering hunters settled down to organized community living in villages surrounded by cultivated fields.

The basis for the conventional division of prehistory into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic periods is the development of stone implements. However, a different kind of distinction may be made between an age of food gathering and an age of food production. In this scheme, the Paleolithic period corresponds roughly to the age of food gathering, and the Mesolithic period, the last phase of that age, is marked by intensified food gathering and the taming of the dog. In the Neolithic period, agriculture and stock raising became humankind’s major food sources. The transition to the Neolithic occurred first in the ancient Near East.

Ancient Near East

The remains of the oldest known settled communities have been found in the grassy foothills of the Antilebanon, Taurus, and Zagros mountains in present-day Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and Iran (MAP 1-2). These regions provided the necessary preconditions for the development of agriculture. Species of native plants, such as wild wheat and barley, were plentiful, as were herds of animals (goats, sheep, and pigs) that could be domesticated. Sufficient rain occurred for the raising of crops. When village farming life was well developed, some settlers, attracted by the greater fertility of the soil and perhaps also by the need to find more land for their rapidly growing populations, moved into the valleys and deltas of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

In addition to systematic agriculture, the new sedentary societies of the Neolithic Age originated weaving, metalworking, pottery, and counting and recording with clay tokens. Soon, these innovations spread with remarkable speed throughout the Near East. Village farming communities such as Jarmo in Iraq and Çatal Höyük in southern Anatolia date back to the mid-seventh millennium BCE. The remarkable fortified town of Jericho, before whose walls the biblical Joshua appeared thousands of years later, is even older. Archaeologists are constantly uncovering surprises, and the discovery and exploration of new sites each year are compelling them to revise their views about the emergence of Neolithic society. But three sites known for some time—Jericho, Ain Ghazal, and Çatal Höyük—offer a fascinating picture of the rapid and exciting transformation of human society and of art during the Neolithic period.

JERICHO By 7000 BCE, agriculture was well established from Anatolia to ancient Palestine and Iran. Its advanced state by this date presupposes a long development. Indeed, the very existence of a major settlement such as Jericho gives strong support to this assumption. The site of Jericho—a plateau in the Jordan River valley with a spring that provided a constant water supply—was occupied by a small village as early as the ninth millennium BCE. This village

Black Sea |

Caspian |

|

Sea |

||

|

|

|

T U R K E Y |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Çatal |

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

|

|

||

Hacilar |

|

|

Höyük |

|

|

|

|

n |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

i |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

T |

|

u |

ta |

|

|

|

|

|

|

i |

|||||

|

|

a |

u |

u |

o |

n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

T |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

g |

|||||

|

|

|

M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

r |

s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

E |

|

|

|

i |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

up |

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

hr |

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

t |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

S Y R I A |

|

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mediterranean Sea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

. |

Antilebanon |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

a |

Mountains |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

n |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jericho |

|

d |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

r |

Ain Ghazal |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

J |

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

o |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Z |

I R A N |

|

a |

||

g |

||

|

r |

|

|

o |

|

Jarmo |

s |

|

M |

||

|

||

|

o |

|

|

u |

|

|

n |

|

|

t |

|

|

a |

|

|

i |

|

|

n |

|

|

s |

|

I R A Q

E G Y P T |

Persian |

|

Gulf |

||

|

N |

|

|

|

|

|

i |

Red |

0 |

|

200 |

400 miles |

R |

|

||||

l |

|

|

|

|

|

e |

|

|

|

|

|

. |

Sea |

0 |

200 |

400 kilometers |

|

|

|||||

MAP 1-2 Neolithic sites in Anatolia and the Near East.

underwent spectacular development around 8000 BCE, when the inhabitants built a new Neolithic settlement covering about 10 acres. Its mud-brick houses sat on round or oval stone foundations and had roofs of branches covered with earth.

1-14 Great stone tower built into the settlement wall, Jericho, ca. 8000–7000 BCE.

Neolithic Jericho was protected by 5-foot-thick walls and at least

one stone tower 30 feet high and 33 feet in diameter—an outstanding achievement that marks the beginning of monumental architecture.

10 Chapter 1 A RT B E F O R E H I S TO RY