Chapter 3

.pdf

C H A P T E R

Intermediaries

Certain institutions facilitate the transfer of financial assets and obligations between various market partic-

ipants. These institutions intermediate between the suppliers of funds and the users of funds. Banks, for example, receive deposits from those with excess funds and lend to those with a shortage of funds. Inter-

mediaries have advantages in information gathering, transaction costs, economies of scale, and diversification of risk.

There are many financial intermediaries that facilitate the transfer of funds between savers and users of funds. One way to classify these institutions is by whether they accept deposits that customers can redeem on demand. Naturally, these types of institutions are called depository institutions. Nondepository institutions may accept investment funds but do not offer investors the ability to write checks or otherwise easily access their funds.

This chapter introduces these various institutions. An understanding of the role and purpose of the various intermediaries will help you deal with them more effectively throughout your business career.

DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS

Depository institutions accept deposits that customers can redeem on demand. They include commercial banks, savings and loans (S&Ls), mutual

52 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

savings associations, and credit unions. Although some brokerage houses now accept checkable deposits, they are not usually classified as depository institutions. Clearly the distinction between the different types of intermediaries is blurring as each institution attempts to capture business by expanding into new areas. This trend is likely to continue, and we will point out the major changes in this chapter.

Commercial Banks

We begin our study of institutions with commercial banks because of their pervasiveness in the economy. Individuals and businesses deal extensively with commercial banks on a regular basis. Additionally, banks are a major employer of finance graduates. We begin with a review of the history of banking in the United States because that is the only way to understand why we have our current and somewhat unusual banking system.

Brief History of Banking

In the 1600s the United States had a largely agricultural colonial economy unsuited to the rapid development of banking. Farmers purchased goods offered by local merchants on credit, and merchants in turn relied on credit offered by their British suppliers. This system worked well enough for limited agricultural development, but was unable to meet the needs of land-rich but cash-poor landowners who wanted to finance the development of their properties. To meet the needs of these landowners, land banks were established in some of the colonies. These land banks issued bank notes to make loans against property. Bank notes are promises to pay that are backed by the value of the property held by the land bank. Land banks tended to issue notes larger than the value of the land, and many failed.

During the Revolutionary War, British credit was eliminated. Several states chartered banks to help raise money to pay for the war effort. The first state-chartered bank was the Bank of North America, founded in Philadelphia in 1781. For the next 80 years, most growth in the banking industry occurred with state-chartered banks. These institutions accepted deposits and in turn issued bank notes that were payable on demand to the bearer. Bank notes became the money of early America. The problem with using bank notes as legal tender was that they were backed only by the assets of the issuing bank. If the bank ran into trouble, holders of bank notes stood to suffer losses. When these notes traveled outside the issuing bank's region, merchants were reluctant to accept them in payment for goods because they had no way of knowing whether the issuing bank was still in business.

Difficulties in financing the Civil War and the desire to provide a uniform currency prompted passage of the National Bank Acts of 1863 and 1864, which gave the federal government power to charter banks. Congress then gave nationally chartered banks the exclusive right to issue bank notes. The initial effect of the loss of the right to issue bank notes was a decline in state banking. Later, state banks began accepting deposits and offering checking accounts as their principal form of liability.

The role of private banks grew during the Industrial Revolution between 1890 and the 1920s. These private banks extended their business by acquiring commercial banks and merging underwriting activities (issuing stocks and bonds) with traditional com-

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

53 |

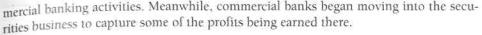

Glass-Steagall Act The Industrial Revolution came to an abrupt close with the Treat Depression in 1929. Only about 15,000 of the original 30,000 banks were still solvent by 1933. Responding to the failure of so many banks, Congress passed the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933 to prevent further losses to the public. The two most significant features of the Glass-Steagall Act were the introduction of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insurance and the separation of commercial banking from investment banking.

One of the principal causes of bank failures during the Depression was a series of bank runs. During a bank run, depositors withdraw their funds because they fear that they may lose their deposits if the bank fails. Bank customers often started runs on mere rumors of bank insolvency, which is the bank having more liabilities than assets. Banks became insolvent in the 1930s because the value of their assets (loans) became much lower. Consider the customer who hears that his bank may have taken a big loss from a real estate deal. The customer can carefully investigate the accuracy of the rumor, or just withdraw funds. The simplest and most expedient approach is to withdraw funds. As word circulates that a bank is losing deposits, other customers try to withdraw their funds while they still can. Banks cannot pay depositors all their money because most of it has been lent to borrowers. The result is that a rumor of a bank problem could actually cause the bank to collapse. This problem is unique to banks.

The Glass-Steagall Act introduced Federal Deposit Insurance. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures depositors against losses that may result from a bank's failure. After FDIC was in place, customers no longer felt the need to withdraw funds if a rumor suggested that a bank was in trouble, because they knew the government would make good on any losses they sustained up to the limit of FDIC coverage.

The FDIC is responsible for stopping bank runs in the 1930s and saving the industry from collapse.

Banks pay an insurance premium based on the risk of their investments, their equity, and their size. The FDIC uses these premiums to reimburse depositors when a bank fails. Currently the FDIC insures all accounts up to $100,000.

Figure 3.1 shows the number of banks in existence since 1920. In 1925 there were about 30,000 banks operating in the United States. This number dropped to under 15,000 by 1940. The number stayed fairly constant until 1985, when failures and consolidation led to a further decline. During the late 1990s, there were only one or two bank failures per year, yet the trend toward consolidation continues.

Investment banking is the sale of securities to the public. For example, if a firm wanted to sell stock to the public to raise funds for new projects, it could contact an investment banker. Investment banks buy securities issued by corporations for the very first time, called underwriting, and resell them to the public. Before the Glass-Steagall Act, commercial banks could engage in investment banking services. Many economists felt that some failures during the Depression were caused by banks investing in securities that failed to sell to the public. To preserve the safety of the banking industry, Congress mandated that commercial banks could not engage in investment banking. More

54 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

recently, economists have expressed doubts that investment banking caused many bank failures. Primarily small regional banks failed during the Depression, but most investment banking was done by the larger money center banks.

To limit excess competition among commercial banks, Regulation Q, a section of the Glass-Steagall Act, imposed limits on the amount of interest banks could pay on savings accounts and banned the payment of interest on checking accounts. These restrictions did not limit the growth of banking during the early part of the century, because interest rates were lower than the maximum limits imposed by Regulation Q and there were no other institutions offering checkable deposit accounts. The purpose of Regulation Q was to reduce the likelihood of a bank failing by limiting the cost of funds to banks. Because banks could not pay interest on checking accounts, these funds were essentially free.

Problems in the Industry Between 1940 and 1970, banks enjoyed an extended period of stability and profitability. Consider the advantages banks had during this period.

•The government granted charters only when applicants could show that their entry into the market would not harm existing banks. This restricted the competition for customers.

•Regulation Q guaranteed that banks would have a large source of low-cost funds (demand deposits) that banks could lend at market interest rates.

•Regulation Q required that banks pay a low rate of interest on savings accounts.

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

55 |

In effect, these regulations provided banks a protected customer base that gave them free money to invest. It took truly incompetent bank management to fail under these circumstances, which was exactly the intent of Congress.

This situation changed in the 1970s. Market interest rates rose well above the statutory limit and security firms began offering money market mutual funds that paid interest on checking accounts. The result of these changes was disintermediation: deposits flowing out of traditional intermediaries, such as banks and S&Ls, and into nontraditional intermediaries, such as brokerage firms.

Disintermediation caused serious problems for depository institutions. The loss of low-cost deposits meant that institutions had to replace the funds with higher-cost certificates of deposit (fixed-maturity securities that pay a much higher interest rate than regular deposits). The extra cost of these securities in turn led to losses and ultimately to the failure of many banks and thrifts. The term thrifts refers to S&Ls, mutual savings banks, and credit unions. Additionally, because the Federal Reserve did not control securities companies and these companies did not have to maintain reserves, a percentage of each deposit held at the Federal Reserve Bank to guard against liquidity concerns, the Fed was concerned about losing control of the money supply. (We will discuss the Fed's control over the money supply in Chapter 5.) This concern by the Fed led to new legislation.

Deregulation The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA) was the most significant banking legislation to be passed since the 1930s. A number of factors motivated Congress to pass the DIDMCA.

•Thrift institutions were experiencing devastating problems (we will discuss these problems later in this chapter).

•Limits on interest rates caused by Regulation Q were causing disintermediation (that is, the movement of funds out of banks).

•The Fed was losing membership because states tended to impose lower reserve requirements than the Fed imposed on nationally chartered banks. Because reserves do not earn interest income for the bank, large reserve requirements are costly.)

•Nondepository institutions were invading markets traditionally held by depository institutions and reducing bank profitability.

The combined effect of these problems was a seriously weakened financial system. The DIDMCA attempted to confront these issues with new legislation that provided what bankers called a level playing field on which to compete. The principal provisions of the DIDMCA include:

•Uniform reserve requirements for both state and nationally chartered banks. This effectively eliminated any advantage to being state chartered and stopped the switching of national charters to state charters.

•Regulation Q reform. The DIDMCA called for a gradual removal of interest rate ceilings. This transition was to take place over a 6-year period. Actually, virtually all limits were removed in less than 3 years.

56PART I Markets and Institutions

•Negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts were authorized. These accounts provided limited checking and permitted the payment of interest. They were designed to compete with the money market mutual funds offered by security houses. A NOW account is a cross between a savings account and a checking account because it pays interest and also permits a few checks to be written each month.

•S&Ls received broadened lending powers that included the authority to make consumer loans. This provision of the act was intended to shorten the average maturity of S&L portfolios. Prior to this, S&Ls were only allowed to make long-term mortgage loans.

The Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982 followed the DIDMCA 2 years later. This act effectively removed interest rate caps from banks and thrifts and allowed S&Ls to make all types of loans. Although these acts did slow the tide of disintermediation, they did not limit the increase in the cost of funds to banks and thrifts. Savings and loans, especially, continued to fail in the mid-1980s, although many of their problems ran deeper than an increase in the cost of funds. We discuss problems of the S&L industry later in this chapter.

Structure of Banking

To those outside the banking industry, the structure and ownership of banks may seem complex and inexplicable. Actually, it is the result of how the industry grew up and how bankers maneuvered around various regulations.

Dual Banking System The result of the various acts discussed so far is that all banks must operate with a charter. The United States is unique in that banks may obtain charters from either a state or the federal government. This is called a dual banking system. Nationally chartered banks must designate their affiliation by putting National or N.A. in their names. State banks cannot use these terms. In the past only national banks had access to Federal Reserve services. With the DIDMCA, Federal Reserve services became available to all banks, although they all now pay transaction fees. The principal remaining difference between state and national banks is who examines them.

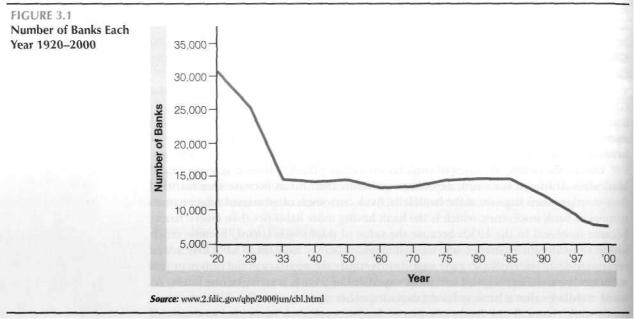

Figure 3.2 shows that despite the consolidation in the banking industry that has reduced the number of separate banks, the number of branches has actually increased. In the last 10 years, more than 10,000 new bank branches have been opened.

Bank Holding Companies Holding companies are shell companies that own other firms. Holding companies are popular in banking because they:

•Increase the flexibility of banks. For example, banks may sometimes use the holding company to circumvent interstate and intrastate bank branching restrictions.

•Increase access to capital.

•Reduce risk by allowing banks to diversify in ways that may not be possible otherwise.

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

57 |

Holding companies currently own over 70% of all banks, and over 90% of all deposits are in banks owned by holding companies.

The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 restricted bank holding companies that owned two or more banks from engaging in activities that were prohibited by the banks themselves. This regulation did not restrict the activities of one-bank holding companies.

One-bank holding companies (OBHC) grew rapidly during the 1960s. These firms operated businesses ranging from banking to agriculture and mining. In 1970 Congress amended the Bank Holding Company Act to include all holding companies. OBHCs had to divest themselves of any prohibited businesses. Today the holding company is still an important organizational form, particularly for expansion purposes.

Bank Branching Each state has the authority to restrict the number of branches banks can operate. By 1900 many states were very restrictive about branching. Their intent was to keep banks from becoming too large and powerful. They feared that large banks would take deposits out of some communities and not extend loans back. The most restrictive states were called unit states and they allowed only one full-service branch per bank. Others limited expansion to within one county or to some other geographic distance. Some states had no branching restrictions at all.

Most unit branching states were in the Midwest, whereas eastern states permitted limited branching and western states tended to permit statewide branching. In recent years most states have removed branching restrictions. The last unit bank state, Colorado, began permitting limited branching in 1991. One result of bank branching

58 PART I Markets and Institutions

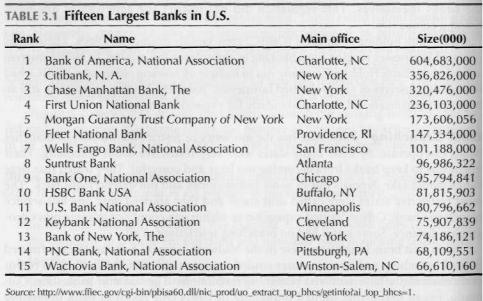

restrictions was that they kept banks from growing and capturing market share. For example, Table 3.1 lists the top 15 banks by size. Note that none of them are based in Texas—which had restrictive branching laws—despite its healthy economy and rapid growth. Three are based in North Carolina, which, despite not having as robust an economy as Texas, never restricted statewide branching. It is interesting to note that before consolidation in the banking industry there were many foreign banks that dwarfed the largest U.S. bank. For example, as recently as 1996 the Bank of Tokyo was over twice as large as the largest U.S. bank, Chase Manhattan. Now, the Bank of Tokyo is still the largest, but its lead has almost disappeared.

The McFadden and Douglas Amendment to the Bank Holding Co. Act effectively prohibited expansion across state lines (called interstate banking) except where expressly permitted by state law. These laws were in response to a fear by the American public of concentrating too much economic power in the hands of people not elected by the public. Congress assumed that if banks were restricted to a limited geographic area, this would in turn limit their size. The fact that the United States currently has about 8,400 banks, whereas most other industrialized nations have fewer than 300, attests to the accuracy of this assumption. In fact, Japan, England, and Canada each have fewer than 100 banks.

In 1975 Maine and New York became the first states to allow reciprocal interstate banking, meaning that banks from one state can branch into another if the second agrees to allow banks from the first to enter. In 1982 Alaska became the first state to allow free entry by any out-of-state bank as long as it was by acquiring an existing Alaskan bank. Currently, every state has some form of interstate banking regulation. Most require either reciprocal banking or entrance by acquisition.

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

59 |

The growth of interstate banking has resulted in extensive changes in the banking landscape. The number of banks chartered in the United States dropped from 14,870 in 1980 to about 8,400 today. This consolidation is expected to continue.

In September 1994 the U.S. Congress approved the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act, which allows banks to operate interstate branch networks. Beginning in 1997, the bill gave banks the ability to operate branches outside their home states, but only if the affected states allow it. Before passage of this bill, banks that wanted to extend services regionally or nationally had to incorporate separate banking subsidiaries. The bill permits bank holding companies to acquire banks outside their home states regardless of state laws. This bill is one reason we continue to see rapid consolidation within the banking industry.

Uses and Sources of Funds The assets of a bank are its cash balances, loans, investments, and deposits held at other banks and at the Federal Reserve. The liabilities of a bank are the deposits it accepts from customers, funds purchased (such as repurchase agreements or fed funds), and other borrowings. We often think of checking accounts as assets because we keep our transaction balances in them. But to a bank, your deposit is its liability because it owes the money to you.

Similarly, we think of loans as liabilities. Loans are the primary earning assets of a bank. It is correct to think of the lending function provided by commercial banks as their principal function. Over 65% of the average bank's assets are in its loan portfolio.

Changes in Bank Activities

The Federal Reserve Board regulates the activities of banks and bank holding companies. In 1933 the Glass-Steagall Act was passed to restrict banks from underwriting and selling corporate stocks and bonds. The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 said that the Federal Reserve Board is to limit bank holding companies to activities that are closely related to banking. Several factors motivated these early restrictions.

•Congress believed that certain commercial bank activities reinforced the stock market crash of 1929.

• The stock market crash led to the breakdown of the banking system.

•Transactions between commercial banks and their securities affiliates were believed to lead to abuses. For example, banks were lending money to customers for the purpose of purchasing securities that the banks had underwritten.

Table 3.2 lists some of the activities that the Federal Reserve board has approved and denied. Activities that the Federal Reserve board has approved generally include the usual banking services traditionally reserved for banks. Thus, loans and loan servicing, trust services, gold handling, and some investment advising are allowed. Also approved are some securities brokerage activities.

The Federal Reserve board denies banks the right to sell insurance; broker, own, or manage real estate investments; run armored car services or travel agencies; and underwrite most securities.

Study Tip

A/lake sure you understand the difference between brokers and underwriters. A broker facilitates the transfer of securities between the seller and the buyer, without taking ownership of the security, just as a real estate broker brings sellers and buyers together. Underwriting securities means that the underwriter takes ownership of the stock offering in order to transfer it to a buyer. Underwriting takes place when securities are first offered for sale. The underwriter prices the security, then markets it.

60 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Restrictions on Investment Banking Activities The Glass-Steagall Act bars commercial banks from certain investment banking activities. Banks can neither underwrite securities nor act as dealers in the secondary market for securities. There are two exceptions to these restrictions.

•Banks are permitted to underwrite and deal in U.S. government obligations.

•Banks are permitted to underwrite and deal in municipal general obligation bonds.

More recently developed securities, such as interest rate and currency swaps, are not specifically forbidden to commercial banks.

These restrictions have frustrated bankers' attempts to expand the scope of banking for many years. Commercial bankers complain that securities companies can offer traditional banking services while legislation restricts commercial banks from entering the securities business. The increased competition has lowered banks' profit margins.

Breaking Down Investment Banking Restrictions As the distinctions between the types of institutions and their products blurred, the financial services industry began pressing Congress to change Federal law. After years of debate and compromise, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was signed into law on November 12, 1999. This Act represents the most significant change in the U.S. financial services industry in 66 years. The Act permits banks, insurance companies, securities firms, and other financial institutions to affiliate under common ownership and offer their customers a complete range of financial services. Financial holding companies may now offer financial services previously outlawed. The events leading to this act are listed below.1

1933: Glass-Steagall Act separated commercial and investment banking.

1956: Bank Holding Company Act limited activities of companies with two or more bank subsidiaries to managing and controlling banks or activities closely related thereto.

1970s: Securities firms began offering deposit-like mutual fund accounts paying market interest rates with access to funds through drafts.