Chapter 3

.pdf

CHAPTER 3

1980: Monetary Control Act began the process of deregulating interest rates on deposit accounts, allowed NOW accounts, and expanded thrift powers.

1982: Garn-St. Germain Act authorized money market deposit accounts and prohibited bank holding companies from providing insurance activities, except in specifically enumerated instances.

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) approved formation of an operating subsidiary to engage in discount securities brokerage for the general public.

1983: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (hereafter simply "Board of Governors") approved a bank holding company's acquisition of a discount securities broker.

1987: Supreme Court approved OCC action allowing national banks to own discount brokerage subsidiaries.

Board of Governors approved bank holding company applications to underwrite and deal in certain ineligible securities at a 5-10% level.

1989: Board of Governors approved bank holding company applications to expand securities underwriting and dealing to all corporate debt and equity.

1990: Courts upheld OCC action allowing a national bank to form an operating subsidiary to sell insurance throughout the United States from a town with a population of 5,000 or less.

1995: Supreme Court decided national banks could sell annuities because they are investment products, not insurance.

1996: Board of Governors increased gross revenue limit on ineligible securities underwriting and dealing to 25% and eliminated cross-marketing restrictions.

Supreme Court ruled that state law could not significantly interfere with a national bank's exercise of its authority to sell insurance from a small town.

1998: Board of Governors approved Travelers' application to acquire Citicorp.

1999: President Clinton signed the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

As a result of these events, many banks have been aggressively expanding their brokerage service activities.

Self-Test Review Questions*

1.What is a unit banking state?

2.Why has the number of banks in the United States dropped in recent years?

3.What is a bank holding company?

4.What is a dual banking system?

Intermediaries 61

62 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Thrifts

In the last section we discussed commercial banks, which are the largest depository institutions. However, S&Ls, mutual savings, and credit unions—collectively called thrift institutions or thrifts—are important, though smaller, institutions. S&Ls were in the news in the early 1990s because of the huge losses occurring in the industry. This section investigates the causes of these losses.

Brief History

Mutual savings banks were the first thrifts in the country. The first one was chartered in 1816 in Boston. Mutual ownership means that there is no stock ownership. Technically, the depositors are the owners. There are currently about 500 mutual savings banks concentrated on the eastern seaboard. Most thrifts are state chartered because federal chartering of savings banks did not begin until 1978. Because they are state chartered, they are state regulated and state supervised as well.

Mutual savings banks and S&L associations are similar in many ways, but they do differ.

•Mutual savings banks are concentrated around the northeastern United States and S&Ls are spread throughout the country.

•Mutual savings banks may insure their deposits with the state or with the FDIC.

•Mutual savings banks are not as heavily concentrated in mortgages and have had more flexibility in their investing practices than S&Ls.

Because mutual savings banks and S&Ls are generally very similar and because few mutual savings banks remain, the balance of this section focuses on S&Ls.

Savings and Loan Associations The original mandate to the S&L industry was to provide funds for families wanting to buy a home. In the early part of the nineteenth century, commercial banks focused on short-term loans to businesses. Congress decided that part of the American dream was home ownership and to make this possible it passed regulations creating S&Ls and mutual savings institutions. These institutions were to aggregate depositors' funds and use the money to make long-term mortgage loans.

There were about 12,000 S&Ls in operation by the 1920s, but they were not an integrated industry. Each state regulated its own S&Ls and regulations differed substantially from state to state. Congress created the Federal Reserve System for commercial banks in 1913. No such system existed for S&Ls. Before any significant legislation could be passed, the Depression caused the failure of over 1,700 thrift institutions. In response to the problems facing the industry and to the loss of $200 million in savings, the Federal Home Loan Bank Act of 1932 was passed. This act created the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) and a network of regional home loan banks. The act gave thrifts the choice of being state or federally chartered.

In 1934 Congress established the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC, called Fizz-Lick by industry insiders) to insure deposits in much the same way as the FDIC. The institutions were not to take in checking accounts; instead, they

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

63 |

were authorized to offer savings accounts that paid slightly higher interest than was available from commercial banks.

S&Ls were successful low-risk businesses for many years. Their main source of funds was individual savings accounts that tended to be stable and inexpensive. Their primary assets were mortgage loans. Because real estate secured virtually all of these loans and its value increased steadily through the mid-1970s, loan losses were very small. Thrifts nrovided the fuel for the home building that for almost half a century was the centerpiece of America's domestic economy.

S&Ls in Trouble

Congress initially imposed a cap on the interest rate that S&Ls could pay on savings accounts. The theory was that if S&Ls obtained low-cost funds, they could make lowcost loans to home borrowers. The interest rate caps became a serious problem for S&Ls in the 1970s, when inflation rose. By 1979 inflation was 13.3%, which caused short-term interest rates to rise to over 15%, but S&Ls were restricted to paying a maximum of 5.5% on deposits.

At the same time, securities firms began offering a new product that circumvented interest rate caps. These new accounts were money market accounts that paid market rates on short-term funds. Though not insured, the bulk of the funds invested in money market funds were in turn invested in Treasury securities or commercial paper. Investors left the S&Ls for the high returns these accounts offered.

Most of the assets of S&Ls were long-term, fixed-rate mortgage loans. When the low-cost savings accounts fled, the S&L had to replace the funds with higher-cost CDs and borrowed money. This meant that the return on assets (loans) was fixed at low rates that could not be increased and the liabilities (savings accounts) were costly short-term securities.

S&L Crisis By the late 1970s most S&Ls were losing money rapidly. Many had no equity left. The problem this industry suffered is called the S&L crisis. Several factors contributed to the S&L crisis.

•The industry was essentially deregulated with the passage of the DIDMCA in 1980 and the Garn-St. Germain Act in 1982.

•The number of regulators was reduced as part of the Reagan administration's effort to make government less intrusive to businesses.

•Many states (especially California and Texas) reduced the criteria needed to own and manage an S&L.

•Fraud by S&L owners resulted in losses.

•Brokered deposits replaced small time deposits that left for the higher returns they received from money market mutual funds. This resulted in the rapid growth of many S&Ls.

•Deposits continued to be insured by the government, so depositors did not monitor the riskiness of S&L activities.

Study Tip

The S&L crisis refers to the problems the industry faced with rising interest rates, fixed-return loans, and mounting losses, which drove many S&Ls insolvent.

64 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Once Congress deregulated interest rates, S&Ls grew rapidly in the early 1980s because they could attract large sums of money by offering high interest rates. Deposit brokers searched the country each day for the S&Ls paying the highest rate and deposited funds in $ 100,000 blocks on behalf of their clients. By not depositing more than $ 100,000, the brokers made sure that the funds were covered by insurance. S&Ls were able to attract large amounts of money at low, risk-free interest rates because depositors knew that the deposits were guaranteed by the government. Depositors did not care what the S&L did with the funds, nor did they care about the risk taken by the S&L. Compare this situation to the market for corporate bonds. When a firm becomes more risky, investors demand a higher rate of return as compensation for that risk. With deposit insurance, the deposits were not risky, so depositors did not monitor the riskiness of the S&L. The government had too few regulators to adequately monitor the loans being made by S&Ls, so they were able to make high-risk loans unimpeded. Their motivation for making these high-risk loans was that they could charge customers higher interest rates and fees on higher-risk loans. Because many S&Ls had lost virtually all of their equity before being deregulated, they had little to lose if the loans did not pay. On the other hand, if the loans were repaid, there was the chance of returning the S&L to solvency. Unfortunately, the real estate market began weakening after 1985 and many of these loans defaulted.

The public became aware of the problems in the S&L industry in 1987 and 1988. To stop the losses, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) was passed in 1989. This act:

•Eliminated the FSLIC.

•Formed a new insurance agency called the Savings Association Insurance Fund (SAIF). The FDIC administers this new agency.

•Required S&Ls to have a 3% capital ratio by January 1995.

•Eliminated the Federal Home Loan Bank Board that had historically regulated S&Ls.

•Established the Resolution Trust Corporation to deal with insolvent S&Ls.

• Increased the penalties for officers of financial institutions convicted of fraud.

• Required that in the future S&Ls use 70% of their assets for housing loans.

• Banned S&Ls from some risky investments, such as junk bonds.

As a result of the failure of S&Ls and the FIRREA, the total assets of S&Ls have fallen since 1988.

Cost of the S&L Crisis The final cost of the S&L crisis has changed repeatedly over time. This is because many of the bad loans were secured by real estate that has changed in value over time. Additionally, regulators often are not aware of all of the bad loans and losses a given S&L will suffer until some time after the institution has been closed.

Initial estimates of the cost of the bailout were about $7 billion. In July 1988 the FHLBB increased its estimate to $15.2 billion. By October 1988 the estimate was up to $50 billion. Then, 3 months later, the estimate changed to nearly $100 billion. By August 1989, the General Accounting Office stated that the cost of the bailout was $166 billion.

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

65 |

In September 1994 the Resolution Trust Company estimated that the cost of the bailout was going to be around $112 billion. This reduction in the estimate was due to increased prices being paid for real estate acquired in the closing of defunct S&Ls and to falling interest rates that have increased the profitability of surviving S&Ls. The increased health of the surviving S&L industry is confirmed by the fact that only one S&L failed during the first 9 months of 1994. Final estimates put the cost at $145 billion. To put this loss into perspective, every person in the country will have to pay about $580 in additional taxes, not counting interest, just to pay for the losses the government suffered.

Since the S&L crisis in now well behind us, it may seem like an unnecessary review of ancient history to have discussed it in such detail. However, the lessons taught by this experience are far too important to forget. When the rules that govern the free market system are broken, in this case that higher returns should require greater risk, the system can fail. In retrospect, the collapse of the industry was very predictable as soon as legislation was passed that allowed an S&L to make high-risk loans with low-risk insured deposits. Because of FSLIC insurance, depositors did not restrict or monitor S&L risk taking, thus passing the responsibility on to the government, which would be held accountable for paying on losses. When the number of regulators was simultaneously reduced, disaster was guaranteed.

S&L Industry Today

The S&L industry has witnessed a substantial reduction in the number of institutions. Many have failed or been taken over by the Resolution Trust Corporation. Others merged with stronger institutions to avoid failure. The number of S&Ls declined about 54% between the end of 1987, when there were 3,600 S&Ls, and the end of 1999, when there were 1,640. Only one S&L failed during 1999. This suggests that both the industry and the economy are now stronger.2

One issue that has received considerable attention in recent years is whether the S&L industry is still needed. Observers who favor eliminating S&L charters altogether point out that there are now a large number of alternative mortgage loan outlets available for home buyers. A reasonable question to ask is whether there is a need for an industry dedicated exclusively to providing a service efficiently provided elsewhere in the financial system. Many S&Ls have been acquired by commercial banks. If this trend continues, the number of S&Ls is likely to fall even further.

Credit Unions

In this chapter, we have discussed mutual savings banks and savings and loans. A third type of thrift institution is the credit union, a financial institution that focuses on serving the banking and lending needs of its members. These institutions are also designed to serve the needs of consumers, not businesses, and are distinguished by their ownership structure and their common bond membership requirement. Most credit unions are small.

66 PART I Markets and Institutions

In the early 1900s commercial banks focused most of their attention on business borrowers. This left small consumers without a ready source of funds. Because Congress was concerned that commercial banks were not meeting the needs of consumers, it established S&L associations to help consumers obtain mortgage loans. In the early 1900s the credit union was established to help consumers with other types of loans. A secondary purpose was to provide a place for small investors to place their savings.

One reason for the growth of credit unions is the support they have received from employers. They realized that employee morale could be raised and time saved if banking facilities were readily available. In many cases, employers donate space on business property for the credit union to operate. The convenience of this institution soon attracted a large number of customers.

Credit unions are organized as mutuals; that is, they are owned by their depositors. A customer receives shares when a deposit is made. Rather than earning interest on deposited funds, the customer earns dividends. The amount of the dividend is not guaranteed, like the interest rate earned on accounts at banks. Instead, the amount of the dividend is estimated in advance and is paid if earnings make it possible.

The single most important feature of credit unions that distinguishes them from other depository institutions is the common bond member rule. The idea behind common bond membership is that only members of a particular association, occupation, or geographic region are permitted to join the credit union. A credit union's common bonds define its field of membership.

The most common type of common bond applies to employees of a single occupation or employer. For example, most state employees are eligible to join their state credit union. Similarly, the Navy Credit Union is open to all U.S. Navy personnel. Other credit unions accept members from the same religious or professional background.

Credit union membership has increased steadily from 1933 to the present. The steady increase is expected to continue because credit unions enjoy several advantages over other depository institutions. These advantages have contributed toward their growth and popularity.

•Employer support. As mentioned earlier, many employers recognize that it is in their best interests to help employees manage their funds. This motivates firms to support their credit unions.

•Tax advantages. Because credit unions are exempt from paying taxes by federal regulation, this savings can be passed on to the members in the form of higher dividends or lower service costs.

•Strong trade associations. Credit unions have formed many trade associations, which lower their costs and provide the means to offer services the institutions could not otherwise offer.

The main disadvantage of credit unions is that the common bond requirement keeps many of them very small. The cost disadvantage can prevent them from offering the range of services available from larger institutions. This disadvantage is not entirely equalized by the use of trade associations.

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

67 |

Self-Test Review Questions*

1What is a mutual association?

2What was the original intent of Congress in establishing S&L charters?

3Name one major factor that contributed to the thrift crisis.

4What is a common bond membership requirement?

NONDEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS

Nondepository institutions are intermediaries that accept funds for investment, but do not generally provide check-writing privileges. In recent years the distinction has blurred between nondepository and depository institutions because in some cases both offer nearly the same services. Still, this method of classifying the different types of institutions remains useful. In this section we discuss four types of nondepository institutions: insurance companies, brokerage firms, investment companies, and pension funds.

Insurance Companies

Types of Insurance

Insurance is classified by the type of undesirable event that is insured. The most common types of insurance are life insurance and property and casualty insurance. In its simplest form, life insurance provides cash to the heirs of the deceased. Many insurance companies offer policies that provide retirement benefits as well as life insurance. In this case the premium combines the costs of the life insurance with a savings program. The cost of life insurance depends on:

•The age of the insured

•Average life expectancies

•The health and lifestyle of the insured (e.g., whether the insured smokes)

•Operating costs of the insurance company

Life insurance policies tend to be long-term contracts.

Property and casualty insurance insures against losses due to accidents, fire, disasters, and other causes of loss of property. For example, marine insurance, which insures against the loss of boats and related goods, is the oldest form of insurance, predating even life insurance. Property and casualty policies tend to be short-term contracts subject to

68 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Commercial banks are in the business of providing banking services to individuals, small businesses, and large organizations. While the banking sector has been consolidating, it is

worth noting that far more people are employed in the commercial banking sector than in any other part of the financial services industry. Jobs in banking can be exciting and offer excellent opportunities to learn about business, interact with people, and build up a clientele.

Today's commercial banks are involved in more different types of business than ever before. You will find a tremendous range of opportunities in commercial banking. These range from branch-level services, where you might start out as a teller, to a wide variety of other services such

as leasing, credit card banking, international finance, and trade credit. Bank loan officers usually specialize in commercial, real estate, or consumer lending.

If you are well prepared and enthusiastic about entering the field, you are likely to find a wide variety of opportunities open to you. Trainee salaries in banking start around $27,000. A junior loan officer earns about $38,000 and a senior loan officer should earn $65,000 or more. Larger banks tend to offer higher salaries than banks with under $100 million in assets.

frequent renewal. Another significant distinction between life insurance policies and property and casualty policies is that the latter do not have a savings component. Property and casualty premiums are based on the probability of sustaining the loss.

Fundamentals of Insurance

All insurance is subject to a few basic principles:

•There must be a relationship between the insured and the beneficiary. Additionally, the beneficiary must be in a position to suffer potential loss.

•The insured must provide full and accurate information to the insurance company.

•The insured is not to profit as a result of insurance coverage. The goal of insurance is to make people whole again, not to provide them profits.

•If a third party compensates the insured for the loss, the insurance company's obligation is reduced by the amount of the compensation.

The purpose of these principles is to maintain the integrity of the insurance process. Without them, investors may be tempted to use insurance to gamble or speculate on future events. Taken to an extreme, this could undermine the ability of insurance companies to protect policyholders.

Why People Buy Insurance

The purpose of insurance is for individuals and businesses to transfer risk to others. Individuals and businesses have the option of self-insuring. When self-insured, any unex-

CHAPTER 3 Intermediaries |

69 |

pected losses must be paid for without outside help. The alternative is to pay an outsider to share in the risk. The outsider is in the business of evaluating risk and predicting the l'kelihood of incurring a loss. This lets the outsider properly price the risk it is agreeing

to incur.

The price the insurer must charge is equal to the expected value of the loss plus a

profit margin. The expected value of the loss is equal to the probability of a loss multiplied by the expected size of the loss. For example, if there is one chance in 1,000 that a house will burn down during a given year, and the house is valued at $100,000, then the insurance premium should be $100 per year (0.001 x $100,000) plus profit. Because insurance will cost more than the expected value of the loss by the amount of profit the insurance company charges, why are people so willing to pay an outsider to share in the risk? It is because most people are risk averse. This means that people prefer to pay a certainty equivalent (the insurance premium) than to accept the gamble. In other words, because people are risk averse, they prefer to buy insurance and know what their wealth will be with certainty than run the risk that their wealth may fall substantially.

Growth and Organization of Insurance Companies

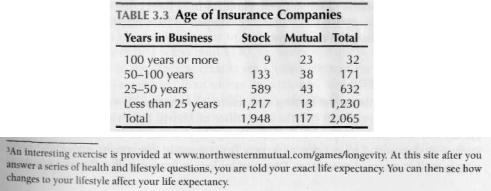

Table 3.3 shows that insurance companies can be organized as either stock or mutual firms. A stock company is owned by stockholders and has the objective of making a profit. Most new insurance companies organize as stock corporations. As Table 3.3 shows, only 117 of 2,065 insurance companies are organized as mutuals.

Assets and Liabilities of Life Insurance Companies

Life insurance companies derive funds from two sources. First, they receive premiums that result in future obligations that must be met when the insured dies. Second, they receive premiums paid into pension funds managed by the life insurance company. These funds are long term in nature.

A life insurance company can predict with a high degree of accuracy when death benefits must be paid by using actuarial tables that predict life expectancies. For example, Table 3.4 lists the expected life of people at various ages. A 25-year-old woman can expect to live another 55.2 years. Because insurance companies have many beneficiaries, the law of averages tends to make their predictions quite accurate.3

70 |

PART I Markets and Institutions |

Insurance companies also have invested heavily in mortgages and real estate over the years. In 1992, about 17.9% of life insurance assets were invested in either mortgage loans or directly in real estate. This percentage is down substantially from historic levels. The decline in mortgage investment has been offset by increased investment in corporate bonds and government securities.

The shift to stocks and bonds may be the result of losses suffered by some insurance companies in the late 1980s. As insurance companies competed against mutual funds and money market funds for retirement dollars, they found that they needed higherreturn investments. This led some insurance companies to invest in real estate and junk bonds. Deteriorating real estate values brought on by overbuilding during the 1980s caused some firms to suffer large losses. The combination of large real estate losses and junk bond investment contributed to the failure of several large firms in 1991. The best known examples were the failures of Executive Life and Mutual Benefit Life, with assets of $15 billion and $14 billion, respectively.

Insurance Regulation

Insurance companies are subject to less federal regulation than many other financial institutions. The primary federal regulator is the Internal Revenue Service, which administers special taxation rules. Most insurance regulation occurs at the state level. The purpose of this regulation is to protect policyholders from losses due to the insolvency of the company. To accomplish this, insurance companies have restrictions on their asset composition and minimum capital ratio.

Brokerage Firms

Brokerage firms facilitate the buying and selling of securities. If you want to buy 100 shares of Microsoft, you can call the local office of Merrill Lynch and request that the broker buy the shares on your behalf. Brokerage houses can be classified as either full service or discount. Full-service brokerage firms provide investment advice and planning as well as transaction services. Discount brokerage firms usually offer limited advice