ICCROM_ICS03_ReligiousHeritage_en

.pdf

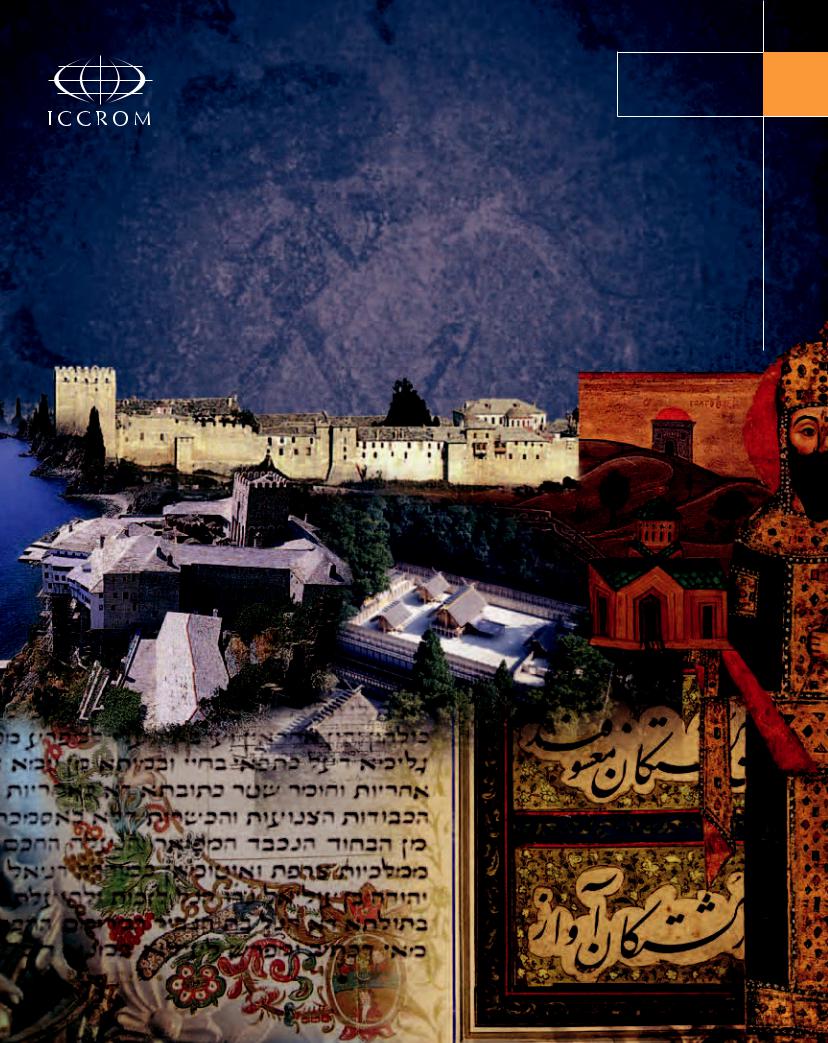

ICCROM 3 COnseRvatIOn

studIes

Conservation of Living

Religious Heritage

ICCROM 3 COnseRvatIOn

studIes

Conservation of Living

Religious Heritage

Papers from the ICCRoM 2003forum on Living Religious Heritage: conserving the sacred

Editors

Herb Stovel, Nicholas Stanley-Price, Robert Killick

ISBN 92-9077-189-5

© 2005 ICCROM

International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele, 13

00153 Rome, Italy

www.iccrom.org

Designed by Maxtudio, Rome

Printed by Ugo Quintily S.p.A.

Contents

Preface |

v |

NICHOLAS StANLey-PRICe |

|

1

2

introduction |

1 |

HeRB StOVeL |

|

|

|

Conserving built heritage in Maori communities |

12 |

DeAN WHItINg |

|

|

|

Christiansfeld: a religious heritage alive and well. |

|

TwenTy-firsT cenTury influences on a laTe eighTeenTh- |

|

early nineTeenTh cenTury Moravian seTTleMenT in DenMark |

19 |

JøRgeN BøytLeR

3

4

the past is in the present

perspecTives in caring for BuDDhisT heriTage siTes in sri lanka |

31 |

gAMINI WIJeSURIyA |

|

the ise shrine and the Gion Festival

case sTuDies on The values anD auThenTiciTy of Japanese |

|

inTangiBle living religious heriTage |

44 |

NOBUkO INABA

A living religious shrine under siege

5 |

The nJelele shrine/king Mzilikazi’s grave anD conflicTing |

|

|

DeManDs on The MaTopo hills area of ziMBaBwe |

58 |

||

|

PAtHISA NyAtHI AND CHIef BIDI NDIWeNI |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the challenges in reconciling the requirements of faith and |

|

|

6 conservation in Mount Athos |

67 |

||

JANIS CHAtzIgOgAS

7Popular worship of the Most Holy trinity of Vallepietra, central italy

The TransforMaTion of TraDiTion anD The safeguarDing |

|

of iMMaTerial culTural heriTage |

74 |

8

9

PAOLA eLISABettA SIMeONI

Conserving religious heritage within communities in Mexico |

86 |

|

VALeRIe MAgAR |

|

|

|

|

|

Collection management of islamic heritage in accordance |

|

|

with the worldview and shari’ah of islam |

94 |

|

AMIR H. zekRgOO AND MANDANA BARkeSHLI

10

11

the conservation of sacred materials in the israel Museum |

102 |

MICHAeL MAggeN |

|

|

|

religious heritage as a meeting point for dialogue |

107 |

The caTheDral workshops experience |

|

CRIStINA CARLO-SteLLA

Contributors |

113 |

iv conservaTion of living religious heriTage

Nicholas Stanley-Price

Director-General

ICCROM

Preface

The ICCROM Forum is designed to promote discussion of key contemporary scientific, technical and ethical issues in heritage conservation. It brings together invited

speakers from different backgrounds to discuss a theme identified by ICCROM as being both topical and important for the better understanding of heritage conservation.

The first ICCROM Forum of a new series was held on 20-22 October 2003, on the theme of ‘Living Religious Heritage: conserving the sacred’. It was held at the Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei in the Palazzo Corsini in Rome. We are grateful to the Academy and especially to its then President, Professor Edoardo Vesentini, for allowing us to use its beautiful premises for the meeting.

The invited participants were leading professionals, scholars and managers with experience of managing ‘Living Religious Heritage’ in different regions of the world and with respect to many of its major faiths and traditions. They were asked to prepare papers in case study form, which were circulated to all participants in advance of the Forum. M. Jean-Louis Luxen (Culture, Heritage and Development International (CHEDI), Brussels, and former Secretary-General of ICOMOS) was invited to give a keynote address on the theme.

The present publication consists of papers submitted to the Forum, extensively edited and revised by the authors and editors. Many of the points made by M. Luxen in his keynote address have been incorporated in the Introduction written by Herb Stovel. In addition to the authors of papers published here, two other speakers made valuable contributions to the Forum as speakers, discussants and authors of pre-circulated papers: Sami M. Angawi (Amar Centre for Architectural Heritage, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) on the theme ‘Concept of universal balance and order: an integrated approach to rehabilitate and maintain traditional architecture in Makka’; and Mons. Ruperto Cruz Santos (Philippine Pontifical College, Rome) who presented a case study of ‘Manila Cathedral: preserving the past, anticipating the future’. The paper on Christiansfeld published here by Jorgen Boytler was presented at the Forum by Jorgen From, Mayor of Christiansfeld, who has been an energetic supporter of the Christiansfeld conservation programme.

I am indebted to Herb Stovel (now Carleton University, Ottawa) for agreeing to take on the organization of the Forum, ably assisted by Britta Rudolff (now University of Mainz), and to both of them for their commitment to ensuring the diversity and challenging nature of the issues discussed at it. Many other members of the ICCROM staff made important contributions in planning and organizing the event, and in participating in its proceedings as chairpersons and discussants. To them and to all contributing authors I am deeply grateful.

preface v

[ Herb Stovel ]

Introduction

The topic chosen for the ICCROM Forum in 2003 was ‘Living Religious Heritage’. Implicitly, this choice suggests that ‘living religious heritage’ may differ from

other forms of heritage in some way, and that therefore its conservation might also be subject to different considerations. In what ways might living religious heritage differ

from cultural heritage in general?

Several of the papers published here address this question. Gamini Wijesuriya suggests that what distinguishes religious heritage from secular heritage is its inherent ‘livingness’, that the religious values carried by a stupa embodying the living Buddha, for example, can only be sustained by ongoing processes of physical renewal of the stupa. In ensuring continuity of forms, in effect, ‘living’ heritage values are being elevated above the more familiar ‘documentary’ or ‘historical’ heritage values. The primary goal of conservation becomes continuity itself, based on processes of renewal that continually ‘revive the cultural meaning, significance… and symbolism attached to heritage’.

In turn, Nobuko Inaba notes that, while ‘living’ may be understood as the opposite of ‘dead’ and refer to a place still in use, alternatively, it may be used to denote the presence of residents in settlements on or near the site. Like Wijesuriya, she suggests that attention to the ‘living’ aspects of religious heritage reflects efforts to go beyond the ‘material-oriented conservation practice of monumental heritage’ and to give attention to ‘human-related/non-material aspects of heritage value and trying to link with the surrounding societies and environments’. She further suggests, more provocatively, that ‘fruit from living heritage can be thought of traditional life before modernization and globalization’.

In fact, all religions have regularly had to confront change and modernity; what is different now is the increasing pace of change, fed by improvements in electronic communication which permit ideas that challenge and undermine religious beliefs to be communicated more quickly, and more widely, than ever before.

The pace of change has undermined the strength of traditional belief systems to maintain their place in secular societies, and has also increased tensions between multicultural societies which may previously have lived in relative harmony. These forces have exacerbated extreme nationalism, and polarized relations between and among religious groups, with heritage authorities seeking - often with insufficient understanding of them - to fossilize or freeze various aspects of heritage in the name of conservation.

Taken to an extreme, cultural heritage may be used as a weapon in furthering the competing claims of various faiths. Places and objects of perceived heritage value to two different faiths may be demolished by the adherents of one faith in order to give ascendancy to the other. Such efforts may result in the preservation or reconstruction of buildings selected to reflect favoured versions of history. Jean-Louis Luxen noted in his introductory remarks on the occasion of the forum that ‘religious

introduction 1

conviction contributes to the social cohesion of a community, giving it landmarks and self-confidence… but that…the risk of excessive and chauvinistic assertion of identity, fed by fundamentalism, may lead to the destruction of religious symbols’.

If, as it seems, living religious heritage does have characteristics that distinguish it from other forms of heritage, how might its conservation also differ?

The effectiveness of conservation treatments depends on our ability to define clearly heritage values and to design treatments around respect for the values. Gamini Wijesuriya stresses the differences between ‘religious heritage’ and ‘heritage’ by noting that religious heritage has been born with its values in place, while with other forms of heritage, we need time and distance to be able to ascribe values to heritage (p. 31). These differences will cause the conservator to ask different questions in defining heritage values in the two different situations: for religious heritage, what values are already recognized by the religious community? For secular heritage, what process (involving whom?) will be needed to define these values?

Nobuko Inaba further reminds us to focus on more than typological differences among heritage properties in trying to improve care for religious heritage. She argues that we ought to treat religious properties in a holistic manner, recognizing them ‘as a total expression of their host culture, combining tangible (both immovable and movable) and intangible expressions of heritage together with the natural/cultural landscape’ (p. 44). She notes that in many cases, clear typological distinctions are neither possible nor useful, recognizing that religious forces are based on belief systems which have been at ‘the core of our life’, and noting that ‘any form of living heritage is inseparable from the frameworks of the religion or belief system of its society’.

Other factors are important in trying to define appropriate care for heritage. As several authors note, religious heritage is perhaps the largest single category of heritage property to be found in most countries around the world. Paradoxically, though, it is difficult – in a conservation world where charters are commonplace – to find the kinds of modern rules or doctrinal texts that have so frequently been developed for other aspects of heritage. In fact, in several jurisdictions, religious property is specifically exempted from legislation concerning heritage. But why the relative lack of guidelines and charters? This may be due to a perception in the conservation world that responsibility for religious heritage rests with the religious community or that the religious context is too sensitive for conservation professionals to treat with objectivity and fairness; or it may be due simply to a lack of systematic attention to this type of heritage.

Where there has arisen a proposal to prepare doctrinal texts, as Janis Chatzigogas notes with respect to the monasteries of Mount Athos, this has hitherto consisted of efforts to encourage the resident monks themselves to debate a possible conservation charter. Hence, a general caution is strongly evident among conservation professionals with regard to efforts to define general rules or prescriptions which would reconcile the demands of faith with conservation goals.

A different approach to defining a role for conservation professionals was suggested by JeanLouis Luxen in querying the tension between the singular and the universal. He noted that some religious properties may have universal appeal or outlook and some a kind of singular appeal. He was referring to those properties linked to single communities, or even those where particular taboos

2Conservation of Living Religious Heritage

inhibit the sharing of knowledge and understanding with those outside the faith. In Luxen’s view, that tension is best addressed through following UNESCO’s goal of instituting dialogues among cultures by ‘promoting shared knowledge and reciprocal esteem that contribute towards peace among peoples’.

In summary, it is clear that encouraging dialogue among those involved rather than following prescriptive codes of practice offers a more positive role to conservation professionals to play with regard to living religious heritage. By defining both the needs of the religious community and those of the conservation world, conservation professionals can help to identify options for reconciling needs, to define good practice, and ultimately to build confidence and trust among all partners. The goal of the ICCROM Forum has been to bring together cases where this has been achieved or where the potential for it evidently exists.

Issues In reconciling faith and conservation

The primary challenge addressed by the forum was the reconciliation of faith and conservation requirements. In introducing the forum theme, the author identified six different contexts of interaction between the two:

Dealing with changing liturgical and functional needs

Changes in liturgy or the practice of worship may result in the need to alter the layouts of religious buildings, to move altars or to change the focus of symbolic ceremonies. Equally, changing functional needs (improving the comfort of worshippers in cold or hot climates, for example) can place daunting demands on historic structures and spaces that have long enjoyed a climate equilibrium.

The question for the forum to address was: how to maintain heritage values in the face of changing needs of religious practice?

Dealing with the competing requirements of co-existing faiths

Reconciling faith with conservation is difficult when there are two or more faiths which hold sacred a particular property but which cannot reconcile their own beliefs. Perhaps the most dramatic recent example is the destruction by the Muslim Taliban of the two Buddha figures at Bamiyan in Afghanistan, effected only two years after a decree for the protection of all cultural heritage (including Bamiyan) had been published by the Taliban. The destruction by Hindus of a sixteenth century mosque at Ayodhya in India provides another dramatic example, with both religious groups making claims based on mutually exclusive interpretations of the archaeological evidence from the site. The Haram al-Sharif (or Temple Mount) in Jerusalem remains a flashpoint for conflict among Jewish, Muslim and Christian communities, leading to periodic violent confrontations and loss of life.

The question for the forum was: how to encourage support for shared use of such sites, and to promote mutual understanding?

Dealing with fluctuating interest in religion

History shows that interest in religion ebbs and flows with time; how can we anticipate and deal with the consequences of such changes? In Eastern Europe, the Orthodox Church is reclaiming its traditional role in society, lost during the seventy years of Soviet dominion in the region. Many religious buildings

introduction 3