- •About the Author

- •Dedication

- •Author’s Acknowledgments

- •Contents at a Glance

- •Table of Contents

- •Introduction

- •About This Book

- •Conventions Used in This Book

- •How This Book Is Organized

- •Icons Used In This Book

- •Where To Go From Here

- •Understanding Sociology

- •Seeing the World as a Sociologist

- •Social Organization

- •Sociology and Your Life

- •Sociology for Dummies, for Dummies

- •Figuring Out What Sociology Is

- •Discovering Where Sociology Is “Done”

- •So . . . Who Cares about History?

- •The Development of “Sociology”

- •Sociology’s Power Trio

- •Sociology in the 20th Century

- •Sociology Today

- •The Steps of Sociological Research

- •Choosing a Method

- •Analyzing Analytical Tools

- •Preparing For Potential Pitfalls

- •Studying Culture: Makin’ It and Takin’ It

- •Paddling the “Mainstream”

- •Rational — and Irrational — Choices

- •Symbolic Interactionism: Life is a Stage

- •The Strength of Weak Ties

- •Insights from Network Analysis

- •Excavating the Social Strata

- •The Many Means of Inequality

- •Race and Ethnicity

- •Sex and Gender

- •Understanding Religion in History

- •Religion in Theory . . . and in Practice

- •Faith and Freedom in the World Today

- •Criminals in Society

- •The Social Construction of Crime

- •Becoming Deviant

- •Fighting Crime

- •The Corporate Conundrum: Making a Profit Isn’t as Easy — or as Simple — as it Sounds

- •Weber’s Big Idea About Organizations

- •Rational Systems: Bureaucracy at its Purest

- •Natural Systems: We’re Only Human

- •Social Movements: Working for Change

- •Sociology in the City

- •Changing Neighborhoods

- •Life in the City: Perils and Promise

- •The Social Construction of Age

- •Running the Course of Life

- •Taking Care: Health Care and Society

- •Families Past and Present

- •Why Societies Change

- •What Comes Next?

- •Sociology in the Future

- •Randall Collins: Sociological Insight

- •Elijah Anderson: Streetwise

- •Arlie Hochschild: The Second Shift

- •Think Critically About Claims That “Research Proves” One Thing or Another

- •Be Smart About Relationship-Building

- •Learn How to Mobilize a Social Movement

- •Run Your Company Effectively

- •With Hard Work and Determination, Anyone Can Get What They Deserve

- •Our Actions Reflect Our Values

- •We’re Being Brainwashed by the Media

- •Understanding Society is Just a Matter of “Common Sense”

- •Race Doesn’t Matter Any More

- •In Time, Immigrant Families Will Assimilate and Adopt a New Culture

- •Bureaucracy is Dehumanizing

- •People Who Make Bad Choices Are Just Getting the Wrong Messages

- •Index

114 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

Brother, can you spare a yam?

The yam exchanges of the Trobriand Islanders of the South Pacific, famously studied by anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, have become a classic example of how gift giving can knit a society together. At certain times, with great ceremony, men present their sisters and daughters with gifts of yams. The yams are stored in ceremonial yam houses, where they are preserved as symbols of social connection — in fact, the yams generally sit there until they rot because families will grow their own yams rather than eat the yams so generously presented to them by their relatives.

In other words, among the Trobrianders, a ceremonial gift of yams is purely a gift given for the sake of giving, in a ceremonial exchange that is virtually mandatory. It’s a gift in the sense that it’s not a payment for service, and it’s altruistic in the sense that you’re giving away actual yams that you could otherwise have eaten —

but though you know that the yams probably aren’t actually going to be eaten, you’d better not keep them for yourself or you’ll face serious social disapproval and life will become quite unpleasant.

So why, then, the yam exchange? Isn’t it just a big waste of food? Regardless of how it came about, the yam exchange serves to make social ties visible and to remind everyone of their obligations to one another. Sometimes a gift is a gift of genuine value outside the exchange (like that $50 check you got for graduation), and other times a gift is just a gift (like that weird little ceramic figurine you also got). They both have a lot of importance in our society, and that’s why your mother told you to say “thank you” for all your gifts. (Though unless you’re a Trobriander exchanging yams, it’s probably most appropriate to say “thank you” and “you’re welcome” with words rather than ceremonial hip thrusts.)

Symbolic Interactionism: Life is a Stage

Symbolic interactionism is the term used to describe the study of individual human interaction in its social context. The word “symbolic” refers to the fact that as people interact with one another in society, they use a range of signs and symbols that have particular meanings in that society — everything from words to gestures to styles of dress. The fact that people don’t always agree on the meanings of particular symbols makes life interesting, as each person tries to achieve their social goals by using the symbols to their advantage. Life is a stage, and each person may play a number of different characters.

That sounds complicated . . . and it is! The basic ideas behind the sociological study of individual interaction are not complicated, though. In the remainder of this chapter I explain how microsociologists understand individual interaction, what they pay attention to when they observe humans interacting face to face.

Chapter 6: Microsociology: If Life Is a Game, What Are the Rules? 115

When you, or anyone else, use words, clothes, or other symbols to communicate, you know (or you should know) to take into consideration that different people will interpret them in different ways. A musician whose lyrics include a lot of profanity knows full well that the songs will offend some listeners and excite others.

Play ball! The rules of the game

As I explain in Chapter 3, microsociology was largely developed by early American sociologists, especially those in the Chicago School. They looked at people interacting in the busy, diverse metropolis and came up with some important ideas about how people negotiate complex social situations.

One of the most important thinkers in this tradition was George Herbert Mead, a Chicago philosopher who influenced many sociologists. Mead pointed out that social life is like a game, and argued that organized game playing among children was a crucial part of their socialization. (For more on socialization, see Chapter 5.)

In a baseball game, for example, there are several different positions — each with its own responsibilities and limits. Each position has a defined goal, which can be accomplished only through certain means. The batter’s goal is to get the ball way into the outfield, ideally over the outfield wall; but they can’t just grab the ball out of the catcher’s mitt and run it out there, they have to hit it with the bat. Similarly, the pitcher’s job is to keep the batter from hitting the ball, but the pitcher isn’t allowed to hang onto the ball and make the batter try to steal it — it needs to be thrown over the plate so the batter has a fair chance.

Sociologists today talk about statuses and roles. Your status in society is similar to your position in a baseball game: It defines your relationship to other people and comes with certain freedoms and responsibilities. A role is the set of recommended and required behaviors that go with a status.

Why bother distinguishing between statuses and roles? Because they can both change from one situation to another. There are a different set of statuses in a company (president, vice president, manager, clerk) than there are in a family (mother, father, child, grandparent); and between social groups with similar statuses, those statuses may be associated with different roles. In one family, the father may have the role of disciplinarian, whereas in another he may have the role of nurturer. Your role in a social group gives you a certain set of goals and defines what you can, should, shouldn’t, and can’t do to achieve them.

But if there are different statuses in different social situations, what happens when they come into conflict — when you have to play multiple different positions at the same time? It’s a frustrating situation, but you can try to avoid it by framing the situation to your benefit.

116 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

Frank Abagnale: A true player

The Steven Spielberg movie Catch Me If You Can stars Leonardo DiCaprio as Frank Abagnale, a crook and a fraud who repeatedly eludes capture by the authorities. It’s a true story: Abagnale succeeded in convincing people that he was in turn an airline pilot, a doctor, and an attorney, also managing to cash tens of thousands of dollars in forged checks. (He even claims to have once posed as a sociology professor. The nerve!)

The movie shows how easily Abagnale was able to convince people that he owned statuses he actually had little or no qualification for, just by acting as though he did. He walked right onto planes wearing a stolen pilot’s uniform, won the trust of doctors and nurses just by presenting himself as an authoritative physician, and easily

cashed invalid checks because he so convincingly acted like a wealthy individual who would never need to forge a check.

Abagnale’s story is an extreme example of a person using social cues such as dress and vocabulary to take advantage of others, but everyone tries, every day, to use social cues to their advantage. You may dress a certain way for work, to portray yourself as competent and respectable; or you may act falsely aloof when you’re trying to impress a potential date, creating the impression that you’re a highly soughtafter partner who has no shortage of other romantic possibilities and will really need to be impressed if you’re going to ask someone out. You may even surprise yourself at how often those tricks work!

Stop frontin’: Switching roles, changing frames

As I mention in Chapter 5, the structure of a society defines the set of statuses that are available — and within a society, any given person may have a number of different statuses.

Most of the time, the roles associated with our various statuses are perfectly compatible. For example, my status as a Minnesotan does not conflict with my status as a teacher or my status as a brother. But once in a while, a person’s statuses will come into conflict. What would happen if my sister enrolled in my sociology class? I’d be facing a potential conflict because my

role as a brother requires me to pay special attention to my sister — but my role as a teacher requires me to pay the same amount of attention to each student. Anticipating this kind of possibility, many companies have rules preventing people from supervising anyone they have a family tie or close personal relationship with.

You can’t make rules to prevent every role conflict, though — especially because social life is not like a baseball game where everyone wears a jersey with a number and team name. Roles are often ambiguous, and it’s up to each

Chapter 6: Microsociology: If Life Is a Game, What Are the Rules? 117

person to remember and manage their roles appropriately. Unless they’re very familiar with your identity and status(es), people around you are relying on you to communicate to them what your role is so they can respond appropriately. You can use this ambiguity to your advantage — in fact, to some extent everyone does.

The sociologist best known for writing about this is the late Erving Goffman, author of the 1956 book The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Like Mead, Goffman was interested in the ways that individuals manage their behavior in social situations — but instead of a game, Goffman preferred to use the analogy of a theatrical performance.

When a person behaves a certain way in a certain social setting, Goffman said, it’s like wearing a mask: You’re acting a certain way to convince the people around you that you occupy a certain social position and ought to be treated accordingly. The stage is the social setting you’re in, which determines what “characters” are available to you.

Later, Goffman used the term frame to describe social situations — as in a frame that you put around a picture. Just as a picture frame influences

people’s interpretation of the picture that goes in it, so a social frame influences people’s interpretation of a given interaction. Sometimes situations are naturally framed by the timing or location of an interaction, but in many cases frames are negotiated among people, with each person trying to apply the frame that most benefits him or her.

Here are some examples of how you can use social frames to your benefit:

If you want to ask a stranger for money, you can start by making conversation about some neutral thing like the weather. After you’ve struck up a little chat, the situation is framed as an interaction between acquaintances rather than between strangers. The other person’s role in your interaction is now that of an acquaintance, and the conventional rules of social interaction dictate that acquaintances should try to help each other when they can — whereas strangers have no obligation to do so.

If you want to know whether a coworker might be interested in you romantically, you might ask one of their friends to accompany you on a coffee break. While you’re walking to the coffee shop, you might share some personal piece of information like what you did the past weekend. This helps remove the interaction from the frame of the office — where only official business information is normally exchanged — and puts it in the frame of a social outing, where personal information is more readily exchanged. That makes it more likely that information about romantic attractions will be divulged.

118 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

If you’re operating a museum with free admission but want to encourage visitors to donate, you might require them to wait in line to get a ticket at a counter rather than simply letting them walk into the galleries. Even though they’re not forced to donate, when they are at a counter taking a ticket, it’s a situation so similar to situations where they’d be required to pay that it’s likely they’ll choose to donate much more often than if the situation was framed differently.

So people can choose to turn social situations to their benefit — but do they? As I explain in the previous section, often they do, but often they do not. That’s the paradox of society: you control it . . . but it also controls you. The great insight of the symbolic interactionists is that society fundamentally exists inside people’s heads; it’s something they negotiate among themselves every day.

Chapter 7

Caught in the Web:

The Power of Networks

In This Chapter

Seeing society as a network

Examining the strength of weak ties

Gaining insights from network sociology

One of the most important new ideas affecting sociology in the past few decades is the idea that society can be seen as a network, with each

person being connected to a certain number of other people by professional or personal ties. Seeing society as a network has helped sociologists to understand everything from culture to power to markets.

In this chapter, I explain the basic insights of network sociology and describe some of the most important thinkers and studies in this tradition. I explain specifically how network sociology has changed the way sociologists think about the social world, and why network analysis is one of the most common tools used by sociologists today. Finally, I explain some of the specific ways network sociology might change the way you see your world — and how Web sites like Facebook and MySpace have made us all network sociologists.

The Global Village: Seeing

Society as a Network

Seeing society as a network is not too difficult intuitively, but it has taken sociologists many years — in fact, almost a century — to appreciate the way that network analysis can lend new insights into problems that have concerned sociologists since the time of Comte and before. In this section, I explain how sociologists have learned to use the tools of network analysis.

120 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

It’s all about you: Egocentric networks

In Chapter 6, I discuss some of the ways sociologists have studied individuals in their social world, While many sociologists continued — and continue — to focus on big-picture social facts, as Durkheim did, microsociologists have looked closely at individuals and how they negotiate a world of social symbols and norms, with its maze of rules to learn, remember, and use.

But that left a gap in sociologists’ understanding of society: a gap between the level of societies overall — with their differing cultures and structures — and the level of the individual living in those cultures and structures. Network analysis, which grew out of the microsociological tradition, helps to connect the dots between the individual and society. What connects you to your society? The people you know.

Think about your personal network. It may include:

Your family: your parents, your siblings, your spouse or partner, your children.

Your friends, old and new.

Your coworkers and all the people you are professionally connected with.

The web of acquaintances you encounter in your day-to-day life: the mail carrier, your dentist, the barista at your favorite coffee shop, the guy at the bus stop.

People you may not know personally but who you know of through your own network. People who know the people you know — especially people who are close to people you are also close to and who you might hear about through them — might be considered a part of your network as well.

These are the people you have some connection to, however slight it may be. These are the people who in effect define “society” for you. All of your meaningful social interactions are with these people — with your interactions being especially concentrated among the relatively few people who are closest to you.

Through mass media and other means, you may be able to collect information from — and spread it to — people beyond your social network, but it’s the people in your personal network who constitute your most important conduits of information . . . and influence!

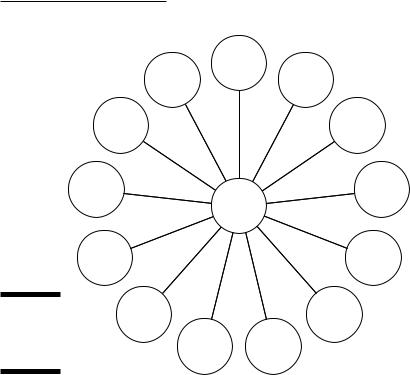

Your personal network is what sociologists refer to as an egocentric network. That doesn’t necessarily mean you have a big head; it’s a technical term referring to a social network as perceived from the standpoint of one individual. The first studies in network sociology were studies of egocentric networks because they’re relatively easy to study. If you’d actually listed the people I referred to in the previous list, I’d have a map of your egocentric network. (See Figure 7-1.)

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 121

|

grandma |

|

|

mom |

|

|

carrier |

|

|

|

|

neighbor |

|

dad |

coworker |

brother #1 |

|

You |

coworker |

brother #2 |

Figure 7-1: |

spouse |

sister |

|

An ego- |

|

|

|

centric |

friend |

friend |

|

network. |

|||

|

|

But what about the people your contacts are connected to — the people you don’t know personally, but who you know through other contacts?

The game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” in which players are challenged to connect Kevin Bacon to any given actor in Hollywood via chains of costars, is inspired by a longstanding conjecture that every person in the world is fewer than six degrees away from any other person, with each “degree” being a connection by personal acquaintance. Whomever I might name in the world, goes the theory, you at least know someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows someone who knows her. It’s a tough theory to test, but a number of different studies have found that it’s at least roughly accurate.

In other words, you’re connected through chains of acquaintance to almost every person on Earth. But does it matter?

Yes and no. Certainly, in some cases multi-degree social connections can be valuable and meaningful (see the several examples elsewhere in this chapter) — but even a first-degree social connection is of limited use if it’s not very close. When I was applying to graduate school at Harvard, I asked an acquaintance who is a Harvard alumnus whether he would be willing to write me a letter of recommendation. “Um . . . sure,” he replied. “What we’re going to have to finesse, though, is the fact that I’ve only met you once.”

122 Part II: Seeing Society Like a Sociologist

Social networks and social manners: A rude awakening

David Gibson is a sociologist who is combining the insights of network analysis with the kind of microsociological observation that Erving Goffman and members of the Chicago School would appreciate.

In a study of a large banking corporation, Gibson first surveyed the bank’s employees to map the various social connections among them. He then sat in a series of meetings, quietly observing how the different employees in the meeting interacted with one another. You might expect that the people who knew each other best would feel most free talking with one another and would exchange the most information, but Gibson found that in fact that was not the case: A lot of conversation went on among people who were not closely connected. After all, the point of a meeting is to create a social situation where information is shared, and the people who worked most closely together had

already shared a lot of information outside the meeting.

A good way of predicting which employees knew one another best, Gibson found, was to see which employees took one another’s turns in conversation. People who knew one another well might even seem to be rude to each other, answering questions asked of the other person and interrupting him or her when she was talking.

You can observe this effect at parties. Watch people who are close friends or romantic partners; they’ll often stand beside one another in conversational circles and field questions together, interrupting each other in a (hopefully) friendly fashion to clarify details or add anecdotes. They’ve become so close that they’re essentially functioning as a single conversational unit. If one of them interrupted someone else, though . . . now that would be rude!

Sociologists often study networks of individual people, but network analysis can also be applied to networks of groups or organizations. For certain studies it may be useful to think of your family as being part of a network of families who live in the same neighborhood or attend the same church, or to think of your company as being part of a network of companies that do business with one another. The tools and strategies used to study networks of individuals can also be applied to networks of groups.

A web of relationships

Your network is large — it probably contains hundreds of people you could list offhand if you thought about it carefully and systematically, plus hundreds more you wouldn’t even think to list (which is a problem for studies of egocentric networks), but it doesn’t include all the people in the world. In

fact, it probably doesn’t even include everyone in your company or school, in your neighborhood or apartment building, or all the people you’re related to beyond first or second cousins.

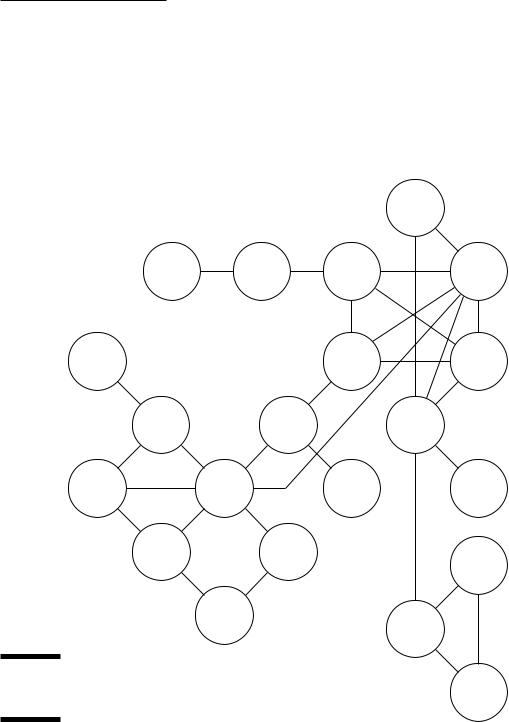

Chapter 7: Caught in the Web: The Power of Networks 123

Imagine drawing a network map of your school or the company where you work. There would be a dot for each individual, and each individual would be connected to each individual they know personally. You can imagine that there would be clusters of tight-knit groups — cliques of friends or coworkers who all know one another well — and that each person in a cluster would share some number of connections to people outside the cluster. If you could actually draw every personal connection in your school or company, you would have a complete network map of that organization. (See Figure 7-2.)

Jay

Bob |

Jaclyn |

Joel |

Dan |

Cyn |

Rich |

Rachel |

Jean |

Mary |

Emily |

Dwight |

Jeremy |

Madeleine |

Ariah |

Crystal |

Jon |

Jim

Jennifer

Jason

Figure 7-2:

A complete Jeanette network.