- •Using Your Sybex Electronic Book

- •Acknowledgments

- •Contents at a Glance

- •Introduction

- •Who Should Read This Book?

- •How About the Advanced Topics?

- •The Structure of the Book

- •How to Reach the Author

- •The Integrated Development Environment

- •The Start Page

- •Project Types

- •Your First VB Application

- •Making the Application More Robust

- •Making the Application More User-Friendly

- •The IDE Components

- •The IDE Menu

- •The Toolbox Window

- •The Solution Explorer

- •The Properties Window

- •The Output Window

- •The Command Window

- •The Task List Window

- •Environment Options

- •A Few Common Properties

- •A Few Common Events

- •A Few Common Methods

- •Building a Console Application

- •Summary

- •Building a Loan Calculator

- •How the Loan Application Works

- •Designing the User Interface

- •Programming the Loan Application

- •Validating the Data

- •Building a Math Calculator

- •Designing the User Interface

- •Programming the MathCalculator App

- •Adding More Features

- •Exception Handling

- •Taking the LoanCalculator to the Web

- •Working with Multiple Forms

- •Working with Multiple Projects

- •Executable Files

- •Distributing an Application

- •VB.NET at Work: Creating a Windows Installer

- •Finishing the Windows Installer

- •Running the Windows Installer

- •Verifying the Installation

- •Summary

- •Variables

- •Declaring Variables

- •Types of Variables

- •Converting Variable Types

- •User-Defined Data Types

- •Examining Variable Types

- •Why Declare Variables?

- •A Variable’s Scope

- •The Lifetime of a Variable

- •Constants

- •Arrays

- •Declaring Arrays

- •Initializing Arrays

- •Array Limits

- •Multidimensional Arrays

- •Dynamic Arrays

- •Arrays of Arrays

- •Variables as Objects

- •So, What’s an Object?

- •Formatting Numbers

- •Formatting Dates

- •Flow-Control Statements

- •Test Structures

- •Loop Structures

- •Nested Control Structures

- •The Exit Statement

- •Summary

- •Modular Coding

- •Subroutines

- •Functions

- •Arguments

- •Argument-Passing Mechanisms

- •Event-Handler Arguments

- •Passing an Unknown Number of Arguments

- •Named Arguments

- •More Types of Function Return Values

- •Overloading Functions

- •Summary

- •The Appearance of Forms

- •Properties of the Form Control

- •Placing Controls on Forms

- •Setting the TabOrder

- •VB.NET at Work: The Contacts Project

- •Anchoring and Docking

- •Loading and Showing Forms

- •The Startup Form

- •Controlling One Form from within Another

- •Forms vs. Dialog Boxes

- •VB.NET at Work: The MultipleForms Project

- •Designing Menus

- •The Menu Editor

- •Manipulating Menus at Runtime

- •Building Dynamic Forms at Runtime

- •The Form.Controls Collection

- •VB.NET at Work: The DynamicForm Project

- •Creating Event Handlers at Runtime

- •Summary

- •The TextBox Control

- •Basic Properties

- •Text-Manipulation Properties

- •Text-Selection Properties

- •Text-Selection Methods

- •Undoing Edits

- •VB.NET at Work: The TextPad Project

- •Capturing Keystrokes

- •The ListBox, CheckedListBox, and ComboBox Controls

- •Basic Properties

- •The Items Collection

- •VB.NET at Work: The ListDemo Project

- •Searching

- •The ComboBox Control

- •The ScrollBar and TrackBar Controls

- •The ScrollBar Control

- •The TrackBar Control

- •Summary

- •The Common Dialog Controls

- •Using the Common Dialog Controls

- •The Color Dialog Box

- •The Font Dialog Box

- •The Open and Save As Dialog Boxes

- •The Print Dialog Box

- •The RichTextBox Control

- •The RTF Language

- •Methods

- •Advanced Editing Features

- •Cutting and Pasting

- •Searching in a RichTextBox Control

- •Formatting URLs

- •VB.NET at Work: The RTFPad Project

- •Summary

- •What Is a Class?

- •Building the Minimal Class

- •Adding Code to the Minimal Class

- •Property Procedures

- •Customizing Default Members

- •Custom Enumerations

- •Using the SimpleClass in Other Projects

- •Firing Events

- •Shared Properties

- •Parsing a Filename String

- •Reusing the StringTools Class

- •Encapsulation and Abstraction

- •Inheritance

- •Inheriting Existing Classes

- •Polymorphism

- •The Shape Class

- •Object Constructors and Destructors

- •Instance and Shared Methods

- •Who Can Inherit What?

- •Parent Class Keywords

- •Derived Class Keyword

- •Parent Class Member Keywords

- •Derived Class Member Keyword

- •MyBase and MyClass

- •Summary

- •On Designing Windows Controls

- •Enhancing Existing Controls

- •Building the FocusedTextBox Control

- •Building Compound Controls

- •VB.NET at Work: The ColorEdit Control

- •VB.NET at Work: The Label3D Control

- •Raising Events

- •Using the Custom Control in Other Projects

- •VB.NET at Work: The Alarm Control

- •Designing Irregularly Shaped Controls

- •Designing Owner-Drawn Menus

- •Designing Owner-Drawn ListBox Controls

- •Using ActiveX Controls

- •Summary

- •Programming Word

- •Objects That Represent Text

- •The Documents Collection and the Document Object

- •Spell-Checking Documents

- •Programming Excel

- •The Worksheets Collection and the Worksheet Object

- •The Range Object

- •Using Excel as a Math Parser

- •Programming Outlook

- •Retrieving Information

- •Recursive Scanning of the Contacts Folder

- •Summary

- •Advanced Array Topics

- •Sorting Arrays

- •Searching Arrays

- •Other Array Operations

- •Array Limitations

- •The ArrayList Collection

- •Creating an ArrayList

- •Adding and Removing Items

- •The HashTable Collection

- •VB.NET at Work: The WordFrequencies Project

- •The SortedList Class

- •The IEnumerator and IComparer Interfaces

- •Enumerating Collections

- •Custom Sorting

- •Custom Sorting of a SortedList

- •The Serialization Class

- •Serializing Individual Objects

- •Serializing a Collection

- •Deserializing Objects

- •Summary

- •Handling Strings and Characters

- •The Char Class

- •The String Class

- •The StringBuilder Class

- •VB.NET at Work: The StringReversal Project

- •VB.NET at Work: The CountWords Project

- •Handling Dates

- •The DateTime Class

- •The TimeSpan Class

- •VB.NET at Work: Timing Operations

- •Summary

- •Accessing Folders and Files

- •The Directory Class

- •The File Class

- •The DirectoryInfo Class

- •The FileInfo Class

- •The Path Class

- •VB.NET at Work: The CustomExplorer Project

- •Accessing Files

- •The FileStream Object

- •The StreamWriter Object

- •The StreamReader Object

- •Sending Data to a File

- •The BinaryWriter Object

- •The BinaryReader Object

- •VB.NET at Work: The RecordSave Project

- •The FileSystemWatcher Component

- •Properties

- •Events

- •VB.NET at Work: The FileSystemWatcher Project

- •Summary

- •Displaying Images

- •The Image Object

- •Exchanging Images through the Clipboard

- •Drawing with GDI+

- •The Basic Drawing Objects

- •Drawing Shapes

- •Drawing Methods

- •Gradients

- •Coordinate Transformations

- •Specifying Transformations

- •VB.NET at Work: Plotting Functions

- •Bitmaps

- •Specifying Colors

- •Defining Colors

- •Processing Bitmaps

- •Summary

- •The Printing Objects

- •PrintDocument

- •PrintDialog

- •PageSetupDialog

- •PrintPreviewDialog

- •PrintPreviewControl

- •Printer and Page Properties

- •Page Geometry

- •Printing Examples

- •Printing Tabular Data

- •Printing Plain Text

- •Printing Bitmaps

- •Using the PrintPreviewControl

- •Summary

- •Examining the Advanced Controls

- •How Tree Structures Work

- •The ImageList Control

- •The TreeView Control

- •Adding New Items at Design Time

- •Adding New Items at Runtime

- •Assigning Images to Nodes

- •Scanning the TreeView Control

- •The ListView Control

- •The Columns Collection

- •The ListItem Object

- •The Items Collection

- •The SubItems Collection

- •Summary

- •Types of Errors

- •Design-Time Errors

- •Runtime Errors

- •Logic Errors

- •Exceptions and Structured Exception Handling

- •Studying an Exception

- •Getting a Handle on this Exception

- •Finally (!)

- •Customizing Exception Handling

- •Throwing Your Own Exceptions

- •Debugging

- •Breakpoints

- •Stepping Through

- •The Local and Watch Windows

- •Summary

- •Basic Concepts

- •Recursion in Real Life

- •A Simple Example

- •Recursion by Mistake

- •Scanning Folders Recursively

- •Describing a Recursive Procedure

- •Translating the Description to Code

- •The Stack Mechanism

- •Stack Defined

- •Recursive Programming and the Stack

- •Passing Arguments through the Stack

- •Special Issues in Recursive Programming

- •Knowing When to Use Recursive Programming

- •Summary

- •MDI Applications: The Basics

- •Building an MDI Application

- •Built-In Capabilities of MDI Applications

- •Accessing Child Forms

- •Ending an MDI Application

- •A Scrollable PictureBox

- •Summary

- •What Is a Database?

- •Relational Databases

- •Exploring the Northwind Database

- •Exploring the Pubs Database

- •Understanding Relations

- •The Server Explorer

- •Working with Tables

- •Relationships, Indices, and Constraints

- •Structured Query Language

- •Executing SQL Statements

- •Selection Queries

- •Calculated Fields

- •SQL Joins

- •Action Queries

- •The Query Builder

- •The Query Builder Interface

- •SQL at Work: Calculating Sums

- •SQL at Work: Counting Rows

- •Limiting the Selection

- •Parameterized Queries

- •Calculated Columns

- •Specifying Left, Right, and Inner Joins

- •Stored Procedures

- •Summary

- •How About XML?

- •Creating a DataSet

- •The DataGrid Control

- •Data Binding

- •VB.NET at Work: The ViewEditCustomers Project

- •Binding Complex Controls

- •Programming the DataAdapter Object

- •The Command Objects

- •The Command and DataReader Objects

- •VB.NET at Work: The DataReader Project

- •VB.NET at Work: The StoredProcedure Project

- •Summary

- •The Structure of a DataSet

- •Navigating the Tables of a DataSet

- •Updating DataSets

- •The DataForm Wizard

- •Handling Identity Fields

- •Transactions

- •Performing Update Operations

- •Updating Tables Manually

- •Building and Using Custom DataSets

- •Summary

- •An HTML Primer

- •HTML Code Elements

- •Server-Client Interaction

- •The Structure of HTML Documents

- •URLs and Hyperlinks

- •The Basic HTML Tags

- •Inserting Graphics

- •Tables

- •Forms and Controls

- •Processing Requests on the Server

- •Building a Web Application

- •Interacting with a Web Application

- •Maintaining State

- •The Web Controls

- •The ASP.NET Objects

- •The Page Object

- •The Response Object

- •The Request Object

- •The Server Object

- •Using Cookies

- •Handling Multiple Forms in Web Applications

- •Summary

- •The Data-Bound Web Controls

- •Simple Data Binding

- •Binding to DataSets

- •Is It a Grid, or a Table?

- •Getting Orders on the Web

- •The Forms of the ProductSearch Application

- •Paging Large DataSets

- •Customizing the Appearance of the DataGrid Control

- •Programming the Select Button

- •Summary

- •How to Serve the Web

- •Building a Web Service

- •Consuming the Web Service

- •Maintaining State in Web Services

- •A Data-Driven Web Service

- •Consuming the Products Web Service in VB

- •Summary

1004 Chapter 23 INTRODUCTION TO WEB PROGRAMMING

The Structure of HTML Documents

HTML files are text files that contain text and formatting commands. The commands are strings with a consistent syntax, so that the browser can distinguish them from the text. Every HTML tag appears in a pair of angle brackets (<>). The tag <I> turns on the italic attribute, and the following text is displayed in italics until the </I> tag is found. The statement

HTML is <I>the</I> language of the Web.

will render the following sentence on the browser, without the tags and with the word the in italics:

HTML is the language of the Web.

As I said earlier in the chapter, most tags act upon a portion of the text and appear in pairs. One tag turns on a specific feature, and the other turns it off. The <I> tag is an example, and so are the <B> and <U> tags, which turn on the bold and underline attributes. The tag that turns off an attribute is always preceded by a slash character. To display a segment of text in bold, enclose it with the tags <B> and </B>.

The structure of an HTML document is shown next. If you store the following lines in a text file with the extension HTM and then open it with Internet Explorer, you will see the traditional greeting. Here’s the HTML document:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Your Title Goes Here</TITLE> </HEAD>

<BODY>

Hello, World! </BODY>

</HTML>

To create the most fundamental HTML document, you must start with the <HTML> tag and end with the </HTML> tag. Within these tags should be a HEAD section and a BODY section. The BODY of the document is the portion that is presented within the browser window. The document’s HEAD, marked with the <HEAD> and </HEAD> tags, is where you normally place the following elements:

The document’s title

Information about the document, such as the META and BASE tags

Scripts

The title is the text that appears in the title bar of the browser’s window and is specified with the <TITLE> and </TITLE> tags. META tags don’t display anywhere on the screen but contain useful information regarding the content of the document, such as a description and keywords used by search engines. For example:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Your Title Goes Here</TITLE>

Copyright ©2002 SYBEX, Inc., Alameda, CA |

www.sybex.com |

AN HTML PRIMER 1005

<META NAME=”Keywords”

CONTENT=”health, nutrition, weight control, chronic illness”>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

Hello, World! </BODY>

</HTML>

Attributes

Many HTML tags understand special keywords, which are called attributes. The <BODY> tag, which marks the beginning of the document’s body, for instance, recognizes the BACKGROUND attribute, which lets you specify an image to appear in the document’s background. You can also specify the document’s text color and its background color (if there’s no background image) with the TEXT and BGCOLOR attributes, respectively:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Your Title Goes Here</TITLE> </HEAD>

<BODY BACKGROUND=”paper.jpg” BGCOLOR=”yellow” TEXT=”black”> <H1>Tiled Background</H1>

<P>The background of this page was created with a small image, which is tiled vertically and horizontally by the browser. If the image can’t display, the page will have a solid yellow background. Either way, the text will be black.</P>

</BODY>

</HTML>

Background images start tiling at the top-left corner and work their way across and then down the screen. Many HTML tags accept attribute parameters that position them precisely on the page. Unfortunately, not all browsers understand these elements, so the same page may look perfect in Internet Explorer or Netscape and totally misaligned in another browser. The good news is that you don’t have to learn all these attributes; if you’re working with the Visual Studio IDE, the designer will insert them for you.

URLs and Hyperlinks

The key element in a Web page is the hyperlink, a special instruction embedded in the text that causes the browser to load another page. A hyperlink is a string that appears in different formatting from the rest of the text (usually in a different color and underlined); when the mouse pointer is over a hyperlink, the cursor changes, typically into a finger. When you click the mouse button over a hyperlink, the browser requests and displays another document, which could be on the same or another server.

To connect to another computer and request a document, the hyperlink must contain the name of the computer that hosts the document and the name of the document. Just as each computer on the Internet has a unique name, each document on a computer also has a unique name. Thus, each

Copyright ©2002 SYBEX, Inc., Alameda, CA |

www.sybex.com |

1006 Chapter 23 INTRODUCTION TO WEB PROGRAMMING

document on the World Wide Web has a unique address, which is called a Uniform Resource Locator (URL). The URL for a document is something like the following:

http://www.someserver.com/docName.htm

Note You will notice that some HTML URLs end in htm and some end in html. They are identical; some older operating systems don’t support long extensions, that’s all.

Every piece of information on the World Wide Web has a unique address and can be accessed via its URL. What the browser does depends on the nature of the item. If it’s a Web page (file extension

.html or .htm) or an image (such as a .gif file), the browser displays it. If it’s a sound file (such as a

.wav file), the browser plays it back. Today’s browsers can process many types of documents; older versions can’t. When a browser runs into a document it can’t handle, it asks whether the user wants to download and save the file on disk or open it with an application that the user specifies.

The tag that makes HTML documents come alive is the <A> tag, or anchor tag, which inserts hyperlinks in a document. The <A> and </A> tags enclose one or more words that will be highlighted as hyperlinks. In addition, you must specify the URL of the hyperlink’s destination. For example, the URL of the Sybex home page is:

http://www.sybex.com

The URL to jump to is indicated with the HREF attribute of the <A> tag. To display the string “Visit the SYBEX home page” and to use the word SYBEX as the hyperlink, you enter the following in your document:

Visit the <A HREF=”http://www.sybex.com”>SYBEX</A> home page

This inserts a hyperlink in the document, and each time the user clicks the SYBEX hyperlink, the browser displays the main page at the specified URL.

Note You often need not specify a document name in the hyperlink. Servers are commonly configured to supply the default page, which is known as the home page. The home page is usually the entry to a specific site and contains hyperlinks to other pages making up the site.

To jump directly to a specific page on a Web site, use a hyperlink such as the following:

View a document on <A HREF=”http://www.example.com/HTMLTutorial.htm”>HTML programming</A> on this site.

Most hyperlinks on a typical page jump to other documents that reside on the same server. These hyperlinks usually contain a relative reference to another document on that server. For example, to specify a hyperlink to the document Images.htm that resides in the same folder as the current page, use the following tag:

Click <A HREF=”.\Images.htm”>here</A> to view the images.

The Basic HTML Tags

HTML is certainly easy for a Visual Basic programmer to learn and use. The small part of HTML presented here is all you need to build functional Web pages.

Copyright ©2002 SYBEX, Inc., Alameda, CA |

www.sybex.com |

AN HTML PRIMER 1007

Although you can use the visual tools of the IDE, many times it’s actually simpler to open the HTML file and edit it. The following are the really necessary tags for creating no-frills HTML documents, grouped by category.

Headers

Headers separate sections of a document. Like documents prepared with a word processor, HTML documents can have headers, which are inserted with the <Hn> tag. There are six levels of headers, starting with <H1> (the largest) and ending with <H6> (the smallest). To place a level 1 header in the document, use the tag <H1>:

<H1>Welcome to Our Fabulous Site</H1>

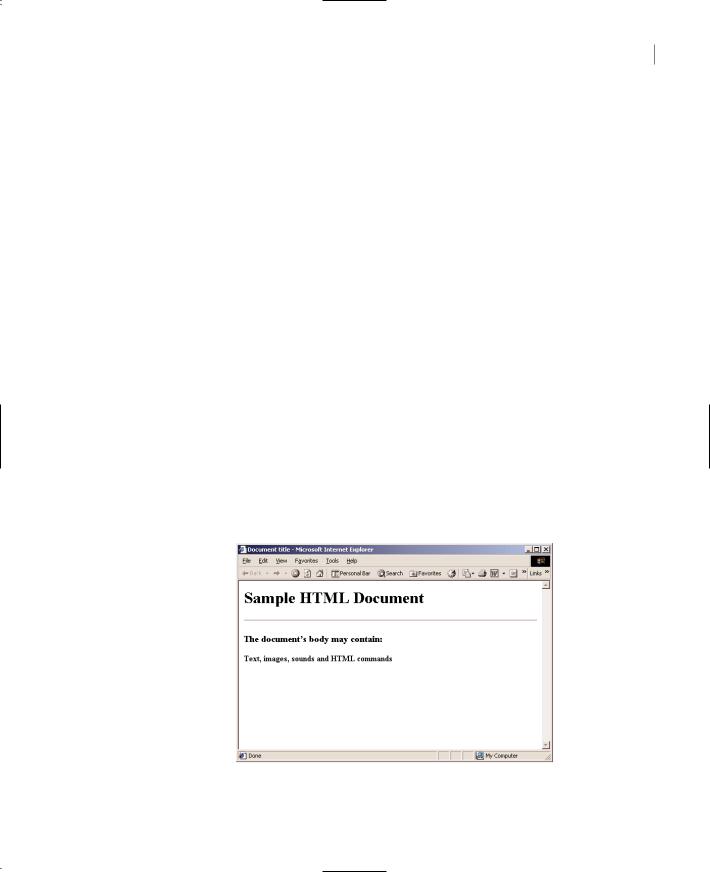

A related tag is the <HR> tag, which displays a horizontal rule and is frequently used to separate sections of a document. The document in Figure 23.1, which demonstrates the HTML tags discussed so far, was produced with the following HTML file:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>

Document title </TITLE>

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H1>Sample HTML Document</H1> <HR>

<H3>The document’s body may contain:</H3> <H4>Text, images, sounds and HTML commands</H4>

</BODY>

</HTML>

Figure 23.1

A simple HTML document with headers and a rule

Copyright ©2002 SYBEX, Inc., Alameda, CA |

www.sybex.com |

1008 Chapter 23 INTRODUCTION TO WEB PROGRAMMING

Paragraph Formatting

HTML won’t break lines into paragraphs whenever you insert a carriage return in the text file. The formatting of the paragraphs is determined by the font(s) used in the document and the size of the browser’s window. To force a new paragraph, you must explicitly tell the browser to insert a carriage return with the <P> tag. The <P> tag also causes the browser to insert additional vertical space. To insert a line break without the additional vertical space, use the <BR> tag.

Character Formatting

HTML provides tags for formatting words and characters. Table 23.1 shows the basic characterformatting tags. The tags listed in pairs can be used alternately for the same effect; <B>…</B> produces the same look as <STRONG>…</STRONG> in most browsers.

Table 23.1: The Basic HTML Character-Formatting Tags

Tag |

What It Does |

<B> or <STRONG> |

Specifies bold text |

<FONT> |

Specifies text characteristics such as typeface, size, and color |

<I> or <EM> |

Specifies italic text (for emphasis) |

<TT> or <CODE> |

Specifies the “typewriter” attribute, so text is displayed in a monospaced font; used |

|

frequently to display computer listings |

|

|

The <FONT> tag specifies the name, size, and color of the font to be used. The <FONT> tag takes one or more of the following attributes:

SIZE Specifies the size of the text in a relative manner. The value of the SIZE argument is not expressed in points, pixels, or any other absolute unit. Instead, it’s a number in the range 1 (the smallest) through 7 (the largest). The following tag displays the text in the smallest possible size:

<FONT SIZE=”1”>tiny type</FONT>

The following tag displays text in the largest possible size:

<FONT SIZE=”7”>HUGE TYPE</FONT>

FACE Specifies the font family. If the specified font does not exist on the client computer, the browser substitutes a similar font. The following tag displays the text between FONT and its matching tag in the Comic Sans MS typeface:

<FONT FACE=”Comic Sans MS”>Some text</FONT>

COLOR Specifies the color of the text.

Tip The XHTML specification recommends, but doesn’t yet require, using external cascading style sheets instead of most formatting tags. (In technical language, tags such as <FONT> are deprecated.) At some point, browsers might not recognize formatting within your HTML document, but you can keep using it during this transition period.

Copyright ©2002 SYBEX, Inc., Alameda, CA |

www.sybex.com |