Mankiw Principles of Economics (3rd ed)

.pdf

410 |

PART SIX THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS |

Table 18-3

PRODUCTIVITY AND WAGE

GROWTH AROUND THE WORLD

|

GROWTH RATE |

GROWTH RATE |

COUNTRY |

OF PRODUCTIVITY |

OF REAL WAGES |

|

|

|

South Korea |

8.5 |

7.9 |

Hong Kong |

5.5 |

4.9 |

Singapore |

5.3 |

5.0 |

Indonesia |

4.0 |

4.4 |

Japan |

3.6 |

2.0 |

India |

3.1 |

3.4 |

United Kingdom |

2.4 |

2.4 |

United States |

1.7 |

0.5 |

Brazil |

0.4 |

2.4 |

Mexico |

0.2 |

3.0 |

Argentina |

0.9 |

1.3 |

Iran |

1.4 |

7.9 |

|

|

|

SOURCE: World Development Report 1994, table 1, pp. 162–163, and table 7, pp. 174–175. Growth in productivity is measured here as the annualized rate of change in gross national product per person from 1980 to 1992. Growth in wages is measured as the annualized change in earnings per employee in manufacturing from 1980 to 1991.

QUICK QUIZ: How does an immigration of workers affect labor supply, labor demand, the marginal product of labor, and the equilibrium wage?

capital

the equipment and structures used to produce goods and services

THE OTHER FACTORS OF PRODUCTION:

LAND AND CAPITAL

We have seen how firms decide how much labor to hire and how these decisions determine workers’ wages. At the same time that firms are hiring workers, they are also deciding about other inputs to production. For example, our appleproducing firm might have to choose the size of its apple orchard and the number of ladders to make available to its apple pickers. We can think of the firm’s factors of production as falling into three categories: labor, land, and capital.

The meaning of the terms labor and land is clear, but the definition of capital is somewhat tricky. Economists use the term capital to refer to the stock of equipment and structures used for production. That is, the economy’s capital represents the accumulation of goods produced in the past that are being used in the present to produce new goods and services. For our apple firm, the capital stock includes the ladders used to climb the trees, the trucks used to transport the apples, the buildings used to store the apples, and even the trees themselves.

EQUILIBRIUM IN THE MARKETS FOR LAND AND CAPITAL

What determines how much the owners of land and capital earn for their contribution to the production process? Before answering this question, we need to

CHAPTER 18 |

THE MARKETS FOR THE FACTORS OF PRODUCTION |

411 |

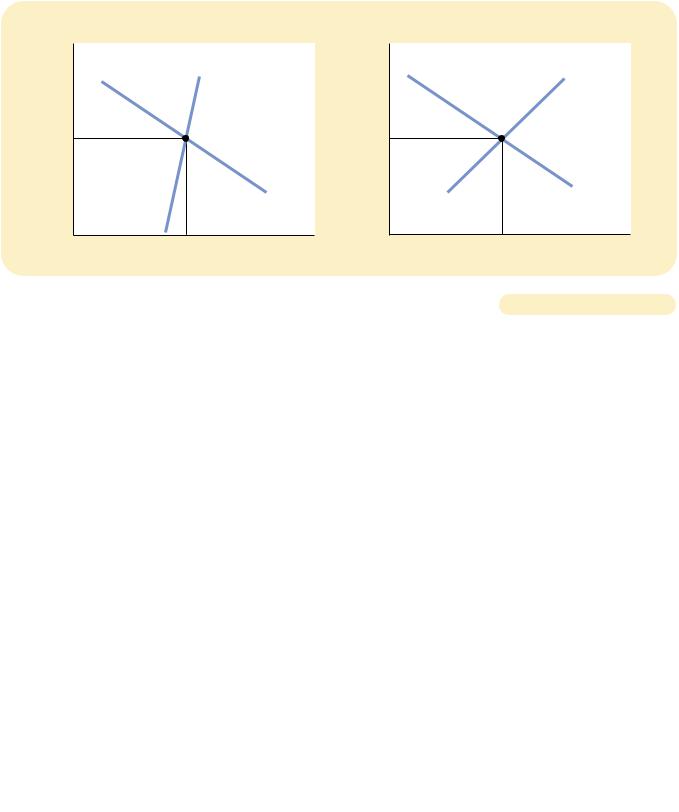

(a) The Market for Land |

(b) The Market for Capital |

|

Rental |

|

|

Rental |

Price of |

Supply |

|

Price of |

Land |

|

Capital |

|

|

|

||

P |

|

|

P |

|

|

Demand |

|

0 |

Q |

Quantity of |

0 |

|

|

Land |

|

|

Supply |

|

Demand |

Q |

Quantity of |

|

Capital |

THE MARKETS FOR LAND AND CAPITAL. Supply and demand determine the |

Figure 18-7 |

||

compensation paid to the owners of land, as shown in panel (a), and the compensation |

|||

|

|||

paid to the owners of capital, as shown in panel (b). The demand for each factor, in turn, |

|

||

depends on the value of the marginal product of that factor. |

|

||

|

|

|

|

distinguish between two prices: the purchase price and the rental price. The purchase price of land or capital is the price a person pays to own that factor of production indefinitely. The rental price is the price a person pays to use that factor for a limited period of time. It is important to keep this distinction in mind because, as we will see, these prices are determined by somewhat different economic forces.

Having defined these terms, we can now apply the theory of factor demand we developed for the labor market to the markets for land and capital. The wage is, after all, simply the rental price of labor. Therefore, much of what we have learned about wage determination applies also to the rental prices of land and capital. As Figure 18-7 illustrates, the rental price of land, shown in panel (a), and the rental price of capital, shown in panel (b), are determined by supply and demand. Moreover, the demand for land and capital is determined just like the demand for labor. That is, when our apple-producing firm is deciding how much land and how many ladders to rent, it follows the same logic as when deciding how many workers to hire. For both land and capital, the firm increases the quantity hired until the value of the factor’s marginal product equals the factor’s price. Thus, the demand curve for each factor reflects the marginal productivity of that factor.

We can now explain how much income goes to labor, how much goes to landowners, and how much goes to the owners of capital. As long as the firms using the factors of production are competitive and profit-maximizing, each factor’s rental price must equal the value of the marginal product for that factor.

Labor, land, and capital each earn the value of their marginal contribution to the production process.

Now consider the purchase price of land and capital. The rental price and the purchase price are obviously related: Buyers are willing to pay more to buy a piece of land or capital if it produces a valuable stream of rental income. And, as we

THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS

Labor income is an easy concept to understand: It is the paycheck that workers get from their employers. The income earned by capital, however, is less obvious.

In our analysis, we have been implicitly assuming that households own the economy’s stock of capital—ladders, drill presses, warehouses, etc.— and rent it to the firms that use it. Capital income, in this case,

is the rent that households receive for the use of their capital. This assumption simplified our analysis of how capital owners are compensated, but it is not entirely realistic. In fact, firms usually own the capital they use and, therefore, they receive the earnings from this capital.

These earnings from capital, however, eventually get paid to households. Some of the earnings are paid in the form of interest to those households who have lent money to firms. Bondholders and bank depositors are two examples of recipients of interest. Thus, when you receive inter-

est on your bank account, that income is part of the economy’s capital income.

In addition, some of the earnings from capital are paid to households in the form of dividends. Dividends are payments by a firm to the firm’s stockholders. A stockholder is a person who has bought a share in the ownership of the firm and, therefore, is entitled to share in the firm’s profits.

A firm does not have to pay out all of its earnings to households in the form of interest and dividends. Instead, it can retain some earnings within the firm and use these earnings to buy additional capital. Although these retained earnings do not get paid to the firm’s stockholders, the stockholders benefit from them nonetheless. Because retained earnings increase the amount of capital the firm owns, they tend to increase future earnings and, thereby, the value of the firm’s stock.

These institutional details are interesting and important, but they do not alter our conclusion about the income earned by the owners of capital. Capital is paid according to the value of its marginal product, regardless of whether this income gets transmitted to households in the form of interest or dividends or whether it is kept within firms as retained earnings.

have just seen, the equilibrium rental income at any point in time equals the value of that factor’s marginal product. Therefore, the equilibrium purchase price of a piece of land or capital depends on both the current value of the marginal product and the value of the marginal product expected to prevail in the future.

LINKAGES AMONG THE FACTORS OF PRODUCTION

We have seen that the price paid to any factor of production—labor, land, or capi- tal—equals the value of the marginal product of that factor. The marginal product of any factor, in turn, depends on the quantity of that factor that is available. Because of diminishing returns, a factor in abundant supply has a low marginal product and thus a low price, and a factor in scarce supply has a high marginal product and a high price. As a result, when the supply of a factor falls, its equilibrium factor price rises.

When the supply of any factor changes, however, the effects are not limited to the market for that factor. In most situations, factors of production are used together in a way that makes the productivity of each factor dependent on the quantities of the other factors available to be used in the production process. As a result, a change in the supply of any one factor alters the earnings of all the factors.

For example, suppose that a hurricane destroys many of the ladders that workers use to pick apples from the orchards. What happens to the earnings of the various factors of production? Most obviously, the supply of ladders falls and,

CHAPTER 18 THE MARKETS FOR THE FACTORS OF PRODUCTION |

413 |

therefore, the equilibrium rental price of ladders rises. Those owners who were lucky enough to avoid damage to their ladders now earn a higher return when they rent out their ladders to the firms that produce apples.

Yet the effects of this event do not stop at the ladder market. Because there are fewer ladders with which to work, the workers who pick apples have a smaller marginal product. Thus, the reduction in the supply of ladders reduces the demand for the labor of apple pickers, and this causes the equilibrium wage to fall.

This story shows a general lesson: An event that changes the supply of any factor of production can alter the earnings of all the factors. The change in earnings of any factor can be found by analyzing the impact of the event on the value of the marginal product of that factor.

CASE STUDY THE ECONOMICS OF THE BLACK DEATH

In fourteenth-century Europe, the bubonic plague wiped out about one-third of the population within a few years. This event, called the Black Death, provides a grisly natural experiment to test the theory of factor markets that we have just developed. Consider the effects of the Black Death on those who were lucky enough to survive. What do you think happened to the wages earned by workers and the rents earned by landowners?

To answer this question, let’s examine the effects of a reduced population on the marginal product of labor and the marginal product of land. With a smaller supply of workers, the marginal product of labor rises. (This is simply diminishing marginal product working in reverse.) Thus, we would expect the Black Death to raise wages.

Because land and labor are used together in production, a smaller supply of workers also affects the market for land, the other major factor of production in medieval Europe. With fewer workers available to farm the land, an additional unit of land produced less additional output. In other words, the marginal product of land fell. Thus, we would expect the Black Death to lower rents.

In fact, both predictions are consistent with the historical evidence. Wages approximately doubled during this period, and rents declined 50 percent or more. The Black Death led to economic prosperity for the peasant classes and reduced incomes for the landed classes.

QUICK QUIZ: What determines the income of the owners of land and capital? How would an increase in the quantity of capital affect the incomes of those who already own capital? How would it affect the incomes of workers?

WORKERS WHO SURVIVED THE PLAGUE WERE LUCKY IN MORE WAYS THAN ONE.

CONCLUSION

This chapter explained how labor, land, and capital are compensated for the roles they play in the production process. The theory developed here is called the neoclassical theory of distribution. According to the neoclassical theory, the amount paid to each factor of production depends on the supply and demand for that factor.

414 |

PART SIX THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS |

The demand, in turn, depends on that particular factor’s marginal productivity. In equilibrium, each factor of production earns the value of its marginal contribution to the production of goods and services.

The neoclassical theory of distribution is widely accepted. Most economists begin with the neoclassical theory when trying to explain how the U.S. economy’s $8 trillion of income is distributed among the economy’s various members. In the following two chapters, we consider the distribution of income in more detail. As you will see, the neoclassical theory provides the framework for this discussion.

Even at this point you can use the theory to answer the question that began this chapter: Why are computer programmers paid more than gas station attendants? It is because programmers can produce a good of greater market value than can a gas station attendant. People are willing to pay dearly for a good computer game, but they are willing to pay little to have their gas pumped and their windshield washed. The wages of these workers reflect the market prices of the goods they produce. If people suddenly got tired of using computers and decided to spend more time driving, the prices of these goods would change, and so would the equilibrium wages of these two groups of workers.

Summar y

The economy’s income is distributed the factors of production. The factors of production are labor,

The demand for factors, such as demand that comes from firms produce goods and services. maximizing firms hire each factor which the value of the marginal equals its price.

The supply of labor arises from between work and leisure. An supply curve means that people in the wage by enjoying less hours.

Key Concepts

each factor adjusts to balance the for that factor. Because factor value of the marginal product of

each factor is compensated marginal contribution to the production

.

production are used together, the any one factor depends on the

that are available. As a result, a of one factor alters the equilibrium

factors.

factors of production, p. 398 production function, p. 400

of the marginal product, p. 401 capital, p. 410

Questions for Review

1.Explain how a firm’s production function is related to its marginal product of labor, how a firm’s marginal product of labor is related to the value

of its marginal product, and how a firm’s value of marginal product is related to its demand for labor.

CHAPTER 18 THE MARKETS FOR THE FACTORS OF PRODUCTION |

415 |

2.Give two examples of events that could shift the demand for labor.

3.Give two examples of events that could shift the supply of labor.

4.Explain how the wage can adjust and demand for labor while

the value of the marginal product

5.If the population of the United States suddenly grew because of a large immigration, what would happen to wages? What would happen to the rents earned by the owners of land and capital?

Problems and Applications

1.Suppose that the president proposes a new law aimed at reducing heath care costs: All Americans are to be required to eat one apple daily.

a.How would this apple-a-day law affect the demand and equilibrium price of apples?

b.How would the law affect the marginal product and the value of the marginal product of apple pickers?

c.How would the law affect the demand and equilibrium wage for apple pickers?

2.Henry Ford once said: “It is not the employer who pays wages—he only handles the money. It is the product that pays wages.” Explain.

3.Show the effect of each of the following events on the market for labor in the computer manufacturing industry.

a.Congress buys personal computers for all American college students.

b.More college students major in engineering and computer science.

c.Computer firms build new manufacturing plants.

4.Your enterprising uncle opens a sandwich shop that employs 7 people. The employees are paid $6 per hour, and a sandwich sells for $3. If your uncle is maximizing his profit, what is the value of the marginal product of the last worker he hired? What is that worker’s marginal product?

5.Imagine a firm that hires two types of workers—some with computer skills and some without. If technology advances, so that computers become more useful to the firm, what happens to the marginal product of the two types? What happens to equilibrium wages? Explain, using appropriate diagrams.

6.Suppose a freeze in Florida destroys part of the Florida orange crop.

a.Explain what happens to the price of oranges and the marginal product of orange pickers as a result

of the freeze. Can you say what happens to the demand for orange pickers? Why or why not?

b.Suppose the price of oranges doubles and the marginal product falls by 30 percent. What happens to the equilibrium wage of orange pickers?

c.Suppose the price of oranges rises by 30 percent and the marginal product falls by 50 percent. What happens to the equilibrium wage of orange pickers?

7.During the 1980s and 1990s the United States experienced a significant inflow of capital from other countries. For example, Toyota, BMW, and other foreign car companies built auto plants in the United States.

a.Using a diagram of the U.S. capital market, show the effect of this inflow on the rental price of capital in the United States and on the quantity of capital in use.

b.Using a diagram of the U.S. labor market, show the effect of the capital inflow on the average wage paid to U.S. workers.

8.Suppose that labor is the only input used by a perfectly competitive firm that can hire workers for $50 per day. The firm’s production function is as follows:

DAYS OF LABOR |

UNITS OF OUTPUT |

|

|

0 |

0 |

1 |

7 |

2 |

13 |

3 |

19 |

4 |

25 |

5 |

28 |

6 |

29 |

Each unit of output sells for $10. Plot the firm’s demand for labor. How many days of labor should the firm hire? Show this point on your graph.

416 |

PART SIX THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS |

9.(This question is challenging.) In recent years some policymakers have proposed requiring firms to give workers certain fringe benefits. For example, in 1993 President Clinton proposed requiring firms to provide health insurance to their workers. Let’s consider the effects of such a policy on the labor market.

a.Suppose that a law required firms to give each worker $3 of fringe benefits for every hour that the worker is employed by the firm. How does this law affect the marginal profit that a firm earns from each worker? How does the law affect the demand curve for labor? Draw your answer on a graph with the cash wage on the vertical axis.

b.If there is no change in labor supply, how would this law affect employment and wages?

c.Why might the labor supply curve shift in response to this law? Would this shift in labor supply raise or lower the impact of the law on wages and employment?

d.As Chapter 6 discussed, the wages of some workers, particularly the unskilled and

inexperienced, are kept above the equilibrium level by minimum-wage laws. What effect would a fringe-benefit mandate have for these workers?

10.(This question is challenging.) This chapter has assumed that labor is supplied by individual workers acting competitively. In some markets, however, the supply of labor is determined by a union of workers.

a.Explain why the situation faced by a labor union may resemble the situation faced by a monopoly firm.

b.The goal of a monopoly firm is to maximize profits. Is there an analogous goal for labor unions?

c.Now extend the analogy between monopoly firms and unions. How do you suppose that the wage set by a union compares to the wage in a competitive market? How do you suppose employment differs in the two cases?

d.What other goals might unions have that make unions different from monopoly firms?

E A R N I N G S A N D

D I S C R I M I N A T I O N

In the United States today, the typical physician earns about $200,000 a year, the typical police officer about $50,000, and the typical farmworker about $20,000. These examples illustrate the large differences in earnings that are so common in our economy. These differences explain why some people live in mansions, ride in limousines, and vacation on the French Riviera, while other people live in small apartments, ride the bus, and vacation in their own back yards.

Why do earnings vary so much from person to person? Chapter 18, which developed the basic neoclassical theory of the labor market, offers an answer to this question. There we saw that wages are governed by labor supply and labor demand. Labor demand, in turn, reflects the marginal productivity of labor. In equilibrium, each worker is paid the value of his or her marginal contribution to the economy’s production of goods and services.

IN THIS CHAPTER YOU WILL . . .

Examine how wages compensate for

dif fer ences in job characteristics

Learn and compar e the human - capital and signaling theories of education

Examine why in some occupations a few superstars ear n tr emendous incomes

Lear n why wages rise above the level that balances supply and demand

Consider why it is dif ficult to measur e the impact of discrimination on wages

See when market for ces can and cannot pr ovide a natural r emedy for discrimination

Consider the debate over comparable wor th as a system for setting wages

417

418 |

PART SIX THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS |

This theory of the labor market, though widely accepted by economists, is only the beginning of the story. To understand the wide variation in earnings that we observe, we must go beyond this general framework and examine more precisely what determines the supply and demand for different types of labor. That is our goal in this chapter.

SOME DETERMINANTS OF EQUILIBRIUM WAGES

Workers differ from one another in many ways. Jobs also have differing character- istics—both in terms of the wage they pay and in terms of their nonmonetary attributes. In this section we consider how the characteristics of workers and jobs affect labor supply, labor demand, and equilibrium wages.

COMPENSATING DIFFERENTIALS

When a worker is deciding whether to take a job, the wage is only one of many job attributes that the worker takes into account. Some jobs are easy, fun, and safe; others are hard, dull, and dangerous. The better the job as gauged by these nonmonetary characteristics, the more people there are who are willing to do the job at any

“On the one hand, I know I could make more money if I left public service for the private sector, but, on the other hand, I couldn’t chop off heads.”

CHAPTER 19 EARNINGS AND DISCRIMINATION |

419 |

given wage. In other words, the supply of labor for easy, fun, and safe jobs is greater than the supply of labor for hard, dull, and dangerous jobs. As a result, “good” jobs will tend to have lower equilibrium wages than “bad” jobs.

For example, imagine you are looking for a summer job in the local beach community. Two kinds of jobs are available. You can take a job as a beach-badge checker, or you can take a job as a garbage collector. The beach-badge checkers take leisurely strolls along the beach during the day and check to make sure the tourists have bought the required beach permits. The garbage collectors wake up before dawn to drive dirty, noisy trucks around town to pick up garbage. Which job would you want? Most people would prefer the beach job if the wages were the same. To induce people to become garbage collectors, the town has to offer higher wages to garbage collectors than to beach-badge checkers.

Economists use the term compensating differential to refer to a difference in wages that arises from nonmonetary characteristics of different jobs. Compensating differentials are prevalent in the economy. Here are some examples:

Coal miners are paid more than other workers with similar levels of education. Their higher wage compensates them for the dirty and dangerous nature of coal mining, as well as the long-term health problems that coal miners experience.

Workers who work the night shift at factories are paid more than similar workers who work the day shift. The higher wage compensates them for having to work at night and sleep during the day, a lifestyle that most people find undesirable.

Professors are paid less than lawyers and doctors, who have similar amounts of education. Professors’ lower wages compensate them for the great intellectual and personal satisfaction that their jobs offer. (Indeed, teaching economics is so much fun that it is surprising that economics professors get paid anything at all!)

HUMAN CAPITAL

As we discussed in the previous chapter, the word capital usually refers to the economy’s stock of equipment and structures. The capital stock includes the farmer’s tractor, the manufacturer’s factory, and the teacher’s blackboard. The essence of capital is that it is a factor of production that itself has been produced.

There is another type of capital that, while less tangible than physical capital, is just as important to the economy’s production. Human capital is the accumulation of investments in people. The most important type of human capital is education. Like all forms of capital, education represents an expenditure of resources at one point in time to raise productivity in the future. But, unlike an investment in other forms of capital, an investment in education is tied to a specific person, and this linkage is what makes it human capital.

Not surprisingly, workers with more human capital on average earn more than those with less human capital. College graduates in the United States, for example, earn about twice as much as those workers who end their education with a high school diploma. This large difference has been documented in many countries around the world. It tends to be even larger in less developed countries, where educated workers are in scarce supply.

compensating dif ferential a difference in wages that arises

to offset the nonmonetary characteristics of different jobs

human capital

the accumulation of investments in people, such as education and on-the- job training