- •About the Author

- •Dedication

- •Author’s Acknowledgments

- •Contents at a Glance

- •Table of Contents

- •Introduction

- •About This Book

- •Conventions Used in This Book

- •How This Book Is Organized

- •Icons Used In This Book

- •Where To Go From Here

- •Understanding Sociology

- •Seeing the World as a Sociologist

- •Social Organization

- •Sociology and Your Life

- •Sociology for Dummies, for Dummies

- •Figuring Out What Sociology Is

- •Discovering Where Sociology Is “Done”

- •So . . . Who Cares about History?

- •The Development of “Sociology”

- •Sociology’s Power Trio

- •Sociology in the 20th Century

- •Sociology Today

- •The Steps of Sociological Research

- •Choosing a Method

- •Analyzing Analytical Tools

- •Preparing For Potential Pitfalls

- •Studying Culture: Makin’ It and Takin’ It

- •Paddling the “Mainstream”

- •Rational — and Irrational — Choices

- •Symbolic Interactionism: Life is a Stage

- •The Strength of Weak Ties

- •Insights from Network Analysis

- •Excavating the Social Strata

- •The Many Means of Inequality

- •Race and Ethnicity

- •Sex and Gender

- •Understanding Religion in History

- •Religion in Theory . . . and in Practice

- •Faith and Freedom in the World Today

- •Criminals in Society

- •The Social Construction of Crime

- •Becoming Deviant

- •Fighting Crime

- •The Corporate Conundrum: Making a Profit Isn’t as Easy — or as Simple — as it Sounds

- •Weber’s Big Idea About Organizations

- •Rational Systems: Bureaucracy at its Purest

- •Natural Systems: We’re Only Human

- •Social Movements: Working for Change

- •Sociology in the City

- •Changing Neighborhoods

- •Life in the City: Perils and Promise

- •The Social Construction of Age

- •Running the Course of Life

- •Taking Care: Health Care and Society

- •Families Past and Present

- •Why Societies Change

- •What Comes Next?

- •Sociology in the Future

- •Randall Collins: Sociological Insight

- •Elijah Anderson: Streetwise

- •Arlie Hochschild: The Second Shift

- •Think Critically About Claims That “Research Proves” One Thing or Another

- •Be Smart About Relationship-Building

- •Learn How to Mobilize a Social Movement

- •Run Your Company Effectively

- •With Hard Work and Determination, Anyone Can Get What They Deserve

- •Our Actions Reflect Our Values

- •We’re Being Brainwashed by the Media

- •Understanding Society is Just a Matter of “Common Sense”

- •Race Doesn’t Matter Any More

- •In Time, Immigrant Families Will Assimilate and Adopt a New Culture

- •Bureaucracy is Dehumanizing

- •People Who Make Bad Choices Are Just Getting the Wrong Messages

- •Index

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 129

Political lobbyists: connecting legislators and groups who want to influence them. (This is why so many former legislators become lobbyists — they’re essentially selling their personal connections to sitting legislators.)

People in all these professions, and many more, earn a lot of their salary simply by knowing people who have an interest in knowing one another — or at least knowing about one another. You pay them to bridge network holes that you want to cross.

This principle of filling structural holes doesn’t only work in business, though — it works in personal life as well. Say you’re a teenager looking for a party. There are probably one or two parties this weekend that a lot of people at your school are going to — but that’s also probably true of every other school in town.

To find the best parties, you’d rather have five acquaintances at five different schools than ten close friends at your own school.

Insights from Network Analysis

Now you have a basic sense of what network analysis is and how it works. The connections among people in a social group form a structure, along which information and influence can be traced. How does thinking about society in this way change the way sociologists think about social life? What specific insights has this approach yielded?

In this section, I explain how network analysis has changed the way sociologists think about the spread of behaviors and the spread of information, and concludes with a discussion of sites like Facebook and MySpace that make social networks visible — to the endless fascination of their millions of users.

The difference between “your society” and your society

Network analysis has been an important tool for sociologists in recent decades because it opens up a whole world of inquiry that didn’t previously exist. Before network analysis became widely used, there were two main ways of studying society.

Top-down, or macrosociological, analysis is the study of social groups considered as entire units. For example, Karl Marx’s argument about the historical rise of capitalism and Max Weber’s argument about increasing rationalization across all of society are macrosociological arguments. When Emile Durkheim said sociologists needed to focus on “social facts,” he was saying that they should pay attention to the big picture rather than individuals in society. (See Chapter 3 for more on these ideas.)

130 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

Bottom-up, or microsociological, analysis is the study of individuals in their social worlds. The Chicago School studies of people from different groups interacting on the street were studies in microsociology, and when Erving Goffman wrote about the different “masks” we wear in different social contexts, that was a microsociological argument. (See Chapter 6 for more on microsociology.)

Network analysis allows sociologists to focus on the connective tissue between individuals and society. To talk about “your society” is to say that there’s some social group that you are “a member of” and are somehow influenced by. That’s pretty vague! Where does this influence come from? Do you somehow inhale it, or get psychic vibes from the fifth dimension?

It’s true that there are some forms of social influence that affect people across an entire society (for example, mass media), but the most important influence comes from the people you know personally and directly encounter. In this way, network analysis helps sociologists appreciate that your actual society — that is, the people you actually interact with and are influenced by — can be quite different than “your society.”

Here’s an example of how this insight has been put into practice. It’s wellknown that obesity is a growing problem in the United States, and for obvious reasons, medical professionals would like to know why. There are a couple of society-wide (no pun intended) culprits that are probably involved: Unhealthy food is becoming ever cheaper and more available relative to healthy food, and advertising campaigns for unhealthy food downplay the risk of obesity. Still, can those factors entirely explain the rise in obesity? Why is the risk especially high among certain groups?

Nicholas Christakis, a sociologist who’s also a physician, worked with network analysis expert James Fowler to study the spread of obesity in a Massachusetts town over three decades. Christakis and Fowler discovered that obesity could be observed to spread through social networks. In effect, it seems, you can “catch” obesity by befriending people who are overweight. As more and more people become overweight, obesity spreads through their networks to become a growing epidemic.

What the researchers’ obesity study (among other network studies over many years) has proved is that social networks can be conduits for the spread of everything from information to influence to behavior, influencing people’s lives at every level. If you’re trying to stay fit, it doesn’t help that your grocery store will sell you a box of cookies for less than the price of an apple, that you see ads everywhere for unhealthy foods, or that your job probably involves you sitting still at a desk for eight hours a day — but what’s really devastating is when the people around you are practicing unhealthy behaviors, overeating, and under-exercising. That makes it seem normal and, in fact, good for you to do the same thing.

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 131

Think about the implications of this finding for other important behaviors that might be socially influenced:

Drug use: Do your friends abuse drugs, or do they stay clear of dangerous substances?

Sexual health: Do your friends have casual sex — and if they do, do they use protection?

Economic stability: Do your friends gamble? Do they make risky investments? Do they max out their credit cards?

Study habits: Do your friends devote time and attention to their schoolwork, or do they blow it off?

These are just a few examples of potentially hazardous behaviors that are probably spread through social networks.

The significance of social networks in this respect is in some respects an inconvenient truth. If there were one or two factors that caused a social problem by affecting everyone equally, the problem could be solved by taking those factors away. If a problem is spread through social networks, though, you’d have to cut the network off to keep the problem from spreading — like digging a trench around a forest fire. Not only is that unethical, it’s probably impossible.

It’s also important to remember, though, that just because one person — or even many people — you’re connected to behaves a certain way, you’ll automatically “get the message” and act on it. You may be getting different messages from different people.

In a study of teenagers in Boston, sociologist David Harding found that it was true that teens who made risky decisions were getting messages consistent with those decisions — for example, their friends might be telling them that staying in school wasn’t worth it — but they were also often getting “the right messages” from their teachers, their parents, and even many of their friends, who encouraged them to graduate and get jobs or go to college.

The problem wasn’t that troubled teens were getting only “the wrong messages.” The problem was that they were getting mixed messages, giving them different scripts to follow (as Goffman might say) in challenging situations. Sometimes they chose the “wrong” script — have risky sex, drop out of school — and sometimes they chose the “right” script. Kids who weren’t getting those mixed signals had a much easier time sticking to one course of action.

Harding’s study wasn’t a study of social networks in the technical sense, but it did incorporate the basic insight of network analysis: that our social connections are important influences on our behavior. What happens when our social connections send us mixed signals? It’s an empirical question that sociologists conducting network analyses may be paying a lot more attention to in the future.

132 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

Opening the channels of communication

If information and influence spread through social networks, is there a way to spread messages more efficiently?

In the great sociologist Emile Durkheim’s classic study of suicide (see Chapter 3), he basically took for granted that all members of a given society shared a set of norms and values. If you live in a Protestant-majority society, then he assumed that you probably have Protestant-majority values.

Durkheim has been criticized for committing the ecological fallacy, which is to assume that because something is true of a system it’s true of all that system’s members. Durkheim observed that Protestant-majority countries had higher suicide rates than Catholic-majority countries, which he took to mean that Protestants were more likely than Catholics to commit suicide. But those data didn’t actually tell him that: How did he know that it wasn’t the minoritygroup Catholics committing suicide — maybe as a result of persecution by the majority-group Protestants? He didn’t. He just assumed, and he may have assumed incorrectly. (We’ll never know.) Durkheim’s study remains an influential landmark in sociology, but a sociologist today would be much less likely to make that kind of assumption.

The German sociologist Georg Simmel, whose most important work came shortly after Durkheim’s, was a big influence on microsociology and has come to be regarded as one of the fathers of network analysis. Simmel focused closely on individual interaction and argued that there are different forms of social interaction, with different rules and norms and through which different types of information are spread.

The moral for those with a message to spread is that it may be a waste of energy to try to broadcast it over an entire social group. What you want to do is make sure your message is heard — and passed on — by the right people in the right settings.

This implication of network analysis has been appreciated not only by sociologists studying the spread of ideas and behavior (see previous section), but by marketers looking to sell their products. Here are some marketing strategies you’ve probably come across; each is inspired by the idea of society as a network:

Distributing free samples of products. If you play a free CD and enjoy it, you may play it for your friends and introduce them to the artist as well.

Sponsoring events where influential people are likely to gather. Many companies sponsor parties or concerts for young people, in the belief that young people can influence older people to use a product — but not vice-versa.

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 133

Using social media (for example, networking tools such as Facebook or Twitter) to encourage individuals to willingly spread marketing messages. Distributing — often online — a video, song, or game that

advertises your product but is also entertaining enough that it might be willingly passed on to friends is a practice called “viral marketing.”

These techniques can obviously be used to make profits, but they’ve also become popular with nonprofit organizations promoting health, environmental awareness, charity, and other good causes. Going through social networks is often an extremely effective way to spread a message, and both sociologists and marketers have taken note.

In journalist Malcolm Gladwell’s popular book The Tipping Point, he writes about the phenomenon by which an idea or behavior (like, say, wearing Hush Puppy loafers) quickly goes from being relatively rare to being wildly popular. Gladwell argues that a few key types of people — people he refers to as mavens, salesmen, and connectors — need to get hold of an idea and help to spread it.

Gladwell’s book isn’t a sociological study, and he provides only examples (rather than systematically analyzed data) to make his point, but sociologists have read and appreciated Gladwell’s book for its compelling argument that social networks are profoundly important in the spread of everything from clothing fads to musical tastes to business practices.

Gladwell’s idea of a “connector” is similar to Ronald Burt’s idea of a person filling a structural hole (discussed earlier in this chapter). A connector is a person who knows many different people from many different groups, so

they are in a position to spread ideas or trends from one group to the other.

Just as biological epidemics caused by dangerous viruses can spread by way of people who move freely from one group to the next, so can social epidemics spread through social connectors — people who can “catch” an idea in one group and then spread it to the next group. When an idea or behavior spreads to multiple different social groups, it’s become a social epidemic. This may be a good thing or a bad thing — depending on, say, whether you think Hush Puppies are attractive shoes — but it is the way the social world works.

Social networking online: Making the invisible visible

If you’re a member of a social networking site like Facebook or MySpace, you’ve probably thought about it multiple times while reading this chapter — and, in fact, while reading this entire book. Social networking sites are a subject of fascination for sociologists and for just about everyone who participates on them.

134 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

These sites normally allow each user to create an online profile, which they can then link to their friends’ profiles. The result is a visible display of something that’s normally invisible: a social network. These sites’ incredible draw — they now involve hundreds of millions of users around the world — is evidence of how important social networks are in people’s lives.

Next time you’re on your favorite social networking site — whichever it may be — consider how people’s behavior on the site illustrates these sociological ideas.

The presentation of self

As I describe in Chapter 6, sociologists observe how we play roles in society — like actors on a stage, as Erving Goffman would put it. A user’s profile is a perfect example of this. Unlike in face-to-face interaction, a user has perfect control over the “face” they present on a social networking site. They can choose which pictures to display, what information to divulge, and which acquaintances to acknowledge.

A lot of the most stressful moments on social networking sites come from tension and cracks in this careful presentation of self. A friend might post something on your profile that you would prefer not be visible, your mom might post an embarrassing photo from when you were an awkward teenager, or your boss may see pictures of you doing something, oh . . . let’s just say unprofessional. All of these things get in the way of your attempt to filter the information about you that is known by the world.

The diversity of social ties

Social networking sites clearly demonstrate a principle that network sociologists have been trying for decades to grapple with: There are as many different kinds of relationships as there are pairs of people in the world, and no matter how many different options a networking site offers you, there will be a lot of relationships that are awkward to manage.

On Facebook, for example, as of this writing you can be a “fan” of a public figure, can specify that you’re a son or daughter or mother or father of one of your family members, and can be in one of several flavors of involvement (“In a relationship,” “Engaged,” “Married,” “It’s complicated”) with one significant other — but beyond that, everyone you’re connected to is just a “friend.” So your “friends” might include:

Your best friend

Your boss

Your grandpa

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 135

Someone you have a huge crush on

Your ex-boyfriend

Your ex-boyfriend’s sister

Your best friend from kindergarten who you haven’t talked to in 15 years

In reality you have very different relationships with all those people, but on Facebook they’re all your “friends.” If a distant relative keeps making inappropriate comments on your profile, you’re going to have to confront her or de-friend her. You can’t publicly note that your relationship to her is not “friend” but rather “crazy second cousin once removed.”

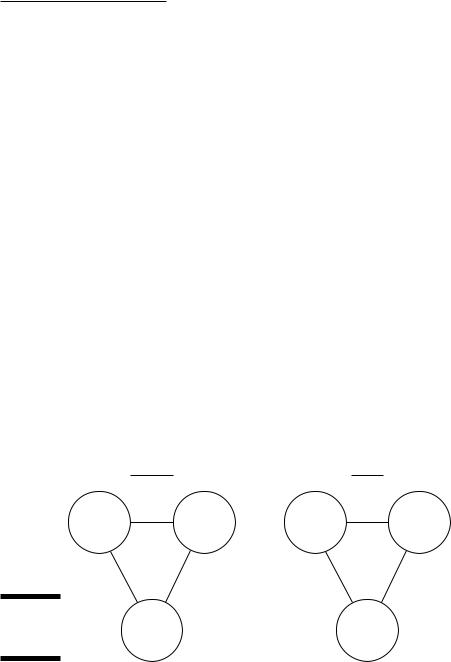

The transitivity of social ties

“Transitivity” is a technical word that basically means “transferability.” In other words, if you have a close social tie, your other close friends are

liable to “catch” that tie. Mark Granovetter writes about what he calls “the forbidden triad” — a situation where one person has close ties to each of two other people, who don’t know one another. (See Figure 7-3.) He calls it “forbidden” not because it’s actually forbidden, but because it’s just so unlikely to happen.

Social networking sites can speed the “healing” of forbidden triads. If you have two good friends who both often comment on your profile, they’re apt to come to know one another and even start a conversation — maybe about you! If that feels weird . . . well, maybe it’s your own fault for not introducing your friends to one another.

|

Unlikely |

|

Likely |

Lydia |

Erik |

Lydia |

Erik |

|

No |

|

friends |

|

connection |

|

|

Good |

Good |

Good |

Good |

friends |

friends |

friends |

friends |

Figure 7-3: |

|

|

|

A forbidden |

Issa |

|

Issa |

triad. |

|

|

|

136 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

The spread of information through social networks

As if gossip didn’t spread quickly enough before the Internet, it spreads like wildfire now. If one of your friends posts a picture of you making out with someone you met at a party, all your friends will know about it, more or less immediately. This is true of other information as well, including information on breaking national and international news, information about funny videos, and even false information about supposed scams and other urban legends.

The principle that most information spreads most efficiently and effectively through social networks was true before the development of the Internet; although the Internet has made it theoretically easier to broadcast something to a mass audience (everyone in the world could read your personal blog right now if they wanted to), it’s also made social networks more important because it’s increased the efficiency of spreading information through them. People still trade information over the backyard fence and around the water cooler, as they always have, but now the backyard fence and the water cooler are online, and you don’t need to wait until you’re thirsty to get the latest scoop. All you have to do is log on.

Online friendships: Trading quality for quantity?

As technologies such as cell phones, laptops, and wireless networks have proliferated, many people have voiced concerns about the effect those technologies are having on “real world” relationships. Ever since the telephone was invented, people have been concerned that technologies that make it easier to connect with people far away will distract from people’s relationships with others who are nearby.

Although it may seem like your little brother is always chatting online and never wants to talk with his actual family, the fact of the matter is that he probably wouldn’t be much more enthused about talking with his family even if the alternative was sitting out on the stoop and watching traffic go by. Historical and sociological evidence from the past century suggests that as technology makes communication easier, what happens is that there’s simply more communication . . . with everyone.

Think about your own life. Who do you talk with most on the phone, trade the most texts with, chat with most online, and trade the most Facebook wall posts with? Chances are, it’s your girlfriend or roommate or best buddy: someone you often see in person. You probably also communicate quite often with people far away, and you probably do a lot more of that than people did before the development of cell phones and the Internet — but that doesn’t necessarily mean you’re neglecting your close relationships with people you actually encounter in person on a daily basis. You’re probably just supplementing them with far-flung friends.

Sociologists and psychologists are still gathering data on how social networking sites and related technologies affect people’s relationships, rather than merely reflecting them . . . but in general, people seem to use those technologies to grow closer to a wide range of people they value. It’s not an either/or proposition.

Part III

Equality and

Inequality in Our

Diverse World

In this part . . .

Any society is made up of many parts — and which “part” you belong to isn’t always obvious. Do I

belong to the middle-class part of American society? The white part? The male part? The Catholic part? The lawabiding part? In this section, I explain how sociologists understand the lines that divide a society.

Chapter 8

Social Stratification:

We’re All Equal, But Some of Us

Are More Equal Than Others

In This Chapter

Excavating the social strata

Understanding the many means of inequality

Climbing up and falling down

The title of this chapter refers to George Orwell’s Animal Farm, a novel that is an allegory meant to show how difficult it is to create a society where everyone’s truly equal. In the book, animals in a barnyard drive the

farmer out and try to create a social order where all animals are equal. Eventually, the pigs start taking advantage of their leadership position and justify their special privileges by the dictum: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

The story rings true because no society, ever, has been completely equal. Social inequality is a topic at the heart of sociology, and in this chapter I explain why.

First, I explain how sociologists think, in general, about inequality — and why it may be a necessary feature of society. Next, I go through the many different means of inequality: all the different ways people manage to draw social boundaries that privilege some at the expense of others. Finally, I look at how inequality changes over time — both for individuals (social mobility) and for entire societies.