прагматика и медиа дискурс / Teun A van Dijk - News Analysis

.pdf

290 |

CONCLUSIONS |

demic career, these insights may have played a muted role in the background but only recently emerged as a more explicit program. To be sure, as for most of us, excuses are easy. When engaged as 1 was in the development of linguistic poetics, text grammar, discourse pragmatics, or the psychology of text processing, there seemed to be few obvious ways to realize such a program. The same may be true for most individuals working on similarly technical topics in other disciplines of the humanities, as well as in mathematics, medicine, or the natural sciences. After all , a job must be done for which we are hired: develop new theories, describe old and new phenomena, and educate students. Until we realize that such discourses are also culturally, socially and politically situated. The dominante, choice or priorities of paradigms, theories, topics, terms, and technology are seldom, if ever, innocent. This becomes apparent as soon as we unravel and provide answers to persistent questions such as whose language, whose literature, whose arts, whose history, whose bodies, whose minds, or whose technology have we usually been studving, and especiallv: in whose interests.

These well-lmown, but consistently ignored, implications of a few decades of marginalized critical scholarship are even more relevant in the social sciences. They hardly need to be spelled out again. Nor should be repeated the undoubtedly naive, facile, and somewhat outdated slogans that demand science about people to be science for the people. The real problem lies in the translation of our compliance with such demands for true academic democracy into serious, that is, effective research programs. It is easy to call for social relevance of our work, but when do its results go beyond the statement of a social problem or beyond the recommendation of a social policy which will benefit most who need it less? In other words, when do our analyses actually contribute, maybe even indirectly, to the solution of the no-less trivial sounding list of real issues, such as severe or subtle inequality, poverty, or oppression?

In the margin of dominant scholarship of the past two decades, serious attempts have been made to answer at least fragments of these awkward questions. Feminist research has shown, among other things, that questions about whose language, literature, history, body, mind, work, or social role were traditionally answered within a dominant context of male practices, from which women were banned. The same is true for the ethnic studies that emerged from centuries of Black resistance and decades of focused Black scholarship directed against slavery, Reconstruction, apartheid, segregation, and the more subtle forms of discrimination and racism of today in white academic research. Such endeavors in the realms of gender and race continue and further enrich what Marxistor socialist-inspired research has long stated for the realm of class; and, they run parallel with similar political and academic fights by Third World peoples against old or new colonialisms and exploitation. In other words, many of those who were at first invisible or

6. CONCLUSIONS |

291 |

at best treated as problems in academic theories, textbooks, classrooms, the mass media, and other forms of dominant discourses have now made themselves visible and heard, while at the same time reversing their earlier treatment by relocating the problem to the dominant (Northwestern, middle class, male, white) cultures.

Manv of these developments defy traditional political divisions such as those between left and right, liberal and conservative, East and West. Women know that in many respects sexism is classless; and academic women know that they may expect more serious, while more consequential, chauvinism from some of their male colleagues, than from the blue color worker. People of color or other immigrants in our societies know that, although in different guises, racism comes from the rich and the poor, from men and women, from the educated or the ill-educated, and from left and rightthat is from all those who have power because they are members of the white dominant group. The peoples of the Third World have demonstrated that their problems and interests do not follow primarily the East-West, but rather the North-South boundarv.

The students who in the fall of 1986 demonstrated in Paris and elsewhere did more than recall the cry for academic and social democracy that our generation made in 1968. Generally thought to be apolitical, they protested against racism against their Black and other immigrant against growing competition in education, against the increasing power of technology, and against the pervasive lack of opportunities in a society that seemed to have resigned in accepting unemployment as a natural condition of life. Similarlv, the ecological and antinuclear movements also appear to make demands for an environment and a world free of pollution and genocidal weaponry that cannot simply be explained in terms of left or right. True, the social and political left may have more experience and more theory that might make it more sensitive to all these developments, but it also showed that across different social realms this is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition.

It is within these intimately connected fields of society, polity, and academy from which the studies in this book, as well as much of my other later work, draws part of their inspiration, motivation, and goals. This does not mean that as a western, white, middle-class, male professor (in any order of these categories) I can speakfor Third World, Black, or immigrant peoples, nor for squatters or others in our society who are powerless despite their resistance. By position and competence I feel only entitled to show solidarity by critically analyzing the social discourse of those who are in control, and whom I know so well because they happen to belong to the same

categories that I do.

My contribution to such an understanding of some of the central, while ideological, processes of hegemony is further limited by the constraints of

292 |

CONCLUSIONS |

academic discourse previously mentioned. We cannot fight social change in immediate practices unlike the pressure group or social movement such as the squatters who occupy the houses that are left empty by real estate speculators, Greenpeace activists who block dumping of nuclear or industrial waste into our rivers or oceans, or the women in Greenham Common who for years beleaguer a nuclear airforce base. Nor do we have the potential power of the journalist whose daily discourse about immediate political and social events reaches thousands if not millions. If any, our influence is indirect and distant, e.g., through publication of critical work and by educating tomorrow's elite.

This contribution to the construction of a counterideology, however, can be effective only through the persuasíve means of scholarly discourse, i.e., by the power of theoretical, analytical, or methodological argument. Topic choice is free and easy enough. Analyzing the representation of the powerless in the mass-mediated reproduction of the ideology that underlies and legitimates their subjugation is hardly more than one choice among many others. We have to learn to ask the right questions, forge new terminologies, or rebuild dominant theories. We may have to leave the familiar field of our own discipline, simply because the problems under study are too complex to be framed in, and reduced to, simply, monodisciplinary analysis and understanding.

This, then, has been the formidable task of this and a few of my other recent books on the news media and on the reproduction of racism. I am afraid that as yet only little progress has been made. To study the ideological role of the media, we need to know about the details of its discursive practices. Formed in a tradition of abstract, structuralist, theory formation in linguistics and discourse analysis, I may at most dispose of a few tools for systematic analysis of these practices. Despite their sometimes apparent sophistication, however, these instruments often appear to be too blunt to unravel the subtleties of social discourse. The same is true for the undoubtedly necessary cognitive machinery we now have at our disposal to analyze the mental dimensions of discourse—and hence news—production and understanding that are central in the ideological process. But again, even when we have urged, with others, to focus on social cognition, our actual theoretical insights hardly allow for a detailed explanation of these cognitive foundations of discourse, interaction, and ideology. Finally, at the more global level of societal structures, the social sciences may have taught us about some of the abstract mechanisms of power, dominance, and institutions but as yet fail to show the precise workings at the microlevel of text, talk, and everyday interaction also in the field of mass communication. In other words, several disciplines are involved, and none of them has been able to bridge the theoretical gaps or to deliver the analytical instruments that allow us to study the full complexity of the structures and functions of

6. CONCLUSIONS |

293 |

the media. Maybe we at least know the right questions, if not their answers. Maybe even our questions are misguided.

Obviously, the more critical questions should not be expected to come from the dominant scholarly paradigma themselves. These have consistently shown to prefer fashionable hobbyhorses over more substantial, let alone socially relevant, problem formulations, if they were theoretically or empirically adequate at all. Anyone can provide detailed examples from his or her own discipline. We remember the fate of decades of behaviorism, of simplistic learning or effect theories, of cybernetics and information theory, of scores of persuasion theories, maybe soon joined by much of semiotics or schema theories. Surely much of our scientific progress is only illusory , trial and error, and often our academie playground is only filled with the beautiful theoretical self-made toys that fascinate so many of us.

These observations suggest (and persuaded me) that we might as well have the problems formulated by those in the real world who have no access to the power or the resources for their analysis and solution. I trust that in most disciplines (at least in those I know) this will engender vast amounts of relevant topics to keep us busy for a long time. Although these problems are often rooted in the objective, material, socioeconomic conditions of class, race, gender or region dominance, they have their autonomous ramifications anywhere in the areas the humanities and social sciences are bcund to study: history, the arts, literature, discourse, communication, the media, education, as well as other societal and political structures and institutions.

Theories developed in this perspective must, by necessity, be grounded in an empirical foundation. They must be systematic and precise because otherwise they simply won't work. They are no longer limited to one discipline because the problems involved are always multidisciplinary. Research projects become functional elements in larger and more enduring research programs, which are no longer simply stopped when the fashionable theory has been abolished. Application is no longer the task of our second-rated colleagues but the fmal goal of the theorist of any academic work. The complexity of the problems will stimulate creativity and collaboration and prevent us from resigning in paradigrnatic routine research. Teaching will train students less in memorizing theories, doing analyses, or running experiments, which a decade later appear outdated if not irrelevant and uninteresting. Finally, we may no longer appear to be helpless academics who will at best contribute to the cultural favade of those in power or who at worst sustain that power by our scientifically-based policy recommendations or legitimation. Rather, we may develop some counterpower by being able to provide our share of alternative ideologies, policies, and practices.

This means that we must redefine the goals and issues of our work in language, discourse, communication, cognition, and interaction. These and other closely related areas, all dealing with symbolic practices, provide an

294 |

CONCLUSIONS |

ideal domain of purposeful exploration and experimentation. The media and education are only two of the large target areas for such work. This book and my other recent work refers to many critical studies by scholars from many countries who are tiying to show how. We have already mentioned social and academic developments that also suggest why. Again, this is only a beginning. Before the turn of the century and the millennium, this should lead not simply to a new paradigm among many others but to a completely different way of doing academic work. Similarly, in the study of communication, we do not simply want a linguistic, discourse or cognitive tum but an overall critical turn.

When the fine Brazilian song writer and singer Chico Buarque rightly observes that people's pain doesn't appear in the paper, we may paraphrase him by saying that the same is true for most of our academic discourse. The time has come for change.

APPENDIX

List of regions, countries and newspapers and the frequencies and languages of anides scored about the events in Lebanon

(Compiled by Piet de Geus)

N of artides scored

15 16 17 Tot. Language

A.NORTH AMERICA

1.Canada

102 |

Ottowa Citizen |

2 |

2 |

2 |

6 |

English |

2. U.S.A. |

|

3 |

4 |

5 |

12 |

English |

202 |

Los Angeles Times |

|||||

203 St. Louis Post-Dispatch |

3 |

4 |

0 |

7 |

English |

|

205 |

The New York Times |

5 |

8 |

5 |

18 |

English |

206 The Wall Street Journal |

1 |

3 |

O |

4 |

English |

|

|

TOTAL REGION |

14 |

21 |

12 |

47 |

|

|

|

|

|

— |

|

|

B.CENTRAL AMERICA

9.Cuba

901 Granma |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 Spanish |

(continued)

295

296 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

APPENDIX |

|

|

APPENDIX |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

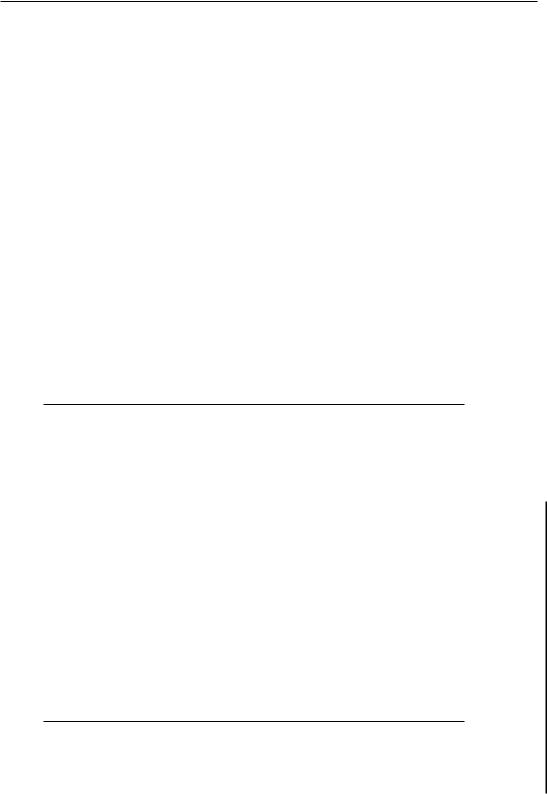

(Continued) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

N of articles scored |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15 |

16 |

17 |

Tot. |

Language |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

11. |

El Salvador |

|

|

|

1 |

3 |

Spanish |

|

1101 El Diario de Hoy |

1 |

1 |

||||

14. |

Guatemala |

3 |

4 |

5 |

12 |

Spanish |

|

|

1401 Diario el Gráfico |

||||||

|

1402 El Imperial |

|

O |

2 |

5 |

7 |

Spanish |

17. |

Jamaica |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1701 Daily Gleaner |

1 |

2 |

0 |

3 |

English |

|

19.Mexico

|

1901 Excelsior |

2 |

0 |

4 |

6 |

Spanish |

|

1902 Uno Más Uno |

1 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

Spanish |

21. |

Nigaragua |

|

|

|

7 |

Spanish |

|

2101 Barricada |

2 |

3 |

2 |

||

|

2102 El Nuevo Diario |

3 |

0 |

2 |

5 |

Spanish |

|

2103 La Prensa |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

Spanish |

23. |

Puerto Rico |

|

2 |

1 |

4 |

Spanish |

|

2301 El Mundo |

1 |

||||

|

TOTAL REGION |

15 |

17 |

25 |

57 |

|

C. SOUTH AMERICA

30. |

Argentina |

|

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Spanish |

|

3002 La Prensa |

|

|||||

|

3003 La Razón |

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Spanish |

32. |

Brazil |

|

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Portugese |

|

3201 Jornal do Brasil |

||||||

|

3202 0 Estado de Sáo Paulo |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

Portugese |

|

|

3203 O Globo |

IN |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Portugese |

33. |

Chile |

|

|

|

1 |

6 |

Spanish |

|

3301 El Mercurio |

|

2 |

3 |

|||

34. |

Colombia |

|

|

3 |

1 |

6 |

Spanish |

|

3401 El Tiempo |

|

2 |

||||

35. |

Ecuador |

|

|

7 |

4 |

12 |

Spanish |

|

3501 El Comercio |

|

1 |

||||

38.Paraguay

|

3801 ABC Color |

3 |

2 |

7 |

12 |

Spanish |

41. |

Uruguay |

|

|

|

|

Spanish |

|

4101 El Día |

5 |

4 |

7 |

16 |

|

42. |

Venezuela |

|

|

4 |

8 |

English |

|

4201 The Daily Joumal |

1 |

3 |

|||

|

4203 El Nacional |

1 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

Spanish |

|

4204 El Universal |

1 |

10 |

0 |

11 |

Spanish |

|

TOTAL REGION |

21 |

37 |

27 |

85 |

|

(continuad)

297

APPENDIX

(Continued)

N of articles scored

15 16 17 Tot. Language

D.WESTERN EUROPE

43. |

Austria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4302 Die Presse |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

German |

|

44. |

4303 |

Salzburger Nachrichten |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

German |

Belgium |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4401 Het Laatste Nieuws |

1 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

Dutch |

|

|

4403 Le Soir |

2 |

8 |

3 |

13 |

French |

|

45. |

Denmark |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4501 Berlingske Tidende |

0 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

Danish |

|

|

4502 |

Information |

1 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

Danish |

|

5403 |

Politiken |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

Danish |

46.England

4601 Daily Express |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

English |

|

4602 |

Daily Mail |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

English |

4603 |

Daily Mirror |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

English |

4605 |

The Daily Telegraph |

1 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

English |

4606 The Guardian |

1 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

English |

|

4607 Morning Star |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

English |

|

4609 Sing Tao |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

English |

|

4611 |

The Times |

1 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

English |

48.France

4801 Le Figaro |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

French |

|

4802 |

France-Soir |

1 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

French |

4804 |

International Herald Tribune |

2 |

5 |

1 |

8 |

French |

4805 |

Libération |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

French |

4807 Le Monde |

0 |

10 |

5 |

15 |

French |

|

49.Greece

4901 |

Akropolis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Greek |

4903 |

Kathimerini |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Greek |

50.Iceland

|

5001 Morgunbladid |

1 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

Icelandic |

|

51. |

Ireland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5101 |

The Irish Times |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

English |

52. |

Italy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5201 Corriere della Sera |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

|

5204 |

La Repubblica |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

5205 La Stampa |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

|

5206 |

L'Unitá |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

54.The Netherlands

5401 |

Algemeen Dagblad |

1 |

7 |

2 |

10 |

Dutch |

5402 |

NRC Handelsblad |

4 |

3 |

4 |

11 |

Dutch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(continued)

D. WESTERN EUROPE

43. |

Austria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4302 Die Presse |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

German |

|

44. |

4303 |

Salzburger Nachrichten |

1 |

3 |

O |

4 |

German |

Belgium |

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

4401 Het Laatste Nieuws |

1 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

Dutch |

|

|

4403 Le Soir |

2 |

8 |

3 |

13 |

French |

|

45. |

Denmark |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4501 |

Berlingske Tidende |

0 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

Danish |

|

4502 Information |

1 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

Danish |

|

|

5403 Politiken |

1 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

Danish |

|

46. |

England |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4601 Daily Express |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

English |

|

|

4602 |

Daily Mail |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

English |

|

4603 |

Daily Mirror |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

English |

|

4605 |

The Daily Telegraph |

1 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

English |

|

4606 The Guardian |

1 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

English |

|

|

4607 Morning Star |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

English |

|

|

4609 Sing Tao |

0 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

English |

|

|

4611 |

The Times |

1 |

7 |

0 |

8 |

English |

48.France

4801 Le Figaro |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

French |

|

4802 |

France-Soir |

1 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

French |

4804 |

International Herald Tribune |

2 |

5 |

1 |

8 |

French |

4805 Libération |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

French |

|

4807 Le Monde |

0 |

10 |

5 |

15 |

French |

|

49.Greece

|

4901 Alarpolis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Greek |

|

4903 Kathimerini |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

Greek |

50. |

Iceland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5001 Morgunbladid |

1 |

4 |

3 |

8 |

Icelandic |

51. |

Ireland |

|

|

|

|

|

|

5101 The Irish Times |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

English |

52. |

Italy |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

5201 Corriere della Sera |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

|

5204 La Repubblica |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

5205 La Stampa |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

|

5206 L'Unitá |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

Italian |

54.The Netherlands

5401 |

Algemeen Dagblad |

1 |

7 |

2 |

10 |

Dutch |

5402 |

NRC Handelsblad |

4 |

3 |

4 |

11 |

Dutch |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(continued)

APPENDIX |

299 |

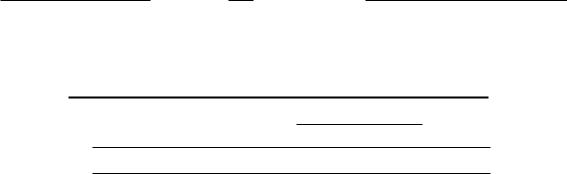

APPENDIX

(Continued)

N of articles scored

15 16 17 Tot. Language

67.Poland

68. |

6701 |

Tiybuna Ludu |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

Polish |

Romania |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

German |

||

|

6801 Neuer Weg |

||||||

69. |

U. S. S. |

|

O |

0 |

1 |

1 |

Russian |

|

6901 |

Izvestia |

|||||

70. |

6902 |

Pravda |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Russian |

Yugoslavia |

O |

O |

1 |

1 |

Serbo-Croat |

||

|

7001 Borba |

||||||

|

7004 |

Politika |

O |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Serbo-Croat |

|

|

|

1 |

14 |

13 |

|

|

F.MIDDLE EAST/NORTH AFRICA

71.Algeria

75. |

7101 El Moudjahid |

1 |

3 |

9 |

13 |

French |

Iran |

1 |

6 |

0 |

7 |

English |

|

|

7501 Kayhan International |

|||||

77. |

7504 Teheran Times |

1 |

1 |

0 |

2 |

English |

Israel |

1 |

10 |

0 |

11 |

Hebrew |

|

|

7701 Ha'aretz |

|||||

80. |

7703 Ma'ariv |

3 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

Hebrew |

Lebanon |

10 |

19 |

25 |

54 |

French |

|

|

8004 Le Réveil |

82.Morocco

8201 |

Al Alam |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

French |

8203 |

L'Opinion |

0 |

6 |

5 |

11 |

French |

83. Qatar |

|

2 |

3 |

O |

5 |

English |

8301 |

Daily Gulf Times |

|||||

|

TOTAL REGION |

19 |

51 |

39 |

109 |

|

G. AFRICA

90. Angola |

O |

1 |

0 |

1 |

Portugese |

9001 Jornal de Angola |

97.Congo (People's Republic of the)

106. |

9701 Mweti |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

French |

Ivory Coast |

1 |

7 |

4 |

12 |

French |

|

107. |

10601 Fraternité Matin |

|||||

Kenya |

1 |

4 |

1 |

6 |

English |

|

110. |

10701 Daily Nation |

|||||

Madagascar |

0 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

French |

|

|

11003 Matin |

(continued)