Mankiw Principles of Economics (3rd ed)

.pdf

388 |

PART FIVE FIRM BEHAVIOR AND THE ORGANIZATION OF INDUSTRY |

important as the fact that consumers know ads are expensive. By contrast, cheap advertising cannot be effective at signaling quality to consumers. In our example, if an advertising campaign cost less than $3 million, both Post and Kellogg would use it to market their new cereals. Because both good and mediocre cereals would be advertised, consumers could not infer the quality of a new cereal from the fact that it is advertised. Over time, consumers would learn to ignore such cheap advertising.

This theory can explain why firms pay famous actors large amounts of money to make advertisements that, on the surface, appear to convey no information at all. The information is not in the advertisement’s content, but simply in its existence and expense.

BRAND NAMES

Advertising is closely related to the existence of brand names. In many markets, there are two types of firms. Some firms sell products with widely recognized brand names, while other firms sell generic substitutes. For example, in a typical drugstore, you can find Bayer aspirin on the shelf next to a generic aspirin. In a typical grocery store, you can find Pepsi next to less familiar colas. Most often, the firm with the brand name spends more on advertising and charges a higher price for its product.

Just as there is disagreement about the economics of advertising, there is disagreement about the economics of brand names. Let’s consider both sides of the debate.

Critics of brand names argue that brand names cause consumers to perceive differences that do not really exist. In many cases, the generic good is almost indistinguishable from the brand-name good. Consumers’ willingness to pay more for the brand-name good, these critics assert, is a form of irrationality fostered by advertising. Economist Edward Chamberlin, one of the early developers of the theory of monopolistic competition, concluded from this argument that brand names were bad for the economy. He proposed that the government discourage

CHAPTER 17 MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION |

389 |

their use by refusing to enforce the exclusive trademarks that companies use to identify their products.

More recently, economists have defended brand names as a useful way for consumers to ensure that the goods they buy are of high quality. There are two related arguments. First, brand names provide consumers information about quality when quality cannot be easily judged in advance of purchase. Second, brand names give firms an incentive to maintain high quality, because firms have a financial stake in maintaining the reputation of their brand names.

To see how these arguments work in practice, consider a famous brand name: McDonald’s hamburgers. Imagine that you are driving through an unfamiliar town and want to stop for lunch. You see a McDonald’s and a local restaurant next to it. Which do you choose? The local restaurant may in fact offer better food at lower prices, but you have no way of knowing that. By contrast, McDonald’s offers a consistent product across many cities. Its brand name is useful to you as a way of judging the quality of what you are about to buy.

The McDonald’s brand name also ensures that the company has an incentive to maintain quality. For example, if some customers were to become ill from bad food sold at a McDonald’s, the news would be disastrous for the company. McDonald’s would lose much of the valuable reputation that it has built up with years of expensive advertising. As a result, it would lose sales and profit not just in the outlet that sold the bad food but in its many outlets throughout the country. By contrast, if some customers were to become ill from bad food at a local restaurant, that restaurant might have to close down, but the lost profits would be much smaller. Hence, McDonald’s has a greater incentive to ensure that its food is safe.

The debate over brand names thus centers on the question of whether consumers are rational in preferring brand names over generic substitutes. Critics of brand names argue that brand names are the result of an irrational consumer response to advertising. Defenders of brand names argue that consumers have good reason to pay more for brand-name products because they can be more confident in the quality of these products.

CASE STUDY BRAND NAMES UNDER COMMUNISM

Defenders of brand names get some support for their view from experiences in the former Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union adhered to the principles of communism, central planners in the government replaced the invisible hand of the marketplace. Yet, just like consumers living in an economy with free markets, Soviet central planners learned that brand names were useful in helping to ensure product quality.

In an article published in the Journal of Political Economy in 1960, Marshall Goldman, an expert on the Soviet economy, described the Soviet experience:

In the Soviet Union, production goals have been set almost solely in quantitative or value terms, with the result that, in order to meet the plan, quality is often sacrificed. . . . Among the methods adopted by the Soviets to deal with this problem, one is of particular interest to us—intentional product differentiation. . . . In order to distinguish one firm from similar firms in the same industry or ministry, each firm has its own name. Whenever it is

398 |

PART SIX THE ECONOMICS OF LABOR MARKETS |

|

|

|

landowners higher rental income than others, and some capital owners greater |

|

|

profit than others? Why, in particular, do computer programmers earn more than |

|

|

gas station attendants? |

|

|

The answers to these questions, like most in economics, hinge on supply and |

|

|

demand. The supply and demand for labor, land, and capital determine the prices |

|

|

paid to workers, landowners, and capital owners. To understand why some peo- |

|

|

ple have higher incomes than others, therefore, we need to look more deeply at |

|

|

the markets for the services they provide. That is our job in this and the next two |

|

|

chapters. |

|

|

This chapter provides the basic theory for the analysis of factor markets. As |

factors of production |

you may recall from Chapter 2, the factors of production are the inputs used to |

|

the inputs used to produce goods and produce goods and services. Labor, land, and capital are the three most important

services |

factors of production. When a computer firm produces a new software program, it |

|

uses programmers’ time (labor), the physical space on which its offices sit (land), |

|

and an office building and computer equipment (capital). Similarly, when a gas |

|

station sells gas, it uses attendants’ time (labor), the physical space (land), and the |

|

gas tanks and pumps (capital). |

|

Although in many ways factor markets resemble the goods markets we have |

|

analyzed in previous chapters, they are different in one important way: The de- |

|

mand for a factor of production is a derived demand. That is, a firm’s demand for a |

|

factor of production is derived from its decision to supply a good in another mar- |

|

ket. The demand for computer programmers is inextricably tied to the supply of |

|

computer software, and the demand for gas station attendants is inextricably tied |

|

to the supply of gasoline. |

|

In this chapter we analyze factor demand by considering how a competitive, |

|

profit-maximizing firm decides how much of any factor to buy. We begin our |

|

analysis by examining the demand for labor. Labor is the most important factor of |

|

production, for workers receive most of the total income earned in the U.S. econ- |

|

omy. Later in the chapter, we see that the lessons we learn about the labor market |

|

apply directly to the markets for the other factors of production. |

|

The basic theory of factor markets developed in this chapter takes a large step |

|

toward explaining how the income of the U.S. economy is distributed among |

|

workers, landowners, and owners of capital. Chapter 19 will build on this analysis |

|

to examine in more detail why some workers earn more than others. Chapter 20 |

|

will examine how much inequality results from this process and then consider |

|

what role the government should and does play in altering the distribution of |

|

income. |

THE DEMAND FOR LABOR

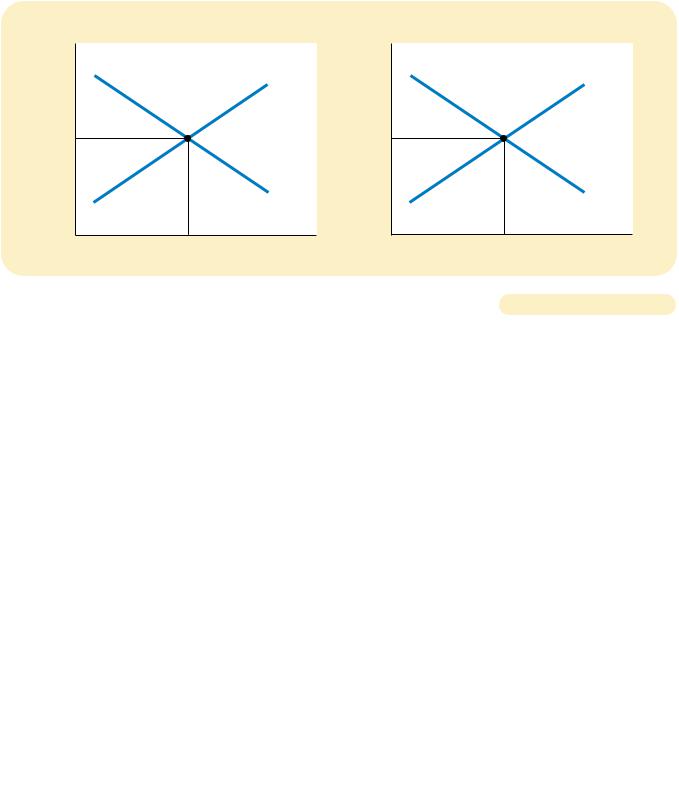

Labor markets, like other markets in the economy, are governed by the forces of supply and demand. This is illustrated in Figure 18-1. In panel (a) the supply and demand for apples determine the price of apples. In panel (b) the supply and demand for apple pickers determine the price, or wage, of apple pickers.

As we have already noted, labor markets are different from most other markets because labor demand is a derived demand. Most labor services, rather than