- •Contents

- •Symbols and Abbreviations

- •Symbols

- •Greek Symbols

- •Subscripts

- •Abbreviations

- •Preface

- •Road Map of the Book

- •The Arrangement

- •Suggested Route for the Coursework

- •First Semester

- •Second Semester

- •Suggestions for the Class

- •Use of Semi-empirical Relations

- •1 Introduction

- •1.1 Overview

- •1.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •1.1.2 Coursework Content

- •1.2 Brief Historical Background

- •1.3 Current Aircraft Design Status

- •1.3.1 Forces and Drivers

- •1.3.2 Current Civil Aircraft Design Trends

- •1.3.3 Current Military Aircraft Design Trends

- •1.4 Future Trends

- •1.4.1 Civil Aircraft Design: Future Trends

- •1.4.2 Military Aircraft Design: Future Trends

- •1.5 Learning Process

- •1.6 Units and Dimensions

- •1.7 Cost Implications

- •2 Methodology to Aircraft Design, Market Survey, and Airworthiness

- •2.1 Overview

- •2.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •2.1.2 Coursework Content

- •2.2 Introduction

- •2.3 Typical Design Process

- •2.3.1 Four Phases of Aircraft Design

- •2.3.2 Typical Resources Deployment

- •2.3.3 Typical Cost Frame

- •2.3.4 Typical Time Frame

- •2.4 Typical Task Breakdown in Each Phase

- •Phase 1: Conceptual Study Phase (Feasibility Study)

- •Phase 3: Detailed Design Phase (Full-Scale Product Development)

- •2.4.1 Functional Tasks during the Conceptual Study (Phase 1: Civil Aircraft)

- •2.4.2 Project Activities for Small Aircraft Design

- •Phase 1: Conceptual Design (6 Months)

- •Phase 3: Detailed Design (Product Development) (12 Months)

- •2.5 Aircraft Familiarization

- •Fuselage Group

- •Wing Group

- •Empennage Group

- •Nacelle Group

- •Undercarriage Group

- •2.6 Market Survey

- •2.7 Civil Aircraft Market

- •2.8 Military Market

- •2.9 Comparison between Civil and Military Aircraft Design Requirements

- •2.10 Airworthiness Requirements

- •2.11 Coursework Procedures

- •3 Aerodynamic Considerations

- •3.1 Overview

- •3.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •3.1.2 Coursework Content

- •3.2 Introduction

- •3.3 Atmosphere

- •3.4 Fundamental Equations

- •3.5.1 Flow Past Aerofoil

- •3.6 Aircraft Motion and Forces

- •3.6.1 Motion

- •3.6.2 Forces

- •3.7 Aerofoil

- •3.7.1 Groupings of Aerofoils and Their Properties

- •NACA Four-Digit Aerofoil

- •NACA Five-Digit Aerofoil

- •NACA Six-Digit Aerofoil

- •Other Types of Aerofoils

- •3.9 Generation of Lift

- •3.10 Types of Stall

- •3.10.1 Gradual Stall

- •3.10.2 Abrupt Stall

- •3.11 Comparison of Three NACA Aerofoils

- •3.12 High-Lift Devices

- •3.13 Transonic Effects – Area Rule

- •3.14 Wing Aerodynamics

- •3.14.1 Induced Drag and Total Aircraft Drag

- •3.15 Aspect Ratio Correction of 2D Aerofoil Characteristics for 3D Finite Wing

- •3.16.1 Planform Area, SW

- •3.16.2 Wing Aspect Ratio

- •3.16.4 Wing Root (Croot) and Tip (Ctip) Chord

- •3.16.6 Wing Twist

- •3.17 Mean Aerodynamic Chord

- •3.18 Compressibility Effect: Wing Sweep

- •3.19 Wing Stall Pattern and Wing Twist

- •3.20.1 The Square-Cube Law

- •3.20.2 Aircraft Wetted Area (AW) versus Wing Planform Area (Sw)

- •3.20.3 Additional Vortex Lift

- •3.20.4 Additional Surfaces on Wing

- •3.21 Finalizing Wing Design Parameters

- •3.22 Empennage

- •3.22.1 H-Tail

- •3.22.2 V-Tail

- •3.23 Fuselage

- •3.23.2 Fuselage Length, Lfus

- •3.23.3 Fineness Ratio, FR

- •3.23.4 Fuselage Upsweep Angle

- •3.23.5 Fuselage Closure Angle

- •3.23.6 Front Fuselage Closure Length, Lf

- •3.23.7 Aft Fuselage Closure Length, La

- •3.23.8 Midfuselage Constant Cross-Section Length, Lm

- •3.23.9 Fuselage Height, H

- •3.23.10 Fuselage Width, W

- •3.23.11 Average Diameter, Dave

- •3.23.12 Cabin Height, Hcab

- •3.23.13 Cabin Width, Wcab

- •3.24 Undercarriage

- •3.25 Nacelle and Intake

- •3.26 Speed Brakes and Dive Brakes

- •4.1 Overview

- •4.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •4.1.2 Coursework Content

- •4.2 Introduction

- •4.3 Aircraft Evolution

- •4.4 Civil Aircraft Mission (Payload-Range)

- •4.5 Civil Subsonic Jet Aircraft Statistics (Sizing Parameters and Regression Analysis)

- •4.5.1 Maximum Takeoff Mass versus Number of Passengers

- •4.5.2 Maximum Takeoff Mass versus Operational Empty Mass

- •4.5.3 Maximum Takeoff Mass versus Fuel Load

- •4.5.4 Maximum Takeoff Mass versus Wing Area

- •4.5.5 Maximum Takeoff Mass versus Engine Power

- •4.5.6 Empennage Area versus Wing Area

- •4.5.7 Wing Loading versus Aircraft Span

- •4.6 Civil Aircraft Component Geometries

- •4.7 Fuselage Group

- •4.7.1 Fuselage Width

- •4.7.2 Fuselage Length

- •4.7.3 Front (Nose Cone) and Aft-End Closure

- •4.7.4 Flight Crew (Flight Deck) Compartment Layout

- •4.7.5 Cabin Crew and Passenger Facilities

- •4.7.6 Seat Arrangement, Pitch, and Posture (95th Percentile) Facilities

- •4.7.7 Passenger Facilities

- •4.7.8 Cargo Container Sizes

- •4.7.9 Doors – Emergency Exits

- •4.8 Wing Group

- •4.9 Empennage Group (Civil Aircraft)

- •4.10 Nacelle Group

- •4.11 Summary of Civil Aircraft Design Choices

- •4.13 Military Aircraft Mission

- •4.14.1 Military Aircraft Maximum Take-off Mass (MTOM) versus Payload

- •4.14.2 Military MTOM versus OEM

- •4.14.3 Military MTOM versus Fuel Load Mf

- •4.14.4 MTOM versus Wing Area (Military)

- •4.14.5 MTOM versus Engine Thrust (Military)

- •4.14.6 Empennage Area versus Wing Area (Military)

- •4.14.7 Aircraft Wetted Area versus Wing Area (Military)

- •4.15 Military Aircraft Component Geometries

- •4.16 Fuselage Group (Military)

- •4.17 Wing Group (Military)

- •4.17.1 Generic Wing Planform Shapes

- •4.18 Empennage Group (Military)

- •4.19 Intake/Nacelle Group (Military)

- •4.20 Undercarriage Group

- •4.21 Miscellaneous Comments

- •4.22 Summary of Military Aircraft Design Choices

- •5 Aircraft Load

- •5.1 Overview

- •5.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •5.1.2 Coursework Content

- •5.2 Introduction

- •5.2.1 Buffet

- •5.2.2 Flutter

- •5.3 Flight Maneuvers

- •5.3.1 Pitch Plane (X-Z) Maneuver (Elevator/Canard-Induced)

- •5.3.2 Roll Plane (Y-Z) Maneuver (Aileron-Induced)

- •5.3.3 Yaw Plane (Z-X) Maneuver (Rudder-Induced)

- •5.4 Aircraft Loads

- •5.4.1 On the Ground

- •5.4.2 In Flight

- •5.5.1 Load Factor, n

- •5.6 Limits – Load and Speeds

- •5.6.1 Maximum Limit of Load Factor

- •5.6.2 Speed Limits

- •5.7 V-n Diagram

- •5.7.1 Low-Speed Limit

- •5.7.2 High-Speed Limit

- •5.7.3 Extreme Points of a V-n Diagram

- •Positive Loads

- •Negative Loads

- •5.8 Gust Envelope

- •6.1 Overview

- •6.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •6.1.2 Coursework Content

- •6.2 Introduction

- •Closure of the Fuselage

- •6.4 Civil Aircraft Fuselage: Typical Shaping and Layout

- •6.4.1 Narrow-Body, Single-Aisle Aircraft

- •6.4.2 Wide-Body, Double-Aisle Aircraft

- •6.4.3 Worked-Out Example: Civil Aircraft Fuselage Layout

- •6.5.1 Aerofoil Selection

- •6.5.2 Wing Design

- •Planform Shape

- •Wing Reference Area

- •Wing Sweep

- •Wing Twist

- •Wing Dihedral/Anhedral

- •6.5.3 Wing-Mounted Control-Surface Layout

- •6.5.4 Positioning of the Wing Relative to the Fuselage

- •6.6.1 Horizontal Tail

- •6.6.2 Vertical Tail

- •6.8 Undercarriage Positioning

- •6.10 Miscellaneous Considerations in Civil Aircraft

- •6.12.1 Use of Statistics in the Class of Military Trainer Aircraft

- •6.12.3 Miscellaneous Considerations – Military Design

- •6.13 Variant CAS Design

- •6.13.1 Summary of the Worked-Out Military Aircraft Preliminary Details

- •7 Undercarriage

- •7.1 Overview

- •7.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •7.1.2 Coursework Content

- •7.2 Introduction

- •7.3 Types of Undercarriage

- •7.5 Undercarriage Retraction and Stowage

- •7.5.1 Stowage Space Clearances

- •7.6 Undercarriage Design Drivers and Considerations

- •7.7 Turning of an Aircraft

- •7.8 Wheels

- •7.9 Loads on Wheels and Shock Absorbers

- •7.9.1 Load on Wheels

- •7.9.2 Energy Absorbed

- •7.11 Tires

- •7.13 Undercarriage Layout Methodology

- •7.14 Worked-Out Examples

- •7.14.1 Civil Aircraft: Bizjet

- •Baseline Aircraft with 10 Passengers at a 33-Inch Pitch

- •Shrunk Aircraft (Smallest in the Family Variant) with 6 Passengers at a 33-Inch Pitch

- •7.14.2 Military Aircraft: AJT

- •7.15 Miscellaneous Considerations

- •7.16 Undercarriage and Tire Data

- •8 Aircraft Weight and Center of Gravity Estimation

- •8.1 Overview

- •8.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •8.1.2 Coursework Content

- •8.2 Introduction

- •8.3 The Weight Drivers

- •8.4 Aircraft Mass (Weight) Breakdown

- •8.5 Desirable CG Position

- •8.6 Aircraft Component Groups

- •8.6.1 Civil Aircraft

- •8.6.2 Military Aircraft (Combat Category)

- •8.7 Aircraft Component Mass Estimation

- •8.8 Rapid Mass Estimation Method: Civil Aircraft

- •8.9 Graphical Method for Predicting Aircraft Component Weight: Civil Aircraft

- •8.10 Semi-empirical Equation Method (Statistical)

- •8.10.1 Fuselage Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.2 Wing Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.3 Empennage Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.4 Nacelle Group – Civil Aircraft

- •Jet Type (Includes Pylon Mass)

- •Turboprop Type

- •Piston-Engine Nacelle

- •8.10.5 Undercarriage Group – Civil Aircraft

- •Tricycle Type (Retractable) – Fuselage-Mounted (Nose and Main Gear Estimated Together)

- •8.10.6 Miscellaneous Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.7 Power Plant Group – Civil Aircraft

- •Turbofans

- •Turboprops

- •Piston Engines

- •8.10.8 Systems Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.9 Furnishing Group – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.10 Contingency and Miscellaneous – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.11 Crew – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.12 Payload – Civil Aircraft

- •8.10.13 Fuel – Civil Aircraft

- •8.11 Worked-Out Example – Civil Aircraft

- •8.11.1 Fuselage Group Mass

- •8.11.2 Wing Group Mass

- •8.11.3 Empennage Group Mass

- •8.11.4 Nacelle Group Mass

- •8.11.5 Undercarriage Group Mass

- •8.11.6 Miscellaneous Group Mass

- •8.11.7 Power Plant Group Mass

- •8.11.8 Systems Group Mass

- •8.11.9 Furnishing Group Mass

- •8.11.10 Contingency Group Mass

- •8.11.11 Crew Mass

- •8.11.12 Payload Mass

- •8.11.13 Fuel Mass

- •8.11.14 Weight Summary

- •Variant Aircraft in the Family

- •8.12 Center of Gravity Determination

- •8.12.1 Bizjet Aircraft CG Location Example

- •8.12.2 First Iteration to Fine Tune CG Position Relative to Aircraft and Components

- •8.13 Rapid Mass Estimation Method – Military Aircraft

- •8.14 Graphical Method to Predict Aircraft Component Weight – Military Aircraft

- •8.15 Semi-empirical Equation Methods (Statistical) – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.1 Military Aircraft Fuselage Group (SI System)

- •8.15.2 Military Aircraft Wing Mass (SI System)

- •8.15.3 Military Aircraft Empennage

- •8.15.4 Nacelle Mass Example – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.5 Power Plant Group Mass Example – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.6 Undercarriage Mass Example – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.7 System Mass – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.8 Aircraft Furnishing – Military Aircraft

- •8.15.11 Crew Mass

- •8.16.1 AJT Fuselage Example (Based on CAS Variant)

- •8.16.2 AJT Wing Example (Based on CAS Variant)

- •8.16.3 AJT Empennage Example (Based on CAS Variant)

- •8.16.4 AJT Nacelle Mass Example (Based on CAS Variant)

- •8.16.5 AJT Power Plant Group Mass Example (Based on AJT Variant)

- •8.16.6 AJT Undercarriage Mass Example (Based on CAS Variant)

- •8.16.7 AJT Systems Group Mass Example (Based on AJT Variant)

- •8.16.8 AJT Furnishing Group Mass Example (Based on AJT Variant)

- •8.16.9 AJT Contingency Group Mass Example

- •8.16.10 AJT Crew Mass Example

- •8.16.13 Weights Summary – Military Aircraft

- •8.17 CG Position Determination – Military Aircraft

- •8.17.1 Classroom Worked-Out Military AJT CG Location Example

- •8.17.2 First Iteration to Fine Tune CG Position and Components Masses

- •9 Aircraft Drag

- •9.1 Overview

- •9.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •9.1.2 Coursework Content

- •9.2 Introduction

- •9.4 Aircraft Drag Breakdown (Subsonic)

- •9.5 Aircraft Drag Formulation

- •9.6 Aircraft Drag Estimation Methodology (Subsonic)

- •9.7 Minimum Parasite Drag Estimation Methodology

- •9.7.2 Computation of Wetted Areas

- •Lifting Surfaces

- •Fuselage

- •Nacelle

- •9.7.3 Stepwise Approach to Compute Minimum Parasite Drag

- •9.8 Semi-empirical Relations to Estimate Aircraft Component Parasite Drag

- •9.8.1 Fuselage

- •9.8.2 Wing, Empennage, Pylons, and Winglets

- •9.8.3 Nacelle Drag

- •Intake Drag

- •Base Drag

- •Boat-Tail Drag

- •9.8.4 Excrescence Drag

- •9.8.5 Miscellaneous Parasite Drags

- •Air-Conditioning Drag

- •Trim Drag

- •Aerials

- •9.9 Notes on Excrescence Drag Resulting from Surface Imperfections

- •9.10 Minimum Parasite Drag

- •9.12 Subsonic Wave Drag

- •9.13 Total Aircraft Drag

- •9.14 Low-Speed Aircraft Drag at Takeoff and Landing

- •9.14.1 High-Lift Device Drag

- •9.14.2 Dive Brakes and Spoilers Drag

- •9.14.3 Undercarriage Drag

- •9.14.4 One-Engine Inoperative Drag

- •9.15 Propeller-Driven Aircraft Drag

- •9.16 Military Aircraft Drag

- •9.17 Supersonic Drag

- •9.18 Coursework Example: Civil Bizjet Aircraft

- •9.18.1 Geometric and Performance Data

- •Fuselage (see Figure 9.13)

- •Wing (see Figure 9.13)

- •Empennage (see Figure 9.13)

- •Nacelle (see Figure 9.13)

- •9.18.2 Computation of Wetted Areas, Re, and Basic CF

- •Fuselage

- •Wing

- •Empennage (same procedure as for the wing)

- •Nacelle

- •Pylon

- •9.18.3 Computation of 3D and Other Effects to Estimate Component

- •Fuselage

- •Wing

- •Empennage

- •Nacelle

- •Pylon

- •9.18.4 Summary of Parasite Drag

- •9.18.5 CDp Estimation

- •9.18.6 Induced Drag

- •9.18.7 Total Aircraft Drag at LRC

- •9.19 Coursework Example: Subsonic Military Aircraft

- •9.19.1 Geometric and Performance Data of a Vigilante RA-C5 Aircraft

- •Fuselage

- •Wing

- •Empennage

- •9.19.2 Computation of Wetted Areas, Re, and Basic CF

- •Fuselage

- •Wing

- •Empennage (same procedure as for the wing)

- •9.19.3 Computation of 3D and Other Effects to Estimate Component CDpmin

- •Fuselage

- •Wing

- •Empennage

- •9.19.4 Summary of Parasite Drag

- •9.19.5 CDp Estimation

- •9.19.6 Induced Drag

- •9.19.7 Supersonic Drag Estimation

- •9.19.8 Total Aircraft Drag

- •9.20 Concluding Remarks

- •10 Aircraft Power Plant and Integration

- •10.1 Overview

- •10.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •10.1.2 Coursework Content

- •10.2 Background

- •10.4 Introduction: Air-Breathing Aircraft Engine Types

- •10.4.1 Simple Straight-Through Turbojet

- •10.4.2 Turbofan: Bypass Engine

- •10.4.3 Afterburner Engine

- •10.4.4 Turboprop Engine

- •10.4.5 Piston Engine

- •10.6 Formulation and Theory: Isentropic Case

- •10.6.1 Simple Straight-Through Turbojet Engine: Formulation

- •10.6.2 Bypass Turbofan Engine: Formulation

- •10.6.3 Afterburner Engine: Formulation

- •10.6.4 Turboprop Engine: Formulation

- •Summary

- •10.7 Engine Integration with an Aircraft: Installation Effects

- •10.7.1 Subsonic Civil Aircraft Nacelle and Engine Installation

- •10.7.2 Turboprop Integration to Aircraft

- •10.7.3 Combat Aircraft Engine Installation

- •10.8 Intake and Nozzle Design

- •10.8.1 Civil Aircraft Intake Design: Inlet Sizing

- •10.8.2 Military Aircraft Intake Design

- •10.9 Exhaust Nozzle and Thrust Reverser

- •10.9.1 Civil Aircraft Thrust Reverser Application

- •10.9.2 Civil Aircraft Exhaust Nozzles

- •10.9.3 Coursework Example of Civil Aircraft Nacelle Design

- •Intake Geometry (see Section 10.8.1)

- •Lip Section (Crown Cut)

- •Lip Section (Keel Cut)

- •Nozzle Geometry

- •10.9.4 Military Aircraft Thrust Reverser Application and Exhaust Nozzles

- •10.10 Propeller

- •10.10.2 Propeller Theory

- •Momentum Theory: Actuator Disc

- •Blade-Element Theory

- •10.10.3 Propeller Performance: Practical Engineering Applications

- •Static Performance (see Figures 10.34 and 10.36)

- •In-Flight Performance (see Figures 10.35 and 10.37)

- •10.10.5 Propeller Performance at STD Day: Worked-Out Example

- •10.11 Engine-Performance Data

- •Takeoff Rating

- •Maximum Continuous Rating

- •Maximum Climb Rating

- •Maximum Cruise Rating

- •Idle Rating

- •10.11.1 Piston Engine

- •10.11.2 Turboprop Engine (Up to 100 Passengers Class)

- •Takeoff Rating

- •Maximum Climb Rating

- •Maximum Cruise Rating

- •10.11.3 Turbofan Engine: Civil Aircraft

- •Turbofans with a BPR Around 4 (Smaller Engines; e.g., Bizjets)

- •Turbofans with a BPR around 5 or 7 (Larger Engines; e.g., RJs and Larger)

- •10.11.4 Turbofan Engine – Military Aircraft

- •11 Aircraft Sizing, Engine Matching, and Variant Derivative

- •11.1 Overview

- •11.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •11.1.2 Coursework Content

- •11.2 Introduction

- •11.3 Theory

- •11.3.1 Sizing for Takeoff Field Length

- •Civil Aircraft Design: Takeoff

- •Military Aircraft Design: Takeoff

- •11.3.2 Sizing for the Initial Rate of Climb

- •11.3.3 Sizing to Meet Initial Cruise

- •11.3.4 Sizing for Landing Distance

- •11.4 Coursework Exercises: Civil Aircraft Design (Bizjet)

- •11.4.1 Takeoff

- •11.4.2 Initial Climb

- •11.4.3 Cruise

- •11.4.4 Landing

- •11.5 Coursework Exercises: Military Aircraft Design (AJT)

- •11.5.1 Takeoff – Military Aircraft

- •11.5.2 Initial Climb – Military Aircraft

- •11.5.3 Cruise – Military Aircraft

- •11.5.4 Landing – Military Aircraft

- •11.6 Sizing Analysis: Civil Aircraft (Bizjet)

- •11.6.1 Variants in the Family of Aircraft Design

- •11.6.2 Example: Civil Aircraft

- •11.7 Sizing Analysis: Military Aircraft

- •11.7.1 Single-Seat Variant in the Family of Aircraft Design

- •11.8 Sensitivity Study

- •11.9 Future Growth Potential

- •12.1 Overview

- •12.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •12.1.2 Coursework Content

- •12.2 Introduction

- •12.3 Static and Dynamic Stability

- •12.3.1 Longitudinal Stability: Pitch Plane (Pitch Moment, M)

- •12.3.2 Directional Stability: Yaw Plane (Yaw Moment, N)

- •12.3.3 Lateral Stability: Roll Plane (Roll Moment, L)

- •12.3.4 Summary of Forces, Moments, and Their Sign Conventions

- •12.4 Theory

- •12.4.1 Pitch Plane

- •12.4.2 Yaw Plane

- •12.4.3 Roll Plane

- •12.6 Inherent Aircraft Motions as Characteristics of Design

- •12.6.1 Short-Period Oscillation and Phugoid Motion

- •12.6.2 Directional and Lateral Modes of Motion

- •12.7 Spinning

- •12.8 Design Considerations for Stability: Civil Aircraft

- •12.9 Military Aircraft: Nonlinear Effects

- •12.10 Active Control Technology: Fly-by-Wire

- •13 Aircraft Performance

- •13.1 Overview

- •13.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •13.1.2 Coursework Content

- •13.2 Introduction

- •13.2.1 Aircraft Speed

- •13.3 Establish Engine Performance Data

- •13.3.1 Turbofan Engine (BPR < 4)

- •Takeoff Rating (Bizjet): Standard Day

- •Maximum Climb Rating (Bizjet): Standard Day

- •Maximum Cruise Rating (Bizjet): Standard Day

- •13.3.2 Turbofan Engine (BPR > 4)

- •13.3.3 Military Turbofan (Advanced Jet Trainer/CAS Role – Very Low BPR) – STD Day

- •13.3.4 Turboprop Engine Performance

- •Takeoff Rating (Turboprop): Standard Day

- •Maximum Climb Rating (Turboprop): Standard Day

- •Maximum Cruise Rating (Turboprop): Standard Day

- •13.4 Derivation of Pertinent Aircraft Performance Equations

- •13.4.1 Takeoff

- •Balanced Field Length: Civil Aircraft

- •Takeoff Equations

- •13.4.2 Landing Performance

- •13.4.3 Climb and Descent Performance

- •Summary

- •Descent

- •13.4.4 Initial Maximum Cruise Speed

- •13.4.5 Payload Range Capability

- •13.5 Aircraft Performance Substantiation: Worked-Out Examples (Bizjet)

- •13.5.1 Takeoff Field Length (Bizjet)

- •Segment A: All Engines Operating up to the Decision Speed V1

- •Segment B: One-Engine Inoperative Acceleration from V1 to Liftoff Speed, VLO

- •Segment C: Flaring Distance with One Engine Inoperative from VLO to V2

- •Segment E: Braking Distance from VB to Zero Velocity (Flap Settings Are of Minor Consequence)

- •Discussion of the Takeoff Analysis

- •13.5.2 Landing Field Length (Bizjet)

- •13.5.3 Climb Performance Requirements (Bizjet)

- •13.5.4 Integrated Climb Performance (Bizjet)

- •13.5.5 Initial High-Speed Cruise (Bizjet)

- •13.5.7 Descent Performance (Bizjet)

- •13.5.8 Payload Range Capability

- •13.6 Aircraft Performance Substantiation: Military Aircraft (AJT)

- •13.6.2 Takeoff Field Length (AJT)

- •Distance Covered from Zero to the Decision Speed V1

- •Distance Covered from Zero to Liftoff Speed VLO

- •Distance Covered from VLO to V2

- •Total Takeoff Distance

- •Stopping Distance and the CFL

- •Distance Covered from V1 to Braking Speed VB

- •Verifying the Climb Gradient at an 8-Deg Flap

- •13.6.3 Landing Field Length (AJT)

- •13.6.4 Climb Performance Requirements (AJT)

- •13.6.5 Maximum Speed Requirements (AJT)

- •13.6.6 Fuel Requirements (AJT)

- •13.7 Summary

- •13.7.1 The Bizjet

- •14 Computational Fluid Dynamics

- •14.1 Overview

- •14.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •14.1.2 Coursework Content

- •14.2 Introduction

- •14.3 Current Status

- •14.4 Approach to CFD Analyses

- •14.4.1 In the Preprocessor (Menu-Driven)

- •14.4.2 In the Flow Solver (Menu-Driven)

- •14.4.3 In the Postprocessor (Menu-Driven)

- •14.5 Case Studies

- •14.6 Hierarchy of CFD Simulation Methods

- •14.6.1 DNS Simulation Technique

- •14.6.2 Large Eddy Simulation (LES) Technique

- •14.6.3 Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) Technique

- •14.6.4 RANS Equation Technique

- •14.6.5 Euler Method Technique

- •14.6.6 Full-Potential Flow Equations

- •14.6.7 Panel Method

- •14.7 Summary

- •15 Miscellaneous Design Considerations

- •15.1 Overview

- •15.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •15.1.2 Coursework Content

- •15.2 Introduction

- •15.2.1 Environmental Issues

- •15.2.2 Materials and Structures

- •15.2.3 Safety Issues

- •15.2.4 Human Interface

- •15.2.5 Systems Architecture

- •15.2.6 Military Aircraft Survivability Issues

- •15.2.7 Emerging Scenarios

- •15.3 Noise Emissions

- •Approach

- •Sideline

- •15.3.1 Summary

- •15.4 Engine Exhaust Emissions

- •15.5 Aircraft Materials

- •15.5.1 Material Properties

- •15.5.2 Material Selection

- •15.5.3 Coursework Overview

- •Civil Aircraft Design

- •Military Aircraft Design

- •15.6 Aircraft Structural Considerations

- •15.7 Doors: Emergency Egress

- •Coursework Exercise

- •15.8 Aircraft Flight Deck (Cockpit) Layout

- •15.8.1 Multifunctional Display and Electronic Flight Information System

- •15.8.2 Combat Aircraft Flight Deck

- •15.8.3 Civil Aircraft Flight Deck

- •15.8.4 Head-Up Display

- •15.8.5 Helmet-Mounted Display

- •15.8.6 Hands-On Throttle and Stick

- •15.8.7 Voice-Operated Control

- •15.9 Aircraft Systems

- •15.9.1 Aircraft Control Subsystem

- •15.9.2 Engine and Fuel Control Subsystems

- •Piston Engine Fuel Control System (The total system weight is approximately 1 to 1.5% of the MTOW)

- •Turbofan Engine Fuel Control System (The total system weight is approximately 1.5 to 2% of the MTOW)

- •Fuel Storage and Flow Management

- •15.9.3 Emergency Power Supply

- •15.9.4 Avionics Subsystems

- •Military Aircraft Application

- •Civil Aircraft Application

- •15.9.5 Electrical Subsystem

- •15.9.6 Hydraulic Subsystem

- •15.9.7 Pneumatic System

- •ECS: Cabin Pressurization and Air-Conditioning

- •Oxygen Supply

- •Anti-icing, De-icing, Defogging, and Rain-Removal Systems

- •Defogging and Rain-Removal Systems

- •15.9.8 Utility Subsystem

- •15.9.9 End-of-Life Disposal

- •15.10 Military Aircraft Survivability

- •15.10.1 Military Emergency Escape

- •15.10.2 Military Aircraft Stealth Consideration

- •15.11 Emerging Scenarios

- •Counterterrorism Design Implementation

- •Health Issues

- •Damage from Runway Debris

- •16 Aircraft Cost Considerations

- •16.1 Overview

- •16.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •16.1.2 Coursework Content

- •16.2 Introduction

- •16.3 Aircraft Cost and Operational Cost

- •Operating Cost

- •16.4 Aircraft Costing Methodology: Rapid-Cost Model

- •16.4.1 Nacelle Cost Drivers

- •Group 1

- •Group 2

- •16.4.2 Nose Cowl Parts and Subassemblies

- •16.4.3 Methodology (Nose Cowl Only)

- •Cost of Parts Fabrication

- •Subassemblies

- •Cost of Amortization of the NRCs

- •16.4.4 Cost Formulas and Results

- •16.5 Aircraft Direct Operating Cost

- •16.5.1 Formulation to Estimate DOC

- •Aircraft Price

- •Fixed-Cost Elements

- •Trip-Cost Elements

- •16.5.2 Worked-Out Example of DOC: Bizjet

- •Aircraft Price

- •Fixed-Cost Elements

- •Trip-Cost Elements

- •OC of the Variants in the Family

- •17 Aircraft Manufacturing Considerations

- •17.1 Overview

- •17.1.1 What Is to Be Learned?

- •17.1.2 Coursework Content

- •17.2 Introduction

- •17.3 Design for Manufacture and Assembly

- •17.4 Manufacturing Practices

- •17.5 Six Sigma Concept

- •17.6 Tolerance Relaxation at the Wetted Surface

- •17.6.1 Sources of Aircraft Surface Degeneration

- •17.6.2 Cost-versus-Tolerance Relationship

- •17.7 Reliability and Maintainability

- •17.8 Design Considerations

- •17.8.1 Category I: Technology-Driven Design Considerations

- •17.8.2 Category II: Manufacture-Driven Design Considerations

- •17.8.3 Category III: Management-Driven Design Considerations

- •17.8.4 Category IV: Operator-Driven Design Considerations

- •17.9 “Design for Customer”

- •17.9.1 Index for “Design for Customer”

- •17.9.2 Worked-Out Example

- •Standard Parameters of the Baseline Aircraft

- •Parameters of the Extended Variant Aircraft

- •Parameters of the Shortened Variant Aircraft

- •17.10 Digital Manufacturing Process Management

- •Process Detailing and Validation

- •Resource Modeling and Simulation

- •Process Planning and Simulation

- •17.10.1 Product, Process, and Resource Hub

- •17.10.3 Shop-Floor Interface

- •17.10.4 Design for Maintainability and 3D-Based Technical Publication Generation

- •Midrange Aircraft (Airbus 320 class)

- •References

- •ROAD MAP OF THE BOOK

- •CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

- •CHAPTER 3. AERODYNAMIC CONSIDERATIONS

- •CHAPTER 5. AIRCRAFT LOAD

- •CHAPTER 6. CONFIGURING AIRCRAFT

- •CHAPTER 7. UNDERCARRIAGE

- •CHAPTER 8. AIRCRAFT WEIGHT AND CENTER OF GRAVITY ESTIMATION

- •CHAPTER 9. AIRCRAFT DRAG

- •CHAPTER 10. AIRCRAFT POWER PLANT AND INTEGRATION

- •CHAPTER 11. AIRCRAFT SIZING, ENGINE MATCHING, AND VARIANT DERIVATIVE

- •CHAPTER 12. STABILITY CONSIDERATIONS AFFECTING AIRCRAFT CONFIGURATION

- •CHAPTER 13. AIRCRAFT PERFORMANCE

- •CHAPTER 14. COMPUTATIONAL FLUID DYNAMICS

- •CHAPTER 15. MISCELLANEOUS DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

- •CHAPTER 16. AIRCRAFT COST CONSIDERATIONS

- •CHAPTER 17. AIRCRAFT MANUFACTURING CONSIDERATIONS

- •Index

446 |

Aircraft Performance |

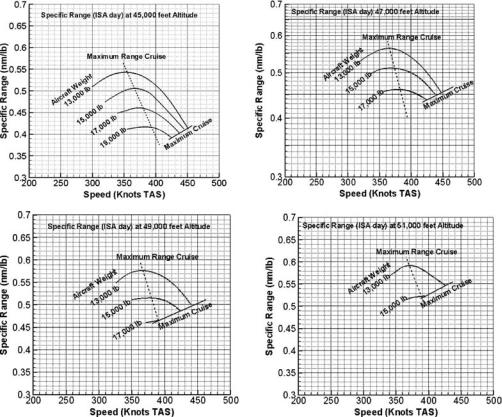

Figure 13.14. Specific range of a Bizjet

performances of fuel consumed, distance covered, and time taken to climb at the desired altitude.

13.5.5 Initial High-Speed Cruise (Bizjet)

An aircraft at the initial HSC is at Mach 0.74 (i.e., 716.4 ft/s) at a 41,000-ft altitude (ρ = 0.00055 slug/ft3). The fuel burned to climb is computed (but not shown) as 700 lb. The aircraft weight at initial cruise is 20,000 lb. At Mach 0.74, the aircraft lift coefficient CL = MTOM/qSW = 20,000/(0.5 × 0.00055 × 716.42 × 323) = 20,000/45,627 = 0.438.

The clean aircraft drag coefficient from Figure 9.2 at CL = 0.438 gives CDclean = 0.0324. The clean aircraft drag, D = 0.0324 × (0.5 × 0.00055 × 716.42 × 323) = 0.0324 × 45,627 = 1,478 lb.

The available all-engines-installed thrust at maximum cruise rating at the speed and altitude from Figure 13.3 at Mach 0.74 is T = 2 × 790 = 1,580 lb (adequate). The capability satisfies the market requirement of Mach 0.74 at HSC.

13.5.6 Specific Range (Bizjet)

Specific range is a convenient way to present cruise performance. Using Equation 13.27, the Sp.Rn is computed. The details of the specific range are not a direct

13.5 Aircraft Performance Substantiation: Worked-Out Examples (Bizjet) |

447 |

substantiation requirement; it is needed to compute the cruise-segment performances (i.e., fuel burned, distance covered, and time taken). Figure 13.14 shows the specific range for the Bizjet (i.e., the worked-out example). When readers redo the specific-range computations, there may be minor differences in the results. From the Sp. Rn values, the fuel burned and distance covered is worked out, which in turn gives the time taken for the distance.

13.5.7 Descent Performance (Bizjet)

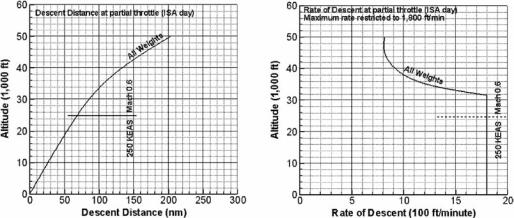

It is also explained in Section 13.1 that only results of the integrated descent performance in graphical form are provided, as shown in Figures 13.16 through 13.18. It is convenient to establish first the descent velocity schedule (Figure 13.16) and the point performances of the rate of descent (Figure 13.17) down to sea level (this is valid for all weights; the difference between the weights is ignored). When readers redo the calculations, there may be minor differences in the results.

The related governing equations are explained in Section 13.4.3, which also mentions that the descent rate is restricted by the rate of the cabin-pressurization schedule to ensure passenger comfort. Two difficulties in computing the descent performance are the partial-throttle engine performance and the ECS pressurization capabilities, which dictate the rate of descent that, in turn, stipulates the descent velocity schedule (these are not provided in this book). Instructors may assist in establishing these two graphs, which – in the absence of any information – may be used. The following simplifications are useful.

The first simplification is in obtaining the partial-throttle engine performance, as follows:

1.The zero thrust at idle rpm is at about 40% of the maximum rated power/ thrust.

2.The maximum cruise rating is taken at 85% of the maximum rated power/ thrust.

3.The descent is carried out from 40 to 60% of the maximum cruise rating.

The second simplification is provision of the descent velocity schedule for the ECS capability.

In the industry, the exact installed-engine performance at each partial-throttle condition is computed from the engine deck supplied by the manufacturer. Also, the ECS manufacturer supplies the cabin-pressurization capability, from which aircraft designers work out the velocity schedule.

The inside cabin pressurization is restricted to the equivalent rate of 300 ft/min at sea level to ensure passenger comfort. An aircraft’s rate of descent is then limited to the pneumatic capability of the ECS. A Bizjet is restricted to a maximum of 1,800 ft/min at any time (for a higher performance at lower altitudes, it can be increased to 2,500 ft/min). The descent speed schedule continues at Mach 0.6 from the cruise altitude until it reaches the approach height, when it then changes to a constant VEAS = 250 knots until the end (for a higher performance, it can be increased to Mach 0.7 and VEAS = 300 knots). The longest ranges can be achieved at the minimum rate of descent; this requires a throttle-dependent descent to stay within the various limits.

448 |

Aircraft Performance |

(a) Descent Speed Schedule |

(b) Rate of Descent |

Figure 13.15. Descent point performance

It is convenient to establish first the point performances of the velocity schedule (Figure 13.15a) and the rate of descent (Figure 13.15b is for all weights; the variation is minor). The descent is performed within the limits of the passenger comfort level. However, in an emergency, a rapid descent is necessary to compensate for the loss of pressure and for oxygen recovery.

An integrated descent performance is computed in the same way as the climb performance; that is, it is computed in steps of approximate 5,000-ft altitudes (or as convenient) in which the variables are kept invariant. (Computation work is not shown herein.)

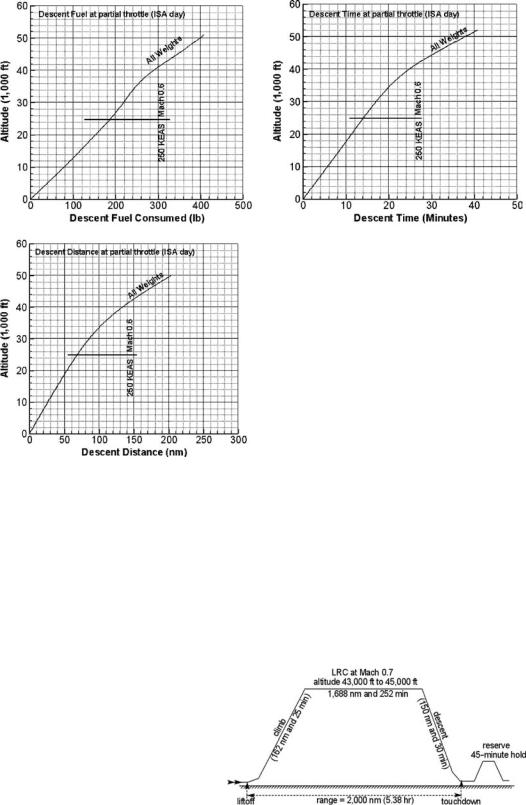

Figure 13.16 plots fuel consumed, time taken, and distance covered during the descent from the ceiling altitude to sea level. When readers redo the integrated descent performances, there may be minor differences in the results.

13.5.8 Payload Range Capability

A typical transport aircraft mission profile is shown in Figure 13.17. Equations 13.14 through 13.18 give the mission range and fuel consumption expressions as follows:

mission range = climb distance(Rclimb) + cruise distance(Rcruise)

+ landing distance(Rdescent )

where Rclimb = sclimb and Rdescent = sdescent are computed from the altitude increments.

mission fuel = climb fuel (Fuelclimb) + cruise fuel(Fuelcruise)

+ descent fuel(Fueldescent )

where Fuelclimb = fuelclimb and Fueldescent = fueldescent are computed from the altitude increments.

The minimum reserve fuel is computed for an aircraft maintaining a 5,000-ft altitude from Mach 0.35 to Mach 0.4 at about 60% of the maximum rating for

13.5 Aircraft Performance Substantiation: Worked-Out Examples (Bizjet) |

449 |

Figure 13.16. Integrated descent performance for a Bizjet

45 minutes or a 100 nm diversion cruising at Mach 0.5 and at a 25,000-ft altitude plus 20 minutes. The amount of reserve fuel must be decided by the operator and be suitable for the region of operation. The worked-out example uses the first option.

Fuel is consumed during taxiing, takeoff, and landing without any range contribution; this fuel is added to the mission fuel and the total is known as block fuel. The time taken from the start and stop of the engine at the beginning and the end of the mission is known as block time, in which a small part of time is not contributing to the gain in range. The additional fuel burn and time consumed without contributing

Figure 13.17. Transport-aircraft mission profile

450 |

|

|

|

Aircraft Performance |

|

Table 13.18. Bizjet range |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aircraft |

|

|

|

|

|

weight (lb) |

Distance (nm) |

Fuel (lb) |

Time (min) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Start and taxi out |

20,723 |

0 |

100 |

3 |

|

Takeoff to 1,500 ft |

20,623 |

0 |

123 |

5 |

|

Climb to 43,000 ft |

20,500 |

162 |

800 |

25 |

|

|

Initial cruise at 43,000 ft |

19,700 |

|

|

|

|

End cruise at 45,000 ft |

16,240 |

1,688 |

3,460 |

252 |

|

Descent to 1,500 ft |

15,900 |

150 |

340 |

30 |

|

Approach and land |

15,800 |

0 |

100 |

5 |

Taxi in (from reserve) |

|

0 |

20 |

3 |

|

Stage Total |

|

2,000 |

4,923 |

323 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(5.38 hrs) |

From operational statistics.

to range are shown in Table 13.17, taken from operational statistics. The descent fuel is estimated at 300 lb and the end cruise weight is computed as Wend cruise = 12,760 + 2,420 + 650 + 300 = 16,280 lb. This is then iterated to correct the descent fuel in the final form, as shown in Table 13.17.

The cruise altitude of a Bizjet starts at 43,000 ft and ends at 45,000 ft (the design range is long in order to make an incremental cruise). The average value of cruising at 44,000 ft (ρ = 0.00048 slug/ft3) is used. The methods to compute Rclimb and Rdescent are discussed in Section 13.4.3. Using Figures 13.11 through 13.13, the required values are given as Rclimb = 162 nm, Fuelclimb = 800 lb, and Timeclimb = 25 min, and Rdescent = 150 nm, Fueldescent = 340 lbs, and Timedescent = 30 min (in a partial-throttle, gliding descent). Table 13.18 displays the aircraft weight at each segment of the mission profile. The aircraft is at the LRC schedule operating at Mach 0.7 (OEW = 12,760 lb and payload = 2,420 lb).

For reserve fuel, at a 5,000-ft altitude (ρ = 0.00204 lb/ft3) and Mach 0.35 (384 ft/s) gives CL = 0.323, resulting in CD = 0.025 (see Figure 9.2). Equating thrust to drag, T/engine = 610 lb with sfc = 0.7 lb/hr/lb. For 45 minutes of holding, fuel consumed = 2 × 0.75 × 0.7 × 610 = 640 lbs. For safety, 800 lbs is used (operators can opt for higher reserves than the minimum requirement).

An aircraft must carry a reserve fuel for 45 minutes of holding and/or diversion around a landing airfield, which amounts to 600 lb. The range performance can be improved with a gradual climb from 43,000 to 47,000 ft as the aircraft becomes lighter with fuel consumed. From Table 13.18, the midcruise weight is (19,700 + 16,240)/2 = 17,970 lbs.

The LRC is at Mach 0.7 (677.7 ft/s). The engine-power setting is below the maximum cruise rating. The aircraft lift coefficient, CL = 17,970/(0.5 × 0.00046 × 677.72 × 323) = 17,970/34,120 = 0.527. From Figure 9.2, the clean aircraft drag coefficient, CD = 0.033. The aircraft drag, D = 0.033 × (0.5 × 0.00046 × 677.72 × 323) = 0.033 × 34,120 = 1,126 lb.

Therefore, the thrust required per engine is 1,126/2 = 563 lbs. Figure 13.3 shows the available thrust of 620 lb per engine at the maximum cruise rating meant for HSC; that is, it allows throttling back for the LRC speed. The sfc is not much affected by the throttling back to the cruise rating. From Figure 10.6, the sfc at the